6.2: Impact of Political Changes

- Page ID

- 2012

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Communication is a central activity of everyone engaged in politics—people asserting, arguing, deliberating, and contacting public officials; candidates seeking to win votes; lobbyists pressuring policymakers; presidents appealing to the public, cajoling Congress, addressing the leaders and people of other countries. All this communication sparks more communication, actions, and reactions.

The bulk of information that Americans obtain about politics and government comes through the mass and new media. Mass media are well-established communication formats, such as newspapers and magazines, network television and radio stations, designed to reach large audiences. Mass media also encompass entertainment fares, such as studio films, best-selling books, and hit music.

Media Informs the Public

New media are forms of electronic communication made possible by computer and digital technologies. They include the Internet, digital video cameras, cellular telephones, and cable and satellite television and radio. This media provides quick, interactive, targeted, and potentially democratic communication, such as social media, blogs, podcasts, websites, wikis, instant messaging, and e-mail.

The media, old and new, are central to American politics and government in three ways. First, they depict the people, institutions, processes, issues, and policies involved in politics and government. Second, the way in which participants in government and politics interact with the media influences the way in which the media depict them. Third, the media’s depictions can have effects (positive AND negative) on our daily lives.

Media Empires

A few multinational conglomerates dominate the mass media; indeed, they are global media empires. Between them, they own the main television networks and production companies, most of the popular cable channels, the major movie studios, magazines, book publishers, and the top recording companies, and they have significant ownership interests in Internet media.

Other large corporations own the vast majority of newspapers, major magazines, television and radio stations, and cable systems. Many people live in places that have one newspaper, one cable-system owner, few radio formats, and one bookstore selling mainly best sellers. Furthering consolidation, in January 2011 the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved the merger of Comcast, the nation’s largest cable and home Internet provider, with NBC Universal, one of the major producers of television shows and movies and the owner of several local stations as well as such lucrative cable channels as MSNBC, CNBC, USA, Bravo, and SyFy.

Some scholars criticize the media industry for pursuing profits and focusing on the bottom line. They accuse it of failing to cover government and public affairs in-depth and of not presenting a wide range of views on policy issues.

The reliance of most of the mass media on advertising as their main source of revenue and profit can discourage them from giving prominence to challenging social and political issues and critical views. Advertisers usually want cheery contexts for their messages. While many criticize media conglomerates as having biased agendas, the reality is that media companies are biased only towards the maximization of profits to their investors and it is the viewers who establish the agenda that media companies follow in their viewing patterns.

For this reason, many experts have noted that we are moving from an era of mass broadcasting to very specialized “narrowcasting” meaning that viewers select the source of news and entertainment they wish to see based on their personal and cultural backgrounds and interests. The era of depending upon broadcasters to deliver the news is quickly coming to an end and is being replaced with a new era of consumer generated news and information resources. Nonetheless, the mass media contain abundant information about politics, government, and public policies and are still a vital part of our daily lives.

Types of Media

Newspapers

The core of the mass media of the departed twentieth-century was the newspaper. Even now, newspapers originate the overwhelming majority of domestic and foreign news.

During recent years, sales have plummeted as many people have given up or, as with the young, never acquired the newspaper habit. Further cutting into sales are newspapers’ free online versions. Revenue from advertising (automotive, employment, and real estate) has also drastically declined, with classified ads moving to Craigslist and specialist job-search sites. As a result, newspapers have slashed staff, closed foreign and domestic bureaus (including in Washington, DC), reduced reporting, and shrunk in size.

Nonetheless, there are still around 1,400 daily newspapers in the United States with estimated combined daily circulations of roughly forty million; many more millions read the news online. Chains of newspapers owned by corporations account for over 80 percent of circulation.

A few newspapers, notably the Wall Street Journal (2.1 million), USA Today (1.8 million), and the New York Times (877,000), are available nationwide.

The Wall Street Journal, although it has erected a paywall around its Internet content, claims an electronic readership of 450,000. Its success suggests that in the future some newspapers may go completely online—thus reducing much of their production and distribution costs.

