2.1: The Role of Government

- Page ID

- 6771

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Role of the Government

Government plays a role in the marketplace. Sometimes the government creates laws to protect labor, consumers, or industries. In other cases, the government is concerned with encouraging competition and regulating big business for the public welfare. When this happens, the government is modifying the marketplace. Economists would then define our economic system as a “modified free enterprise economy” because it consists of three different market structures, various types of business organizations, and a varying degree of government laws and regulations.

Universal Generalizations

- Public disclosure is used to promote competition.

- Today, the United States government takes part in economic affairs to promote and encourage competition.

- The modern American free enterprise market is a mixture of various markets, business organizations, and government regulations.

Guiding Questions

- Should the United States government still enforce anti-monopoly legislation?

- How does the federal government attempt to preserve competition among businesses?

- How can public disclosure be used to prevent market failures?

Regulating Anticompetitive Behavior

In the closing decades of the 1800s, many industries in the U.S. economy were dominated by a single firm that had most of the sales for the entire country. Supporters of these large firms argued that they could take advantage of economies of scale and careful planning to provide consumers with products at low prices. However, critics pointed out that when competition was reduced, these firms were free to charge more and make permanently higher profits, and that without the goading of competition, it was not clear that they were as efficient or innovative as they could be.

| Anti-Monopoly Legislation | Description |

| Sherman Anti-trust Act 1890 | First significant law against monopolies; sought to do away with monopolies and restraints that hinder competition |

| Clayton Anti-Trust Act 1914 | Law gives government greater power against monopolies; outlawed price discrimination |

| Federal Trade Commission (FTC) 1914 | Administers antitrust laws forbidding unfair competition, price fixing, and other deceptive practices; used in conjunction with the Clayton Act |

| Robin-Patman Act 1936 | Strengthened the Clayton Act, companies cannot offer special discounts to some consumers while denying them to others |

Antitrust Laws

In many cases, these large firms were organized in the legal form of a “trust” in which a group of formerly independent firms were consolidated together by mergers and purchases, and a group of “trustees” then ran the companies as if they were a single firm. Thus, when the U.S. government passed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890 to limit the power of these trusts, it was called an antitrust law. In an early demonstration of the law’s power, in 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the government’s right to break up Standard Oil, which had controlled about 90% of the country’s oil refining. Standard Oil was broken into 34 independent firms, including Exxon, Mobil, Amoco, and Chevron. In 1914, the Clayton Antitrust Act outlawed mergers and acquisitions (where the outcome would be to “substantially lessen competition” in an industry), price discrimination (where different customers are charged different prices for the same product), and tied sales (where purchase of one product commits the buyer to purchase some other product). Also in 1914, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was created to define more specifically what competition was unfair. In 1950, the Celler-Kefauver Act extended the Clayton Act by restricting vertical and conglomerate mergers. In the twenty-first century, the FTC and the U.S. Department of Justice continue to enforce antitrust laws.

| Federal Regulatory Agency | Description |

| Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 1906 | Enforces laws to ensure purity, effectiveness, and truthful labeling of food, drugs cosmetics; inspections production and shipment of these products |

| Federal Trade Commission (FTC) 1914 | Administers antitrust laws forbidding unfair competition, price fixing, and other deceptive practices |

| Federal Communications Commission (FCC) 1934 | Licenses and regulates radio and television stations and regulates interstate telephone, telegraph rates and services |

| Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) 1934 | Regulates and supervises the sale of securities and the brokers, dealers, and bankers who sell them |

| National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) 1935 | Administers federal labor-management relations laws; settles labor disputes; prevents unfair labor practices |

| Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) 1958 | Oversees the airline industry |

| Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) 1964 | Investigates and rules on charges of discrimination by employers and labor unions |

| Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 1970 | Protects the environment |

| Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) 1970 | Investigates accidents at the workplace; enforces regulations to protect employees at work |

| Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) 1972 | Develops standards of safety for consumer goods |

| Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) 1974 | Regulates civilian use of nuclear materials and facilities |

| Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) 1977 | Supervises transmission of the various forms of energy |

The U.S. antitrust laws reach beyond blocking mergers that would reduce competition to include a wide array of anticompetitive practices. For example, it is illegal for competitors to form a cartel to collude to make pricing and output decisions as if they were a monopoly firm. The Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice prohibit firms from agreeing to fix prices or output, rigging bids, or sharing or dividing markets by allocating customers, suppliers, territories, or lines of commerce.

