4.8: Court Cases that Interpret Guaranteed Rights

- Page ID

- 5852

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)According to Article III of The Constitution, the federal judicial system was established. Section I further states, "The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish." By hearing important cases and making landmark decisions, the Supreme Court's rulings have paved the way for individual civil liberties and civil rights to remain intact. Some of the following cases set legal precedents that changed the way laws were enforced.

Landmark Cases in Civil Liberties and Civil Rights

Engel v. Vitale (1962)

Facts of the Case

The Board of Regents for the State of New York authorized a short, voluntary prayer for recitation at the start of each school day. This was an attempt to defuse the politically potent issue by taking it out of the hands of local communities. The blandest of invocations read as follows: "Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and beg Thy blessings upon us, our teachers, and our country."

Question

Does the reading of a nondenominational prayer at the start of the school day violate the "establishment of religion" clause of the First Amendment?

Conclusion

Decision: 6 votes for Engel, 1 vote(s) against

Legal provision: Establishment of Religion

Yes. Neither the prayer's nondenominational character nor its voluntary character saves it from unconstitutionality. By providing the prayer, New York officially approved religion. This was the first in a series of cases in which the Court used the establishment clause to eliminate religious activities of all sorts, which had traditionally been a part of public ceremonies. Despite the passage of time, the decision is still unpopular with a majority of Americans.

Importance

Prohibited organized prayer in public schools and has become an important linchpin in the current “separation of church and state” policies. This remains a hotly debated topic with extreme divisiveness and disagreement on both sides of the debate. Ultimately, this case created a clear boundary between the business of government and the institution/endorsement of religious practices in public institutions (primarily public schools but extended to other government institutions at the federal, state, and local level as well)

Gideon v. Wainwright (1963)

Facts of the Case

Clarence Earl Gideon was charged in a Florida state court with a felony: having broken into and entered a poolroom with the intent to commit a misdemeanor offense. When he appeared in court without a lawyer, Gideon requested that the court appoint one for him. According to Florida state law, however, an attorney may only be appointed to an indigent defendant in capital cases, so the trial court did not appoint one. Gideon represented himself in trial. He was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison. Gideon filed a habeas corpus petition in the Florida Supreme Court and argued that the trial court’s decision violated his constitutional right to be represented by counsel. The Florida Supreme Court denied habeas corpus relief.

Question

Does the Sixth Amendment's right to counsel in criminal cases extend to felony defendants in state courts?

Conclusion

Decision: 9 votes for Gideon, 0 vote(s) against

Legal provision: Right to Counsel

Yes. Justice Hugo L. Black delivered the opinion of the 9-0 majority. The Supreme Court held that the framers of the Constitution placed a high value on the right of the accused to have the means to put up a proper defense, and the state, as well as federal courts, must respect that right. The Court held that it was consistent with the Constitution to require state courts to appoint attorneys for defendants who could not afford to retain counsel on their own.

Justice William O. Douglas wrote a concurring opinion in which he argued that the Fourteenth Amendment does not apply a watered-down version of the Bill of Rights to the states. Since constitutional questions are always open for consideration by the Supreme Court, there is no need to assert a rule about the relationship between the 14th Amendment and the Bill of Rights. In his separate opinion concurring in the judgment, Justice Tom C. Clark wrote that the Constitution guarantees the right to counsel as a protection of due process, and there is no reason to apply that protection in certain cases but not others. Justice John M. Harlan wrote a separate concurring opinion in which he argued that the majority’s decision represented an extension of earlier precedent that established the existence of a serious criminal charge to be a “special circumstance” that requires the appointment of counsel. He also argued that the majority’s opinion recognized a right to be valid in state courts as well as federal ones; it did not apply a vast body of federal law to the states.

Importance

The Court used the 14th Amendment to justify requiring the states to provide anyone accused of a crime with an attorney at no charge. Defendants could no longer be required to defend themselves if they do not have the capacity to pay. The Court justified its decision with the argument that the right to counsel was essential for a fair trial. In later cases, this ruling was extended to cover any crime with potential jail time (misdemeanor or felony).

