4.7: Rock Cycle Processes

- Page ID

- 5367

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Is this what geologists mean by the rock cycle?

Okay, maybe not. The rock cycle shows how any type of rock can become any other type of rock. The three rock types are joined together by the processes that change one to another.

The Rock Cycle

You learned about the three rock types: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic. You also learned that all of these rocks can change. In fact, any rock can change to become any other type of rock. These changes usually happen very slowly. Some changes happen below Earth’s surface. Some changes happen above ground. These changes are all part of the rock cycle. The rock cycle describes each of the main types of rocks, how they form, and how they change.

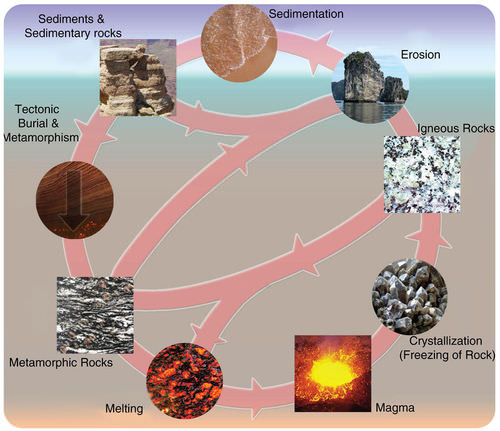

The figure below shows how the three main rock types are related to each other (Figure below). The arrows within the circle show how one type of rock may change to rock of another type. These are the processes that change one rock type to another rock type.

The Rock Cycle.

Processes of the Rock Cycle

There are three main processes that can change rock:

- Cooling and crystallization. Deep within the Earth, temperatures can get hot enough to create magma. As magma cools, crystals grow, forming igneous rock. The crystals grow larger if the magma cools slowly, as it does if it remains deep within the Earth. If the magma cools quickly, the crystals will be very small. When crystals form from magma it is called crystallization.

- Weathering and erosion. Water, wind, ice, and even plants and animals all act to wear down rocks. Over time they can break larger rocks into sediments. Rocks break down by the process called weathering. Moving water, wind, and glaciers then carry these pieces from one place to another. This is called erosion. The sediments are eventually dropped, or deposited, somewhere. This process is called sedimentation. The sediments may then be compacted and cemented together. This forms a sedimentary rock. This whole process can take hundreds or thousands of years.

- Metamorphism. This long word means “to change form.“ A rock undergoes metamorphism if it is exposed to extreme heat and pressure within the crust. With metamorphism, the rock does not melt all the way. The rock changes due to heat and pressure. A metamorphic rock may have a new mineral composition and/or texture.

The rock cycle really has no beginning or end. It just continues. The processes involved in the rock cycle take place over hundreds, thousands, or even millions of years. Even though for us rocks are solid and unchanging, they slowly change all the time.

Summary

- The three main rock types are igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary.

- The three processes that change one rock to another are crystallization, metamorphism, and erosion and sedimentation.

- Any rock can transform into any other rock by passing through one or more of these processes. This creates the rock cycle.

Review

- What processes create igneous rocks?

- What processes create metamorphic rocks?

- What processes create sedimentary rocks?

Explore More

Use this video to answer the questions that follow.

- What are the three rock types?

- What happens to sedimentary rocks on Earth’s surface?

- What happens over time to make sediments into sedimentary rocks?

- How can you tell a sedimentary rock from another type?

- What happens to a sedimentary rock if you apply heat and pressure?

- How might this happen?

- How does an igneous rock form?

- What causes the structures of igneous rocks to be different?

- How can an igneous rock become a sedimentary rock? A metamorphic rock?

- What are the three rock types?

- What happens to sedimentary rocks on Earth’s surface?

- What happens over time to make sediments into sedimentary rocks?

- How can you tell a sedimentary rock from another type?

- What happens to a sedimentary rock if you apply heat and pressure?

- How might this happen?

- How does an igneous rock form?

- What causes the structures of igneous rocks to be different?

- How can an igneous rock become a sedimentary rock? A metamorphic rock?