5.2: II. Identifying Student Resources

- Page ID

- 15143

39

II. Identifying Student Resources

Emily van Zee and Elizabeth Gire

You already know a lot about the Sun, Moon, and the stars from everyday experiences being outside and going to school. You also likely have absorbed information informally from songs, newspapers, books, and the Internet. These are resources on which to build a deeper understanding through systematic explorations in this class.

A. Documenting initial knowledge about the Sun, Moon, and stars

Question 5.1 What do you already know about the Sun, Moon, and stars?

Document your initial knowledge about the Sun, Moon, and stars by responding to the following diagnostic questions. Your responses will not be graded. You will answer the same questions again near the end of the unit, compare initial and current responses, and write a reflection about changes in your understandings and about the ways these occurred.

Name_____________________________ Date___________

Diagnostic Questions about the Sun, Moon, and Stars

Why does it get dark at night?

Why is it cold in the winter and hot in the summer?

Why does the moon seem to have different shapes at different times?

What do you already know about the Sun?

What questions do you have about the Sun?

What do you already know about the Moon?

What questions do you have about the Moon?

What do you already know about the stars?

What questions do you have about the stars?

Diagnostic Questions: Science & Science Learning

How would you define a “scientific explanation”?

How would you define “inquiry approaches to learning and teaching”?

To what extent are you interested in learning science?

Not interested in 1 2 3 4 5 Interested in

learning science learning science

Comment:

To what extent are you interested in teaching science?

Not interested in 1 2 3 4 5 Interested in

teaching science teaching science

Comment:

B. Noticing the sky

The key to learning about the sky is to look up whenever outside! Frequently! You can draw on resources from your own experiences, from those interpreted in cultural stories, art, and poetry, and from observations you and companions make, even young children, when noticing and talking about the Moon.

- Talk with your group members about some of your experiences in watching a sunrise or sunset, seeing the Moon, and/or noticing the stars.

- What did you learn from these experiences?

- How might you increase how often you notice the sky during this course?

Story-tellers from many cultures as well as artists and poets have offered intriguing interpretations of what they were seeing.

1. The Sun, Moon, and stars as represented in cultural stories

People from many cultures around the world have told stories about the Sun, Moon, and stars (see: http://solar-center.stanford.edu/folklore/Solar-Folklore.pdf). They have observed and pondered changes in where the Sun seems to rise and set, how high the Sun seems to arc across the sky, and how long daylight or darkness lasts. They also have wondered why the Moon seems to change its shape as well as when and where one sees the Moon with respect to the Sun. Also puzzling has been why the stars seem to be arranged the way they are and how they seem to move. People all over the Earth have watched and wondered about such questions (https://www.lpi.usra.edu/planetary_news/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Multicultural_Astronomy_2013_v7.1.pdf ).

People also have “seen” a variety of creatures residing on the full Moon. These have included a human face, a man collecting firewood, a woman and child, a rabbit, a princess, a toad and a tree (see: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/07/the-man-in-the-moon-or-the-rabbit-or-toad-or-or-or/563450/ ).

