14.2: The Sociology of Religion

- Page ID

- 3449

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Objectives

- Describe the basic societal needs religion fulfills.

- Describe the distinctive features of religion in American society.

Universal Generalizations

- Religion is a societal creation and a universal phenomenon.

- At the center of all religions is the distinction between the sacred and the profane.

- Many believe religion serves certain essential functions in all societies.

- Religion exists in various forms around the world.

- All religions contain certain basic characteristics.

Guiding Questions

- How important is religion in your life?

- What is religion from a sociological perspective?

- What is the meaning of sacred?

- How can religion provide social control?

- What roles do rituals and symbols play in the nature of religion?

- What are the main differences and similarities between monotheism and polytheism?

The Sociology of Religion

Why do sociologists study religion? For centuries, humankind has sought to understand and explain the “meaning of life.” Many philosophers believe this contemplation and the desire to understand our place in the universe are what differentiate humankind from other species. Religion, in one form or another, has been found in all human societies since human societies first appeared. Archaeological digs have revealed ritual objects, ceremonial burial sites, and other religious artifacts. Social conflict and even wars often result from religious disputes. To understand a culture, sociologists must study its religion.

From the Latin religio (respect for what is sacred) and religare (to bind, in the sense of an obligation), the term religion describes various systems of belief and practice concerning what people determine to be sacred or spiritual (Fasching and deChant 2001; Durkheim 1915). Throughout history, and in societies across the world, leaders have used religious narratives, symbols, and traditions in an attempt to give more meaning to life and understand the universe. Some form of religion is found in every known culture, and it is usually practiced in a public way by a group. The practice of religion can include feasts and festivals, God or gods, marriage and funeral services, music and art, meditation or initiation, sacrifice or service, and other aspects of culture.

What is religion? Pioneer sociologist Emile Durkheim described it with the ethereal statement that it consists of “things that surpass the limits of our knowledge” (1915). He went on to elaborate: Religion is “a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say set apart and forbidden, beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community, called a church, all those who adhere to them” (1915). Some people associate religion with places of worship (a synagogue or church), others with a practice (confession or meditation), and still others with a concept that guides their daily lives (like dharma or sin). All of these people can agree that religion is a system of beliefs, values, and practices concerning what a person holds sacred or considers to be spiritually significant.

Religion can also serve as a filter for examining other issues in society and other components of a culture. For example, after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, it became important for teachers, church leaders, and the media to educate Americans about Islam to prevent stereotyping and to promote religious tolerance. Sociological tools and methods, such as surveys, polls, interviews, and analysis of historical data, can be applied to the study of religion in a culture to help us better understand the role religion plays in people’s lives and the way it influences society.

Religion - A Sociological Definition

Religion clearly plays an important role in American life. Most Americans believe in a deity, three-fourths pray at least weekly, and more than half attend religious services at least monthly. We tend to think of religion in individual terms because religious beliefs and values are highly personal for many people. However, religion is also a social institution, as it involves patterns of beliefs and behavior that help a society meet its basic needs. Because it is such an important social institution, religion has long been a key sociological topic. Émile Durkheim (1915/1947)Durkheim, É. (1947).The elementary forms of religious life (J. Swain, Trans.). Glencoe, IL: Free Press. (Original work published 1915) observed long ago that every society has beliefs about things that are supernatural and awe-inspiring and beliefs about things that are more practical and down-to-earth. He called the former beliefs sacred beliefs and the latter beliefs profane beliefs. Religious beliefs and practices involve the sacred: they involve things our senses cannot readily observe, and they involve things that inspire in us awe, reverence, and even fear.

Durkheim did not try to prove or disprove religious beliefs. Religion, he acknowledged, is a matter of faith, and faith is not provable or disprovable through scientific inquiry. Rather, Durkheim tried to understand the role played by religion in social life and the impact on religion of social structure and social change. In short, he treated religion as a social institution.

