6.11: Political Parties and Interest Groups Point of View

- Page ID

- 5878

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Lisa Simpson Goes to Washington

The media often depict interest group lobbyists negatively in the news and in entertainment. One particular episode of The Simpsons provides an extreme example. Lisa Simpson writes an essay titled “The Roots of Democracy” that wins her a trip to Washington, D.C., to compete for the best essay on patriotism award. She writes, “When America was born on that hot July day in 1776, the trees in Springfield Forest were tiny saplings…and as they were nourished by Mother Earth, so too did our fledgling nation find strength in the simple ideals of equality and justice.”

In Senator Bob Arnold’s office a lobbyist proposes to raze the Springfield National Forest. Arnold responds, “Well, Jerry, you’re a whale of a lobbyist, and I’d like to give you a logging permit, I would. But this isn’t like burying toxic waste. People are going to notice those trees are gone.” The lobbyist offers a bribe, which Arnold accepts.

Lisa sees it happen and tears up her essay. She sits on the steps of the Capitol and envisions politicians as cats scratching each other’s backs and lobbyists as pigs feeding from a trough. Called to the microphone at the “Patriots of Tomorrow” awards banquet, Lisa reads her revised essay, now titled “Cesspool on the Potomac.” A whirlwind of reform-minded zeal follows. Congressman Arnold is caught accepting a bribe to allow oil drilling on Mount Rushmore and is arrested and removed from office. Lisa does not win the essay contest.

Congressman Arnold is corrupt, but the cartoon’s unpunished instrument of corruption is the lobbyist.

Questions to Consider:

To what extent do interest groups pose a real threat to democracy today? How do interest groups contribute to our democratic system of government?

Video: A Critical View of Interest Groups

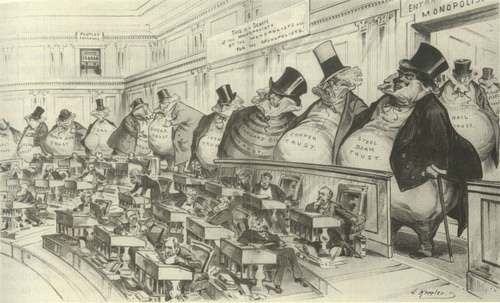

Interest groups are intermediaries linking people to government, and lobbyists work for them. These groups make demands on the government and try to influence public policies in their favor. Their most important difference from political parties is that they do not seek elective office but target their activities towards government officials and seek to have their ideological political agenda made into law or policy. Interest groups can be single entities, join associations, and have individual members.

The University of Texas at Austin is an educational institution. Its main purposes are teaching and research. Like other educational institutions, it is an interest group when it tries to influence government policies. These policies include government funding for facilities and student grants, loans, and work study. It may also try to influence laws and court decisions applying to research, admissions, gender equality in intercollegiate sports, and student records. It may ask members of Congress to earmark funds for some of its projects, thereby bypassing the normal competition with other universities for funds based on merit. [1B]

Single entities often join forces in associations. Associations represent their interests and make demands on the government on their behalf. The University of Texas belongs to the Association of American Universities. General Electric (GE) belongs to over eighty trade associations, each representing a different industry such as mining, aerospace, and home appliances. [2]

Many interest groups have individuals as members. People join labor unions and professional organizations (e.g., associations for lawyers or political scientists) that claim to represent their interests.

Types of Interest Groups

Interest groups can be divided into five types: economic, societal, ideological, public interest, and governmental.

Economic Interest Groups

The major economic interest groups represent businesses, labor unions, and professions. Business interest groups consist of industries, corporations, and trade associations. Unions usually represent individual trades, such as the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Most unions belong to an association, the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO).