Hernandez v. Texas (1953)

Facts of the Case

Pete Hernandez, an agricultural worker, was indicted for the murder of Joe Espinoza by an all-Anglo (white) grand jury in Jackson County, Texas. Claiming that Mexican-Americans were barred from the jury commission that selected juries, and from petit juries, Hernandez' attorneys tried to quash the indictment. Moreover, Hernandez tried to quash the petit jury panel called for service because persons of Mexican descent were excluded from jury service in this case. A Mexican-American had not served on a jury in Jackson County in over 25 years and thus, Hernandez claimed that Mexican ancestry citizens were discriminated against as a special class in Jackson County. The trial court denied the motions. Hernandez was found guilty of murder and sentenced by the all-Anglo jury to life in prison. In affirming, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found that "Mexicans are...members of and within the classification of the white race as distinguished from members of the Negro Race" and rejected the petitioners' argument that they were a "special class" under the meaning of the 14th Amendment. Further, the court pointed out that "so far as we are advised, no member of the Mexican nationality" challenged this classification as white or Caucasian.

Question

Is it a denial of the 14th Amendment equal protection clause to try a defendant of a particular race or ethnicity before a jury where all persons of his race or ancestry have, because of that race or ethnicity, been excluded by the state?

Conclusion

Decision: 9 votes for Hernandez, 0 vote(s) against

Legal provision: Equal Protection

Yes. In a unanimous opinion delivered by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment protects those beyond the two classes of white or Negro, and extends to other racial groups in communities depending upon whether it can be factually established that such a group exists within a community. In reversing, the Court concluded that the Fourteenth Amendment "is not directed solely against discrimination due to a 'two-class theory'" but in this case covers those of Mexican ancestry. This was established by the fact that the distinction between whites and Mexican ancestry individuals was made clear at the Jackson County Courthouse itself where "there were two men's toilets, one unmarked, and the other marked 'Colored Men and 'Hombres Aqui' ('Men Here')," and by the fact that no Mexican ancestry person had served on a jury in 25 years. Mexican Americans were a "special class" entitled to equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Importance

Held that Hispanics must be considered a “class of their own” and were entitled to equal protection and civil rights recognition.

Mapp v. Ohio (1961)

Facts of the Case

Dollree Mapp was convicted of possessing obscene materials after an admittedly illegal police search of her home for a fugitive. She appealed her conviction on the basis of freedom of expression.

Question

Were the confiscated materials protected by the First Amendment? (May evidence obtained through a search in violation of the Fourth Amendment be admitted in a state criminal proceeding?)

Conclusion

Decision: 6 votes for Mapp, 3 vote(s) against

Legal provision: Amendment 4: Fourth Amendment

The Court brushed aside the First Amendment issue and declared that "all evidence obtained by searches and seizures in violation of the Constitution is, by [the Fourth Amendment], inadmissible in a state court." Mapp had been convicted on the basis of illegally obtained evidence. This was an historic -- and controversial -- decision. It placed the requirement of excluding illegally obtained evidence from the court at all levels of the government. The decision launched the Court on a troubled course of determining how and when to apply the exclusionary rule.

Importance

The Court declared that evidence discovered in the process of an illegal search could not be used in a state court case. This has become known as the “fruit of the poisonous tree” principle.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

Facts of the Case

The Court was called upon to consider the constitutionality of a number of instances, ruled on jointly, in which defendants were questioned "while in custody or otherwise deprived of [their] freedom in any significant way." In Vignera v. New York, the petitioner was questioned by police, made oral admissions, and signed an inculpatory statement all without being notified of his right to counsel. Similarly, in Westover v. United States, the petitioner was arrested by the FBI, interrogated, and made to sign statements without being notified of his right to counsel. Lastly, in California v. Stewart, local police held and interrogated the defendant for five days without notification of his right to counsel. In all these cases, suspects were questioned by police officers, detectives, or prosecuting attorneys in rooms that cut them off from the outside world. In none of the cases were suspects given warnings of their rights at the outset of their interrogation.

Question

Does the police practice of interrogating individuals without notifying them of their right to counsel and their protection against self-incrimination violate the Fifth Amendment?

Conclusion

Decision: 5 votes for Miranda, 4 vote(s) against

Legal provision: Self-Incrimination

The Court held that prosecutors could not use statements stemming from custodial interrogation of defendants unless they demonstrated the use of procedural safeguards "effective to secure the privilege against self- incrimination." The Court noted that "the modern practice of in-custody interrogation is psychologically rather than physically oriented" and that "the blood of the accused is not the only hallmark of an unconstitutional inquisition." The Court specifically outlined the necessary aspects of police warnings to suspects, including warnings of the right to remain silent and the right to have counsel present during interrogations.

