6.1: Processes Used to Affect Public Policy

- Page ID

- 2011

Public opinion is one of the most frequently used terms in American politics. At the most basic level, public opinion represents people’s collective preferences on matters related to government and politics. However, public opinion is a complex phenomenon, and scholars have developed a variety of interpretations of what public opinion means. One perspective holds that individual opinions matter; therefore, the opinions of the majority should be weighed more heavily than opinions of the minority when leaders make decisions. A contrasting view maintains that public opinion is controlled by organized groups, government leaders, and media elites. The opinions of those in positions of power or who have access to those in power carry the most weight.

Public opinion is often made concrete through questions asked on polls. Politicians routinely cite public opinion polls to justify their support of or opposition to public policies. Candidates use public opinion strategically to establish themselves as front-runners or underdogs in campaigns. Interest groups and political parties use public opinion polls to promote their causes. The mass media incorporate reports of public opinion into news stories about government and politics.

What is Public Opinion?

Scholars do not agree on a single definition of public opinion. The concept means different things depending on how one defines “the public” and assumptions about whose opinion should or does count the most—individuals, groups, or elites.

Most simply, the public can be thought of as people who share something in common, such as a connection to a government and a society that is confronted by particular issues that form the bases of public policies. Not all people have the same connection to issues. Some people are part of the attentive public who pay close attention to government and politics in general. Other individuals are members of issue publics who focus on particular public policy debates, such as abortion, or defense spending, and ignore others. They may focus on a policy that has personal relevance. A healthcare activist, for example, may have a close relative or friend who suffers from a prolonged medical problem. Some members of the public have little interest in politics or issues, and their interests may not be represented.

An opinion is the position—favorable, unfavorable, neutral, or undecided—people take on a particular issue, policy, action, or leader. Opinions are not facts; they are expressions of people’s feelings about a specific political object. Pollsters seeking people’s opinions often say to respondents as they administer a survey, “there are no right or wrong answers; it’s your thoughts that count.” Opinions are related to but not the same as attitudes, or persistent, general orientations toward people, groups, or institutions. Attitudes often shape opinions. For example, people who hold attitudes strongly in favor of racial equality support public policies designed to limit discrimination in housing and employment.

Public opinion can be defined most generically as the sum of many individual opinions. More specific notions of public opinion place greater weight on individual, majority, group, or elite opinion when considering policy decisions.

Video: Constructing Public Opinion

Equality of Individual Opinions

Public opinion can be viewed as the collection of individual opinions, where all opinions deserve equal treatment regardless of whether the individuals expressing them are knowledgeable about an issue or not. Thus, public opinion is the aggregation of preferences of people from all segments of society. The use of public opinion polls to gauge what people are thinking underlies this view. By asking questions of a sample of people who are representative of the U.S. population, pollsters contend they can assess the American public’s mood. People who favor this perspective on public opinion believe that government officials should take into account both majority and minority views when making policy.

Another perspective maintains that public opinion is the opinion held by most people on an issue. In a democracy, the opinions of the majority are the ones that should count the most and should guide government leaders’ decision making. The opinions of the minority are less important than those of the majority. This view of public opinion is consistent with the idea of popular election in that every citizen is entitled to an opinion—in essence, a vote—on a particular issue, policy, or leader. In the end, the position that is taken by the most people—in other words, the position that receives the most votes—is the one that should be adopted by policymakers.

Majority Opinion

Rarely, if ever, does the public hold a single unified opinion. There is often significant disagreement in the public’s preferences, and clear majority opinions do not emerge. This situation poses a challenge for leaders looking to translate these preferences into policies. In 2005, Congress was wrestling with the issue of providing funding for stem cell research to seek new medical cures. Opinion polls indicated that a majority of the public (56 percent) favored stem cell research. However, views differed markedly among particular groups who formed important political constituencies for members. White evangelical Protestants opposed stem cell research (58 percent), arguing the need to protect human embryos, while mainline Protestants (69 percent) and Catholics supported research (63 percent).

How Individuals Affect Public Policy

Public policy is a complex and many-layered process. It involves the interplay of many parties such as business, interest groups, and individuals as they all compete and collaborate to influence policymakers to act in a particular way and on a variety of policies.

These individuals use numerous tactics to advance their interests. The tactics can include lobbying, advocating their positions publicly, attempting to educate supporters and opponents, and mobilizing allies on a particular issue. Most often policy outcomes involve compromises among interested parties.