Most newspapers, including thousands of weeklies, are aimed at local communities. But after losing advertising revenue, their coverage is less comprehensive. They are being challenged by digital versions of local newspapers, such as AOL’s Patch.com. [5] It has seven hundred sites, each in an affluent community, in nineteen states and the District of Columbia. AOL has hired journalists and equipped each of them with a laptop computer, digital camera, cell phone, and police scanner to publish up to five items of community news daily. Some of their stories have achieved prominence, as, for example, a 2009 report about the hazing of high school freshmen in Millburn, New Jersey. But the most popular posts are about the police, schools, and local sports; and “often the sites are like digital Yellow Pages.” [6]

Magazines

There are roughly five thousand magazines published on every conceivable subject. Five publishers account for around one-third of the total revenue generated. Political and social issues are commonly covered in newsweeklies such as Time and also appear in popular magazines such as People and Vanity Fair.

To survive, journals of political opinion usually depend on subsidies from wealthy individuals who support their views. The Weekly Standard, the voice of Republican neoconservatives and one of the most influential publications in Washington, with a circulation of approximately 75,000, loses around $5 million annually. It was initially owned and funded by media mogul Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, which makes big profits elsewhere through its diverse holdings, such as Fox News and the Wall Street Journal. In 2009, it sold the Weekly Standard to the conservative Clarity Media Group.

Television

People watch an average of thirty-four hours of television weekly. Over one thousand commercial, for-profit television stations in the United States broadcast over the airwaves; they also are carried, as required by federal law, by local cable providers. Most of them are affiliated with or, in fewer cases, owned by one of the networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox), which provide the bulk of their programming. These networks produce news, public affairs, and sports programs.

The commission and finance from production companies, many of which they own, the bulk of the entertainment programming shown on their stations and affiliates. The most desired viewers are between eighteen and forty-nine because advertisements are directed at them. So the shows often follow standard formats with recurring characters: situation comedies, dramas about police officers and investigators, and doctors and lawyers, as well as romance, dance, singing, and other competitions. Sometimes they are spin-offs from programs that have done well in the audience ratings or copies of successful shows from the United Kingdom. “Reality” programming, heavily edited and sometimes scripted, of real people put into staged situations or caught unaware, has become common because it draws an audience and usually costs less to make than written shows. The highest-rated telecasts are usually football games, exceeded only by the Academy Awards.

Unusual and risky programs are put on the air by networks and channels that may be doing poorly in the ratings and are willing to try something out of the ordinary to attract viewers. Executives at the relatively new Fox network commissioned The Simpsons. Matt Groening, its creator, has identified the show’s political message this way: “Figures of authority might not always have your best interests at heart.…Entertain and subvert, that’s my motto.” The show, satirizing American family life, government, politics, and the media, has become one of television’s longest running and most popular series worldwide.

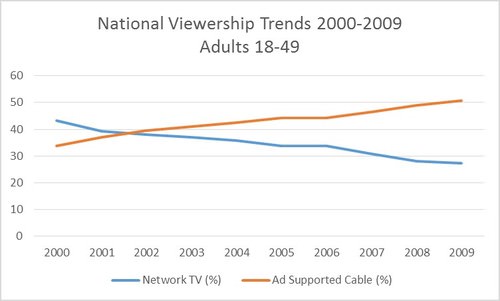

Cable is mainly a niche medium. Of the ninety or so ad-supported cable channels, ten (including USA, TNT, Fox News, A&E, and ESPN) have almost a third of all the viewers. Other channels occasionally attract audiences through programs that are notable (Mad Men on American Movie Classics) or notorious (Jersey Shore on MTV). Cable channels thrive (or at least survive) financially because they receive subscriber fees from cable companies such as Comcast and Time-Warner.

The networks still have the biggest audiences—the smallest of them (NBC) had more than twice as many viewers as the largest basic cable channel, USA. The networks’ evening news programs have an audience of 23 million per night compared with the 2.6 million of cable news.

Politics and government appear not only on television in news and public-affairs programs but also in courtroom dramas and cop shows. In the long-running and top-rated television show (with an audience of 21.93 million viewers on January 11, 2011), NCIS (Naval Criminal Investigative Service), a team of attractive special agents conduct criminal investigations. The show features technology, sex, villains, and suspense. The investigators and their institutions are usually portrayed positively.

Public Broadcasting

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) was created by the federal government in 1967 as a private, nonprofit corporation to oversee the development of public television and radio. [8] CPB receives an annual allocation from Congress. Most of the funds are funneled to the more than three hundred public television stations of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and to over six hundred public radio stations, most affiliated with National Public Radio (NPR), to cover operating costs and the production and purchase of programs.

