14.1: The Sociology of Education

- Page ID

- 3448

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Objectives

- Explain the different views held by functionalist, conflict, and interactionist sociologist with regards to education.

- Describe some of the issues affecting American education system.

Universal Generalizations

- Every society has developed a system education to ensure its new members become functioning members of society.

- The basic function of education is to teach children the knowledge and skills they will need in the world.

- For societies to survive, they must transmit the core values of their culture to the following generations.

- Education is used throughout societies to socialize their young to support their communities’ own social and political systems.

- Schools help to teach socially acceptable forms of behavior.

- All societies must have some system for identifying and training he young people who will do the important work of society in the future.

- Most Americans believe education is the key to social mobility and possible economic success.

- Since the foundation of the United States, education has been highly valued.

Guiding Questions

- How do we learn what it means to be an American?

- What is the purpose of education?

- How does education influence society?

- What is the difference between formal and informal education?

- What is the functionalist view on education?

- What is the conflict perspective on education?

- How do sociologists view education using the interactionist view?

The Sociology of Education

From the moment a child is born, his or her education begins. At first, education is an informal process in which an infant watches others and imitates them. As the infant grows into a young child, the process of education becomes more formal through play dates and preschool. Once in grade school, academic lessons become the focus of education as a child moves through the school system. But even then, education is about much more than the simple learning of facts.

Our education system also socializes us to our society. We learn cultural expectations and norms, which are reinforced by our teachers, our textbooks, and our classmates. (For students outside the dominant culture, this aspect of the education system can pose significant challenges.) You might remember learning your multiplication tables in second grade and also learning the social rules of taking turns on the swings at recess. You might recall learning about the U.S. Constitution in an American Government course as well as learning when and how to speak up in class.

Schools also can be agents of change, teaching individuals to think outside of the family norms into which they were born. Educational environments can broaden horizons and even help to break cycles of poverty and racism.

Of course, America’s schools are often criticized—for not producing desired test results, or for letting certain kids slip through the cracks. In all, sociologists understand education to be both a social problem and a social solution.

Education in the United States

Education is the social institution through which a society teaches its members the skills, knowledge, norms, and values they need to learn to become good, productive members of their society. As this definition makes clear, education is an important part of socialization. Education is both formal andinformal. Formal education is often referred to as schooling, and as this term implies, it occurs in schools under teachers, principals, and other specially trained professionals. Informal educationmay occur almost anywhere, but for young children it has traditionally occurred primarily in the home, with their parents as their instructors. Day care has become an increasingly popular venue in industrial societies for young children’s instruction, and education from the early years of life is thus more formal than it used to be.

The major sociological perspectives on education fall nicely into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009).Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2009).The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. "Theory Snapshot" summarizes what these approaches say.

Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

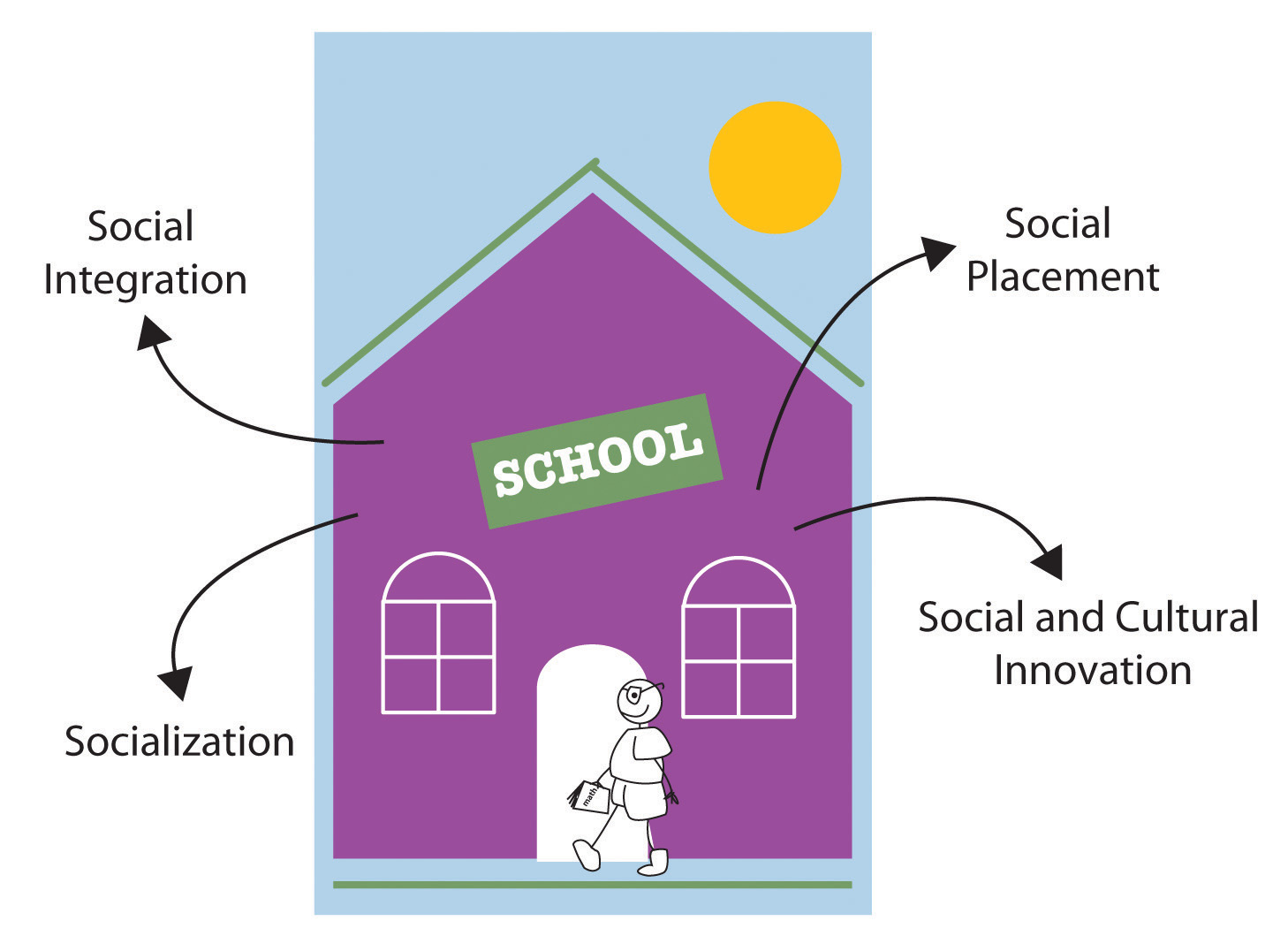

| Functionalism | Education serves several functions for society. These include (a) socialization, (b) social integration, (c) social placement, and (d) social and cultural innovation. Latent functions include child care, the establishment of peer relationships, and lowering unemployment by keeping high school students out of the full-time labor force. |

| Conflict theory | Education promotes social inequality through the use of tracking and standardized testing and the impact of its “hidden curriculum.” Schools differ widely in their funding and learning conditions, and this type of inequality leads to learning disparities that reinforce social inequality. |

| Symbolic interactionism | This perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. Specific research finds that social interaction in schools affects the development of gender roles and that teachers’ expectations of pupils’ intellectual abilities affect how much pupils learn. |

The Functions of Education

Functional theory stresses the functions that education serves in fulfilling a society’s various needs. Perhaps the most important function of education is socialization. If children need to learn the norms, values, and skills they need to function in society, then education is a primary vehicle for such learning. Schools teach the three Rs, as we all know, but they also teach many of the society’s norms and values. In the United States, these norms and values include respect for authority, patriotism (remember the Pledge of Allegiance?), punctuality, individualism, and competition. Regarding these last two values, American students from an early age compete as individuals over grades and other rewards.

A second function of education is social integration. For a society to work, functionalists say, people must subscribe to a common set of beliefs and values. As we saw, the development of such common views was a goal of the system of free, compulsory education that developed in the 19th century. Thousands of immigrant children in the United States today are learning English, U.S. history, and other subjects that help prepare them for the workforce and integrate them into American life. Such integration is a major goal of the English-only movement, whose advocates say that only English should be used to teach children whose native tongue is Spanish, Vietnamese, or whatever other language their parents speak at home. Critics of this movement say it slows down these children’s education and weakens their ethnic identity (Schildkraut, 2005).Schildkraut, D. J. (2005). Press “one” for English: Language policy, public opinion, and American identity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

A third function of education is social placement. Beginning in grade school, students are identified by teachers and other school officials either as bright and motivated or as less bright and even educationally challenged. Depending on how they are identified, children are taught at the level that is thought to suit them best. In this way they are prepared in the most appropriate way possible for their later station in life. Whether this process works as well as it should is an important issue, and we explore it further when we discuss school tracking shortly.

Social and cultural innovation is a fourth function of education. Our scientists cannot make important scientific discoveries and our artists and thinkers cannot come up with great works of art, poetry, and prose unless they have first been educated in the many subjects they need to know for their chosen path.

The Functionalist Perspective on Education

Functionalists view education as one of the more important social institutions in a society. They contend that education contributes two kinds of functions: manifest (or primary) functions, which are the intended and visible functions of education; and latent (or secondary) functions, which are the hidden and unintended functions.

Manifest Functions

There are several major manifest functions associated with education. The first is socialization. Beginning in preschool and kindergarten, students are taught to practice various societal roles. The French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), who established the academic discipline of sociology, characterized schools as “socialization agencies that teach children how to get along with others and prepare them for adult economic roles” (Durkheim 1898). Indeed, it seems that schools have taken on this responsibility in full.

This socialization also involves learning the rules and norms of the society as a whole. In the early days of compulsory education, students learned the dominant culture. Today, since the culture of the United States is increasingly diverse, students may learn a variety of cultural norms, not only that of the dominant culture.

School systems in the United States also transmit the core values of the nation through manifest functions like social control. One of the roles of schools is to teach students conformity to law and respect for authority. Obviously, such respect, given to teachers and administrators, will help a student navigate the school environment. This function also prepares students to enter the workplace and the world at large, where they will continue to be subject to people who have authority over them. Fulfillment of this function rests primarily with classroom teachers and instructors who are with students all day.

Education also provides one of the major methods used by people for upward social mobility. This function is referred to as social placement. College and graduate schools are viewed as vehicles for moving students closer to the careers that will give them the financial freedom and security they seek. As a result, college students are often more motivated to study areas that they believe will be advantageous on the social ladder. A student might value business courses over a class in Victorian poetry because she sees business class as a stronger vehicle for financial success.