Public opinion and individual priorities have a strong influence on public policy over time. A citizen may choose to become involved in politics by voting, campaigning, contributing to campaigns, demonstrating, or writing to elected officials. These actions influence public policy through electoral politics, citizen rallies, and actions that affect governmental decision makers.

How Groups Affect Public Policy

Groups work hard to frame issue debates to their advantage. They often will gauge public preferences and use this information when devising media tactics to gain support for their positions. Opposing groups will present competing public opinion poll data in an effort to influence decision-makers and the press. In 1997, the United States’ participation in a summit in Kyoto, Japan, where nations signed a climate-control treaty, sparked a barrage of media stories on the issue of global warming and the potential for deadly gasses to induce climate change. Most Americans believed then that global warming existed and that steps should be taken to combat the problem. Groups such as the Environmental Defense Fund, Greenpeace, and the Sierra Club who favor government-imposed regulations on fossil-fuel companies and automobile manufacturers to curb pollution cited opinion poll data showing that over 70 percent of the public agreed with these actions.

Organizations representing industry interests, such as the now-defunct Global Climate Coalition, used opinion polls indicating that the public was reluctant to sacrifice jobs or curb their personal energy use to stop global warming. The debate in the media among competing groups influenced public opinion over the following decade. There was a massive shift in opinion, as only 52 percent believed that global warming was a problem in 2010. Social media facilitate people’s ability to express their opinions through groups, such as those related to environmental activism.

Political Parties and Public Opinion

Typically, a political party is a political organization seeking to influence government policy by nominating its own select candidates to hold seats in political office, via the process of electoral campaigning. Parties often promote a certain vision that is supported by a written platform with specific goals that form a coalition among disparate interests.

The type of electoral system is a major factor in determining the type of party political system. In countries with a simple plurality voting system, there can be as few as two parties elected in any given jurisdiction. In countries that have a proportional representation voting system, as exists throughout Europe, or a preferential voting system, such as in Australia or Ireland, three or more parties are often elected to parliament in significant proportions, allowing more access to public office. In a nonpartisan system, no official political parties exist, sometimes due to legal restrictions on political parties. In nonpartisan elections, each candidate is eligible for office on his or her own merits. In nonpartisan legislatures, no formal party alignments within the legislature are common.

Most likely, the party that is not in power, criticizes the policies and beliefs of the party that is in power in an attempt to sway public opinion and to garner support for their candidate or platform.

Video: Social Media and Public Opinion on Politics

Video Comprehension Check

After watching the above video, answer the following questions.

- How does social media differ from mass media?

- Why are many politicians utilizing social media rather than mass media?

- Which do you think has more influence in your life - mass media or social media?

- Does social media "trap" people into following the majority rather than voting with their own political beliefs? Explain your answer.

Politicians, pollsters, policy specialists, activists, and journalists have assumed the position of opinion leaders who shape, create, and interpret public opinion. These political elites are devoted to following public affairs—it’s their job. Noted journalist and social commentator Walter Lippmann observed that average people have neither the time nor the inclination to handle the impossible task of keeping up with the myriad issues that confront the nation. They do not have the opportunity to directly experience most political events and must rely on second-hand accounts conveyed by elites primarily through mass media. In Lippmann’s view, public opinion is best managed by specialists who have the knowledge and capabilities to promote policies. Thus, elite opinion, and not the views of average citizens, should count the most.

The mass media rely heavily on the opinions of government elites, especially when covering foreign policy and domestic issues, such as the economy and employment. The breadth of news coverage about foreign affairs is constrained to reflect the range of viewpoints expressed by officials such as members of Congress who are debating the issues. The voices of average Americans are much less prominent in news coverage. As political scientist V. O. Key stated, “The voice of the people is but an echo.”

Elite opinion is increasingly articulated by pundits who offer their opinion or commentary on political issues. College professors, business and labor leaders, lobbyists, public relations representatives, and pollsters are typical pundits who provide expert opinions. Some pundits represent distinctly partisan or ideological viewpoints and use public opinion data selectively to support these positions. Pundits can establish their credentials as experts on governmental affairs and politics through their frequent media appearances as “talking heads” on cable television programs such as CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News.

