4.5.3: Quadratic Formula and Complex Sums

- Page ID

- 14435

Complex Roots of Quadratic Functions

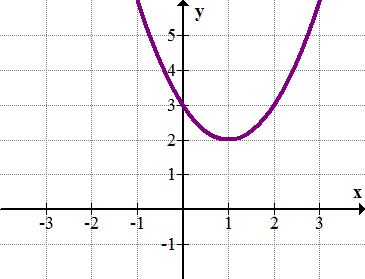

The quadratic function \(\ y=x^{2}-2 x+3\) (shown below) does not intersect the x-axis and therefore has no real roots. What are the complex roots of the function?

Complex Roots of Quadratic Functions

Recall that the imaginary number, \(\ i\), is a number whose square is –1:

\(\ \color{red}i^{2}=-1\) and \(\ \color{red}i=\sqrt{-1}\)

The sum of a real number and an imaginary number is called a complex number. Examples of complex numbers are \(\ 5+4i\) and \(\ 3−2i\). All complex numbers can be written in the form \(\ a+bi\) where \(\ a\) and \(\ b\) are real numbers. Two important points:

- The set of real numbers is a subset of the set of complex numbers where \(\ b=0\).

Examples of real numbers are \(\ 2,7, \frac{1}{2},-4.2\).

- The set of imaginary numbers is a subset of the set of complex numbers where \(\ a=0\).

Examples of imaginary numbers are \(\ i,-4 i, \sqrt{2} i\).

This means that the set of complex numbers includes real numbers, imaginary numbers, and combinations of real and imaginary numbers.

When a quadratic function does not intersect the x-axis, it has complex roots. When solving for the roots of a function algebraically using the quadratic formula, you will end up with a negative under the square root symbol. With your knowledge of complex numbers, you can still state the complex roots of a function just like you would state the real roots of a function.

Let's solve the quadratic equation: m2−2m+5=0

You can use the quadratic formula to solve. For this quadratic equation, \(\ a=1, b=−2, c=5\).

\(\ \begin{aligned}

m &=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a} \\

m &=\frac{-({\color{red}-2}) \pm \sqrt{({\color{red}-2})^{2}-4({\color{red}1})({\color{red}5})}}{2({\color{red}1})} \\

m &=\frac{2 \pm \sqrt{4-20}}{2} \\

m &=\frac{2 \pm \sqrt{-16}}{2} \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad \sqrt{-16}=\sqrt{16} \times i=4 i \\

m &=\frac{2 \pm 4 i}{2} \\

m &=1 \pm 2 i \\

m &=1+2 i \text { or } m=1-2 i

\end{aligned}\)

There are no real solutions to the equation. The solutions to the quadratic equation are \(\ 1+2 i \text { and } 1-2 i\).

Now, let's solve the following equation by rewriting it as a quadratic and using the quadratic formula:

\(\ \frac{3}{e+3}-\frac{2}{e+2}=1\)

To rewrite as a quadratic equation, multiply each term by \(\ (e+3)(e+2)\).

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

\frac{3}{e+3}{\color{red}(e+3)(e+2)}-\frac{2}{e+2}{\color{red}(e+3)(e+2)}=1{\color{red}(e+3)(e+2)} \\

3(e+2)-2(e+3)=(e+3)(e+2)

\end{array}\)

Expand and simplify.

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

3 e+6-2 e-6=e^{2}+2 e+3 e+6 \\

e^{2}+4 e+6=0

\end{array}\)

Solve using the quadratic formula. For this quadratic equation, \(\ a=1, b=4, c=6\).

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

e=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a} \\

e=\frac{-({\color{red}{4}}) \pm \sqrt{({\color{red}4})^{2}-4({\color{red}1})({\color{red}6})}}{2({\color{red}1})} \\

e=\frac{-4 \pm \sqrt{16-24}}{2} \\

e=\frac{-4 \pm \sqrt{-8}}{2} \quad\quad\quad\quad \sqrt{-8}=\sqrt{8} \times i=\sqrt{4 \cdot 2} \times i=2 i \sqrt{2} \\

e=\frac{-4 \pm 2 i \sqrt{2}}{2} \\

e=-2 \pm i \sqrt{2} \\

e=-2+i \sqrt{2} \text { or } e=-2-i \sqrt{2}

\end{array}\)

There are no real solutions to the equation. The solutions to the equation are

\(\ -2+i \sqrt{2} \text { and }-2-i \sqrt{2}\)

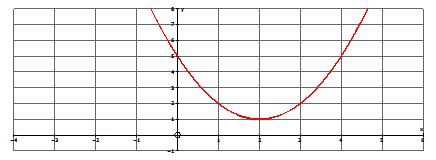

Finally, let's sketch the graph of the following quadratic function. What are the roots of this function?

\(\ y=x^{2}-4 x+5\)

Use your calculator or a table to make a sketch of the function. You should get the following:

As you can see, the quadratic function has no x-intercepts; therefore, the function has no real roots. To find the roots (which will be complex), you must use the quadratic formula.

For this quadratic function, \(\ a=1, b=-4, c=5\).

