1.3: Important Individuals

- Page ID

- 1996

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Would you rather live in a society with strict laws and punishments or one in which the people could do anything they wanted with no laws or consequences? Explain your answer.

Before continuing any further in this section, watch the video lecture below for a better understanding of why many political philosophers throughout history have proposed and explained the necessity of a formal government.

Whenever people come together, it becomes necessary to ensure that they can safely and effectively relate to each other in a civil way. People must be able to collectively solve important problems and determine the rules and standards by which they will live. These become the main reasons that governments are necessary. To quote James Madison, “If men were angels, governments would not be necessary” (Federalist 51).

Many times throughout history, it became necessary for the leader of a society to mandate a standard for the behavior of his or her people and to ensure those standards were followed by applying harsh consequences for disregard.

History is full of examples where it became necessary to institute rules by which a society will live. For example, in 1754 BC, Hammurabi, a famous Babylonian King, wrote down a series of laws and punishments on ancient clay tablets. He based these on the principle of “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth." Today, these laws are known as the Code of Hammurabi. Later, Moses, a biblical prophet from the Old Testament, received a series of laws to be delivered to the Hebrew nation. Today, these laws are known as “The Ten Commandments.”

Early Laws

|

Hammurabi – “Hammurabi’s Code” |

Moses-Ten Commandments |

|

195. If a son strike[s] his father, his hands shall be cut off. 196. If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out. 198. If he put out the eye of a freed man, or break the bone of a freed man, he shall pay one gold mina. 199. If he put out the eye of a man's slave, or break the bone of a man's slave, he shall pay one-half of its value. 200. If a man knock out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out. 131. If a man bring a charge against one's wife, but she is not surprised with another man, she must take an oath and then may return to her house. 132. If the "finger is pointed" at a man's wife about another man, but she is not caught sleeping with the other man, she shall jump into the river for her husband. 8. If anyone steal cattle or sheep, or an ass, or a pig or a goat, if it belong to a god or to the court, the thief shall pay thirtyfold therefor; if they belonged to a freed man of the king he shall pay tenfold; if the thief has nothing with which to pay he shall be put to death. 1. If anyone ensnare another, putting a ban upon him, but he can not prove it, then he that ensnared him shall be put to death. |

1. Thou shalt have no other gods before me. 2. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 3. Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain 4. Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. 5. Honor thy father and thy mother: 6. Thou shalt not kill. 7. Thou shalt not commit adultery. 8. Thou shalt not steal. 9. Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor. 10. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbor’s.Exodus 20:1-17; Deuteronomy 5:4-21 |

The Rule of Law

Both Hammurabi's Code and the Ten Commandments are sets of laws that are handed down with very little say from the people themselves. When people decide upon their own rules and standards of behavior in a collective manner and live according to those rules, they are abiding by the Rule of Law. This means that the people decide for themselves which laws are made, how they will be followed, and what consequences will be enforced if they are not.

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu

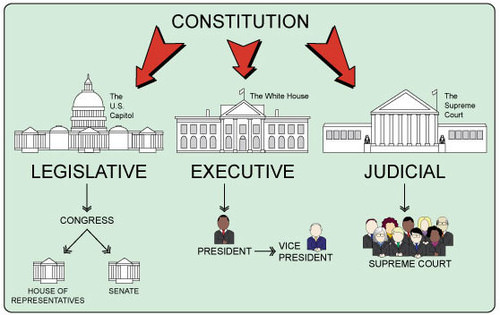

Simply called Montesquieu, the noted political philosopher was also a French judge and man of letters, which meant he could read and write--something of a rarity for the time period of the early 1700s. Montesquieu expressed the idea of separation of powers, which is implemented in many constitutions across the world.

He anonymously published The Spirit of the Laws in 1748. This text stated that in order for political institutions to be successful, it was necessary for them to reflect the social and geographical aspects of the particular community.