The Media and The Presidency

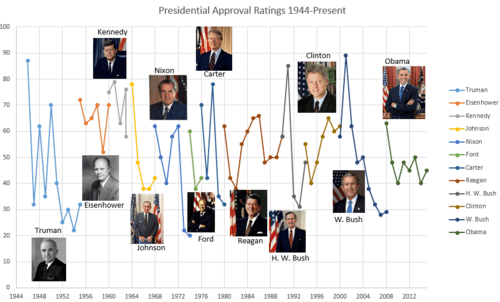

For over fifty years, pollsters have asked survey respondents, “Do you approve or disapprove of the way that the president is handling his job?” Over time there has been variation from one president to the next, but the general pattern is unmistakable. Approval starts out fairly high (near the percentage of the popular vote), increases slightly during the honeymoon, fades over the term, and then levels off. Presidents differ largely in the rate at which their approval rating declines. President Kennedy’s support eroded only slightly, as opposed to the devastating drops experienced by Ford and Carter. Presidents in their first terms are well aware that, if they fall below 50 percent, they are in danger of losing re-election or of losing allies in Congress in the midterm elections.

Events during a president’s term—and how the news media frame them—drive approval ratings up or down. Depictions of economic hard times, drawn-out military engagements (e.g., Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq), unpopular decisions (e.g., Ford’s pardon of Nixon), and other bad news drag approval ratings lower. The main upward push comes from quick international interventions, as for President Obama after the killing of Osama bin Laden in 2011, or successfully addressing national emergencies, which boost a president’s approval for several months. Under such conditions, official Washington speaks more in one voice than usual, the media drop their criticism as a result, and presidents depict themselves as embodiments of a united America.

The successful war against Iraq in 1991 pushed approval ratings for the elder Bush to 90 percent, exceeded only by the ratings of his son after 9/11. It may be beside the point whether the president’s decision was smart or a blunder. Kennedy’s press secretary, Pierre Salinger, later recalled how the president’s approval ratings actually climbed after Kennedy backed a failed invasion by Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs: “He called me into his office and he said, ‘Did you see that Gallup poll today?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Do you think I have to continue doing stupid things like that to remain popular with the American people?’”

But as a crisis subsides, so too does official unity, tributes in the press, and the president’s lofty approval ratings. Short-term effects wane over the course of time. Bush’s huge boost from 9/11 lasted well into early 2003; he got a smaller, shorter lift from the invasion of Iraq in April 2003 and another from the capture of Saddam Hussein in December before dropping to levels -perilously near, then below, 50 percent. Narrowly re-elected in 2008, Bush saw his approval sink to new lows (around 30 percent) over the course of his second term.

The public’s approval of the president fluctuates wildly over time depending upon such factors as the economy, national security, and other events that take place during the presidential term.

|

INTERPRETING CHARTS: |

|

Using the chart above, respond to the following questions 1. In most cases, when do presidents see the highest levels of public approval? 2. When do presidents often see the lowest levels of public approval? 3. What historical events most likely impacted each the following presidents? What impact can be seen in the chart? Truman: Eisenhower: Johnson: Nixon: Gerald Ford: Jimmy Carter: Ronald Reagan: H. W. Bush: Bill Clinton: W. Bush: Barack Obama: *Donald Trump: use the link Real Clear Politics - Latest Polls for President Trump 4. What factors can you think of that would cause a “rally effect” in the polls? What factors can you think of that would cause a great drop in approval ratings? Give examples from the chart for each. |

Naturally and inevitably, presidents employ pollsters to measure public opinion. Poll data can influence presidents’ behavior, the calculation, and presentation of their decisions and policies, and their rhetoric.

After the devastating loss of Congress to the Republicans midway through his first term, President Clinton hired public relations consultant Dick Morris to find widely popular issues on which he could take a stand. Morris used a “60 percent rule”: if six out of ten Americans were in favor of something, Clinton had to be too. Thus the Clinton White House crafted and adopted some policies knowing that they had broad popular support, such as balancing the budget and “reforming” welfare.

Even when public opinion data has no effects on a presidential decision, it can still be used to ascertain the best way to justify the policy or to find out how to present (i.e., spin) unpopular policies so that they become more acceptable to the public. Polls can identify the words and phrases that best sell policies to people. President George W. Bush referred to “school choice” instead of “school voucher programs,” to the “death tax” instead of “inheritance taxes,” and to “wealth-generating private accounts” rather than “the privatization of Social Security.” He presented reducing taxes for wealthy Americans as a “jobs” package.