CPB’s board members are appointed by the president, making public television and radio vulnerable or at least sensitive to the expectations of the incumbent administration. Congress sometimes charges the CPB to review programs for objectivity, balance, or fairness and to fund additional programs to correct alleged imbalances in views expressed. [9] Conservatives charge public broadcasting with a liberal bias. In 2011 the Republican majority in the House of Representatives sought to withdraw its federal government funding.

About half of public broadcasting stations’ budgets come from viewers and listeners, usually responding to unremitting on-air appeals. Other funding comes from state and local governments, from state colleges and universities housing many of the stations, and from foundations.

Corporations and local businesses underwrite programs in return for on-air acknowledgments akin to advertisements for their image and products. Their decisions on whether or not to underwrite a show tend to favor politically innocuous over provocative programs. Public television and radio thus face similar pressure from advertisers as their for-profit counterparts.

Public broadcasting delves into politics, particularly with its evening news programs and documentaries in its Frontline series. National Public Radio, with an audience of around 27 million listeners weekly, broadcasts lengthy news programs during the morning and evening with reports from domestic and foreign bureaus. NPR has several call-in current-events programs, such as The Diane Rehm Show. Guests from a spectrum of cultural life are interviewed by Terry Gross on her program Fresh Air. On the Media analyzes the news business in all its aspects, and Ira Glass’s This American Life features distinctive individuals delving into important issues and quirky subjects. Most of these programs are available via podcast from iTunes. Public Radio Exchange, PRX.org, has an abundance of programs from independent producers and local NPR stations.

Commercial Radio

Around ten thousand commercial FM and AM radio stations in the United States broadcast over the airwaves. During the 1990s, Congress and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) dropped many restrictions on ownership and essentially abandoned the requirement that stations must serve the “public interest.” This led to the demise of much public affairs programming and to a frenzy of mergers and acquisitions. Clear Channel Communications, then the nation’s largest owner, bought the second largest company, increasing its ownership to roughly 1,150 stations. The company was sold in 2008 to two private equity firms.

Most radio programming is aimed at an audience based on musical preference, racial or ethnic background and language, and interests (e.g., sports). Much of the news programming is supplied by a single company, Westwood One, a subsidiary of media conglomerate Viacom. Even on all-news stations, the reports are usually limited to headlines and brief details. Talk radio, dominated by conservative hosts, reaches large audiences.

Music

Four major companies produce, package, publicize, advertise, promote, and merchandise roughly 5,000 singles and 2,500 compact discs (CDs) each year. A key to success is getting a music video on MTV or similar stations. Around twelve million CDs used to be sold nationwide every week. This number has significantly decreased. The companies and performers now make music that is cheaply available online through services such as Apple’s iTunes store. Many people, especially students, download music from the Internet or burn CDs for themselves and others.

Music often contains political content. Contrast Green Day’s scathing 2005 hit song “American Idiot” and its lyric “One nation controlled by the media” with Lee Greenwood’s patriotic “God Bless the USA.” Some rap lyrics celebrate capitalism and consumerism, promote violence against women, and endorse—or even advocate—attacks on the police and other authority figures.

Films

The movie business is dominated by six major studios, which finance and distribute around 130 feature films each year. Mass-market logic usually pushes them to seek stories that “are sufficiently original that the audience will not feel it has already seen the movie, yet similar enough to past hits not to be too far out.” [10] Superheroes, science fiction and fantasy, sophomoric comedies, and animation dominate. Sequels are frequent. Special effects are common. In Robert Altman’s satire The Player, the protagonist says that the “certain elements” he needs to market a film successfully are violence, suspense, laughter, hope, heart, nudity, sex, and a happy ending.

It can cost well over $100 million to produce, advertise, and distribute a film to theaters. These costs are more or less recouped by the U.S. and overseas box office sales, DVD sales (declining) and rentals, revenue from selling broadcast rights to television, subscription cable, video on demand, and funds received from promoting products in the films (product placement). Increasingly important are Netflix and its competitors, which for a monthly charge make movies available by mail or streaming.

Many independent films are made, but few of them are distributed to theaters and even fewer seen by audiences. This situation is being changed by companies, such as Snag Films, that specialize in digital distribution and video on demand (including over the iPad). [11]

It is said in Hollywood that “politics is box office poison.” The financial failure of films concerned with U.S. involvement in Iraq, such as In the Valley of Elah, appears to confirm this axiom. Nonetheless, the major studios and independents do sometimes make politically relevant movies.