Importance

In a 5-4 vote, the Court agreed that Miranda’s rights had been violated and ordered his conviction struck down. Today, the issues of due process and the rights of those accused of a crime are still of great importance. While some may argue that protecting individual rights of accused persons places an undue burden on the victims of crimes and makes it harder for the state to get a conviction there are those who also argue that having too few protections for the accused would result in abuses of power. They fear that innocent people might be subject to coercion through violence resulting in false confessions. The courts are required to balance the rights of those who are accused of crimes with the rights and protections that society must afford to those who would be the victim of a crime. We see this decision on every “cop show” and in the news when people are arrested or interrogated and are read the famous “Miranda Warning.”

Example Miranda Warning:

You have the right to remain silent when questioned. Anything you say or do may be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to consult an attorney before speaking to the police and to have an attorney present during questioning now or in the future. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you before any questioning, if you wish. If you decide to answer any questions now, without an attorney present, you will still have the right to stop answering at any time until you talk to an attorney. Knowing and understanding your rights as I have explained them to you, are you willing to answer my questions without an attorney present?

Video: Miranda Warning 40 Years Later

Roe V. Wade (1973)

Facts of the Case

Roe, a Texas resident, sought to terminate her pregnancy by abortion. Texas law prohibited abortions except to save the pregnant woman's life. After granting certiorari, the Court heard arguments twice. The first time, Roe's attorney--Sarah Weddington--could not locate the constitutional hook of her argument for Justice Potter Stewart. Her opponent--Jay Floyd--misfired from the start. Weddington sharpened her constitutional argument in the second round. Her new opponent -- Robert Flowers -- came under strong questioning from Justices Potter Stewart and Thurgood Marshall.

Question

Does the Constitution embrace a woman's right to terminate her pregnancy by abortion?

Conclusion

Decision: 7 votes for Roe, 2 vote(s) against

Legal provision: Due Process

The Court held that a woman's right to an abortion fell within the right to privacy (recognized in Griswold v. Connecticut) protected by the 14th Amendment. The decision gave a woman total autonomy over the pregnancy during the first trimester and defined different levels of state interest for the second and third trimesters. As a result, the laws of 46 states were affected by the Court's ruling.

Importance

Established a woman’s right to an abortion as part of a constitutional right to privacy using the 9th Amendment and 14th Amendment as its basis. This case has become one of the most controversial modern Supreme Court decisions. Since the Court’s ruling in 1973, this case has been the center of a divisive fight between “pro-choice” and “pro-life” sides of a social and legal debate.

Schenck v. United States (1919)

Facts of the Case

During World War I, Schenck mailed circulars to draftees. The circulars suggested that the draft was a monstrous wrong motivated by the capitalist system. The circulars urged "Do not submit to intimidation" but advised only peaceful action such as petitioning to repeal the Conscription Act. Schenck was charged with conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act by attempting to cause insubordination in the military and to obstruct recruitment.

Question

Are Schenck's actions (words, expression) protected by the free speech clause of the First Amendment?

Conclusion

Decision: 9 votes for United States, 0 vote(s) against

Legal provision: 1917 Espionage Act; US Constitution Amendment 1

Holmes, speaking for a unanimous Court, concluded that Schenck is not protected in this situation. The character of every act depends on the circumstances. "The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent." During wartime, utterances tolerable in peacetime can be punished.

Importance

This decision limited First Amendment right to free speech if it imposes a “clear and present danger” to the security of the United States or its people.

Texas v. Johnson (1989)

Facts of the Case

In 1984, in front of the Dallas City Hall, Gregory Lee Johnson burned an American flag as a means of protest against Reagan administration policies. Johnson was tried and convicted under a Texas law outlawing flag desecration. He was sentenced to one year in jail and assessed a $2,000 fine. After the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed the conviction, the case went to the Supreme Court.

Question

Is the desecration of an American flag, by burning or otherwise, a form of speech that is protected under the First Amendment?

Conclusion

Decision: 5 votes for Johnson, 4 vote(s) against

Legal provision: Amendment 1: Speech, Press, and Assembly

In a 5-to-4 decision, the Court held that Johnson's burning of a flag was protected expression under the First Amendment. The Court found that Johnson's actions fell into the category of expressive conduct and had a distinctively political nature. The fact that an audience takes offense to certain ideas or expression, the Court found, does not justify prohibitions of speech. The Court also held that state officials did not have the authority to designate symbols to be used to communicate only limited sets of messages, noting that "[i]f there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the Government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable."