Polls can even be used to adjust a president’s personal behavior. After a poll showed that some people did not believe that President Obama was a Christian, he attended services, with photographers in tow, at a prominent church in Washington, D.C.

|

Presidential Polling Data |

|

For current polling data from a variety of sources, go to Real Clear Politics |

Presidents speak for various reasons: to represent the country, address issues, promote policies, and seek legislative accomplishments; to raise funds for their campaign, their party, and its candidates; and to berate the opposition. They also speak to control the executive branch by publicizing their thematic focus, ushering along appointments, and issuing executive orders. They aim their speeches at those physically present and, often, at the far larger audience reached through the media.

In their speeches, presidents celebrate, express national emotion, educate, advocate, persuade, and attack. Their speeches vary in importance, subject, and venue. They give major ones, such as the inauguration and State of the Union. They memorialize events such as 9/11 and speak at the site of tragedies (as President Obama did on January 12, 2011, in Tucson, Arizona, after the shootings of Rep. Gabrielle Giffords and bystanders by a crazed gunman). They give commencement addresses. They speak at party rallies. And they make numerous routine remarks and brief statements. Presidents are more or less engaged in composing and editing their speeches. For speeches that articulate policies, the contents will usually be considered in advance by the people in the relevant executive branch departments and agencies who make suggestions and try to resolve or meld conflicting views, for example, on foreign policy by the State and Defense departments, the CIA, and National Security Council. It will be up to the president, to buy in on, modify, or reject themes, arguments, and language.

The president’s speechwriters are involved in the organization and contents of the speech. They contribute memorable phrases, jokes, applause lines, transitions, repetition, rhythm, emphases, and places to pause. They write for ease of delivery, the cadence of the president’s voice, mannerisms of expression, idioms, pace, and timing.

In search of friendly audiences, congenial news media, and vivid backdrops, presidents often travel outside Washington to give their speeches. In his first 100 days in office in 2001, George W. Bush visited 26 states to give speeches; this was a new record even though he refused to spend a night anywhere other than in his own beds at the White House, at Camp David (the presidential retreat), or on his Texas ranch.

Memorable settings may be chosen as backdrops for speeches, but they can backfire. On May 1, 2003, President Bush emerged from a plane that just landed on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln and spoke in front of a huge banner that proclaimed “Mission Accomplished,” implying the end of major combat operations in Iraq. The banner was positioned for the television cameras to ensure that the open sea, not San Diego, appeared in the background. The slogan may have originated with the ship’s commander or sailors, but the Bush people designed and placed it perfectly for the cameras and choreographed the scene.

Speechmaking can entail "going public" where presidents give a major address to promote public approval of their decisions, to advance their policy objectives and solutions in Congress and the bureaucracy, or to defend themselves against accusations of illegality and immorality. Going public is “a strategic adaptation to the information age.”

According to a study of presidents’ television addresses, they fail to increase public approval of the president and rarely increase public support for the policy action the president advocates. There can be a rally phenomenon where people are motivated around an event or action of the president that sees a rapid rise in public approval (such as the first Iraq War and the response to the September 11 attacks in 2001). The president’s approval rating rises during periods of international tension and likely use of American force. Even at a time of policy failure, the president can frame the issue and lead public opinion. Crisis news coverage likely supports the president.

Moreover, nowadays, presidents, while still going public—that is, appealing to national audiences—increasingly go local: they take a targeted approach to influencing public opinion. They go for audiences who might be persuadable, such as their party base and interest groups, and to strategically chosen locations.

Public Opinion Polling

Public opinion polling is prevalent even outside election season. Are politicians and leaders listening to these polls, or is there some other reason for them? Some believe the increased collection of public opinion is due to the growing support of delegate representation. The theory of delegate representation assumes the politician is in office to be the voice of the people.

If voters want the legislator to vote for legalizing marijuana, for example, the legislator should vote to legalize marijuana. Legislators or candidates who believe in delegate representation may poll the public before an important vote comes up for debate in order to learn what the public desires them to do.

Others believe polling has increased because politicians, like the president, operate in permanent campaign mode. To continue contributing money, supporters must remain happy and convinced the politician is listening to them. Even if the elected official does not act in a manner consistent with the polls, he or she can mollify everyone by explaining the reasons behind the vote.

