15.10: Tree Rings, Ice Cores, and Varves

- Page ID

- 5904

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)How could you tell the age of this ruin?

Mesa Verde in Southwestern Colorado is the site of beautiful cliff dwellings. The people who inhabited these dwellings are long gone. If you go there you will hear the history of the area, complete with dates. How do archeologists know when the people lived here? How do they know the ages of the structures there? Tree ring dating is extremely useful for finding the age of ancient structures.

Tree Ring Dating

Cut into a tree and you can see its rings. In some locations, the summer growth band is light-colored and the winter band is dark. Each light-dark band represents one year. You can tell how long the tree lived by counting the number of tree rings (Figure below). Age dating by tree rings is called dendrochronology.

Cross-section showing growth rings.

You can tell other things from tree rings too. In a good year a tree will produce a wide ring. A summer drought will produce a smaller ring. These variations will appear in all trees in a region. The same pattern can be found in all the trees in the area. This pattern helps scientist to identify a particular time period.

Scientists have records of tree rings going back over the past 2,000 years. By matching up patterns they can tell when a tree (or a piece of wood from one) lived. Wood fragments from old buildings and ancient ruins can be age dated. The outermost ring gives the date when the tree died.

Ice Cores

Other processes create yearly layers that can be used for dating. On a glacier, snow falls in winter. In summer, dust accumulates. This leads to a snow-dust annual pattern. This pattern can be seen down into the ice (Figure below). Scientists drill deep into ice sheets. Ice cores can be hundreds of meters long. The ice cores show how the environment has changed. Gas bubbles in the ice can be analyzed to show how atmospheric gases have changed. This can yield clues about climate. Long ice cores have allowed scientists to create a record of polar climate going back hundreds of thousands of years.

Ice core section showing annual layers.

Varves

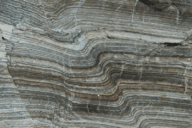

Lake sediments also have an annual pattern. This is easy to see in lakes that are located at the end of glaciers. The glacier melts rapidly in the summer. This produces a thick deposit of sediment in the lake. Thin, clay-rich layers are deposited in the winter. The resulting layers are called varves. Varves give scientists clues about past climate conditions (Figure below). A warm summer might result in a very thick sediment layer. A cooler summer might yield a thinner layer. Like tree rings, these patterns can be used to identify time periods.

Ancient varve sediments in a rock outcrop.

Summary

- Where conditions vary seasonally, trees develop distinctive rings. Ice contains more or less dust. Lake sediments show more or less clay.

- Tree rings, ice cores, and varves indicate the environmental conditions at the time they were made.

- The distinctive patterns of tree rings, ice cores, and varves go back thousands of years. They can be used to determine the time they were made.

Review

- Why are these three dating methods considered absolute age dating?

- Describe how tree rings indicate time. Do the same for ice cores and varves.

- Describe how tree rings, ice cores, and varves indicate what was going on in the environment when they formed.

Explore More

Use the resources below to answer the questions that follow.

- What do annual tree rings tell scientists?

- What can be learned from tree rings?

- What do tree rings indicate about the lost colony of Roanoke, Virginia?

- What type of trees do scientists look for? Why?

- What is trapped in the ice cores and when it it from?

- How long have ice cores been studied?

- What can be learned from ice cores?

- What circumstances make the best ice cores? What is a good location to obtain cores like this?

- How much would sea level rise if the Greenland ice sheet melted?