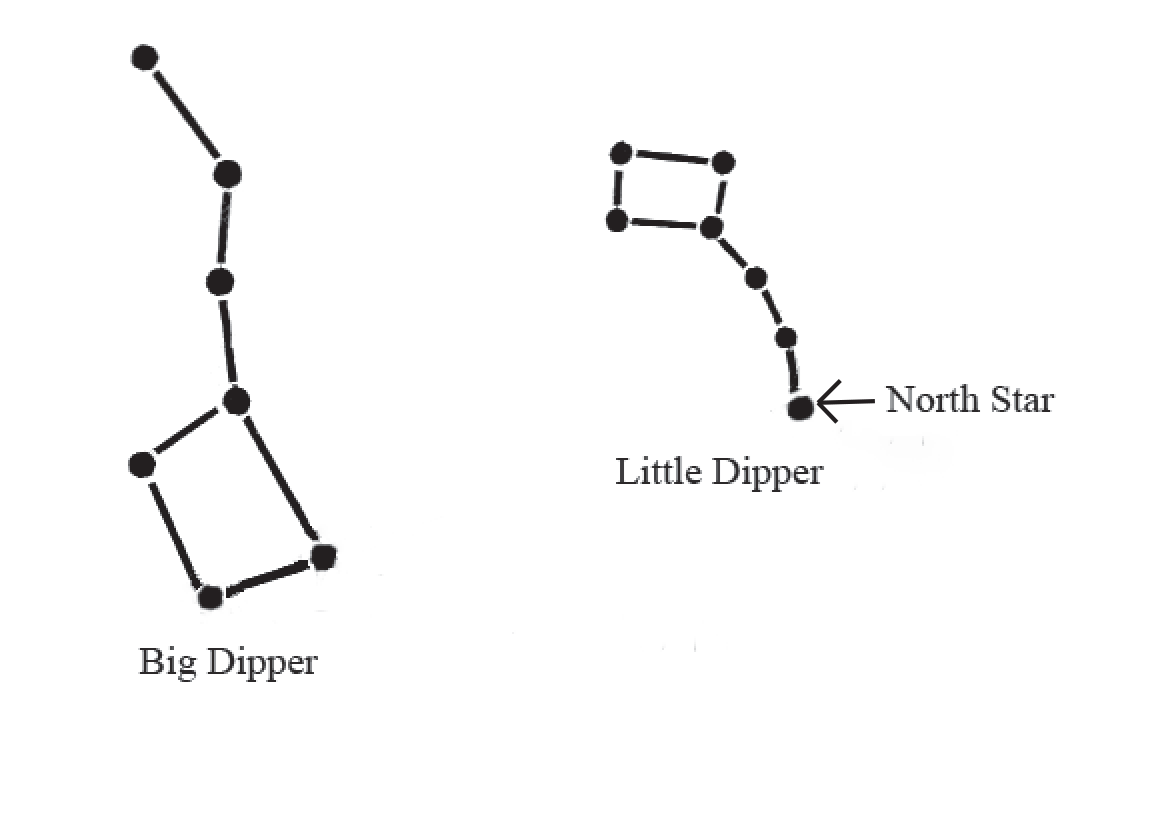

In addition, people have envisioned many objects and creatures outlined by the stars (See: https://www.aavso.org/sites/default/files/education/vsa/Chapter3.pdf). Where we live in the northern hemisphere, for example, stars that seem to outline the shape of ladles, the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper, are often visible even in a city sky. As shown in Fig. 5.1, two stars forming part of the cup of the Big Dipper seem to point to a star at the end of the handle in the Little Dipper. This star, known as the North Star, does not seem to move whereas other stars seem to revolve around it during the night.

The stars forming the dippers are contained within the constellations known as Ursa Major (Great Bear) and Ursa Minor (Little Bear) as shown in Fig. 5.2. Ursa is the Latin word for bear. People of many cultures have associated various animals with these visual patterns of stars and told stories about them (see: https://www.constellation-guide.com/constellation-list/ursa-major-constellation/ ).

The North Star also is called Polaris, from the Latin Stella Polaris or Pole Star (https://www.lpi.usra.edu/education/skytellers/polaris/). As seen from Earth, this star lies almost directly above the Earth’s north pole and appears to be motionless as the other stars seem to revolve around it during the night.

The big star in the tail of Maang represents Giwedin’anung, a star around which the other constellations appear to revolve. The Ojibwe constellations shown in the Ojibwe Sky Star Map are superimposed on constellations based on myths from ancient Greek and Roman times such as those shown in Fig. 5.3.

If you live in the northern hemisphere, on a clear night see if you can find the Big Dipper, Little Dipper and the North Star. Can you also see Ursa Major, follow this Great Bear’s pointer stars to Polaris, and recognize the Little Bear, Ursa Minor? If you can watch for several hours, you can see the other stars appear to revolve around a star that seems to be motionless as shown in Fig. 5.4.