Economic interest groups represent every aspect of our economy, including agriculture, the arts, automobiles, banking, beverages, construction, defense, education, energy, finance, food, health, housing, insurance, law, media, medicine, pharmaceuticals, sports, telecommunications, transportation, travel, and utilities. These groups cover from head (i.e., the Headwear Institute of America) to toe (i.e., the American Podiatric Medical Association) and from soup (i.e., the Campbell Soup Company) to nuts (i.e., the Peanut Butter and Nut Processors Association). [3]

Source: blog.cozic.fr/wp-content/uploads/2007/11/logo_service_non_20.jpg Creative Commons Fair Use (Bing Image Search)

Societal Interest Groups

Societal interest groups focus on interests based on people’s characteristics, such as age, gender, race, and ethnicity, as well as religion and sexual preference. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is one of the oldest societal interest groups in the United States. Other similar groups are the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF), and the National Council of American Indians.

Ideological Interest Groups

Ideological interest groups promote a reactionary, conservative, liberal, or radical political philosophy through research and advocacy. Interest groups that take stands on such controversial issues as abortion and gun control are considered ideological, although some might argue that they are actually public interest groups.

Public Interest Groups

Public interest groups work for widely accepted concepts of the common good, such as the family, human rights, and consumers. Although their goals are usually popular, some of their specific positions (e.g., environmental groups opposing offshore drilling for oil) may be controversial and challenged.

Governmental Interest Groups

Government interest groups consist of local, state, and foreign governments. They seek to influence the relevant policies and expenditures of the federal government.

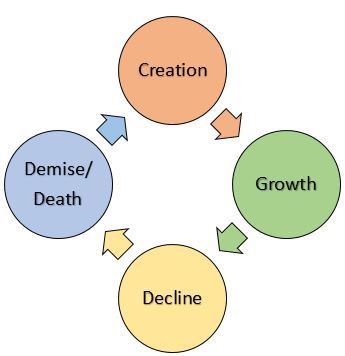

Life Stages of Interest Groups

As the United States has become more complex with new technologies, products, services, businesses, and professions, the US government has become more involved in the economy and society. People with common interests organize to solicit support and solutions to their problems from the government. Policies enacted in response to the efforts of these groups affect other people, who then form groups to seek government intervention for themselves. These groups may give rise to additional groups. [4]

Some interest groups are created in reaction to an event or a perceived grievance. The National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) was founded in 1973 in response to the US Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision earlier that year legalizing abortion. However, groups may form long after the reasons for establishing them are obvious. The NAACP was not founded until 1909 even though segregation of and discrimination against black people had existed for many years.

Link: Oral Arguments in Roe v. Wade

Listen to oral arguments in the Roe v. Wade at Oyez: Roe v. Wade.

Interest Group Entrepreneurs

Interest group entrepreneurs are individuals who organize, promote, and often lead an interest group in its activities. Often they are responding to events in their lives. After a drunk driver killed one of her daughters, Candy Lightner founded Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) in 1980. She thereby identified latent interests: people who could be grouped together and organized to pursue what she made them realize was a shared goal, punishing and getting drunk drivers off the road. She was helped by widespread media coverage that brought public attention to her loss and cause.

Evolution

Interest groups can change over time. The National Rifle Association (NRA) started out as a sports organization in the late nineteenth century dedicated to improving its members’ marksmanship. It became an advocate for law and order in the 1960s until its official support for the 1968 Gun Control Act brought dissension in its ranks. Since the election of new leaders in 1977, the NRA has focused on the Second Amendment right to bear arms, opposing legislation restricting the sale or distribution of guns and ammunition. [5]

Demise

Interest groups can also die. They may run out of funds. Their issues may lose popularity or become irrelevant. Slavery no longer exists in the United States and thus neither does the American Anti-Slavery Society.

How Interest Groups are Organized

Leaders and Staff

Interest groups have leaders and staff. They control the group, decide its policy objectives, and recruit and represent members. Leaders and top staff usually run the interest group. They do so because they command its resources and information flow and have the experience and expertise to deal with public policies that are often complex and technical. Almost a century ago, Robert Michels identified this control by an organization’s leaders and staff and called it “the iron law of oligarchy.” [6]

This oligarchy, or rule by the few, applies to single-entity interest groups and to most associations. Their leaders are appointed or elected and select the staff. Even in many membership organizations, the people who belong do not elect the leaders and have little input when the leaders decide policy objectives. [7] Their participation is limited to sending in dues, expressing opinions and, if membership is voluntary, leaving when dissatisfied.