Regardless of why the polls are taken, studies have not clearly shown whether the branches of government consistently act on them. Some branches appear to pay closer attention to public opinion than other branches, but events, time periods, and politics may change the way an individual or a branch of government ultimately reacts.

Public Opinion and Elections

Elections are the events on which opinion polls have the greatest measured effect. Public opinion polls do more than show how we feel on issues or project who might win an election. The media use public opinion polls to decide which candidates are ahead of the others and therefore of interest to voters and worthy of interview. From the moment President Obama was inaugurated for his second term, speculation began about who would run in the 2016 presidential election. Within a year, potential candidates were being ranked and compared by a number of newspapers.

The speculation included favorability polls on Hillary Clinton, which measured how positively voters felt about her as a candidate. The media deemed these polls important because they showed Clinton as the frontrunner for the Democrats in the next election.

During the presidential primary season, we see examples of the bandwagon effect, in which the media pays more attention to candidates who poll well during the fall and the first few primaries. Bill Clinton was nicknamed the “Comeback Kid” in 1992 after he placed second in the New Hampshire primary despite accusations of adultery with Gennifer Flowers. The media’s attention on Clinton gave him the momentum to make it through the rest of the primary season, ultimately winning the Democratic nomination and the presidency.

Polling is also at the heart of horserace coverage. Just like an announcer at the racetrack, the media calls out every candidate’s move throughout the presidential campaign. Horserace coverage can be neutral, positive, or negative, depending upon what polls or facts are covered. During the 2012 presidential election, the Pew Research Center found that both Mitt Romney and President Obama received more negative than positive horserace coverage, with Romney’s growing more negative as he fell in the polls.

Horserace coverage is often criticized for its lack of depth; the stories skip over the candidates’ issue positions, voting histories, and other facts that would help voters make an informed decision. Yet, horserace coverage is popular because the public is always interested in who will win, and it often makes up a third or more of news stories about the election.

Exit polls, taken the day of the election, are the last election polls conducted by the media. Announced results of these surveys can deter voters from going to the polls if they believe the election has already been decided.

Exit polling seems simple. An interviewer stands at a polling place on Election Day and asks people how they voted. But the reality is different. Pollsters must select sites and voters carefully to ensure a representative and random poll. Some people refuse to talk and others may lie. The demographics of the polled population may lean more towards one party than another.

Studies suggest that exit polls can affect voter turnout. Reports of close races may bring additional voters to the polls, whereas apparent landslides may prompt people to stay home. Other studies note that almost anything, including bad weather and lines at polling places, dissuades voters. Ultimately, it appears exit poll reporting affects turnout by up to 5 percent.

On the other hand, limiting exit poll results means major media outlets lose out on the chance to share their carefully collected data, leaving small media outlets able to provide less accurate, more impressionistic results. And few states are affected anyway since the media invest only in those where the election is close. Finally, an increasing number of voters are now voting up to two weeks early, and these numbers are updated daily without controversy.

Public opinion polls also affect how much money candidates receive in campaign donations. Donors assume public opinion polls are accurate enough to determine who the top two to three primary candidates will be, and they give money to those who do well. Candidates who poll at the bottom will have a hard time collecting donations, increasing the odds that they will continue to do poorly.

Presidents running for reelection also must perform well in public opinion polls, and being in office may not provide an automatic advantage. Americans often think about both the future and the past when they decide which candidate to support.

They have three years of past information about the sitting president, so they can better predict what will happen if the incumbent is reelected. That makes it difficult for the president to mislead the electorate. Voters also want a future that is prosperous. Not only should the economy look good, but citizens want to know they will do well in that economy.

For this reason, daily public approval polls sometimes act as both a referendum of the president and a predictor of success.

Public Opinion and Government

Individually, of course, politicians cannot predict what will happen in the future or who will oppose them in the next few elections. They can look to see where the public is in agreement as a body. If public mood changes, the politicians may change positions to match the public mood. The more savvy politicians look carefully to recognize when shifts occur. When the public is more or less liberal, the politicians may make slight adjustments to their behavior to match. Politicians who frequently seek to win office, like House members, will pay attention to the long- and short-term changes in opinion. By doing this, they will be less likely to lose on Election Day.