If you live in the southern hemisphere, there is no star in the sky that seems motionless during the night. You can infer where such a point would be, however, by using two bright stars to envision the location of the third apex of an equilateral triangle as shown in https://centralaustralianbushwalkers.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/skymap-south-by-stars-pdf.jpg. You can see the apparent motion of constellations around a point in the sky if you can watch over several hours. On a clear night, also see if you can find the Southern Cross, Centaurus the Centaur with Alpha Centauri, a star system just 4.37 light years away as well as Omega Centauri, a globular cluster, and other celestial sights. (See; https://www.skyandtelescope.com/observing/beginners-guide-to-the-southern-hemisphere-sky/).

2. The Sun, Moon, and stars represented in art

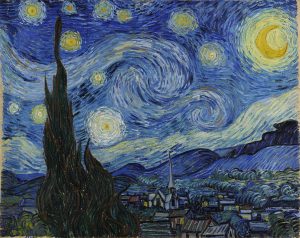

Many artists have noticed and portrayed the Sun, Moon, and stars. The Dutch artist Vincent Van Gogh, for example, included them in many paintings such as The Sower at Sunset in 1888 and The Starry Night in 1889 as shown in Fig. 5.5 and Fig. 5.6.

The dominant “star” to the lower right of the cypress tree in Fig. 5.6 has been identified as in an appropriate location to represent the planet Venus at the time the artist was making this painting.

3. The Sun, Moon, and stars represented in poetry

Many poems about the Sun, Moon, and stars reflect primarily upon the writer’s emotions, situation, and surroundings. Several poets, however, have described physical aspects of ways that the Sun, Moon, and stars appear to move and/or look.

Robert Louis Stevenson, for example, described the Sun’s apparent motion around the Earth as it seems to create on-going experiences of morning after morning. Children on one side of the Earth are getting up and playing while those on the other side of the Earth are going to bed.

The Sun Travels By Robert Louis Stevenson

The Sun is not a-bed, when I

At night upon my pillow lie;

Still round the earth his way he takes,

And morning after morning makes.

While here at home, in shining day,

We round the sunny garden play,

Each little Indian sleepy-head

Is being kissed and put to bed.

And when at eve I rise from tea,

Day dawns beyond the Atlantic Sea;

And all the children in the West

Are getting up and being dressed.

A Child’s Garden of Verses, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905, p. 35.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25609/25609-h/25609-h.htm#THE_SUN_TRAVELS/

In a three-line poem, Winter Moon, Langston Hughes commented briefly upon the shape of a crescent moon (see: https://www.worldcat.org/title/dream-keeper-and-other-poems/oclc/36310693/viewport), in The Dream Keepers and Other Poems published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. in 1932, page 3). In the poem Invention, Billy Collins offered a whimsical description of the Moon’s changing phases. (see: https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/poetry/antholog/collins/invent.htm, published in the Atlantic Monthly in December, 1998, Volume 282, No. 6, page 92).

A poem by Jane Taylor, set to the French tune Ah! vous dirai-je, maman, has been sung as a lullaby for more than two centuries.

The Star

By Jane Taylor

Twinkle, twinkle little star,

How I wonder what you are!

Up above the world so high,

Like a diamond in the sky.

When this blazing sun is gone,

When he nothing shines upon,

Then you show your little light,

Twinkle, twinkle, through the night.

Then the traveler in the dark

Thanks you for your tiny spark;

He could not see where to go,

If you did not twinkle so.

In the dark blue sky you keep,

And often through my curtains peep,

For you never shut your eye,

Till the sun is in the sky.

As your bright and tiny spark,

Lights the traveler in the dark,

Though I know not what you are,

Twinkle, twinkle, little star.