Latent Functions

Education also fulfills latent functions. As you well know, much goes on in a school that has little to do with formal education. For example, you might notice an attractive fellow student when he gives a particularly interesting answer in class—catching up with him and making a date speaks to the latent function of courtship fulfilled by exposure to a peer group in the educational setting.

The educational setting introduces students to social networks that might last for years and can help people find jobs after their schooling is complete. Of course, with social media such as Facebook and LinkedIn, these networks are easier than ever to maintain. Another latent function is the ability to work with others in small groups, a skill that is transferable to a workplace and that might not be learned in a homeschool setting.

The educational system, especially as experienced on university campuses, has traditionally provided a place for students to learn about various social issues. There is ample opportunity for social and political advocacy, as well as the ability to develop tolerance to the many views represented on campus. In 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement swept across college campuses all over the United States, leading to demonstrations in which diverse groups of students were unified with the purpose of changing the political climate of the country.

| Manifest Functions: Openly stated functions with intended goals | Latent Functions: Hidden, unstated functions with sometimes unintended consequences |

|---|---|

| Socialization | Courtship |

| Transmission of culture | Social networks |

| Social control | Working in groups |

| Social placement | Creation of generation gap |

| Cultural innovation | Political and social integration |

Functionalists recognize other ways that schools educate and enculturate students. One of the most important American values students in the United States learn is that of individualism—the valuing of the individual over the value of groups or society as a whole. In countries such as Japan and China, where the good of the group is valued over the rights of the individual, students do not learn as they do in the United States that the highest rewards go to the “best” individual in academics as well as athletics. One of the roles of schools in the United States is fostering self-esteem; conversely, schools in Japan focus on fostering social esteem—the honoring of the group over the individual.

In the United States, schools also fill the role of preparing students for competition in life. Obviously, athletics foster a competitive nature, but even in the classroom students compete against one another academically. Schools also fill the role of teaching patriotism. Students recite the Pledge of Allegiance each morning and take history classes where they learn about national heroes and the nation’s past.

Another role of schools, according to functionalist theory, is that of sorting, or classifying students based on academic merit or potential. The most capable students are identified early in schools through testing and classroom achievements. Such students are placed in accelerated programs in anticipation of successful college attendance.

Functionalists also contend that school, particularly in recent years, is taking over some of the functions that were traditionally undertaken by family. Society relies on schools to teach about human sexuality as well as basic skills such as budgeting and job applications—topics that at one time were addressed by the family.

Conflict Theory on Education

Conflict theorists do not believe that public schools reduce social inequality. Rather, they believe that the educational system reinforces and perpetuates social inequalities arising from differences in class, gender, race, and ethnicity. Where functionalists see education as serving a beneficial role, conflict theorists view it more negatively. To them, educational systems preserve the status quo and push people of lower status into obedience.

The fulfillment of one’s education is closely linked to social class. Students of low socioeconomic status are generally not afforded the same opportunities as students of higher status, no matter how great their academic ability or desire to learn. Picture a student from a working-class home who wants to do well in school. On a Monday, he’s assigned a paper that’s due Friday. Monday evening, he has to babysit his younger sister while his divorced mother works. Tuesday and Wednesday, he works stocking shelves after school until 10:00 p.m. By Thursday, the only day he might have available to work on that assignment, he’s so exhausted he can’t bring himself to start the paper. His mother, though she’d like to help him, is so tired herself that she isn’t able to give him the encouragement or support he needs. And since English is her second language, she has difficulty with some of his educational materials. They also lack a computer and printer at home, which most of his classmates have, so they have to rely on the public library or school system for access to technology. As this story shows, many students from working class families have to contend with helping out at home, contributing financially to the family, poor study environments and a lack of support from their families. This is a difficult match with education systems that adhere to a traditional curriculum that is more easily understood and completed by students of higher social classes.

Education and Inequality

Conflict theory does not dispute most of the functions just described. However, it does give some of them a different slant and talks about various ways in which education perpetuates social inequality (Hill, Macrine, & Gabbard, 2010; Liston, 1990).Hill, D., Macrine, S., & Gabbard, D. (Eds.). (2010).Capitalist education: Globalisation and the politics of inequality. New York, NY: Routledge; Liston, D. P. (1990). Capitalist schools: Explanation and ethics in radical studies of schooling. New York, NY: Routledge. One example involves the function of social placement. As most schools track their students starting in grade school, the students thought by their teachers to be bright are placed in the faster tracks (especially in reading and arithmetic), while the slower students are placed in the slower tracks; in high school, three common tracks are the college track, vocational track, and general track.

Conflict theorists point to tracking, a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities. While educators may believe that students do better in tracked classes because they are with students of similar ability and may have access to more individual attention from teachers, conflict theorists feel that tracking leads to self-fulfilling prophecies in which students live up (or down) to teacher and societal expectations (Education Week 2004).