Books

Some 100,000 books are published annually. About “seventy percent of them will not earn back the money that their authors have been advanced.” [12] There are literally hundreds of publishers, but six produce 60 percent of all books sold in the United States. Publishers’ income comes mainly from sales. A few famous authors command multimillion-dollar advances: President Bill Clinton received more than $10 million and President Bush around $7 million to write their memoirs.

E-books are beginning to boom. The advantage for readers is obtaining the book cheaper and quicker than by mail or from a bookstore. For publishers, there are no more costs for printing, shipping, warehousing, and returns. But digital books could destroy bookstores if, for example, publishers sold them directly to the iPad. Indeed, publishers themselves could be eliminated if authors sold their rights to (say) Amazon.

Books featuring political revelations often receive widespread coverage in the rest of the media. They are excerpted in magazines and newspapers. Their authors appear on television and radio programs. An example is President George W. Bush’s former press secretary Scott McClellan, who, while praising the president in his memoir as authentic and sincere, also accused him of lacking in candor and competence. [13]

Electronic (“New”) Media

Recent technological innovations have shifted the entire media field from one of mass communication to a new arena that can best be described as “new media.” For our purposes, we will define new media as any type of media communication that relies on electronic technology (particularly the Internet). In just the past decade, rapid and, most likely, enduring shifts have taken place in the way in which we communicate with each other. The rising popularity of “smartphones” has meant that most of us have easy access to seemingly unlimited sources of news, information, and interpersonal communications (such as social media like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram).

Rather than relying on traditional mass media sources to deliver content to us, we ourselves have become both the creators AND consumers of digital content at astounding speed. Where just a decade ago, the “24-hour news cycle” seemed impressive, we are now in an era where personal electronics and digital cameras on most phones have allowed us to stream, tweet, blog, etc. in real time. Our daily lives are seemingly lived online and in real time. The implications of these new forms of technology are just beginning to be realized and utilized in the political process but it is fair to predict that the use and impact of new media will overshadow that of traditional media sources in the government process for many decades to come.

Mass Media and Politics

Political advertising is a form of campaigning used by political candidates to reach and influence voters. It can include several different mediums and span several months over the course of a political campaign. Unlike the campaigns of the past, advances in media technology have streamlined the process, giving candidates more options to reach even larger groups of constituents with very little physical effort.

Political advertising has changed drastically over the last several decades. During the 1952 Presidential elections, Dwight D. Eisenhower was the first candidate to extensively utilize television commercials, creating forty twenty-second spots to answer questions from everyday Americans. During the 1960 elections, both candidates--Vice President Richard Nixon and Senator John F. Kennedy--utilized television, although Kennedy's televised speech about his Catholic heritage and American religious tolerance is considered by many to be more memorable.

One of the first negative political advertisements was titled "The Daisy Girl" and was released by Lyndon Johnson's campaign during the 1964 election. The commercial showed a young girl picking the petals off a daisy, while a voice off camera began a countdown to a nuclear explosion. The ad ended with an appeal to vote for Johnson, "because the stakes are too high for you to stay home." Though the ad ran for under a minute and only aired once, it helped Johnson win the electoral votes of 44 states. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, political attack ads became even more prevalent, with Presidents Nixon, Carter, Reagan and George H. W. Bush all utilizing the method against their opponents.

The growth of cable television networks heavily influenced political advertising in the 1992 election between incumbent President George H. W. Bush and Governor Bill Clinton, particularly in reaching new target demographics such as women and young voters. The 2004 election saw yet another, and possibly the biggest, change yet in political advertising--the growth of the Internet. Web-based advertising was easily distributed by both incumbent President George W. Bush and Senator John Kerry's campaigns, and both campaigns hired firms who specialized in the accumulation of personal data. This resulted in advertisements which were tailored to target specific audiences for the first time (a process known as narrowcasting). The 2008 election was notable for Senator Barack Obama's use of the Internet to communicate directly and personally with supporters and constituents, a tactic that would help in his eventual victory.