Importance

This case answered the question of whether or not the First Amendment protects the burning of the United States flag as a form of symbolic speech with a definitive “YES!” In response, there has been a constant push in many states (particularly more conservative states in the South and Midwest) for a Constitutional Amendment that would prohibit the burning of the United States Flag.

Video: Should Flag Burning be Illegal?

Other Important Cases:

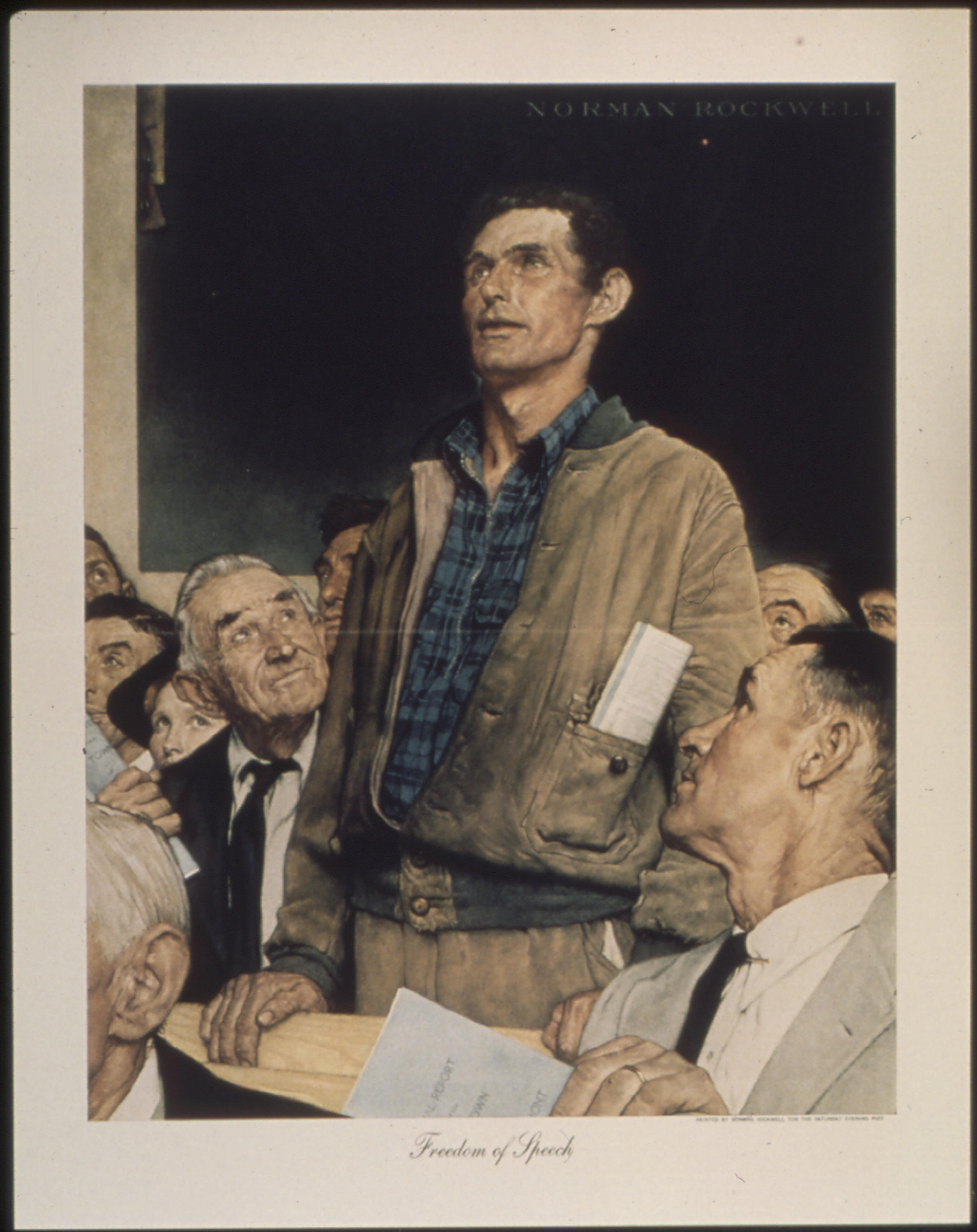

Overview: First Amendment to the United States Constitution

First Amendment Rights

Overview: Freedom of religion in the United States

Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1879) Religious belief or duty cannot be used as a defense against a criminal indictment.