In the late 1990s, for example, the antitrust regulators prosecuted an international cartel of vitamin manufacturers, including the Swiss firm Hoffman-La Roche, the German firm BASF, and the French firm Rhone-Poulenc. These firms reached agreements on how much to produce, how much to charge, and which firm would sell to which customers. The high-priced vitamins were then bought by firms like General Mills, Kellogg, Purina-Mills, and Proctor and Gamble, which pushed up the prices more. Hoffman-La Roche pleaded guilty in May 1999 and agreed both to pay a fine of $500 million and to have at least one top executive serve four months of jail time.

Under U.S. antitrust laws, a monopoly itself is not illegal. If a firm has a monopoly because of a newly patented invention, for example, the law explicitly allows a firm to earn higher-than-normal profits for a time as a reward for innovation. If a firm achieves a large share of the market by producing a better product at a lower price, such behavior is not prohibited by antitrust law.

Restrictive Practices

The antitrust law includes rules against restrictive practices—practices that do not involve outright agreements to raise price or to reduce the quantity produced, but that might have the effect of reducing competition. Antitrust cases involving restrictive practices are often controversial because they delve into specific contracts or agreements between firms that are allowed in some cases but not in others.

For example, if a product manufacturer is selling to a group of dealers who then sell to the general public it is illegal for the manufacturer to demand a minimum resale price maintenance agreement, which would require the dealers to sell for at least a certain minimum price. A minimum price contract is illegal because it would restrict competition among dealers. However, the manufacturer is legally allowed to “suggest” minimum prices and to stop selling to dealers who regularly undercut the suggested price. If you think this rule sounds like a fairly subtle distinction, you are right.

An exclusive dealing agreement between a manufacturer and a dealer can be legal or illegal. It is legal if the purpose of the contract is to encourage competition between dealers. For example, it is legal for the Ford Motor Company to sell its cars to only Ford dealers, for General Motors to sell to only GM dealers, and so on. However, exclusive deals may also limit competition. If one large retailer obtained the exclusive rights to be the sole distributor of televisions, computers, and audio equipment made by a number of companies, then this exclusive contract would have an anticompetitive effect on other retailers.

Tying sales happen when a customer is required to buy one product only if the customer also buys a second product. Tying sales are controversial because they force consumers to purchase a product that they may not actually want or need. Further, the additional, required products are not necessarily advantageous to the customer. Suppose that to purchase a popular DVD, the store required that you also purchase a portable TV of a certain model. These products are only loosely related, thus there is no reason to make the purchase of one contingent on the other. Even if a customer was interested in a portable TV, the tying to a particular model prevents the customer from having the option of selecting one from the numerous types available in the market. A related, but not identical, concept is called bundling, where two or more products are sold as one. Bundling typically offers an advantage for the consumer by allowing them to acquire multiple products or services for a better price. For example, several cable companies allow customers to buy products like cable, internet, and a phone line through a special price available through bundling. Customers are also welcome to purchase these products separately, but the price of bundling is usually more appealing.

In some cases, tying sales and bundling can be viewed as anticompetitive. However, in other cases, they may be legal and even common. It is common for people to purchase season tickets to a sports team or a set of concerts so that they can be guaranteed tickets to the few contests or shows that are most popular and likely to sell out. Computer software manufacturers may often bundle together a number of different programs, even when the buyer wants only a few of the programs. Think about the software that is included in a new computer purchase, for example.

Recall that predatory pricing occurs when the existing firm (or firms) reacts to a new firm by dropping prices very low until the new firm is driven out of the market, at which point the existing firm raises prices again. This pattern of pricing is aimed at deterring the entry of new firms into the market. But in practice, it can be hard to figure out when pricing should be considered predatory. Say that American Airlines is flying between two cities, and a new airline starts flying between the same two cities, at a lower price. If American Airlines cuts its price to match the new entrant, is this predatory pricing? Or is it just market competition at work? A commonly proposed rule is that if a firm is selling for less than its average variable cost—that is, at a price where it should be shutting down—then there is evidence for predatory pricing. But calculating in the real world what costs are variable and what costs are fixed is often not obvious, either.