Video: Political Ads in 2014 – “Good, Bad and Ugly

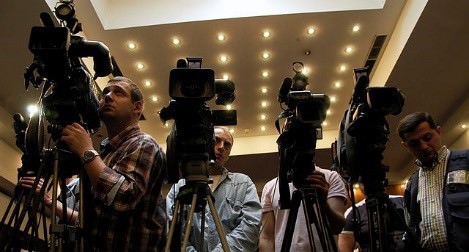

Politicians have learned that the media is the fastest and most efficient means of promoting themselves, drawing attention to a social or political issue, and proposing a government program or policy. But this must be balanced with the media’s traditional role as the “fourth estate” in overseeing, monitoring and exposing the actions of politicians.

One way that politicians attempt to guide the media’s focus is to give the members of the media carefully scripted events that they wish covered. Media events are carefully staged and highly publicized events where members of the media and the press are invited and encouraged to attend in order for politicians to gain exposure in an environment that is controlled by well prepared and high “handlers.” In most media events, little if any attention would be paid to the politician or candidate if the media were not there and the media benefits by having extended access to the candidate or politician.

A very good example of such a media event would be Barack Obama’s decision to invite TV and media crews to follow him as he went door to door thanking candidates for their support and asking them for continued support in his presidential campaign. While it was a media event, it made little difference on a personal level to the outcome of the Obama campaign as he reached out to only around 13 such households before ending the event when the cameras were turned off.

As seen earlier, the production of highly crafted TV commercials is an important tool, especially for candidates seeking office. Approximately 60 percent of presidential campaign spending is now devoted to Television ads but recent analysis says that about two-thirds of ads tend to carry a negative tone. The reason such negative ads tend to dominate the airwaves in tightly contested races is that they can carry a larger impact in 30 seconds than a much longer advertisement with a more positive image can, but the tradeoff is that the American public may actually consider a candidate’s use of negative ads as a detriment and may not respond in the way the candidate intended.

For this reason, some political scholars believe the use of negative campaign ads will eventually prove less effective and we should anticipate fewer of them in the future. But this may also be a result of social media campaigns which can carry negative messages to an even larger degree and may not be directly attributed to the candidate.

Ronald Reagan has been referred to as “the great communicator” because of his effective use of media strategies. This is as a result of President Reagan’s media and Hollywood background in radio and films. He truly understood the effectiveness of a well-crafted media persona.

Journalist Mark Hertsgaard has described the Reagan White House strategy as involving seven principles of media management. These include: (1) plan ahead; (2) stay on the offensive; (3) control the flow of information; (4) limit reporters’ access to the president; (5) talk about the issues you want to talk about; (6) speak in one unified voice; and (7) repeat the same message many times. [source: Mark Hertsgaard, On Bended Knee: The Press and the Reagan Presidency (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988), [34]. This proactive approach to media management has now become the standard not only for the president but also for the majority of government officials and candidates across the nation.

Media management did not, of course, begin with Ronald Reagan’s administration. As recently as Herbert Hoover’s presidency, reporters were required to submit their questions to the president in writing and he always responded to them in writing. Under the Roosevelt administration, media politics became an even greater part of the overall political process. It is under Roosevelt’s administration that such staples of the political process as press conferences and media events took place. One of the most important strategies of the Roosevelt administration was the use of radio with the now famous “fireside chats.”

Another example of media management during this period of time was Roosevelt’s ability to control the stories the media decided to report on. For instance, most of the public was totally unaware that President Roosevelt was in a wheelchair throughout his entire presidency (because he suffered from adult-onset polio). It was an unwritten yet heavily enforced rule that no mention was to be made nor pictures taken by the press of the president in his wheelchair or on crutches/braces.

By the 1960s, the “cozy relationship” between the press and the president had almost entirely evaporated. By the 1960s, reporters began to change their perceived role as passively covering the president’s activities to a more adversarial one in which a new type of reporting began to develop, known as investigative reporting. While media coverage had once only been favorable to the president this began to change as events such as the Vietnam War and Watergate began to unravel. Today, many journalists see their role as an investigative one yet most media owners and operators view the role of media today as providing entertainment. However, there is little doubt that media reporting had a great impact on many events in the 1960s and 1970s.

Questions to Ponder:

What is the role of the media today? Should it be an investigative one or should it be focused solely on entertaining and attracting audiences? Explain and defend your answer.

While, as we have seen in previous chapters, the First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees Freedom of the Press, the government does regulate some media. For the most part, print media are mostly unregulated, with newspapers and magazines given the freedom to print nearly anything as long as they don’t slander anyone. To date, the Internet has remained largely unregulated, despite ongoing congressional attempts to place restrictions on some controversial content.