Sociologists since his time have treated religion in the same way. Anthropologists, historians, and other scholars have also studied religion. Historical work on religion reminds us of the importance of religion since the earliest societies, while comparative work on contemporary religion reminds us of its importance throughout the world today.

The Functions of Religion

Sociological perspectives on religion aim to understand the functions religion serves, the inequality and other problems it can reinforce and perpetuate, and the role it plays in our daily lives (Emerson, Monahan, & Mirola, 2011).Emerson, M. O., Monahan, S. C., & Mirola, W. A. (2011). Religion matters: What sociology teaches us about religion in our world. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. "Theory Snapshot" summarizes what these perspectives say.

Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Religion serves several functions for society. These include (a) giving meaning and purpose to life, (b) reinforcing social unity and stability, (c) serving as an agent of social control of behavior, (d) promoting physical and psychological well-being, and (e) motivating people to work for positive social change. |

| Conflict theory | Religion reinforces and promotes social inequality and social conflict. It helps convince the poor to accept their lot in life, and it leads to hostility and violence motivated by religious differences. |

| Symbolic interactionism | This perspective focuses on the ways in which individuals interpret their religious experiences. It emphasizes that beliefs and practices are not sacred unless people regard them as such. Once they are regarded as sacred, they take on special significance and give meaning to people’s lives. |

Much of the work of Émile Durkheim stressed the functions that religion serves for society regardless of how it is practiced or of what specific religious beliefs a society favors. Durkheim’s insights continue to influence sociological thinking today on the functions of religion.

First, religion gives meaning and purpose to life. Many things in life are difficult to understand. That was certainly true, as we have seen, in prehistoric times, but even in today’s highly scientific age, much of life and death remains a mystery, and religious faith and belief help many people make sense of the things science cannot tell us.

Second, religion reinforces social unity and stability. This was one of Durkheim’s most important insights. Religion strengthens social stability in at least two ways. First, it gives people a common set of beliefs and thus is an important agent of socialization. Second, the communal practice of religion, as in houses of worship, brings people together physically, facilitates their communication and other social interaction, and thus strengthens their social bonds.

A third function of religion is related to the one just discussed. Religion is an agent of social control and thus strengthens social order. Religion teaches people moral behavior and thus helps them learn how to be good members of society. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the Ten Commandments are perhaps the most famous set of rules for moral behavior.

The communal practice of religion in a house of worship brings people together and allows them to interact and communicate. In this way religion helps reinforce social unity and stability. This function of religion was one of Émile Durkheim’s most important insights.

A fourth function of religion is greater psychological and physical well-being. Religious faith and practice can enhance psychological well-being by being a source of comfort to people in times of distress and by enhancing their social interaction with others in places of worship. Many studies find that people of all ages, not just the elderly, are happier and more satisfied with their lives if they are religious. Religiosity also apparently promotes better physical health, and some studies even find that religious people tend to live longer than those who are not religious (Moberg, 2008).Moberg, D. O. (2008). Spirituality and aging: Research and implications. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 20, 95–134. We return to this function later.

A final function of religion is that it may motivate people to work for positive social change. Religion played a central role in the development of the Southern civil rights movement a few decades ago. Religious beliefs motivated Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists to risk their lives to desegregate the South. Black churches in the South also served as settings in which the civil rights movement held meetings, recruited new members, and raised money (Morris, 1984).Morris, A. (1984). The origins of the civil rights movement: Black communities organizing for change. New York, NY: Free Press.

The Nature of Religion

Symbolic interactionism examines the role that religion plays in our daily lives and the ways in which we interpret religious experiences. For example, it emphasizes that beliefs and practices are not sacred unless people regard them as such. Once we regard them as sacred, they take on special significance and give meaning to our lives. Symbolic interactionists study the ways in which people practice their faith and interact in houses of worship and other religious settings, and they study how and why religious faith and practice have positive consequences for individual psychological and physical well-being.

