1.1: Political Ideas in History

- Page ID

- 1993

Do you believe in government "BY THE PEOPLE, FOR THE PEOPLE, AND OF THE PEOPLE?" Few Americans would say no, especially since these words, spoken by Abraham Lincoln in his 1863 Gettysburg Address, are firmly embedded in the American political system. Yet, governments over the centuries have not always accepted this belief in popularly elected rule.

The American political system is rooted in the ideal that a just government can exist, and that its citizens can experience a good measure of liberty and equality in their personal lives.

Even in the modern United States, many skeptics criticize government as being controlled by greedy, corrupt people who are only interested in lining their own pockets. So, which view is correct? Is government an instrument of its citizens, an entity that represents and protects a beloved country, or an oppressive, self-serving monster that deserves no respect? The Rule of Law implies that government is based on the body of law that is applied equally and fairly, not on the whims of a ruler.

If we look to the past for an answer, we find comments like these:

Behold my sons, with how little wisdom the world is governed. -Axel Oxenstiern (1583-1654)

That government is best which governs least. -Thomas Jefferson

The conflict between the power of the government and the sovereignty of the people is solidly based in the past. Governments are sometimes idealized and often criticized. Yet, virtually every society in history has had some form of government, either as simple as the established leadership of a band of prehistoric people, or as complex as the government of the United States today. We will begin by examining reasons why governments exist and considering some types of government including democracy, particularly as it is practiced in the modern United States.

Laws of Nature and Nature's God

Natural rights are usually seen as opposite of the concept of legal rights. Legal rights are those bestowed onto a person by a given legal system (i.e., rights that can be modified, repealed, and restrained by human laws). Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws, customs, or beliefs of any particular culture or government, and are therefore universal and inalienable (i.e., rights that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws).

Natural rights are closely related to the concept of natural law (or laws). During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to challenge the divine right of kings, and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government (and thus, legal rights) in the form of classical republicanism (built around concepts such as civil society, civic virtue, and mixed government). Conversely, the concept of natural rights is used by others to challenge the legitimacy of all such establishments.

The idea of natural rights is also closely related to that of unalienable rights; some acknowledge no difference between the two, while others choose to keep the terms separate to eliminate association with some features traditionally associated with natural rights. Natural rights, in particular, are considered beyond the authority of any government or international body to dissolve.

The phrase, ."..law of nature and nature's god" is found in the Declaration of Independence.

Divine Right of Kings

The Divine Right of Kings is a political and religious doctrine of royal and political legitimacy. It claims that a monarch is not subject to any earthly authority, that the right to rule is directly given by God. The king is not subject to the will of his people, the aristocracy, or any other earthly power. It implies that only God can judge an unjust king and that any attempt to depose, dethrone, or restrict his powers runs opposite to the will of God.

Social Contract Philosophers

Thomas Hobbes proposed that a society without rules and laws to govern our actions would be a dreadful place to live. Hobbes described a society without rules as living in a “state of nature.” In such a state, people would act on their own accord, without any responsibility to their community. Life in a state of nature would be Darwinian, where the strongest survive and the weak perish. A society, in Hobbes’ state of nature, would be without the comforts and necessities that we take for granted in modern western society. The society would have:

- No place for commerce

- Little or no culture

- No knowledge

- No leisure

- No security and continual fear

- No arts

- Little language

The social contract is unwritten, and is inherited at birth. It dictates that we will not break laws or certain moral codes and, in exchange, we reap the benefits of our society, namely security, survival, education and other necessities needed to live.

In contrast, John Locke viewed men as born into a "perfect state of nature" with certain natural rights and freedoms, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. In Locke's view of the world, men are born good and should be trusted to govern themselves through the creation of laws that protect them from the unjust actions of the government.

Jean Jacques Rousseau went even further in his views, stating, “Man is born free, yet he is in chains everywhere.” He believed that men are shackled with the burdens of oppressive governments, and that it is the duty of men to take control of the government and establish a government responsive to the “general will.” Rousseau’s views are considered closest to the original idea of a direct democracy, as originally practiced in Greece.