Such tracking does have its advantages; it helps ensure that bright students learn as much as their abilities allow them, and it helps ensure that slower students are not taught over their heads. But, conflict theorists say, tracking also helps perpetuate social inequality by locking students into faster and lower tracks. Worse yet, several studies show that students’ social class and race and ethnicity affect the track into which they are placed, even though their intellectual abilities and potential should be the only things that matter: white, middle-class students are more likely to be tracked “up,” while poorer students and students of color are more likely to be tracked “down.” Once they are tracked, students learn more if they are tracked up and less if they are tracked down. The latter tend to lose self-esteem and begin to think they have little academic ability and thus do worse in school because they were tracked down. In this way, tracking is thought to be good for those tracked up and bad for those tracked down. Conflict theorists thus say that tracking perpetuates social inequality based on social class and race and ethnicity (Ansalone, 2006; Oakes, 2005).Ansalone, G. (2006). Tracking: A return to Jim Crow. Race, Gender & Class, 13, 1–2; Oakes, J. (2005). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality (2nd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Social inequality is also perpetuated through the widespread use of standardized tests. Critics say these tests continue to be culturally biased, as they include questions whose answers are most likely to be known by white, middle-class students, whose backgrounds have afforded them various experiences that help them answer the questions. They also say that scores on standardized tests reflect students’ socioeconomic status and experiences in addition to their academic abilities. To the extent this critique is true, standardized tests perpetuate social inequality (Grodsky, Warren, & Felts, 2008).Grodsky, E., Warren, J. R., & Felts, E. (2008). Testing and social stratification in American education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 385–404.

To conflict theorists, schools play the role of training working class students to accept and retain their position as lower members of society. They argue that this role is fulfilled through the disparity of resources available to students in richer and poorer neighborhoods as well as through testing (Lauen and Tyson 2008).

IQ tests have been attacked for being biased—for testing cultural knowledge rather than actual intelligence. For example, a test item may ask students what instruments belong in an orchestra. To correctly answer this question requires certain cultural knowledge—knowledge most often held by more affluent people who typically have more exposure to orchestral music. Though experts in testing claim that bias has been eliminated from tests, conflict theorists maintain that this is impossible. These tests, to conflict theorists, are another way in which education does not provide opportunities, but instead maintains an established configuration of power.

Conflict theorists also say that schooling teaches a hidden curriculum, by which they mean a set of values and beliefs that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy (Booher-Jennings, 2008) Booher-Jennings, J. (2008). Learning to label: Socialisation, gender, and the hidden curriculum of high-stakes testing. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29, 149–160. Although no one plots this behind closed doors, our schoolchildren learn patriotic values and respect for authority from the books they read and from various classroom activities.

Interactionist Perspective on Education

Symbolic interactionist studies of education examine social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. These studies help us understand what happens in the schools themselves, but they also help us understand how what occurs in school is relevant for the larger society. Some studies, for example, show how children’s playground activities reinforce gender-role socialization. Girls tend to play more cooperative games, while boys play more competitive sports (Thorne, 1993)Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Research also shows that teachers’ views about students can affect how much the students learn. When teachers think students are smart, they tend to spend more time with them, to call on them, and to praise them when they give the right answer. Not surprisingly these students learn more because of their teachers’ behavior. But when teachers think students are less bright, they tend to spend less time with them and act in a way that leads the students to learn less. One of the first studies to find this example of a self-fulfilling prophecy was conducted by Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson (1968).Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. New York, NY: Holt. They tested a group of students at the beginning of the school year and told their teachers which students were bright and which were not. They tested the students again at the end of the school year; not surprisingly the bright students had learned more during the year than the less bright ones. But it turned out that the researchers had randomly decided which students would be designated bright and less bright. Because the “bright” students learned more during the school year without actually being brighter at the beginning, their teachers’ behavior must have been the reason. In fact, their teachers did spend more time with them and praised them more often than was true for the “less bright” students. To the extent this type of self-fulfilling prophecy occurs, it helps us understand why tracking is bad for the students tracked down.

Other research focuses on how teachers treat girls and boys. Several studies from the 1970s through the 1990s found that teachers call on boys more often and praise them more often (American Association of University Women Educational Foundation, 1998; Jones & Dindia, 2004).American Association of University Women Educational Foundation. (1998). Gender gaps: Where schools still fail our children. Washington, DC: American Association of University Women Educational Foundation; Jones, S. M., & Dindia, K. (2004). A meta-analystic perspective on sex equity in the classroom. Review of Educational Research, 74, 443–471. Teachers did not do this consciously, but their behavior nonetheless sent an implicit message to girls that math and science are not for girls and that they are not suited to do well in these subjects. This body of research stimulated efforts to educate teachers about the ways in which they may unwittingly send these messages and about strategies they could use to promote greater interest and achievement by girls in math and science (Battey, Kafai, Nixon, & Kao, 2007).Battey, D., Kafai, Y., Nixon, A. S., & Kao, L. L. (2007). Professional development for teachers on gender equity in the sciences: Initiating the conversation. Teachers College Record, 109(1), 221–243.

Key Takeaways

- According to the functional perspective, education helps socialize children and prepare them for their eventual entrance into the larger society as adults.

- The conflict perspective emphasizes that education reinforces inequality in the larger society.

- The symbolic interactionist perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on school playgrounds, and at other school-related venues. Social interaction contributes to gender-role socialization, and teachers’ expectations may affect their students’ performance.

Education in the United States

Education in the United States is a massive social institution involving millions of people and billions of dollars. About 75 million people, almost one-fourth of the U.S. population, attend school at all levels. This number includes 40 million in grades pre-K through 8, 16 million in high school, and 19 million in college (including graduate and professional school). They attend some 132,000 elementary and secondary schools and about 4,200 2-year and 4-year colleges and universities and are taught by about 4.8 million teachers and professors (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Retrieved from www.census.gov/compendia/statab Education is a huge social institution.