Montesquieu pleaded for a constitutional system of government with separation of powers, the preservation of legality and civil liberties, and the end of slavery.

This discourse greatly influenced the Founding Fathers in drafting the United States Constitution.

Sir William Blackstone

One proponent of this philosophy of the Rule of Law was Sir William Blackstone. He developed the ideas of British Common Law and such principles as presumed innocence (innocent until proven guilty), so that laws could be fairly and equitably applied across society. Blackstone's most famous quote was, "Better ten guilty men escape than one innocent man suffer." This quote would later be called "Blackstone's Formulation." Blackstone's focus on the Rule of Law and his contributions to legal education and thought would become a cornerstone of the American government.

William Blackstone (1723-1780) was an English-born jurist who greatly influenced the legal system of Great Britain and the United States. He was educated at Oxford with studies in the classics, math, and logic. He was further educated in law and admitted to the bar in 1746. He worked as a lawyer, served as a judge, and later became a lecturer at Oxford University where his series of lectures became the basis for his book Commentaries of the Laws of England. It was published in February 1766 (later to be augmented and further revised).

The Commentaries

Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England was the first attempt at collecting and organizing English Common Law. This book would give substance to English Common Law. It was written in a way that even a novice law student could understand its concepts. It became the basis for the study of law in the 18th and 19th centuries in most English-speaking nations. There was such a high demand it was reprinted many times and translated into many languages.

Influence on American Government

One important aspect of Commentaries... for the late 18th- and early 19th-century Americans was its convenience. It was published at a time when law books were scarce and expensive. With this one publication, a lawyer could essentially have a complete law library in four volumes. It was so much easier to transport a compendium of legal knowledge in a convenient collection.

Blackstone wrote, "Christianity is part of the law of England," but he also wrote that the law of England, "Gives liberty, rightly understood, that is, protection to a Jew, Turk, or heathen as well as to those who profess the true religion of Christ."

Thomas Jefferson put several phrases in the Declaration of Independence that can be directly attributed to Blackstone including: "self-evident," "unalienable rights," and "Laws of Nature," and Nature's God."

John Marshall, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, quoted Blackstone's definition of writ of mandamus (a legal order to a state to perform an action) in Marbury vs. Madison (1803), which established the important concept of judicial review. Judicial review gives the courts the power to overturn a law on the basis of its constitutionality.

Marshall also cited Blackstone in his decision in the trial of Aaron Burr. Blackstone was cited at the Constitutional Convention, particularly in regard to ex post facto laws (laws that retroactively make a crime from an act that was not criminal at the time it was committed), which Blackstone determined only applied to criminal cases.

Alexander also quoted Blackstone in Federalist 69 and 84, while Patrick Henry used Blackstone to support his opposition to Virginia's adoption of the Constitution because there was no provision for a jury trial in civil cases included in that document. Abraham Lincoln read and studied Blackstone as part of his self-taught legal education.

Republicanism

A political philosophy that has been a major part of American civic thought since its founding is called Republicanism. This concept values liberty and unalienable rights as central values, making people sovereign as a whole. Republicanism rejects monarchy, aristocracy and inherited political power, expects citizens to be virtuous and faithful in their performance of civic duties, and vilifies corruption. American republicanism was first expressed and first practiced by the Founding Fathers.

Today

Blackstone became less influential after the Civil War. Some objected to his support of the monarchy, and others would attribute the decline in his influence to the more structured legal education, which replaced the text method (his 'Commentary') with the case method of study. However, it is clear that Blackstone's ideas were critical in defining and applying the Rule of Law to legal systems around the world, particularly in Great Britain and the United States.

Law and Religion: Should they Co-Exist?

The United States has a history of a "wall of separation" between church and state. In the modern era that wall is beginning to erode

Video: The Objective Standard by Which to Judge Laws

Government is the institutions who have authority to make and carry out laws, decisions, and actions on behalf of the citizens of a nation or territory.