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a} \\

x=\frac{-({\color{red}-4}) \pm \sqrt{({\color{red}-4})^{2}-4({\color{red}1})({\color{red}5})}}{2({\color{red}1})} \\

x=\frac{4 \pm \sqrt{16-20}}{2} \\

x=\frac{4 \pm \sqrt{-4}}{2} \quad\quad\quad\quad \sqrt{-4}=\sqrt{4} \times i=2 i \\

x=\frac{4 \pm 2 i}{2} \\

x=2 \pm i \\

x=2+i \text { or } x=2-i

\end{array}\)

The complex roots of the quadratic function are \(\ 2+i \text { and } 2-i\).

Examples

Earlier, you were asked to find the complex roots of \(\ y=x^{2}-2 x+3\).

Solution

To find the complex roots of the function \(\ y=x^{2}-2 x+3\), you must use the quadratic formula.

For this quadratic function, \(\ a=1, b=-2, c=3\).

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a} \\

x=\frac{-({\color{red}-2}) \pm \sqrt{({\color{red}-2})^{2}-4({\color{red}1})({\color{red}3})}}{2({\color{red}1})} \\

x=\frac{2 \pm \sqrt{4-12}}{2} \\

x=\frac{2 \pm \sqrt{-8}}{2} \quad\quad\quad \sqrt{-8}=\sqrt{8} \times i=2 \sqrt{2} i \\

x=\frac{2 \pm 2 \sqrt{2} i}{2} \\

x=1 \pm \sqrt{2} i

\end{array}\)

Solve the following quadratic equation. Express all solutions in simplest radical form.

\(\ 2 n^{2}+n=-4\)

Solution

Set the equation equal to zero.

\(\ 2 n^{2}+n+4=0\)

Solve using the quadratic formula.

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a} \\

n=\frac{-({\color{red}1}) \pm \sqrt{({\color{red}1})^{2}-4({\color{red}2})({\color{red}4})}}{2({\color{red}2})} \\

n=\frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{1-32}}{4} \\

n=\frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{-31}}{4} \\

n=\frac{-1 \pm i \sqrt{31}}{4}

\end{array}\)

Solve the following quadratic equation. Express all solutions in simplest radical form.

\(\ m^{2}+(m+1)^{2}+(m+2)^{2}=-1\)

Solution

Expand and simplify.

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

m^{2}+(m+1)(m+1)+(m+2)(m+2)=-1 \\

m^{2}+m^{2}+m+m+1+m^{2}+2 m+2 m+4=-1 \\

3 m^{2}+6 m+5=-1

\end{array}\)

Write the equation in general form.

\(\ 3 m^{2}+6 m+6=0\)

Divide by 3 to simplify the equation.

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

\frac{3 m^{2}}{\color{red}3}+\frac{6 m}{\color{red}3}+\frac{6}{\color{red}3}=\frac{0}{\color{red}3} \\

m^{2}+2 m+2=0

\end{array}\)

Solve using the quadratic formula:

\(\ \begin{array}{l}

m=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a} \\

m=\frac{-({\color{red}2}) \pm \sqrt{({\color{red}2})^{2}-4({\color{red}1})({\color{red}2})}}{2({\color{red}1})} \\

m=\frac{-2 \pm \sqrt{4-8}}{2} \\

m=\frac{-2 \pm \sqrt{-4}}{2} \\

m=\frac{-2 \pm 2 i}{2} \\

m=-1 \pm i

\end{array}\)

Is it possible for a quadratic function to have exactly one complex root?

Solution

No, even in higher degree polynomials, complex roots will always come in pairs. Consider when you use the quadratic formula-- if you have a negative under the square root symbol, both the + version and the - version of the two answers will end up being complex.

Review

- If a quadratic function has 2 x-intercepts, how many complex roots does it have? Explain.

- If a quadratic function has no x-intercepts, how many complex roots does it have? Explain.

- If a quadratic function has 1 x-intercept, how many complex roots does it have? Explain.

- If you want to know whether a function has complex roots, which part of the quadratic formula is it important to focus on?

- You solve a quadratic equation and get 2 complex solutions. How can you check your solutions?

- In general, you can attempt to solve a quadratic equation by graphing, factoring, completing the square, or using the quadratic formula. If a quadratic equation has complex solutions, what methods do you have for solving the equation?

Solve the following quadratic equations. Express all solutions in simplest radical form.

- \(\ x^{2}+x+1=0\)

- \(\ 5 y^{2}-8 y=-6\)

- \(\ 2 m^{2}-12 m+19=0\)

- \(\ -3 x^{2}-2 x=2\)

- \(\ 2 x^{2}+4 x=-11\)

- \(\ -x^{2}+x-23=0\)

- \(\ -3 x^{2}+2 x=14\)

- \(\ x^{2}+5=-x\)

- \(\ \frac{1}{2} d^{2}+4 d=-12\)

Vocabulary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| complex number | A complex number is the sum of a real number and an imaginary number, written in the form \(\ a+bi\). |

| complex root | A complex root is a complex number that, when used as an input (\(\ x\)) value of a function, results in an output (\(\ y\)) value of zero. |

| Imaginary Numbers | An imaginary number is a number that can be written as the product of a real number and i. |

| Quadratic Formula | The quadratic formula states that for any quadratic equation in the form \(\ a x^{2}+b x+c=0, x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a}\). |

| Real Number | A real number is a number that can be plotted on a number line. Real numbers include all rational and irrational numbers. |