Correlates of Educational Attainment

About 65% of U.S. high school graduates enroll in college the following fall. This is a very high figure by international standards, as college in many other industrial nations is reserved for the very small percentage of the population who pass rigorous entrance exams. They are the best of the brightest in their nations, whereas higher education in the United States is open to all who graduate high school. Even though that is true, our chances of achieving a college degree are greatly determined at birth, as social class and race/ethnicity have a significant effect on access to college. They affect whether students drop out of high school, in which case they do not go on to college; they affect the chances of getting good grades in school and good scores on college entrance exams; they affect whether a family can afford to send its children to college; and they affect the chances of staying in college and obtaining a degree versus dropping out. For these reasons, educational attainment depends heavily on family income and race and ethnicity.

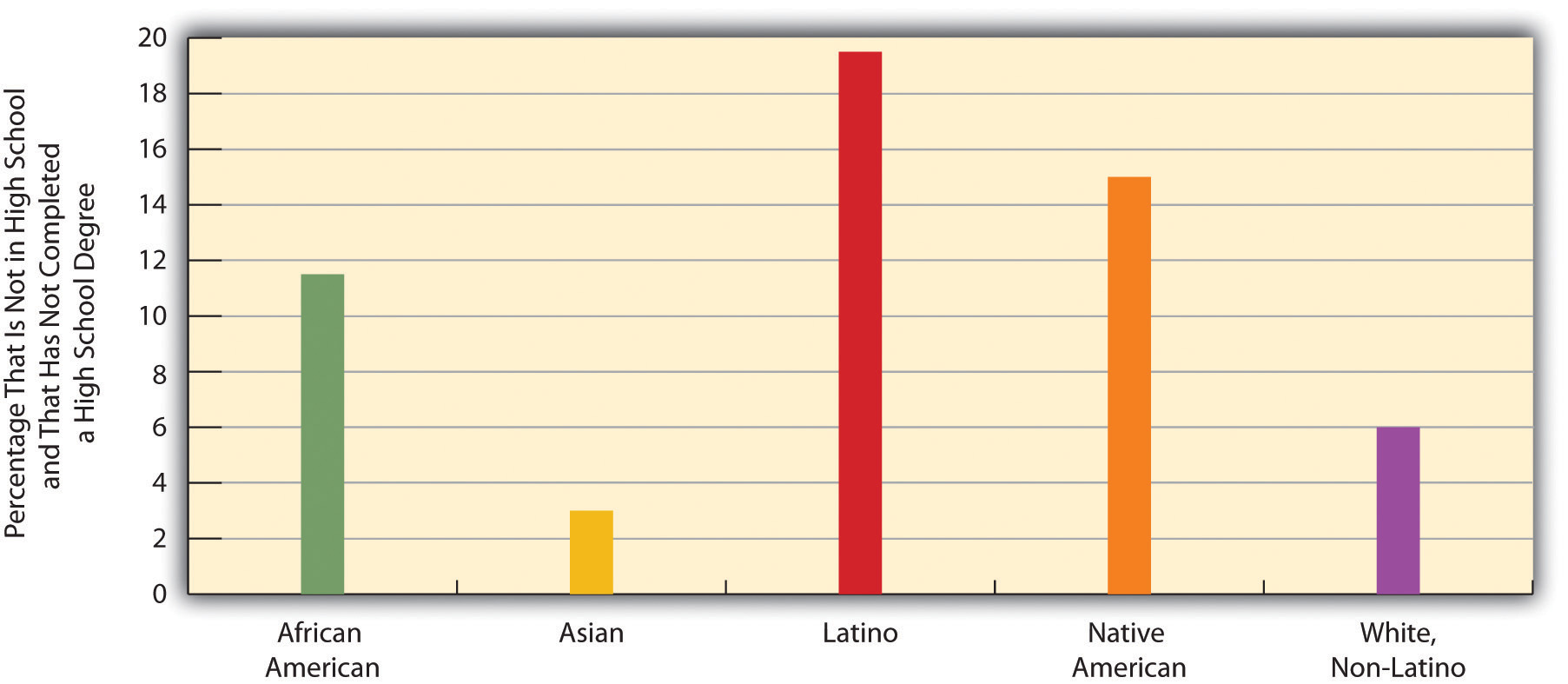

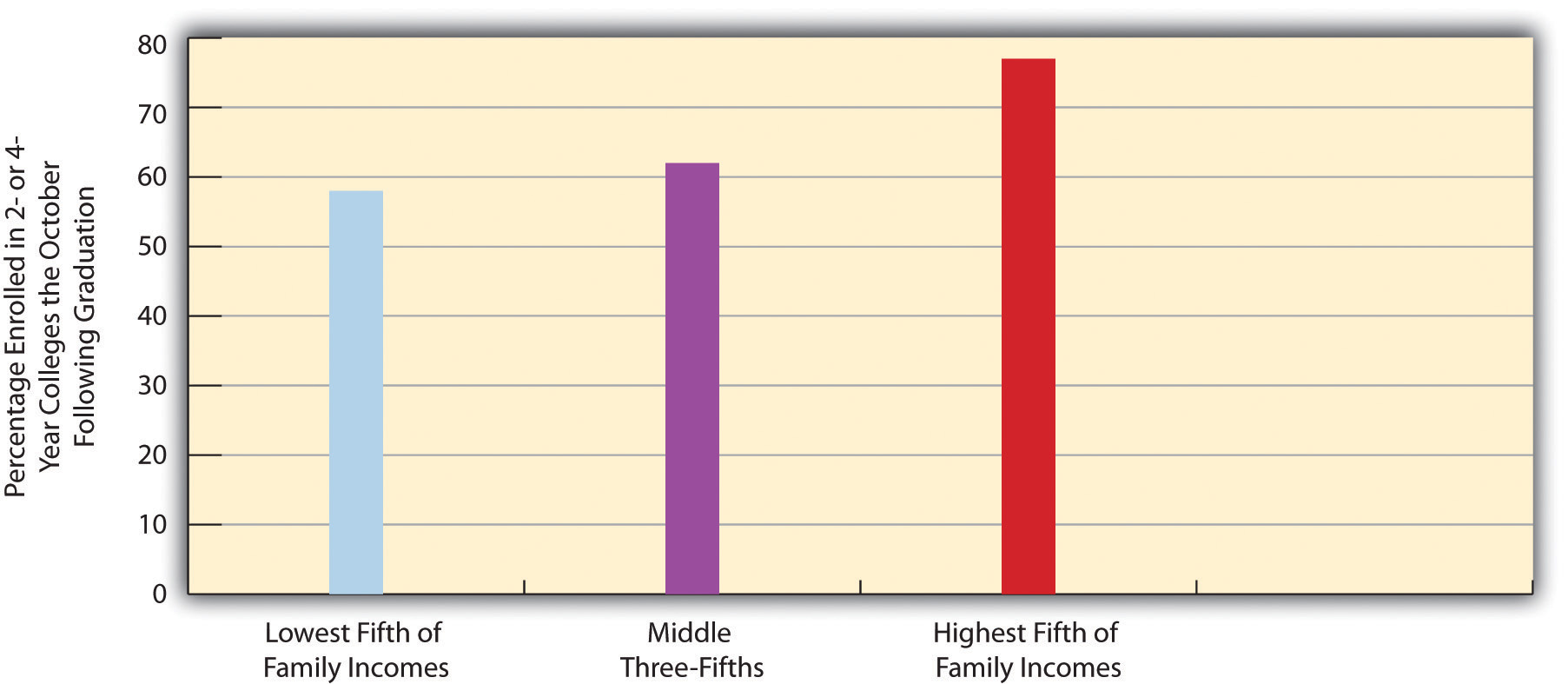

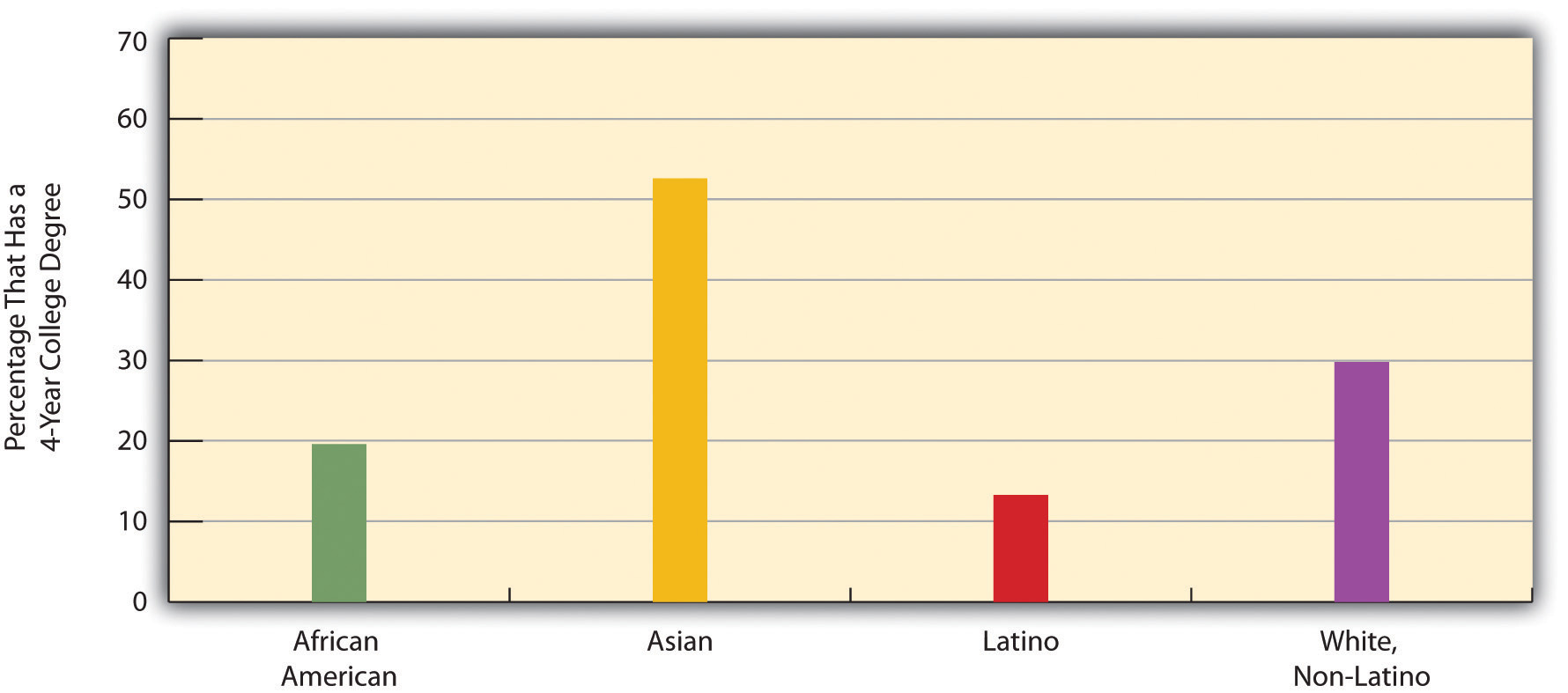

Figure 14.1.6 "Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007" shows how race and ethnicity affect dropping out of high school. The dropout rate is highest for Latinos and Native Americans and lowest for Asians and whites. One way of illustrating how income and race/ethnicity affect the chances of achieving a college degree is to examine the percentage of high school graduates who enroll in college immediately following graduation. As Figure 14.1.7 "Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007" shows, students from families in the highest income bracket are more likely than those in the lowest bracket to attend college. For race/ethnicity, it is useful to see the percentage of persons 25 or older who have at least a 4-year college degree. As Figure 14.1.8 "Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008" shows, this percentage varies significantly, with African Americans and Latinos least likely to have a degree.

Why do African Americans and Latinos have lower educational attainment? Two factors are commonly cited: (a) the underfunded and otherwise inadequate schools that children in both groups often attend and (b) the higher poverty of their families and lower education of their parents that often leave them ill-prepared for school even before they enter kindergarten (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009; Yeung & Pfeiffer, 2009).Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2009). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; Yeung, W.-J. J., & Pfeiffer, K. M. (2009). The black-white test score gap and early home environment. Social Science Research, 38(2), 412–437.