If presidents have enough public support, they use their level of public approval indirectly as a way to get their agenda passed. Immediately following Inauguration Day, for example, the president enjoys the highest level of public support for implementing campaign promises. This is especially true if the president has a mandate, which is more than half the popular vote. Barack Obama’s recent 2008 victory was a mandate with 52.9 percent of the popular vote and 67.8 percent of the Electoral College vote.

When presidents have high levels of public approval, they are likely to act quickly and try to accomplish personal policy goals. They can use their position and power to focus media attention on an issue. Modern presidents may find more success in using their popularity to increase media and social media attention on an issue. Even if the president is not the reason for congressional action, he or she can cause the attention that leads to change.

In some instances, presidents may appear to directly consider public opinion before acting or making decisions. However, further examples show that presidents do not consistently listen to public opinion.

While presidents have at most only two terms to serve and work, members of Congress can serve as long as the public returns them to office. We might think that for this reason public opinion is important to representatives and senators, and that their behavior, such as their votes on domestic programs or funding, will change to match the expectation of the public. In a more liberal time, the public may expect to see more social programs. In a non-liberal time, the public mood may favor austerity, or decreased government spending on programs. Failure to recognize shifts in public opinion may lead to a politician’s losing the next election.

House of Representatives members, with a two-year term, have a more difficult time recovering from decisions that anger local voters. And because most representatives continually fundraise, unpopular decisions can hurt their campaign donations. For these reasons, it seems representatives should be susceptible to polling pressure.

The Senate is quite different from the House. Senators do not enjoy the same benefits of incumbency, and they win reelection at lower rates than House members. Yet, they do have one advantage over their colleagues in the House: senators hold six-year terms, which gives them time to engage in fence-mending to repair the damage from unpopular decisions. In the Senate, Stimson’s study confirmed that opinion affects a senator’s chances at re-election, even though it did not affect House members. Specifically, the study shows that when public opinion shifts, fewer senators win re-election. Thus, when the public as a whole becomes more or less liberal, new senators are elected. Rather than the senators shifting their policy preferences and voting differently, it is the new senators who change the policy direction of the Senate.

Beyond voter polls, congressional representatives are also very interested in polls that reveal the wishes of interest groups and businesses. If AARP, one of the largest and most active groups of voters in the United States, is unhappy with a bill, members of the relevant congressional committees will take that response into consideration. If the pharmaceutical or oil industry is unhappy with a new patent or tax policy, its members’ opinions will have some effect on representatives’ decisions, since these industries contribute heavily to election campaigns.

There is some disagreement about whether the Supreme Court follows public opinion or shapes it. The lifetime tenure the justices enjoy was designed to remove everyday politics from their decisions, protect them from swings in political partisanship, and allow them to choose whether and when to listen to public opinion. More often than not, the public is unaware of the Supreme Court’s decisions and opinions. When the justices accept controversial cases, the media tune in and ask questions, raising public awareness and affecting opinion. But do the justices pay attention to the polls when they make decisions?

Studies that look at the connection between the Supreme Court and public opinion are contradictory. Early on, it was believed that justices were like other citizens: individuals with attitudes and beliefs who would be affected by political shifts.

Other studies have revealed a more complex relationship between public opinion and judicial decisions, largely due to the difficulty of measuring where the effect can be seen. Some studies look at the number of reversals taken by the Supreme Court, which are decisions with which the Court overturns the decision of a lower court. In one study, the authors found that public opinion slightly affects cases accepted by the justices. Whether the case or court is currently in the news may also matter. A study found that if the majority of Americans agree on a policy or issue before the court, the court’s decision is likely to agree with public opinion.

Study/Discussion Questions

1. Have you ever participated in an opinion poll? Did you feel that you were able to adequately convey your feelings about the issues you were asked about?

2. What are the different ideas about what public opinion really is? What might the advantages of looking at public opinion in each of those different ways be?

3. What is the difference between an attitude and an opinion?

4. What drives presidential approval ratings?

5. What role does a president's television address play in presidential approval ratings?

Sources:

[1] James A. Stimson, Public Opinion in America, 2nd ed. (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1999).

[2] Carroll J. Glynn, Susan Herbst, Garrett J. O’Keefe, and Robert Y. Shapiro, Public Opinion (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1999).

[3] Susan Herbst, Numbered V