3.2.6: Solving Trigonometric Equations Using Basic Algebra

- Page ID

- 4231

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Substitute in potential solutions or solve using inverse trig functions.

As Agent Trigonometry, you are given this clue: \(2 \sin x−\sqrt{2}=0\). If \(0\leq x<2\pi\), what is/are the value(s) of \(x\).

Solving Trigonometric Equations

We have already verified trigonometric identities, which are true for every real value of \(x\). In this concept, we will solve trigonometric equations. An equation is only true for some values of \(x\).

Let's verify that \(\csc x−2=0\) when \(x=\dfrac{5\pi}{6}\).

Substitute in \(x=\dfrac{5\pi}{6}\) to see if the equations holds true.

\(\begin{aligned} \csc \left(\dfrac{5\pi}{6}\right)−2&=0\\ \dfrac{1}{\sin \left(\dfrac{5\pi}{6}\right)}−2&=0 \\ \dfrac{1}{\dfrac{1}{2}}−2&=0 \\ 2−2&=0\end{aligned}\)

This is a true statement, so \(x=\dfrac{5\pi}{6}\) is a solution to the equation.

Now, let's solve \(2\cos x+1=0\).

To solve this equation, we need to isolate cosx and then use inverse to find the values of x when the equation is valid.

\(\begin{aligned} 2\cos x+1&=0 \\ 2\cos x&=−1 \\ \cos x&=−\dfrac{1}{2}\end{aligned}\)

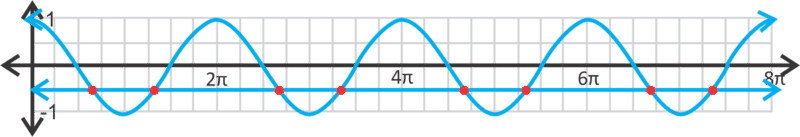

So, when is the \(\cos x=−\dfrac{1}{2}\)? Between \(0\leq x<2\pi\), \(x=\dfrac{2\pi}{3}\) and \(\dfrac{4\pi}{3}\). But, the trig functions are periodic, so there are more solutions than just these two. You can write the general solutions as \(x=\dfrac{2\pi}{3} \pm 2\pi n\) and \(x=\dfrac{4\pi}{3}\pm 2\pi n\), where \(n\) is any integer. You can check your answer graphically by graphing \(y=\cos x\) and \(y=−\dfrac{1}{2}\) on the same set of axes. Where the two lines intersect are the solutions.

Finally, let's solve \(5 \tan(x+2)−1=0\), where \(0\leq x<2\pi\).

In this problem, we have an interval where we want to find \(x\). Therefore, at the end of the problem, we will need to add or subtract \(\pi\), the period of tangent, to find the correct solutions within our interval.

\(\begin{aligned} 5 \tan(x+2)−1&=0 \\ 5 \tan(x+2)&=1 \\ \tan(x+2)&=\dfrac{1}{5} \end{aligned}\)

Using the tan−1 button on your calculator, we get that \(\tan^{−1} \left(\dfrac{1}{5}\right)=0.1974\). Therefore, we have:

\(\begin{aligned} x+2&=0.1974 \\ x&=−1.8026 \end{aligned}\)

This answer is not within our interval. To find the solutions in the interval, add \(\pi \) a couple of times until we have found all of the solutions in \([0,2\pi ]\).

\(\begin{aligned} x&=−1.8026+\pi =1.3390 \\ &=1.3390+\pi =4.4806\end{aligned}\)

The two solutions are \(x=1.3390\) and \(4.4806\).

Earlier, you were asked to find the value of x from the equation \(2\sin x−\sqrt{2}=0\).

Solution

To solve this equation, we need to isolate \(\sin x\) and then use inverse to find the values of \(x\) when the equation is valid.

\(\begin{aligned} 2 \sin x−\sqrt{2}&=0 \\ 2\sin x&=\sqrt{2} \\ \sin x&=\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\end{aligned}\)

So now we need to find the values of \(x\) for which \(\sin x=\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\). We know from the special triangles that this value of sine holds true for a \(45^{\circ}\) angle, but is that the only value of \(x\) for which it is true?

We are told that \(0\leq x<2\pi\). Recall that the sine is positive in both the first and second quadrants, so \(\sin x=\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) when \(x\) also is \(135^{\circ}\).

Determine if \(x=\dfrac{\pi}{3}\) is a solution for \(2\sin x=\sqrt{3}\).

Solution

\(2\sin \dfrac{\pi}{3}=\sqrt{3} \rightarrow 2 \cdot \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}=\sqrt{3}\)

Yes, \(x=\dfrac{\pi}{3}\) is a solution.

Solve the following trig equation in the interval \(0\leq x<2\pi\).

\(3 \cos^2 x−5=0\)

Solution

\(\begin{aligned} 9\cos^2x−5&=0 \\ 9\cos^2x&=5 \\ \cos^2 x&=\dfrac{5}{9} \\ \cos x=\pm \dfrac{\sqrt{5}}{3}\end{aligned}\)

The \(\cos x=\dfrac{\sqrt{5}}{3}\) at \(x=0.243 \text{rad}\) (use your graphing calculator). To find the other value where cosine is positive, subtract 0.243 from \(2\pi\), \(x=2\pi −0.243=6.037\text{ rad}\).

The \(\cos x=−\dfrac{\sqrt{5}}{3}\) at \(x=2.412 \text{rad}\), which is in the \(2^{nd}\) quadrant. To find the other value where cosine is negative (the \(3^{rd}\) quadrant), use the reference angle, 0.243, and add it to \(\pi\). \(x=\pi +0.243=3.383\text{ rad}\).

Solve the following trig equation in the interval \(0\leq x<2\pi\).

\(3\sec(x−1)+2=0\)

Solution

Here, we will find the solution within the given range, \(0\leq x<2\pi\).

\(\begin{aligned} 3\sec(x−1)+2&=0 \\ 3\sec(x−1)&=−2 \\ \sec(x−1)&=−\dfrac{2}{3} \\ \cos(x−1)&=−\dfrac{3}{2}\end{aligned}\)

At this point, we can stop. The range of the cosine function is from 1 to -1. \(−\dfrac{3}{2}\) is outside of this range, so there is no solution to this equation.

Review

Determine if the following values for x. are solutions to the equation \(5+6 \csc x=17\).

- \(x=−\dfrac{7\pi }{6}\)

- \(x=\dfrac{11\pi }{6}\)

- \(x=\dfrac{5\pi }{6}\)

Solve the following trigonometric equations. If no solutions exist, write no solution.

- \(1−\cos x=0\)

- \(3\tan x−\sqrt{3}=0\)

- \(4\cos x=2\cos x+1\)

- \(5 \sin x−2=2 \sin x+4\)

- \(\sec x−4=−\sec x\)

- \(\tan^2(x−2)=3\)

Sole the following trigonometric equations within the interval \(0\leq x<2\pi\). If no solutions exist, write no solution.

- \(\cos x=\sin x\)

- \(−\sqrt{3} \csc x=2\)

- \(6\sin(x−2)=14\)

- \(7\cos x−4=1\)

- \(5+4\cot^2 x=17\)

- \(2\sin^2x−7=−6\)

Answers for Review Problems

To see the Review answers, open this PDF file and look for section 14.10.

Additional Resources

Practice: Solving Trigonometric Equations Using Basic Algebra