Issues in Education

As schools strive to fill a variety of roles in their students’ lives, many issues and challenges arise. Students walk a minefield of bullying, violence in schools, the results of declining funding, plus other problems that affect their education. When Americans are asked about their opinion of public education on the Gallup poll each year, reviews are mixed at best (Saad 2008). Schools are no longer merely a place for learning and socializing. With the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling in 1954, schools became a repository of much political and legal action that is at the heart of several issues in education.

Equal Education

Until the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, schools had operated under the precedent set by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, which allowed racial segregation in schools and private businesses (the case dealt specifically with railroads) and introduced the much maligned phrase “separate but equal” into the United States lexicon. The 1954 Brown v. Board decision overruled this, declaring that state laws that had established separate schools for black and white students were, in fact, unequal and unconstitutional.

While the ruling paved the way toward civil rights, it was also met with contention in many communities. In Arkansas in 1957, the governor mobilized the state National Guard to prevent black students from entering Little Rock Central High School. President Eisenhower, in response, sent members of the 101st Airborne Division from Kentucky to uphold the students’ right to enter the school. In 1963, almost ten years after the ruling, Governor George Wallace of Alabama used his own body to block two black students from entering the auditorium at the University of Alabama to enroll in the school. Wallace’s desperate attempt to uphold his policy of “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” stated during his 1963 inauguration (PBS 2000) became known as the “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door.” He refused to grant entry to the students until a general from the Alabama National Guard arrived on President Kennedy’s order.