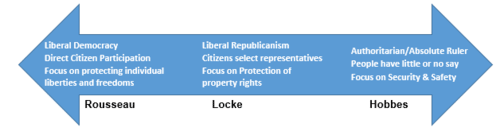

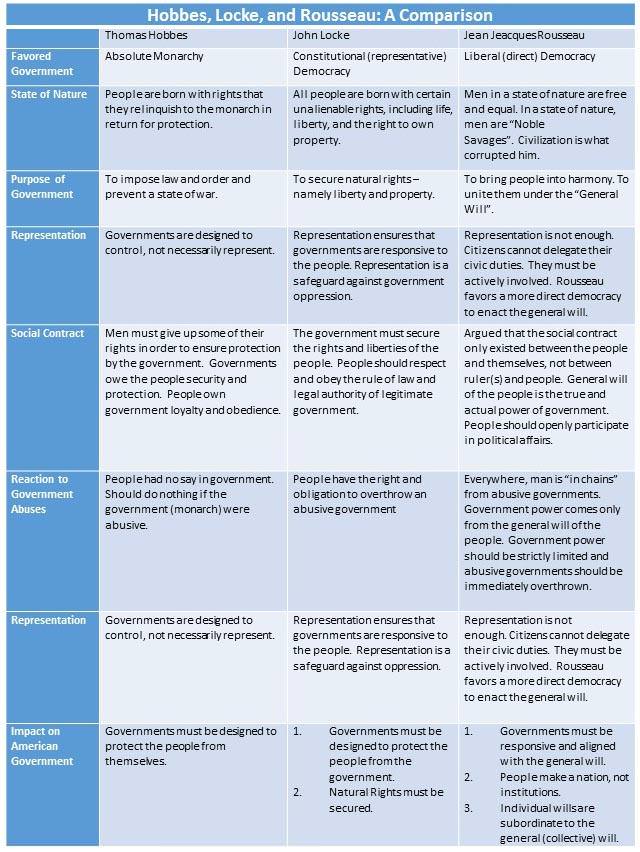

Evaluating the Views of Hobbes, Lock, and Rousseau

The philosophies of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau can be placed along a wide political spectrum involving a trade-off between natural liberties and freedoms versus strong authoritarian governments who provide security and safety in exchange. Hobbes saw the role of government as one involving the provision of security and defense with the people owing everything to a strong and forceful leader. Locke saw the role of government as protecting the individual rights of the people and believed that governments exist only to serve the needs of the people. In Hobbes's view of government, the people should do what the government says in order to stay safe. In Locke's view of government, the people should be in charge of their own government and leaders should do what the people say.

Why Such Different Views?

Why did these men propose such different views of the role of government and its relationship with the people? To understand the answer to this question, we must understand the times in which these men lived.

Thomas Hobbes lived during a period of time when Britain was torn apart by civil war. He believed the king ruled by Divine Right, meaning that the monarch was perceived to be selected by God to rule over the people, and that such a ruler had an absolute and God-given right to be obeyed without question. Others did not share that view and the king was actually beheaded for failing to listen to the will of his people. This tumultuous period of time was known as the English Civil War, and it led to a period of violence and conflict, which would only end with the eventual overthrow of a dictator (Oliver Cromwell) and the return of the monarchy under the rule of William and Mary. To regain their throne, William and Mary had to agree to a limited monarchy in which their power was limited by Parliament and by the people themselves. They were only allowed to return to the throne when they signed the English Bill of Rights.

Locke and Rousseau lived in a period known as the Enlightenment, a time when men began to question the authority of the church and their political rulers. Under men such as Locke and Rousseau, a period of economic and political prosperity began to flourish as advancements were made in science, technology, industry, and global trade. It was truly a time of prosperity and the rise of property ownership by the common man. It is no wonder that Locke was so concerned about the protection of individual rights and property. Prior to the Enlightenment, it would be very unpopular, not to mention unwise, to question the authority of an absolute political ruler such as the king. However, the Enlightenment was a period of open questioning and the application of reason rather than tradition and superstition.

Unlike Locke, Rousseau did not focus singly on the protection of property rights, but upon political liberties. His beliefs were far more radical than Locke’s and, like Locke, are the foundation of much of the Declaration of Independence as well as the United States Bill of Rights.

Social Contracts

While these three philosophers can be placed on a wide political spectrum, they all shared a common belief in one thing: the existence of a "social contract." That is, they believed that there was a real, yet often times unwritten, contract between the government and the people. In Hobbes's view, the people owed everything to the government, and it was the government's job to simply protect people from themselves. The role of the people was to simply do as they were told. In Locke's view, the social contract called for the government to protect the rights and property of individuals. Also, it called for the government to allow the people as many personal freedoms as possible while it was the role of the people to respect the rule of law and to take a strong stand in ensuring that the government did not get out of hand. In Rousseau’s more radical view, governments must submit to the general will of the people, and the people must actively and directly participate in their governance.