Religious symbols indicate the value of the symbolic interactionist approach. A crescent moon and a star are just two shapes in the sky, but together they constitute the international symbol of Islam. A cross is merely two lines or bars in the shape of a “t,” but to tens of millions of Christians it is a symbol with deeply religious significance. A Star of David consists of two superimposed triangles in the shape of a six-pointed star, but to Jews around the world it is a sign of their religious faith and a reminder of their history of persecution.

Religious rituals and ceremonies also illustrate the symbolic interactionist approach. They can be deeply intense and can involve crying, laughing, screaming, trancelike conditions, a feeling of oneness with those around you, and other emotional and psychological states. For many people they can be transformative experiences, while for others they are not transformative but are deeply moving nonetheless.

Belief Systems

Scholars from a variety of disciplines have strived to classify religions. One widely accepted categorization that helps people understand different belief systems considers what or who people worship (if anything). Using this method of classification, religions might fall into one of these basic categories, as shown in Figure 14.2.3.

| Religious Classification | What/Who Is Divine | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polytheism | Multiple gods | Ancient Greeks and Romans |

| Monotheism | Single god | Judaism, Islam |

| Atheism | No deities | Atheism |

| Animism | Nonhuman beings (animals, plants, natural world) | Indigenous nature worship (Shinto) |

| Totemism | Human-natural being connection | Ojibwa (Native American) |

Note that some religions may be practiced—or understood—in various categories. For instance, the Christian notion of the Holy Trinity (God, Jesus, Holy Spirit) defies the definition of monotheism to some scholars. Similarly, many Westerners view the multiple manifestations of Hinduism’s godhead as polytheistic, while Hindus might describe those manifestations are a monotheistic parallel to the Christian Trinity.

It is also important to note that every society also has nonbelievers, such as atheists, who do not believe in a divine being or entity, and agnostics, who hold that ultimate reality (such as God) is unknowable. While typically not an organized group, atheists and agnostics represent a significant portion of the population. It is important to recognize that being a nonbeliever in a divine entity does not mean the individual subscribes to no morality. Indeed, many Nobel Peace Prize winners and other great humanitarians over the centuries would have classified themselves as atheists or agnostics.

Organizational Structure of Religion

Many types of religious organizations exist in modern societies. Sociologists usually group them according to their size and influence. Categorized this way, three types of religious organizations exist: church, sect, and cult (Emerson, Monahan, & Mirola, 2011).Emerson, M. O., Monahan, S. C., & Mirola, W. A. (2011). Religion matters: What sociology teaches us about religion in our world. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. A church further has two subtypes: the ecclesia and denomination. We first discuss the largest and most influential of the types of religious organization, the ecclesia, and work our way down to the smallest and least influential, the cult.

Church: The Ecclesia and Denomination

A church is a large, bureaucratically organized religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society. Two types of church organizations exist. The first is the ecclesia, a large, bureaucratic religious organization that is a formal part of the state and has most or all of a state’s citizens as its members. As such, the ecclesia is the national or state religion. People ordinarily do not join an ecclesia; instead they automatically become members when they are born. A few ecclesiae exist in the world today, including Islam in Saudi Arabia and some other Middle Eastern nations, the Catholic Church in Spain, the Lutheran Church in Sweden, and the Anglican Church in England.

As should be clear, in an ecclesiastic society there may be little separation of church and state, because the ecclesia and the state are so intertwined. In some ecclesiastic societies, such as those in the Middle East, religious leaders rule the state or have much influence over it, while in others, such as Sweden and England, they have little or no influence. In general the close ties that ecclesiae have to the state help ensure they will support state policies and practices. For this reason, ecclesiae often help the state solidify its control over the populace.