Voluntary Membership

People join membership interest groups voluntarily or because they have no choice. When a membership is voluntary, interest groups must recruit and try to retain members. Members help fund the group’s activities, legitimize its objectives, and add credibility with the media.

Some people may not realize or accept that they have shared interests with others on a particular issue. For example, many young adults download music from the Internet, but few of them have joined the Future of Music Coalition, which is developing ways to do this legally. Others may be unwilling to court conflict by joining a group representing oppressed minorities or espousing controversial or unpopular views even when they agree with the group’s views.[8]

People do not need to join an interest group voluntarily when they can benefit from its activities without becoming a member. This is the problem of collective goods. Laws successfully lobbied for by environmental organizations that lead to cleaner air and water benefit members and nonmembers alike. However, the latter get a free ride. [9]

Membership Incentives

There are three types of incentives that, alone or in combination, may overcome this free-rider problem. A purposive incentive leads people voluntarily to join and contribute money to a group because they want to help the group achieve its goals. Membership in the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) increased by one hundred thousand in the eighteen months following the 9/11 attacks as the group raised concerns that the government’s antiterrorism campaign was harming civil liberties. [10] In addition, people may join groups, such as the Union of Concerned Scientists, because of a solidary incentive. The motivation to join the group stems from the pleasure of interacting with like-minded individuals and the gratification of publicly expressing one’s beliefs.

People may also join groups to obtain material incentives available only to members. AARP, formerly the American Association of Retired Persons, has around thirty-five million members. It obtains this huge number by charging a nominal annual membership fee and offering such material incentives as health insurance and reduced prices for prescription drugs. The group’s magazine is sent to members and includes tax advice, travel and vacation information, and discounts.

Recruitment

One way interest groups recruit members is through media coverage. The appealingly named Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) is a consumer organization that focuses on food and nutrition issues, produces quality research, and has media savvy. It is a valuable source of expertise and information for journalists. The frequent and favorable news coverage it receives brings the group and its activities to the public’s attention and encourages people to support and join it.

Video: Media Coverage of Science in the Public Interest Lawsuit

News coverage of an interest group does not always have to be favorable to attract members. Oftentimes, stories about the NRA in major newspapers are negative. Presenting this negative coverage as bias and hostility against and attacks on gun owners, the group’s leaders transform it into purposive and solidary incentives. They use e-mail “to power membership mobilization, fund raising, single-issue voting and the other actions-in-solidarity that contribute to [their] success.” [11]

Video: ASPCA Recruiting

Groups also make personalized appeals to recruit members and solicit financial contributions. Names of people who might be sympathetic to a group are obtained by purchasing mailing lists from magazines, other groups, and political parties. Recruitment letters and e-mails often feature scare statements, such as a claim that Social Security is in jeopardy.

Interest groups recruit members, publicize their activities, and pursue their policy objectives through the new media. The Save Our Environment Action Center consists of twenty national environmental groups pooling their databases of supporters and establishing a website. Through this network, people can receive informational newsletters via e-mail, sign petitions, and contact their representatives.

Required Membership

Many labor unions in the united states place contractual obligations in their employment agreements that require new hires be enrolled as dues paying members of the union before they can begin work. Employment in most automobile plants requires that workers are members of the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW). Workers fought to establish unions to improve their wages, working conditions, and job opportunities. One way of achieving these objectives was to require all workers at a plant to be union members. But union membership has plummeted as the United States has moved from a manufacturing to a service economy and employers have effectively discouraged unionization. Many jobs do not have unions for workers to join whether they want to or not. Today only about 12 percent of workers belong to a union compared to a high of 35.5 percent in 1945. Only 7 percent of private sector workers belong to a union. A majority of union members now work for the government.

Video: Labor Unions: The Costs and Benefits

Study/Discussion Questions

- Why do you think some interest groups have a bad reputation? What social purpose do interest groups serve?