Rhymes for the Nursery, London: Darton and Harvey, 1806

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/first-publication-of-twinkle-twinkle-little-star/

This lullaby can be thought of as introducing nascent scientific processes: noticing a phenomenon of interest (twinkle, twinkle, little star), questioning (how I wonder what you are), observing (up above the world so high) and starting to think about what one is seeing by making an analogy (like a diamond in the sky). The poem also correlates occurrences (when this blazing sun is gone…then you show your little light…; for you never shut your eye, till the sun is in the sky), and ponders what is not yet understood (though I know not what you are) while celebrating again the phenomenon observed (twinkle, twinkle, little star).

Question 5.4 How early in life does a child start noticing the sky?

4. A young child’s observations of the Moon in the sky: Joseph’s Moon

Young children often notice what is happening in the sky, as described by a graduate student below:

Joseph is my nephew. At the time of this story, he was about 17 months old…My father often takes care of Joseph and I think I was talking about our moon assignments. My father said that he had recently taken Joseph to the nearby park one afternoon and that Joseph had pointed and said, “Moo.” My father said he was looking for a cow (not a likely event for this suburban park!)…

My father finally realized that Joseph was pointing at the sky and that yes indeed there was a moon in the daytime sky. (When referring to the moon at this time, Joseph would point and say, “Moo.”) [Hey! Could this be a relationship between the moon and the cow who jumped over it??]

At this point, my sister told a similar story. When Joseph pointed into the daytime sky and said, “Moo,” my sister said something like, “There’s no moon in the sky, it’s daytime.” Joseph was persistent though (not that he could necessarily understand his mother yet) and finally brought my sister to realize that there was a moon in the sky during daylight hours. [I’m not sure if Joseph is ready for Grad school yet, but I think that during the fall semester, he made more moon observations than some of the students in our class!]

Some Reflections on the Moon [Isn’t this what causes the phases?] and Joseph:

I suppose what impresses me most is the awareness of a one-and-a-half-year-old child of the moon. At this point in time there seemed to be almost a fascination with the moon. We could say that this is due to it’s being a brightly lit object in a dark sky, but the moon is much less obvious in the daytime sky. In fact, I often have to search for the moon in the daytime sky; it usually doesn’t just jump out at you…

So adults with all their “experience” may take things for granted; things that might not really be true. Joseph’s mother and grandfather both, by their comments, indicate that they were operating under the rule “The moon only appears at night.” Joseph seems to have straightened them out on this point.

I believe that it is a good exercise for students to go back to the basics of observation, to become like a child who has no preconceived rules as to how the world works. All too often in the lab we manage to get what we expect by writing off the “bad” points. In many cases in science history those “bad” points weren’t so bad after all and led to advances in science.

Science education graduate student

Question 5.5 How do people talk together about the Moon?

People all over the world see and talk about the moon. For the word for moon in more than eighty languages see https://www.indifferentlanguages.com/words/moon . Watching the moon together can provide common ground for students from different cultures to enjoy talking with and learning from one another. For information about a global moon watching project, see http://www.worldmoonproject.org or contact Professor Walter Smith at walter.smith@ttu.edu .

5. Ways of speaking about the Moon in a first-grade bilingual classroom

A first-grade teacher, Deborah Roberts, described what happened when she engaged her students in watching the moon:

More than half of my class is enrolled in a bilingual program that is part of the English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) program in our school; many students wrote their moon journals in Spanish. Parents helped with spelling, and some wrote what their child dictated. Parents felt successful in helping their children in their native language whether it was English or Spanish, and children felt successful in observing the moon. Spanish-speaking students felt confident when sharing their journal with the class. The English speakers were also learning some Spanish; everyone knew luna meant moon and noche meant night. So when someone shared their picture and their entry, anoche yo vi la luna así (last night I saw the moon like this), many non-Spanish speakers understood part of the entry before they saw the picture. Sometimes a Spanish-speaking child would teach the class how to say what he or she wrote.

Deborah Roberts. “The sky’s the limit: Parents and first-grade students observe the sky.”Science and Children, 31(1), 33-37. (September, 1999).

Some schools choose a theme each year for which all classes in all grades contribute. Watching the moon sometimes has served this role as a context within which students of all ages can participate.