The second type of church organization is the denomination, a large, bureaucratic religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society but is not a formal part of the state. In modern pluralistic nations, several denominations coexist. Most people are members of a specific denomination because their parents were members. They are born into a denomination and generally consider themselves members of it the rest of their lives, whether or not they actively practice their faith, unless they convert to another denomination or abandon religion altogether.

The Megachurch

A relatively recent development in religious organizations is the rise of the so-called megachurch, a church at which more than 2,000 people worship every weekend on the average. Several dozen have at least 10,000 worshippers (Priest, Wilson, & Johnson, 2010; Warf & Winsberg, 2010);Priest, R. J., Wilson, D., & Johnson, A. (2010). U.S. megachurches and new patterns of global mission.International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 34(2), 97–104; Warf, B., & Winsberg, M. (2010). Geographies of megachurches in the United States. Journal of Cultural Geography, 27(1), 33–51. the largest U.S. megachurch, in Houston, has more than 35,000 worshippers and is nicknamed a “gigachurch.”

There are more than 1,300 megachurches in the United States, a steep increase from the 50 that existed in 1970, and their total membership exceeds 4 million. About half of today’s megachurches are in the South, and only 5% are in the Northeast. About one-third are nondenominational, and one-fifth are Southern Baptist, with the remainder primarily of other Protestant denominations. A third spend more than 10% of their budget on ministry in other nations. Some have a strong television presence, with Americans in the local area or sometimes around the country watching services and/or preaching by televangelists and providing financial contributions in response to information presented on the television screen.

Compared to traditional, smaller churches, megachurches are more concerned with meeting their members’ practical needs in addition to helping them achieve religious fulfillment. Some even conduct market surveys to determine these needs and how best to address them. As might be expected, their buildings are huge by any standard, and they often feature bookstores, food courts, and sports and recreation facilities. They also provide day care, psychological counseling, and youth outreach programs. Their services often feature electronic music and light shows.

Although megachurches are popular, they have been criticized for being so big that members are unable to develop the close bonds with each other and with members of the clergy characteristic of smaller houses of worship. Their supporters say that megachurches involve many people in religion who would otherwise not be involved.

Sect

A sect is a relatively small religious organization that is not closely integrated into the larger society and that often conflicts with at least some of its norms and values. Typically a sect has broken away from a larger denomination in an effort to restore what members of the sect regard as the original views of the denomination. Because sects are relatively small, they usually lack the bureaucracy of denominations and ecclesiae and often also lack clergy who have received official training. Their worship services can be intensely emotional experiences, often more so than those typical of many denominations, where worship tends to be more formal and restrained. Members of many sects typically proselytize and try to recruit new members into the sect. If a sect succeeds in attracting many new members, it gradually grows, becomes more bureaucratic, and, ironically, eventually evolves into a denomination. Many of today’s Protestant denominations began as sects, as did the Mennonites, Quakers, and other groups. The Amish in the United States are perhaps the most well-known example of a current sect.

Cult

A cult is a small religious organization that is at great odds with the norms and values of the larger society. Cults are similar to sects but differ in at least three respects. First, they generally have not broken away from a larger denomination and instead originate outside the mainstream religious tradition. Second, they are often secretive and do not proselytize as much. Third, they are at least somewhat more likely than sects to rely oncharismatic leadership based on the extraordinary personal qualities of the cult’s leader.

Although the term cult today raises negative images of crazy, violent, small groups of people, it is important to keep in mind that major world religions, including Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, and denominations such as the Mormons all began as cults. Research challenges several popular beliefs about cults, including the ideas that they brainwash people into joining them and that their members are mentally ill. In a study of the Unification Church (Moonies), Eileen Barker (1984)Barker, E. (1984).The making of a Moonie: Choice or brainwashing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. found no more signs of mental illness among people who joined the Moonies than in those who did not. She also found no evidence that people who joined the Moonies had been brainwashed into doing so.