Davis v. Beason, 133 U.S. 333 (1890) The Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act of 1882 does not violate the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment even though polygamy is part of several religious beliefs.

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940) The states cannot interfere with the free exercise of religion.

Minersville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U.S. 586 (1940) The First Amendment does not require public schools to excuse students from saluting the American flag and reciting the Pledge of Allegiance on religious grounds. (Overruled by West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943))

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105 (1943) A Pennsylvania ordinance that imposes a license tax on those selling religious merchandise violates the Free Exercise Clause.

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943) Public schools cannot override the religious beliefs of their students by forcing them to salute the American flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance.

Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947) A state law that reimburses the costs of transportation to and from parochial schools does not violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The Establishment Clause is incorporated against the states, and the Constitution requires a sharp separation between government and religion.

McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 (1948) The use of public school facilities by religious organizations to give religious instruction to school children violates the Establishment Clause.

Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963) School-sponsored reading of the Bible and recitation of the Lord's Prayer in public schools is unconstitutional under the Establishment Clause.

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968) Taxpayers have the standing to sue to prevent the disbursement of federal funds in contravention of the specific constitutional prohibition against government support of religion.

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971) For a law to be considered constitutional under the Establishment Clause, the law must have a legitimate secular purpose, must not have the primary effect of either advancing or inhibiting religion, and must not result in an excessive entanglement of government and religion.

Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972) Parents may remove their children from public schools for religious reasons.

Marsh v. Chambers, 463 U.S. 783 (1983) A state legislature's practice of opening its sessions with a prayer offered by a state-supported chaplain does not violate the Establishment Clause.

Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (1987) Teaching creationism in public schools is unconstitutional.

Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990) Neutral laws of general applicability do not violate the Free Exercise Clause.

Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. 577 (1992) Including a clergy-led prayer within the events of a public school graduation ceremony violates the Establishment Clause.

Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520 (1993) The government must show a compelling interest to pass a law that targets a religion's ritual (as opposed to a law that happens to burden the ritual but is not directed at it). Failing to show such an interest, the prohibition of animal sacrifice is a violation of the Free Exercise Clause.

Rosenberger v. University of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995) A university cannot use student dues to fund secular groups while excluding religious groups.

Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203 (1997) Allowing public school teachers to teach at parochial schools does not violate the Establishment Clause as long as the material that is taught is secular and neutral in nature and no "excessive entanglement" between government and religion is apparent.

Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, 530 U.S. 290 (2000) Prayer in public schools that is initiated and led by students violates the Establishment Clause.

Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639 (2002) A government program that provides tuition vouchers for students to attend a private or religious school of their parents' choosing is constitutional because the vouchers are neutral toward religion and, therefore, do not violate the Establishment Clause.

Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 400 F. Supp. 2d 707 (M.D. Pa. 2005) Teaching intelligent design in public school biology classes violates the Establishment Clause because intelligent design is not science, and it "cannot uncouple itself from its creationist, and thus religious, antecedents."

Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 565 U.S. (2012) Ministers cannot sue their churches by claiming termination in violation of employment non-discrimination laws. The Establishment Clause forbids the appointing of ministers by the government; therefore, it cannot interfere with the freedom of religious groups to select their own ministers under the Free Exercise Clause.

Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U.S. (2014) A town council's practice of opening its sessions with a sectarian prayer does not violate the Establishment Clause.

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. (2014) Closely held, for-profit corporations have free exercise rights under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. As applied to such corporations, the requirement of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act that employers provide their female employees with no-cost access to contraception violates the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