Presently, students of all races and ethnicities are permitted into schools, but there remains a troubling gap in the equality of education they receive. The long-term socially embedded effects of racism—and other discrimination and disadvantage—have left a residual mark of inequality in the nation’s education system. Students from wealthy families and those of lower socioeconomic status do not receive the same opportunities.

Today’s public schools, at least in theory, are positioned to help remedy those gaps. Predicated on the notion of universal access, this system is mandated to accept and retain all students regardless of race, religion, social class, and the like. Moreover, public schools are held accountable to equitable per-student spending (Resnick 2004). Private schools, usually only accessible to students from high-income families, and schools in more affluent areas generally enjoy access to greater resources and better opportunities. In fact, some of the key predictors for student performance include socioeconomic status and family background. Children from families of lower socioeconomic status often enter school with learning deficits they struggle to overcome throughout their educational tenure. These patterns, uncovered in the landmark Coleman Report of 1966, are still highly relevant today, as sociologists still generally agree that there is a great divide in the performance of white students from affluent backgrounds and their non-white, less affluent, counterparts (Coleman 1966).

No Child Left Behind

In 2001, the Bush administration passed the No Child Left Behind Act, which requires states to test students in designated grades. The results of those tests determine eligibility to receive federal funding. Schools that do not meet the standards set by the Act run the risk of having their funding cut. Sociologists and teachers alike have contended that the impact of the No Child Left Behind Act is far more negative than positive, arguing that a “one size fits all” concept cannot apply to education.

Bilingual Education

New issues of inequality have entered the national conversation in recent years with the issue of bilingual education, which attempts to give equal opportunity to minority students through offering instruction in languages other than English. Though it is actually an old issue (bilingual education was federally mandated in 1968), it remains one of hot debate. Supporters of bilingual education argue that all students deserve equal opportunities in education—opportunities some students cannot access without instruction in their first language. On the other side, those who oppose bilingual education often point to the need for English fluency in everyday life and in the professional world.