Another image of cults is that they are violent. In fact, most are not violent. However, some cults have committed violence in the recent past. In 1995 the Aum Shinrikyo (Supreme Truth) cult in Japan killed 10 people and injured thousands more when it released bombs of deadly nerve gas in several Tokyo subway lines (Strasser & Post, 1995).Strasser, S., & Post, T. (1995, April 3). A cloud of terror—and suspicion. Newsweek 36–41. Two years earlier, the Branch Davidian cult engaged in an armed standoff with federal agents in Waco, Texas. When the agents attacked its compound, a fire broke out and killed 80 members of the cult, including 19 children; the origin of the fire remains unknown (Tabor & Gallagher, 1995).Tabor, J. D., & Gallagher, E. V. (1995). Why Waco? Cults and the battle for religious freedom in America. Berkeley: University of California Press. A few cults have also committed mass suicide.

In another example from the 1990's, more than three dozen members of the Heaven’s Gate cult killed themselves in California in March 1997 in an effort to communicate with aliens from outer space (Hoffman & Burke, 1997).Hoffman, B., & Burke, K. (1997). Heaven’s Gate: Cult suicide in San Diego. New York, NY: Harper Paperbacks. Some two decades earlier, more than 900 members of the People’s Temple cult killed themselves in Guyana under orders from the cult’s leader, Jim Jones (Stoen, 1997).Stoen, T. (1997, April 7). The most horrible night of my life. Newsweek 44–45.

Religion in the United States

The United States is generally regarded as a fairly religious nation. In a 2009 survey administered by the Gallup Organization to 114 nations, 65% of Americans answered yes when asked, “Is religion an important part of your daily life?” (Crabtree, 2010).Crabtree, S. (2010). Religiosity highest in world’s poorest nations. In a 2007 Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life survey, about 83% of Americans expressed a religious preference, 61% were official members of a local house of worship, and 39% attended religious services at least weekly (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2008).Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2008). U.S. religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. These figures show that religion plays a significant role in the lives of many Americans.

Moreover, Americans seem more religious than the citizens of almost all the other democratic, industrialized nations with which the United States is commonly compared. Evidence for this conclusion comes from the 2009 Gallup survey mentioned in the preceding paragraph. Whereas 65% of Americans said religion was an important part of their daily lives, comparable percentages from other democratic, industrialized nations included the following: Spain, 49%; Canada, 42%; France, 30%; United Kingdom, 27%; and Sweden, 17% (Crabtree, 2010).Crabtree, S. (2010). Religiosity highest in world’s poorest nations. Among its peer nations, then, the United States stands out for being religious.

When we consider all the nations of the world, however, the U.S. ranking is much lower. In more than half the nations surveyed by Gallup in 2009, at least 84% of respondents said religion was an important part of their daily lives. The U.S. rate of 65% ranked 85th out of the 114 nations in this survey (Crabtree, 2010).Crabtree, S. (2010). Religiosity highest in world’s poorest nations. However, because the United States ranks higher than most of the democratic, industrialized nations with which it is most aptly compared, it makes sense to regard the United States as fairly religious.

Religious Affiliation and Religious Identification

Religious affiliation is a term that can mean actual membership in a church or synagogue, or just a stated identification with a particular religion whether or not someone actually belongs to a local house of worship. Another term for religious affiliation is religious preference. Recall from the Pew survey cited earlier that 83% of Americans express a religious preference, while 61% are official members of a local house of worship. As these figures indicate, more people identify with a religion than actually belong to it.