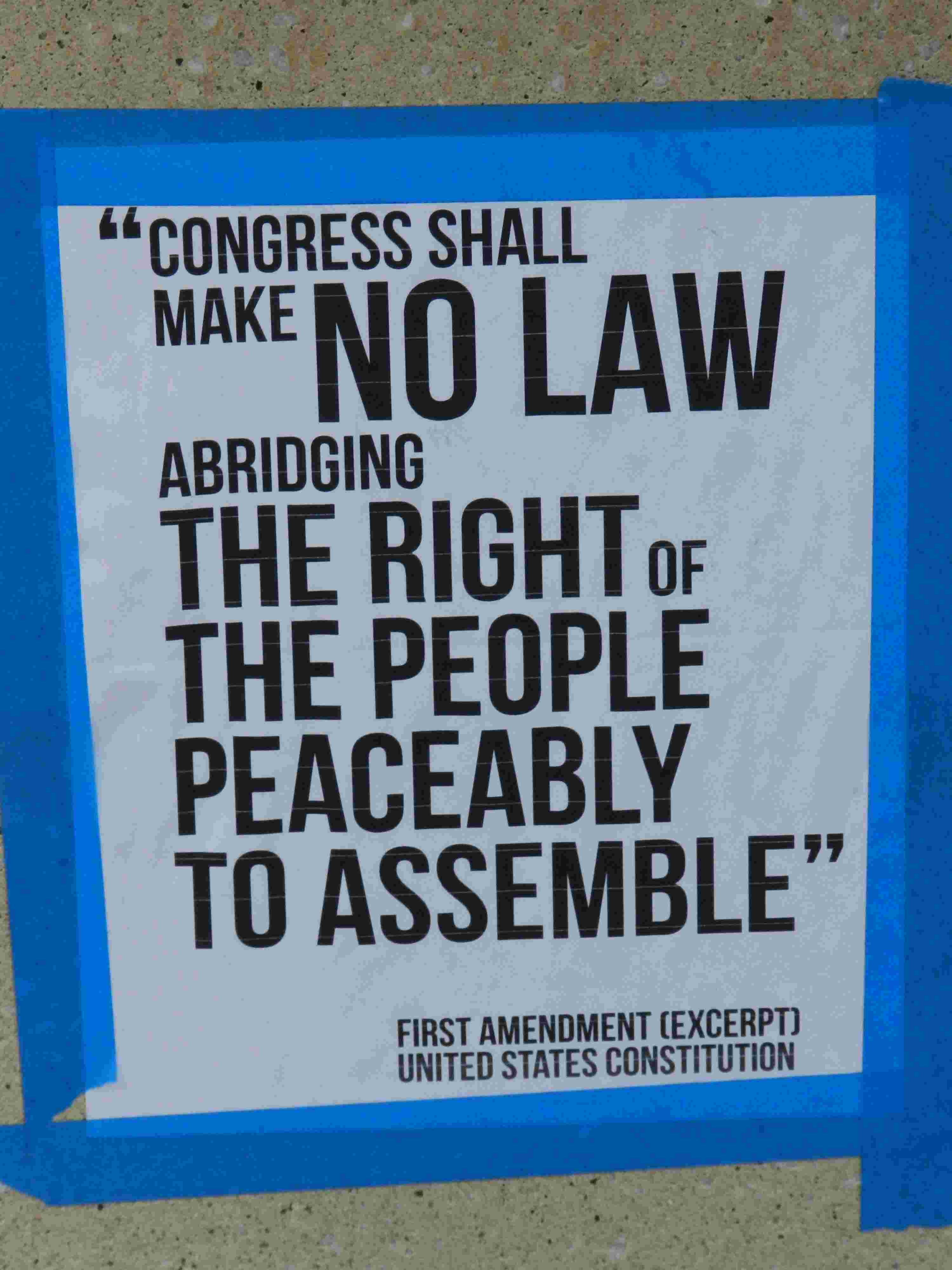

Freedom of Speech and Freedom of the Press

Main articles: Freedom of speech in the United States and Freedom of the press in the United States

Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, 236 U.S. 230 (1915) Motion pictures are not entitled to free speech protection because they are a business, not a form of art. (Overruled by Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson (1952))

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925) The provisions of the First Amendment that protect the freedom of speech and the freedom of the press apply to the governments of the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931) A California law that bans red flags is unconstitutional because it violates the First Amendment's protection of symbolic speech as applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment.

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931) A Minnesota law that imposes prior restraints on the publication of "malicious, scandalous, and defamatory" content violates the First Amendment as applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment.

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942) Fighting words—words that by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace—are not protected by the First Amendment.

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1952) Motion pictures, as a form of artistic expression, are protected by the First Amendment.

Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957) Obscene material is not protected by the First Amendment. (Superseded by Miller v. California (1973))

One, Inc. v. Olesen, 355 U.S. 371 (1958) Pro-homosexual writing is not per se obscene.

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) Public officials, to prove they were libeled, must show not only that a statement is false, but also that it was published with malicious intent.

Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 (1967) News organizations may be liable when printing allegations about public figures if the information they disseminate is recklessly gathered and unchecked.