Traditional broadcast media, however, are subject to the most government regulation. Radio and television broadcasters must obtain a license from the government because, according to American law, the public owns the airwaves. The agency in charge of issuing these licenses and overseeing and regulating the airwaves is The Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

Police Powers of the FCC

As a government regulatory agency, the FCC also has the responsibility to police the airwaves, and it can fine broadcasters for violating public decency standards on the air. In some cases, the FCC even has the power revoke a broadcaster’s license, keeping it off the air permanently. As an example, the FCC has fined radio host Howard Stern numerous times for his use of profanity, and fined CBS heavily for Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” during the halftime performance at the Super Bowl in 2004.

The FCC has not enforced the fairness doctrine since 1985, and some allege that the FCC has taken a lax approach to enforce the other rules as well. In May 2014, the last of these rules to be enforced (the equal time rule) was suspended leaving these provisions unenforced by the FCC.

Media Policing and Political Campaigns

The FCC has also established rules for broadcasts concerning political campaigns (also referred to as campaign media doctrines):

The right of rebuttal doctrine requires broadcasters to provide an opportunity for candidates to respond to criticisms made against them. In short, a station cannot air an attack on a candidate and fail to give the target of the attack a chance to respond.

The fairness doctrine, which states that a broadcaster who airs a controversial program must provide time to air opposing views.

Study/Discussion Questions

- What is the prime motivating factor/bias of mass media companies today? Why?

- How have traditional media sources been impacted by "new media"?

- Is social media a positive or negative trend in connecting the people with their government? Explain and defend your answer.

- What role does Hollywood play in connecting the people to the government? Give an example.

- How does music impact our political lives? What complaint did Green Day have about the music industry with this regard?

- What type of media access has traditionally been the most important to candidates running for elected office? Why?

- How did Ronald Reagan secure his reputation as "The Great Communicator?" What can other politicians learn from this?

- What role does the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) play with respect to the media?

Sources:

[2] A. J. Liebling, The Press (New York: Ballantine, 1964), 7.

[3] C. Edwin Baker argues for the importance of media diversity in Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

[4] Ben H. Bagdikian, The New Media Monopoly (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004).

5] Verne G. Kopytoff, “AOL Bets on Hyperlocal News, Finding Progress Where Many Have ny Have Failed,” New York Times, January 17, 2011, B3.

[7] Quoted in Sanjiv Bhattacharya, “Homer’s Odyssey,” Observer Magazine, August 6, 2000, 19.

[8] William Hoynes, Public Television for Sale (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994); and Marilyn Lashley, Public Television (New York: Greenwood, 1992).

[9] Twentieth-Century Fund Task Force on Public Television, Quality Time (New York: Twent ieth-Century Fund Press, 1993), 36.

[10] Mark Litwak, Reel Power (New York: Morrow, 1986), 74.

[11] Michael Cieply, “A Digital Niche for Indie Film,” New York Times, January 17, 2011, B5.

[12] Ken Auletta, “Publish or Perish,” The New Yorker, April 26, 2010, 24–31, is the source for much of this discussion; the quotation is on p. 30.

[13] Scott McClellan, What Happened: Inside the Bush White House and Washington’s Culture of Deception (New York: Public Affairs, 2008).

This text was adapted using Creative Commons license from the Saylor Foundation, http://www .saylor.org/site/textbooks/American%20Government%20and%20Politics%20in%20the%20Information %20Age.pd

Boundless. “News Coverage.” Boundless Political Science. Boundless, 03 Jul. 2014. Retrieved 30 Mar. 2015 from https://www.boundless.com/political-science/textbooks/boundless-political -science-textbook/media-10/media-and-campaigns-73/news-coverage-404-6168/

Boundless. “Political Advertisements.” Boundless Political Science. Boundless, 21 Jan. 2015. Retrieved 30 Mar. 2015 from https://www.boundless.com/political-science/textbooks/boundles s-political-science-textbook/media-10/media-and-campaigns-73/political-advertisements-402- 4346/

Edwards, G., & Wattenberg, M. (2011). The Development of Media Politics. In Government in America: People, politics, and policy (Brief 11th ed., Study ed., pp. 216-224). Boston: Longman.

Government Regulations of the Media. Retrieved March 30, 2015, from http://www.sparknotes. com/us-government-and-politics/american-government/the-media/section3.rhtml