The most famous restrictive practices case of recent years was a series of lawsuits by the U.S. government against Microsoft—lawsuits that were encouraged by some of Microsoft’s competitors. All sides admitted that Microsoft’s Windows program had a near-monopoly position in the market for the software used in general computer operating systems. All sides agreed that the software had many satisfied customers. All sides agreed that the capabilities of computer software that was compatible with Windows—both software produced by Microsoft and that produced by other companies—had expanded dramatically in the 1990s. Having a monopoly or a near-monopoly is not necessarily illegal in and of itself, but in cases where one company controls a great deal of the market, antitrust regulators look at any allegations of restrictive practices with special care.

The antitrust regulators argued that Microsoft had gone beyond profiting from its software innovations and its dominant position in the software market for operating systems, and had tried to use its market power in operating systems software to take over other parts of the software industry. For example, the government argued that Microsoft had engaged in an anticompetitive form of exclusive dealing by threatening computer makers that, if they did not leave another firm’s software off their machines (specifically, Netscape’s Internet browser), then Microsoft would not sell them its operating system software. Microsoft was accused by the government antitrust regulators of tying together its Windows operating system software, where it had a monopoly, with its Internet Explorer browser software, where it did not have a monopoly, and thus using this bundling as an anticompetitive tool. Microsoft was also accused of a form of predatory pricing; namely, giving away certain additional software products for free as part of Windows, as a way of driving out the competition from other makers of the software.

In April 2000, a federal court held that Microsoft’s behavior had crossed the line into unfair competition, and recommended that the company be broken into two competing firms. However, that penalty was overturned on appeal, and in November 2002 Microsoft reached a settlement with the government that it would end its restrictive practices.

The concept of restrictive practices is continually evolving, as firms seek new ways to earn profits and government regulators define what is permissible and what is not. A situation where the law is evolving and changing is always somewhat troublesome since laws are most useful and fair when firms know what they are in advance. In addition, since the law is open to interpretation, competitors who are losing out in the market can accuse successful firms of anticompetitive restrictive practices, and try to win through government regulation what they have failed to accomplish in the market. Officials at the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice are, of course, aware of these issues, but there is no easy way to resolve them.

Firms are blocked by antitrust authorities from openly colluding to form a cartel that will reduce output and raise prices. Companies sometimes attempt to find other ways around these restrictions and, consequently, many antitrust cases involve restrictive practices that can reduce competition in certain circumstances, like tie-in sales, bundling, and predatory pricing.

Visit this website to read an article about Google’s run-in with the FTC:

http://business.time.com/2013/01/04/googles-federal-antitrust-deal-cheered-by-some-jeered-by-others/

How Governments Can Encourage Innovation

A number of different government policies can increase the incentives to innovate, including: guaranteeing intellectual property rights, government assistance with the costs of research and development, and cooperative research ventures between universities and companies.

Intellectual Property Rights

One way to increase new technology is to guarantee the innovator an exclusive right to that new product or process. Intellectual property rights include patents, which give the inventor the exclusive legal right to make, use, or sell the invention for a limited time, and copyright laws, which give the author an exclusive legal right over works of literature, music, film/video, and pictures. For example, if a pharmaceutical firm has a patent on a new drug, then no other firm can manufacture or sell that drug for twenty-one years, unless the firm with the patent grants permission. Without a patent, the pharmaceutical firm would have to face competition for any successful products, and could earn no more than a normal rate of profit. With a patent, a firm is able to earn monopoly profits on its product for a period of time—which offers an incentive for research and development. In general, how long can “a period of time” be? The Clear it Up discusses patent and copyright protection timeframes for some works you might have heard of.