United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968) A criminal prohibition against draft-card burning does not violate the First Amendment because its effect on speech is only incidental, and it is justified by the significant governmental interest in maintaining an efficient and effective military draft system.

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969) Wearing armbands as a form of protest on public school grounds is protected by the First Amendment.

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969) The mere advocacy of the use of force or of violation of the law is protected by the First Amendment. Only inciting others to take direct and immediate unlawful action is without constitutional protection.

Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971) The First Amendment prohibits the states from making the public display of a single four-letter expletive a criminal offense without a more specific and compelling reason than a general tendency to disturb the peace.

New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971) The federal government's desire to keep the Pentagon Papers classified is not strong enough to justify violating the First Amendment by imposing prior restraints on the material.

Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973) To be obscene, a work must fail the Miller test, which determines if it has any "serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value."

Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323 (1974) The First Amendment permits the states to formulate their own standards of liability for defamation against private individuals as long as liability is not imposed without fault. If the state standard is lower than actual malice, then only actual damages may be awarded.

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976) Spending money to influence elections is a form of constitutionally protected free speech; therefore, federal limits on campaign contributions are constitutional in only a limited number of circumstances.

Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation, 438 U.S. 726 (1978) Broadcasting has less First Amendment protection than other forms of communication because of its pervasive nature. The Federal Communications Commission has broad authority to determine what constitutes indecency in different contexts.

New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747 (1982) Laws that prohibit the sale, distribution, and advertisement of child pornography are constitutional even if the content does not meet the conditions necessary for it to be labeled obscene.

Bethel School District v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986) The First Amendment permits a public school to punish a student for giving a lewd and indecent speech at a school assembly even if the speech is not obscene.

Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988) Public school curricular student newspapers that have not been established as forums for student expression are subject to a lower level of First Amendment protection than independent student expression or newspapers established by policy or practice as forums for student expression.

Hustler Magazine v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988) Parodies of public figures, including those intended to cause emotional distress, are protected by the First Amendment.

Barnes v. Glen Theatre, Inc., 501 U.S. 560 (1991) While nude dancing is a form of expressive conduct, public indecency laws regulating or prohibiting nude dancing are constitutional because they further substantial governmental interests in maintaining order and protecting morality.

Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844 (1997) The Communications Decency Act, which regulates certain content on the Internet, is so overbroad that it is an unconstitutional restraint on the First Amendment.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) Limits on corporate and union political expenditures during election cycles violate the First Amendment. Corporations and labor unions can spend unlimited sums in support of or in opposition to candidates as long as the spending is independent of the candidates.

Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. (2011) The infamous Westboro Baptist Church's picketing of funerals cannot be liable for a tort of emotional distress.

Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, 564 U.S. (2011) Video games are a distinct communications medium protected by the First Amendment.

McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, 572 U.S. (2014) Limits on the total amounts of money that individuals can donate to political campaigns during two-year election cycles violate the First Amendment.

Freedom of Association

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958) The freedom to associate with organizations dedicated to the "advancement of beliefs and ideas" is an inseparable part of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, 515 U.S. 557 (1995) Private citizens organizing a public demonstration have the right to exclude groups whose message they disagree with from participating.

Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000) Private organizations are allowed to choose their own membership and expel members based on their sexual orientation even if such discrimination would otherwise be prohibited by anti-discrimination legislation designed to protect minorities in public accommodations.