Charter Schools

Charter schools are self-governing public schools that have signed agreements with state governments to improve students when poor performance is revealed on tests required by the No Child Left Behind Act. While such schools receive public money, they are not subject to the same rules that apply to regular public schools. In return, they make agreements to achieve specific results. Charter schools, as part of the public education system, are free to attend, and are accessible via lottery when there are more students seeking enrollment than there are spots available at the school. Some charter schools specialize in certain fields, such as the arts or science, while others are more generalized.

Home Schooling

Homeschooling refers to children being educated in their own homes, typically by a parent, instead of in a traditional public or private school system. Proponents of this type of education argue that it provides an outstanding opportunity for student-centered learning while circumventing problems that plague today’s education system. Opponents counter that home-schooled children miss out on the opportunity for social development that occurs in standard classroom environments and school settings.

Proponents say that parents know their own children better than anyone else and are thus best equipped to teach them. Those on the other side of the debate assert that childhood education is a complex task and requires the degree teachers spend four years earning. After all, they argue, a parent may know her child’s body better than anyone, yet she seeks out a doctor for her child’s medical treatment. Just as a doctor is a trained medical expert, teachers are trained education experts.

The National Center for Education Statistics shows that the quality of the national education system isn’t the only major concern of homeschoolers. While nearly half cite their reason for homeschooling as the belief that they can give their child a better education than the school system can, just under 40 percent choose homeschooling for “religious reasons” (NCES 2008). To date, researchers have not found consensus in studies evaluating the success, or lack thereof, of homeschooling.

Teaching to the Test

The funding tie-in of the No Child Left Behind Act has led to the social phenomenon commonly called “teaching to the test,” which describes when a curriculum focuses on equipping students to succeed on standardized tests, to the detriment of broader educational goals and concepts of learning. At issue are two approaches to classroom education: the notion that teachers impart knowledge that students are obligated to absorb, versus the concept of student-centered learning that seeks to teach children not facts, but problem solving abilities and learning skills. Both types of learning have been valued in the American school system. The former, to critics of “teaching to the test,” only equips students to regurgitate facts, while the latter, to proponents of the other camp, fosters lifelong learning and transferable work skills.

School Vouchers and School Choice

Another issue involving schools today is school choice. In a school choice program, the government gives parents certificates, or vouchers, that they can use as tuition at private or parochial (religious) schools.

Advocates of school choice programs say they give poor parents an option for high-quality education they otherwise would not be able to afford. These programs, the advocates add, also help improve the public schools by forcing them to compete for students with their private and parochial counterparts. In order to keep a large number of parents from using vouchers to send their children to the latter schools, public schools have to upgrade their facilities, improve their instruction, and undertake other steps to make their brand of education an attractive alternative. In this way, school choice advocates argue, vouchers have a “competitive impact” that forces public schools to make themselves more attractive to prospective students (Walberg, 2007).Walberg, H. J. (2007). School choice: The findings. Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

Critics of school choice programs say they hurt the public schools by decreasing their enrollments and therefore their funding. Public schools do not have the money now to compete with private and parochial ones, and neither will they have the money to compete with them if vouchers become more widespread. Critics also worry that voucher programs will lead to a “brain drain” of the most academically motivated children and families from low-income schools (Caldas & Bankston, 2005).Caldas, S. J., & Bankston, C. L., III. (2005). Forced to fail: The paradox of school desegregation. Westport, CT: Praeger.

School Violence

The issue of school violence won major headlines during the 1990s, when many children, teachers, and other individuals died in the nation’s schools. From 1992 until 1999, 248 students, teachers, and other people died from violent acts (including suicide) on school property, during travel to and from school, or at a school-related event, for an average of about 35 violent deaths per year (Zuckoff, 1999).Zuckoff, M. (1999, May 21). Fear is spread around nation. The Boston Globe, p. A1. Against this backdrop, the infamous April 1999 school shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, where two students murdered 12 other students and one teacher before killing themselves, led to national soul-searching over the causes of teen and school violence and on possible ways to reduce it.

The murders in Littleton were so numerous and cold-blooded that they would have aroused national concern under any circumstances, but they also followed a string of other mass shootings at schools. In just a few examples, in December 1997 a student in a Kentucky high school shot and killed three students in a before-school prayer group. In March 1998 two middle school students in Arkansas pulled a fire alarm to evacuate their school and then shot and killed four students and one teacher as they emerged. Two months later an Oregon high school student killed his parents and then went to his school cafeteria, where he killed two students and wounded 22 others. Against this backdrop, Littleton seemed like the last straw. Within days, school after school across the nation installed metal detectors, located police at building entrances and in hallways, and began questioning or suspending students joking about committing violence. People everywhere wondered why the schools were becoming so violent and what could be done about it (Zuckoff, 1999).Zuckoff, M. (1999, May 21). Fear is spread around nation. The Boston Globe, p. A1.

Violence can also happen on college and university campuses, although shootings are very rare. However, two recent examples illustrate that students and faculty are not immune from gun violence. In February 2010, Amy Bishop, a biology professor at the University of Alabama in Huntsville who had recently been denied tenure, allegedly shot and killed three faculty at a department meeting and wounded three others. Almost 3 years earlier, a student at Virginia Tech went on a shooting rampage and killed 32 students and faculty before killing himself.