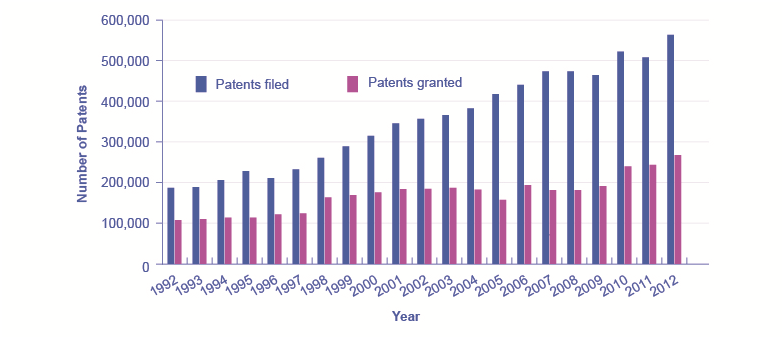

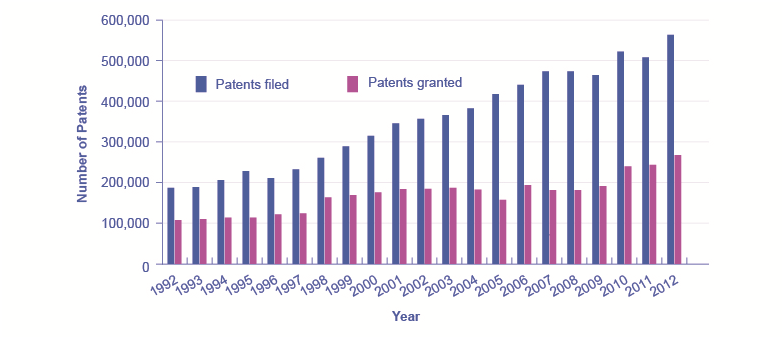

Figure 1 illustrates how the total number of patent applications filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, as well as the total number of patents granted, surged in the mid-1990s with the invention of the Internet, and is still going strong today.

Patents Filed and Granted, 1981–2008

The number of applications filed for patents increased substantially from the mid-1990s into the first years of the 2000s, due in part to the invention of the Internet, which has led to many other inventions and to the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act. (Source: http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/us_stat.htm)

While patents provide an incentive to innovate by protecting the innovator, they are not perfect. For example:

- In countries that already have patents, economic studies show that inventors receive only one-third to one-half of the total economic value of their inventions.

- In a fast-moving high-technology industry like biotechnology or semiconductor design, patents may be almost irrelevant because technology is advancing so quickly.

- Not every new idea can be protected with a patent or a copyright—for example, a new way of organizing a factory or a new way of training employees.

- Patents may sometimes cover too much or be granted too easily. In the early 1970s, Xerox had received over 1,700 patents on various elements of the photocopy machine. Every time Xerox improved the photocopier, it received a patent on the improvement.

- The 21-year time period for a patent is somewhat arbitrary. Ideally, a patent should cover a long enough period of time for the inventor to earn a good return, but not so long that it allows the inventor to charge a monopoly price permanently.

Public Goods

Even though new technology creates positive externalities, so perhaps one-third or one-half of the social benefit of new inventions spills over to others, the inventor still receives some private return. What about a situation where the positive externalities are so extensive that private firms could not expect to receive any of the social benefits? This kind of good is called a public good. Spending on national defense is a good example of a public good. Let’s begin by defining the characteristics of a public good and discussing why these characteristics make it difficult for private firms to supply public goods. Then we will see how the government may step in to address the issue.

The Definition of a Public Good

Economists have a strict definition of a public good, and it does not necessarily include all goods financed through taxes. To understand the defining characteristics of a public good, first consider an ordinary private good, like a piece of pizza. A piece of pizza can be bought and sold fairly easily because it is a separate and identifiable item. However, public goods are not separate and identifiable in this way.

Instead, public goods have two defining characteristics: they are nonexcludable and nonrivalrous. The first characteristic, a public good is nonexcludable, means that it is costly or impossible to exclude someone from using the good. If Larry buys a private good like a piece of pizza, then he can exclude others, like Lorna, from eating that pizza. However, if national defense is being provided, then it includes everyone. Even if you strongly disagree with America’s defense policies or with the level of defense spending, the national defense still protects you. You cannot choose to be unprotected, and national defense cannot protect everyone else and exclude you.

The second main characteristic of a public good, that it is nonrivalrous, means that when one person uses the public good, another can also use it. With a private good like pizza, if Max is eating the pizza then Michelle cannot also eat it; that is, the two people are rivals in consumption. With a public good like national defense, Max’s consumption of national defense does not reduce the amount left for Michelle, so they are nonrivalrous in this area.

A number of government services are examples of public goods. For instance, it would not be easy to provide fire and police service so some people in a neighborhood would be protected from the burning and burglary of their property, while others would not be protected at all. Protecting some necessarily means protecting others, too.

Positive externalities and public goods are closely related concepts. Public goods have positive externalities, like police protection or public health funding. Not all goods and services with positive externalities, however, are public goods. Investments in education have huge positive spillovers but can be provided by a private company. Private companies can invest in new inventions such as the Apple iPad and reap profits that may not capture all of the social benefits. Patents can also be described as an attempt to make new inventions into private goods, which are excludable and rivalrous, so no one but the inventor is allowed to use them during the length of the patent.