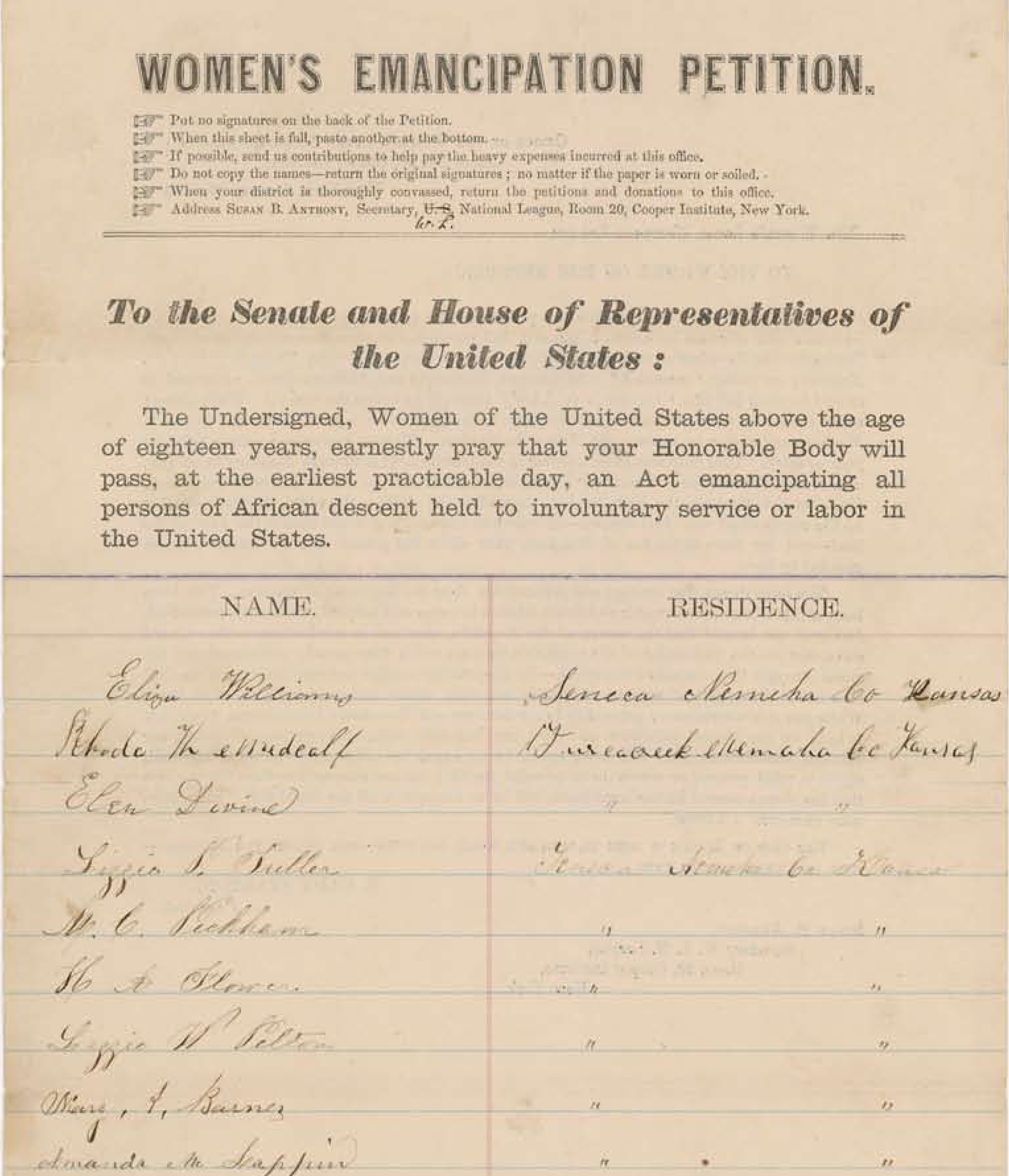

Freedom to Petition

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963) The Free Petition Clause extends to the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

California Motor Transport Co. v. Trucking Unlimited, 404 U.S. 508 (1972) The Free Petition Clause encompasses petitions to all three branches of the federal government—the Congress, the executive including administrative agencies and the judiciary.

Second Amendment Rights

Overview: Second Amendment to the United States Constitution

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876) The Second Amendment has no purpose other than to restrict the powers of the federal government. It does not specifically grant private citizens the right to keep and bear arms because that right exists independent of the Constitution.

Presser v. Illinois, 116 U.S. 252 (1886) An Illinois law that prohibits common citizens from forming personal military organizations, performing drills, and parading is constitutional because such a law does not limit the personal right to keep and bear arms.

United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939) The federal government and the states can limit access to all weapons that do not have "some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well-regulated militia."

District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008) The Second Amendment protects an individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia and to use it for traditionally lawful purposes such as self-defense within the home.

McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 3025 (2010) The individual right to keep and bear arms for self-defense is fully applicable to the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Study/Discussion Questions

1. Complete the table to detail why each case was so important.

| case | Importance |

|---|---|

| Engel v. Vitale | |

| Schenck v. U.S. | |

| Texas v. Johnson | |

| Miranda v. Arizona | |

| Gideon v. Wainwright | |

| Mapp v. Ohio | |

| Roe v. Wade |

2. Do you think a federal ruling on a landmark case may set a bad precedent? Explain using a case as proof of your opinion.