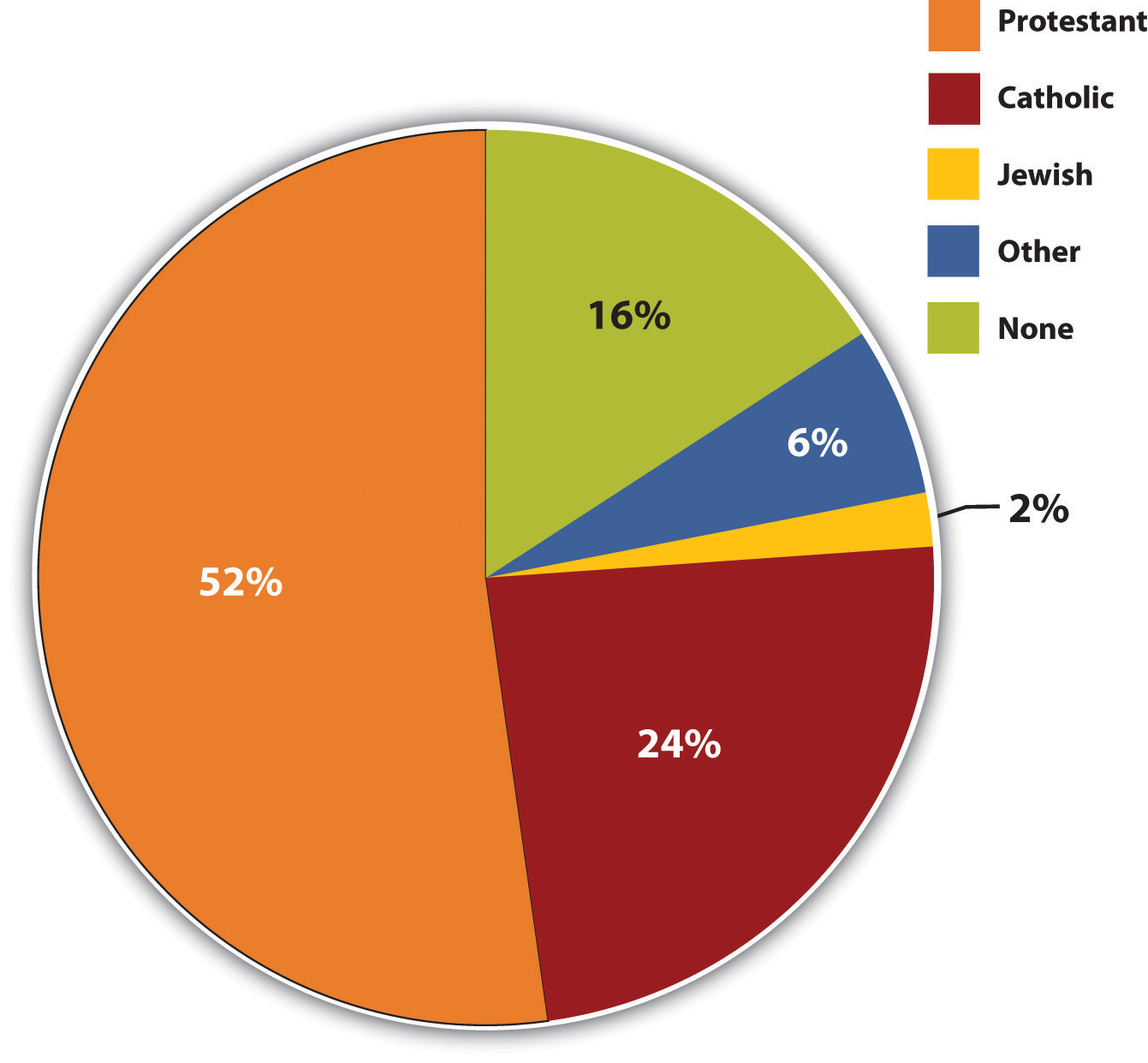

The Pew survey also included some excellent data on religious identification (see Figure "Religious Preference in the United States"). Slightly more than half of Americans say their religious preference is Protestant, while about 24% call themselves Catholic. Almost 2% say they are Jewish, while 6% state another religious preference and 16% say they have no religious preference. Although Protestants are thus a majority of the country, the Protestant religion includes several denominations. About 34% of Protestants are Baptists; 12% are Methodists; 9% are Lutherans; 9% are Pentecostals; 5% are Presbyterians; and 3% are Episcopalians. The remainder identify with other Protestant denominations or say their faith is nondenominational. Based on their religious beliefs, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists are typically grouped together as Liberal Protestants; Methodists, Lutherans, and a few other denominations as Moderate Protestants; and Baptists, Seventh-Day Adventists, and many other denominations as Conservative Protestants.