The Free Rider Problem of Public Goods

Private companies find it difficult to produce public goods. If a good or service is nonexcludable, like national defense, so that it is impossible or very costly to exclude people from using this good or service, then how can a firm charge people for it?

When individuals make decisions about buying a public good, a free rider problem can arise, in which people have an incentive to let others pay for the public good and then to “free ride” on the purchases of others. The free rider problem can be expressed in terms of the prisoner’s dilemma game, which is discussed as a representation of oligopoly in Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly. Say that two people are thinking about contributing to a public good: Rachel and Samuel. When either of them contributes to a public good, such as a local fire department, their personal cost of doing so is $4 and the social benefit of that person’s contribution is $6. Because society’s benefit of $6 is greater than the cost of $4, the investment is a good idea for society as a whole. The problem is that, while Rachel and Samuel pay for the entire cost of their contribution to the public good, they receive only half of the benefit, because the benefit of the public good is divided equally among the members of society. This sets up the prisoner’s dilemma illustrated in Table 2

| Samuel (S) Contribute | Samuel (S) Do Not Contribute | |

| Rachel (R) Contribute |

R pays $4, receives $6, net gain +$2 S pays $4, receives $6, net gain +$2 |

R pays $4, receives $3, net gain –$1 S pays $0, receives $3, net gain +$3 |

| Rachel (R) Do Not Contribute |

R pays $0, receives $3, net gain +$3 S pays $4, receives $3, net gain –$1 |

R pays $0, receives $0 S pays $0, receives $0 |

Contributing to a Public Good as a Prisoner’s Dilemma

If neither Rachel nor Samuel contributes to the public good, then there are no costs and no benefits of the public good. Suppose, however, that only Rachel contributes, while Samuel does not. Rachel incurs a cost of $4, but receives only $3 of benefit (half of the total $6 of benefit to society), while Samuel incurs no cost, and yet he also receives $3 of benefit. In this outcome, Rachel actually loses $1 while Samuel gains $3. A similar outcome, albeit with roles reversed, would occur if Samuel had contributed, but Rachel had not. Finally, if both parties contribute, then each incurs a cost of $4 and each receives $6 of benefit (half of the total $12 benefit to society). There is a dilemma with the Prisoner’s Dilemma, though.

Visit this website to read about a connection between free riders and “bad" music:

The Role of Government in Paying for Public Goods

The key insight in paying for public goods is to find a way of assuring that everyone will make a contribution and to prevent free riders. For example, if people come together through the political process and agree to pay taxes and make group decisions about the quantity of public goods, they can defeat the free rider problem by requiring, through the law, that everyone contributes.

However, government spending and taxes are not the only way to provide public goods. In some cases, markets can produce public goods. For example, think about radio. It is nonexcludable, since once the radio signal is being broadcast, it would be very difficult to stop someone from receiving it. It is nonrivalrous, since one person listening to the signal does not prevent others from listening as well. Because of these features, it is practically impossible to charge listeners directly for listening to conventional radio broadcasts.

Radio has found a way to collect revenue by selling advertising, which is an indirect way of “charging” listeners by taking up some of their time. Ultimately, consumers who purchase the goods advertised are also paying for the radio service, since the cost of advertising is built into the product cost. In a more recent development, satellite radio companies, such as SirusXM, charge a regular subscription fee for streaming music without commercials. In this case, however, the product is excludable—only those who pay for the subscription will receive the broadcast.

Some public goods will also have a mixture of public provision at no charge along with fees for some purposes. For example, a public city park may be free to use, but the government charges a fee for parking your car, for reserving certain picnic grounds, and for food sold at a refreshment stand.

In other cases, social pressures and personal appeals can be used, rather than the force of law, to reduce the number of free riders and to collect resources for the public good. For example, neighbors sometimes form an association to carry out beautification projects or to patrol their area after dark to discourage crime. In low-income countries, where social pressure strongly encourages all farmers to participate, farmers in a region may come together to work on a large irrigation project that will benefit all. Many fundraising efforts, including raising money for local charities and for the endowments of colleges and universities, also can be viewed as an attempt to use social pressure to discourage free riding and to generate the outcome that will produce a public benefit.