- Do you support any interest groups? What made you decide to support them?

- What are the different ways interest groups can influence policies? Do you think interest groups should be allowed to contribute as much as they want to political campaigns?

Research

Use the Internet and other sources to investigate and identify examples of as many types of interest groups as you can. Use PowerPoint or other presentation software to compare and contrast these interest groups and their activities.

For each interest group, consider:

- What are the basic ideologies or policies this group believes in?

- Which political party is this group most attractive to – Democrats (liberal) or Republicans (conservative)?

- How does the group recruit and retain its members?

- What selective or exclusive benefits does the group offer its members?

- What type of lobbying does this group do?

- How does this group raise its funding? Member dues, voluntary contributions? Political Action Committee donations?

- What type of contributions has this group made to candidates?

- How successful has this group been in influencing political policies or lawmakers?

Sources:

[1] James D. Savage, Funding Science in America: Congress, Universities, and the Politics of the Academic Pork Barrel (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999); and Jeffrey Brainard and J. J. Hermes, “Colleges’ Earmarks Grow, Amid Criticism,” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 28, 2008.

[2] Kay Lehman Schlozman and John T. Tierney, Organized Interests and American Democracy (New York: Harper & Row, 1986), 72–73.

[3] Jeffrey H. Birnbaum, The Lobbyists: How Influence Peddlers Work Their Way in Washington (New York: Times Books, 1993), 36.

[4] This is known as disturbance theory. It was developed by David B. Truman in The Governmental Process: Political Interests and Public Opinion, 2nd ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971), chap. 4; and it was amplified by Robert H. Salisbury in “An Exchange Theory of Interest Groups,” Midwest Journal of Political Science 13 (1969): 1–32.

[5] Scott H. Ainsworth, Analyzing Interest Groups: Group Influence on People and Policies (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002), 87–88.

[6] Robert Michels, Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy (New York: Dover Publications, 1959; first published 1915 by Free Press).

[7] Scott H. Ainsworth, Analyzing Interest Groups: Group Influence on People and Policies (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002), 114–15.

[8] Scott Sigmund Gartner and Gary M. Segura, “Appearances Can Be Deceiving: Self Selection, Social Group Identification, and Political Mobilization,” Rationality and Society9 (1977): 132–33.

[9] See Mancur Olson Jr., The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965).

[10] Eric Lichtblau, “F.B.I. Leader Wins a Few at Meeting of A.C.L.U.,” New York Times, June 14, 2003, accessed March 23, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2003/06/14/us/fbi-leader- wins-a-few-at-meeting-of-aclu.html?ref=ericlichtblau.

[11] Brian Anse Patrick, The National Rifle Association and the Media: The Motivating Force of Negative Coverage (New York: Peter Lang, 2002), 9.

[12] William J. Puette, Through Jaundiced Eyes: How the Media View Organized Labor(Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, 1992).

[13] For an exception, see Deepa Kumar, Outside The Box: Corporate Media, Globalization, and the UPS Strike (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007).

[14] Affirmative Advocacy: Race, Class, and Gender in Interest Group Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

[15] Michael M. Franz, Choices and Changes: Interest Groups in the Electoral Process (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2008), 7.

[16] The case is Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, No. 08–205. See also Adam Liptak, “Justices, 5-4, Reject Corporate Spending Limit,” New York Times, January 21, 2010, accessed March 23, 2011,http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/22/us/politics/22scotus.html.

[17] Don Van Natta Jr., “Enron’s Collapse: Campaign Finance; Enron or Andersen Made Donations to Almost All Their Congressional Investigators,” New York Times, January 25, 2002, accessed March 23, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/25/business/enron-s-collapse -campaign-finance-enron-andersen-made-donations-almost-all- their.html.

[18] Mark Green, “Political PAC-Man,” New Republic 187, no. 24 (December 13, 1982): 18.

[19] Center for Responsive Politics, “Money and Medicare: Campaign Contributions Correlate with Vote,” OpenSecrets Blog, November 24, 2003,http://www.opensecrets.org/capital_eye/in side.php?ID=113.