The three social contracts of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau have a common understanding that: (1) A social contract exists between government and the people. (2) Social contracts are based on collective action, which means that people work together in order to solve problems and make decisions that affect them as a group. (3) Governments have a specific purpose which is designed to meet the needs, wants, and objectives of the collective group (“the people”). When government provides essential goods and services that would be otherwise economically unavailable or unobtainable to the general public, they are providing public goods. A public good can best be described as a good or service that, once provided, is available to everyone and cannot be excluded from any one group (regardless of how much they have contributed to the cost of providing it). Practical examples of public goods are national defense and public roads.

Comparison of Social Contracts

|

Hobbes |

People collectively agree to give up all their freedom and power to a sovereign (ruler). “That a man be willing, when others are so too, as far forth as for peace and defence of himself he shall think it necessary, to lay down this right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himself. “ Absolute control (authoritarian monarchy) is where all powers and laws are held by that sovereign. Government imposes law and order to prevent the state of war. |

|

Locke |

Governments exist by the consent of the people to protect their natural rights and promote public good. The right of revolution is exercised when the government fails. People may rebel to redress the government. There is the principle of the rule of majority where things are decided by the greater public. (liberal/constitutional monarchy) |

|

Rousseau |

Social contract is made among all people of that society to bring them in harmony. A general will is made by and agreed to by the people who abide by it. “Each of us puts his person and all his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will, and, in our corporate capacity, we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole.” Direct rule by the people. (republicanism/democracy) “Whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be compelled to do so by the whole body.” |

Collective Action Problems: A Practical Example

Goods or services that are provided by the government to the public without charge and that cannot be made exclusive to only one group are called public goods. Public goods come with their own sets of problems. What happens if the social contract is violated, or if one or the other side takes advantage of the social contract for their own benefit? For instance, if the people of a small town vote to construct a new road through the center of their small community, this road would serve the public good because everyone in the community would benefit from its construction and use.

What if only a small number of people actually participated in contributing to the road construction by investing money, time, labor, or materials? Since every shop owner would benefit by the increased traffic and access the road would provide, and everyone would be able to use this road equally regardless of the amount of money, time, labor, or resources they contributed to its construction, this road becomes the best example of a collective action problem. While the road is designed to benefit the entire community, not everyone contributed equally (or even minimally) to its construction and maintenance. Since the road is open for everyone, those who did not contribute to its construction but benefited from its use are called free riders. This “free rider problem” is very common in the study of government and is the most debated part of social contract theory today.

Collective Action Problems in Nations

If we take our example of a road one step further, we can see how collective action problems apply to nations. For example, the United States often contributes troops, materials, weapons, and expertise in addressing foreign problems. When the United States entered the second Iraq war in 2003, it did so with a consortium of other nations. However, as time went on, the number of U.S. allies decreased. Any country that received the benefit of U.S. military action in Iraq and Afghanistan but did not contribute directly to the cost, materials, or personnel involved would be considered a "free rider" because they benefited from the collective action without actually contributing to its cost.

A Further Comparison

Study/Discussion Questions

1. What beliefs did Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau share?

2. How were their beliefs different?

3. What is meant by the terms “natural law” and “social contract”?

4. Explain what each of the philosophers below meant by the quotes attributed to them and how they saw the government’s role in addressing the problems they saw.

|

Quote |

Problem |

Solution |

|

|

Thomas Hobbes |

“Life is solitary, nasty, |

|

|

|

John Locke |

“Men are born with natural rights, including life, liberty and |

||

|

Jean Jacques |

“Man is born free yet |

5. How was the theory of Divine Right used to justify a monarch’s rule?

6. Why were the ideas of Hobbes so different from those of Locke and Rousseau?

7. How did the Enlightenment lead to new ideas in government?

8. How do we see the ideas of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau included in the American system of government?

9. What is a public good? Provide an example.

10. What are free riders and why are they a problem with regard to collective actions?

11. Benjamin Franklin once said, “Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety .”What does Franklin's quote mean and how does it relate to our discussion of the social contract? Which of the social contract philosophers would most agree with this statement? Which would be least likely to agree? Why?