Correlates of Religious Affiliation

The religious affiliations just listed differ widely in the nature of their religious belief and practice, but they also differ in demographic variables of interest to sociologists (Finke & Stark, 2005).Finke, R., & Stark, R. (2005). The churching of America: Winners and losers in our religious economy (2nd ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. For example, Liberal Protestants tend to live in the Northeast and to be well educated and relatively wealthy, while Conservative Protestants tend to live in the South and to be less educated and working-class. In their education and incomes, Catholics and Moderate Protestants fall in between these two groups. Like Liberal Protestants, Jews also tend to be well educated and relatively wealthy.

Race and ethnicity are also related to religious affiliation. African Americans are overwhelmingly Protestant, usually Conservative Protestants (Baptists), while Latinos are primarily Catholic. Asian Americans and Native Americans tend to hold religious preferences other than Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish.

Age is yet another factor related to religious affiliation, as older people are more likely than younger people to belong to a church or synagogue. As young people marry and “put roots down,” their religious affiliation increases, partly because many wish to expose their children to a religious education. In the Pew survey, 25% of people aged 18–29 expressed no religious preference, compared to only 8% of those 70 or older.

Religiosity

People can belong to a church, synagogue, or mosque or claim a religious preference, but that does not necessarily mean they are very religious. For this reason, sociologists consider religiosity, or the significance of religion in a person’s life, an important topic of investigation.

Religiosity has a simple definition but actually is a very complex topic. What if someone prays every day but does not attend religious services? What if someone attends religious services but never prays at home and does not claim to be very religious? Someone can pray and read a book of scriptures daily, while someone else can read a book of scriptures daily but pray only sometimes. As these possibilities indicate, a person can be religious in some ways but not in other ways.

For this reason, religiosity is best conceived of as a concept involving several dimensions: experiential, ritualistic, ideological, intellectual, and consequential (Stark & Glock, 1968).Stark, R., & Glock, C. Y. (1968). Patterns of religious commitment. Berkeley: University of California Press. Experiential religiosity refers to how important people consider religion to be in their lives and is the dimension used by the international Gallup Poll discussed earlier. Ritualistic religiosity refers to the extent of their involvement in prayer, reading a book of scriptures, and attendance at a house of worship. Ideological religiosity involves the degree to which people accept religious doctrine and includes the nature of their belief in a deity, while intellectual religiosity concerns the extent of their knowledge of their religion’s history and teachings. Finally, consequential religiosity refers to the extent to which religion affects their daily behavior.