Government and Politics: What's the Difference?

Governments can best be described as institutions, which have recognized authority to make and carry out laws, decisions, and actions on behalf of the citizens of a nation or territory. As we will see later, there are many types and forms of government; however, they all have this definition in common.

States

States are contiguous geographic regions whose laws and policies are created and enforced by a recognized government. All states have four general characteristics:

First, they must have a population. However, the size of that population has nothing to do with whether a geographic region is recognized as a state.

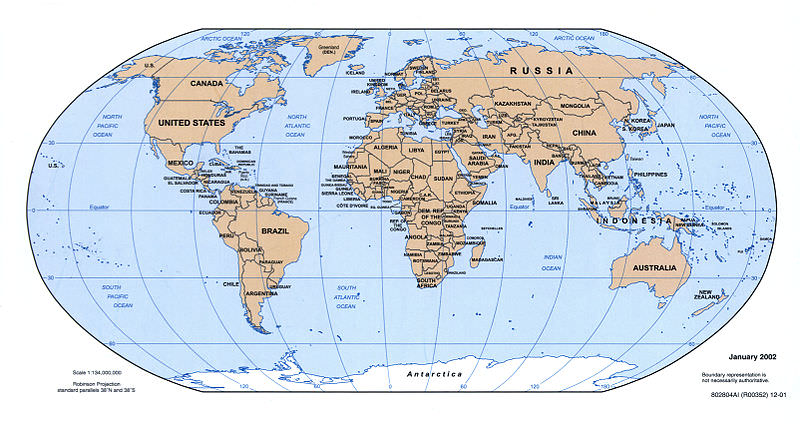

Second, they must have known and recognized boundaries (as in the political map above).

Third, they must have sovereignty, meaning they must decide their own foreign and domestic policies without seeking the direct authority of any other nation. For instance, the State of Texas is not a sovereign nation as it must still abide by the laws and constitution of the United States.

Fourth, states must have a government, which consists of the institutions and people who have recognized authority to create and execute laws and make decisions on behalf of the citizens.

Politics

Politics can best be described as the processes used to acquire and exercise authority. Harold Lasswell (1950) is most often credited as creating the best definition of politics. He said that politics was all about acquiring and using power. His definition was simply, “who gets what, when, and how.”

While government and politics are two very different things, they are often misunderstood by citizens who mistake government for politics. Quite simply, governments are institutions for laws and those who create them, while politics is best described as the processes by which those institutions are created, lawmakers are selected, and decisions are made and implemented.

Source: Lasswell, Harold, Politics: Who Gets What, When and How, ©1950, New York, Peter Smith Video: The Difference Between Government and Politics

Video Discussion Questions

After viewing the video above, answer the following questions.

1. How does the subject of the video describe the difference between government and politics?

2. In what context was this video made and presented? How does this impact your perception of the subject's credibility (believability) as a presenter?

3. Do you agree or disagree with the ideas presented in the video? Why/why not?

Study/Discussion Questions

For each of the following terms, write a sentence which uses or describes the term in your own words.

|

William Blackstone |

Moses |

Politics |

|

Government |

Natural Law |

Rule of Law |

|

Hammurabi |

Montesquieu |

States |

1. What did James Monroe mean when he said, “If men were angels, governments would not be necessary”?

2. What did the law codes or Hammurabi and Moses have in common? How were they different

3. What was Blackstone's formulation? How is it applied in our system of government today?

4. What two laws did Blackstone see as often being in conflict with each other? Of the two, which did Blackstone see as superior?

5. What is the difference between government and politics? Support your answer with examples.

6. From your experience, are people who represent government more concerned with government or with politics? Explain your answer.

7. What are the four general characteristics of a state?

8. How did Harold Lasswell describe politics? Explain what is meant by his definition.

9. Give an example from your life of an encounter with government.

10. Give an example from your life of an encounter with politics.