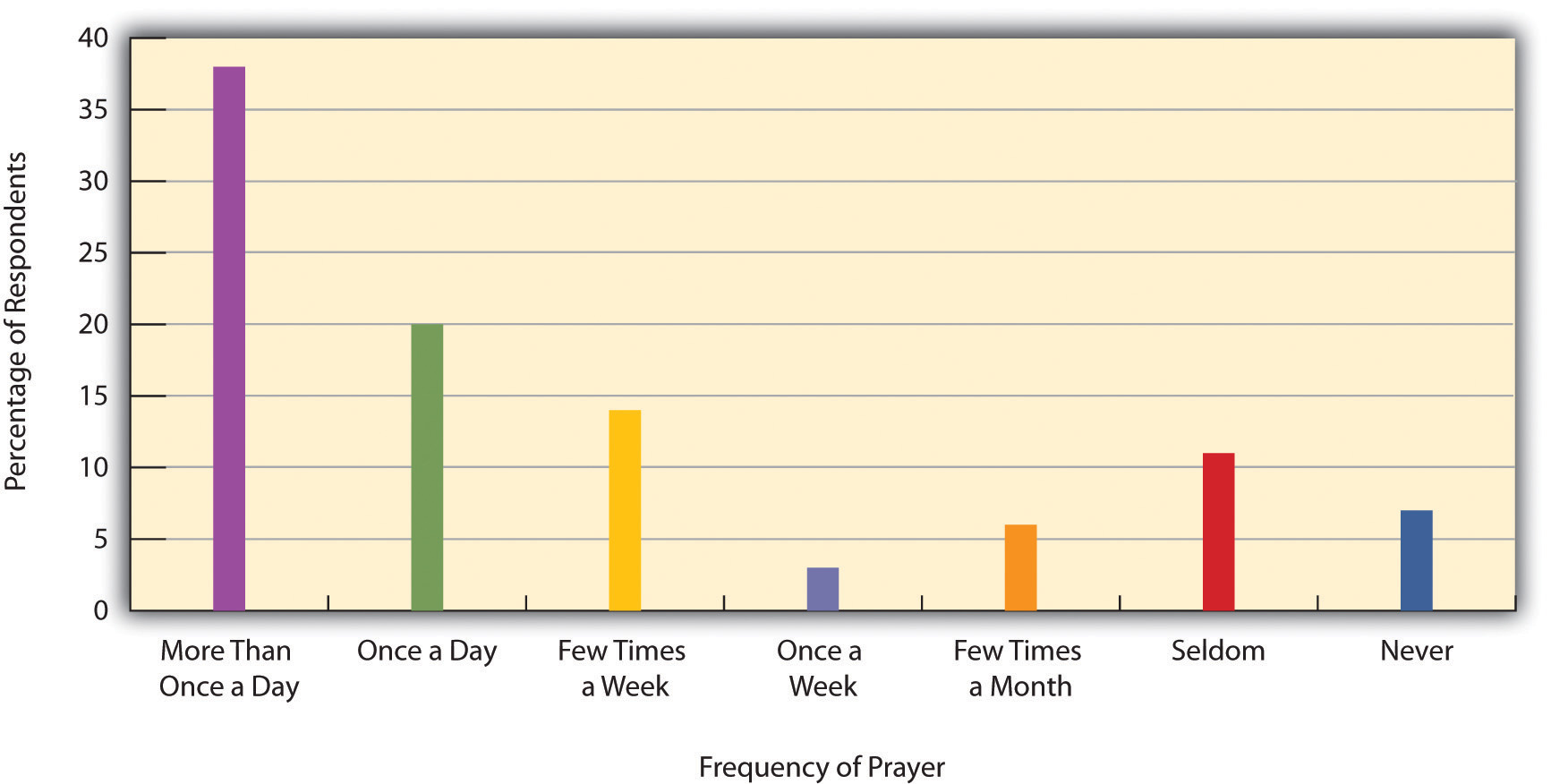

National data on prayer are perhaps especially interesting (see Figure "Frequency of Prayer"), as prayer occurs both with others and by oneself. Almost 60% of Americans say they pray at least once daily outside religious services, and only 7% say they never pray (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2008).Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2008). U.S. religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Women are more likely than men to pray daily: 66% of women say they pray daily, versus only 49% of men. Daily praying is also more common among older people than younger people, among African Americans than whites, and among people without a college degree than those with a college degree. As these demographic differences indicate, the social backgrounds of Americans affect this important dimension of their religiosity.

Key Takeaways

- The United States is a fairly religious nation, with most people expressing a religious preference. About half of Americans are Protestants, and one-fourth are Catholics.

- Religiosity is composed of several dimensions. Almost 60% of Americans say they pray at least once daily outside religious services.

- Generally speaking, higher levels of religiosity are associated with more conservative views on social, moral, and political issues; with lower rates of deviant behavior; and with greater psychological and physical well-being.