Common Resources and the “Tragedy of the Commons”

There are some goods that do not fall neatly into the categories of private good or public good. While it is easy to classify a pizza as a private good and a city park as a public good, what about an item that is nonexcludable and rivalrous, such as the queen conch?

In the Caribbean, the queen conch is a large marine mollusk found in shallow waters of seagrass. These waters are so shallow, and so clear, that a single diver may harvest many conch in a single day. Not only is conch meat a local delicacy and an important part of the local diet, but also, the large ornate shells are used in art and can be crafted into musical instruments. Because almost anyone with a small boat, snorkel, and mask, can participate in the conch harvest, it is essentially nonexcludable. At the same time, fishing for conch is rivalrous; once a diver catches one conch it cannot be caught by another diver.

Goods that are nonexcludable and rivalrous are called common resources. Because the waters of the Caribbean are open to all conch fishermen, and because any conch that you catch is conch that I cannot catch, common resources like the conch tend to be overharvested.

The problem of overharvesting common resources is not a new one, but ecologist Garret Hardin put the tag “Tragedy of the Commons” to the problem in a 1968 article in the magazine Science. Economists view this as a problem of property rights. Since nobody owns the ocean, or the conch that crawl on the sand beneath it, no one individual has an incentive to protect that resource and responsibly harvest it. To address the issue of overharvesting conch and other marine fisheries, economists typically advocate simple devices like fishing licenses, harvest limits, and shorter fishing seasons. When the population of a species drops to critically low numbers, governments have even banned the harvest until biologists determine that the population has returned to sustainable levels. In fact, such is the case with the conch, the harvesting of which has been effectively banned in the United States since 1986.

Visit this website for more on the queen conch industry:

www.fishwatch.gov/seafood_profiles/species/conch/species_pages/queen_conch.htm

Positive Externalities in Public Health Programs

One of the most remarkable changes in the standard of living in the last several centuries is that people are living longer. Thousands of years ago, human life expectancy is believed to have been in the range of 20 to 30 years. By 1900, average life expectancy in the United States was 47 years. By the start of the twenty-first century, U.S. life expectancy was 77 years. Most of the gains in life expectancy in the history of the human race happened in the twentieth century.

The rise in life expectancy seems to stem from three primary factors. First, systems for providing clean water and disposing of human waste helped to prevent the transmission of many diseases. Second, changes in public behavior have advanced health. Early in the twentieth century, for example, people learned the importance of boiling bottles before using them for food storage and baby’s milk, washing their hands, and protecting food from flies. More recent behavioral changes include reducing the number of people who smoke tobacco and precautions to limit sexually transmitted diseases. Third, medicine has played a large role. Immunizations for diphtheria, cholera, pertussis, tuberculosis, tetanus, and yellow fever were developed between 1890 and 1930. Penicillin, discovered in 1941, led to a series of other antibiotic drugs for bringing infectious diseases under control. In recent decades, drugs that reduce the risks of high blood pressure have had a dramatic effect in extending lives.

These advances in public health have all been closely linked to positive externalities and public goods. Public health officials taught hygienic practices to mothers in the early 1900s and encouraged less smoking in the late 1900s. Many public sanitation systems and storm sewers were funded by government because they have the key traits of public goods. In the twentieth century, many medical discoveries came out of government or university-funded research. Patents and intellectual property rights provided an additional incentive for private inventors. The reason for requiring immunizations, phrased in economic terms, is that it prevents spillovers of illness to others—as well as helping the person immunized.

Funding Innovation

If the private sector does not have sufficient incentive to carry out research and development, one possibility is for the government to fund such work directly. Government spending can provide direct financial support for research and development (R&D) done at colleges and universities, nonprofit research entities, and sometimes by private firms, as well as at government-run laboratories. While government spending on research and development produces technology that is broadly available for firms to use, it costs taxpayers money and can sometimes be directed more for political than for scientific or economic reasons.

The first column of Table shows the sources of total U.S. spending on research and development; the second column shows the total dollars of R&D funding by each source. The third column shows that, relative to the total amount of funding, 26% comes from the federal government, about 67% of R&D is done by industry, and less than 3% is done by universities and colleges.

| Sources of R&D Funding | Amount ($ billions) | Percent of the Total |

| Federal government | $103.7 | 26.08% |

| Industry | $267.8 | 67.35% |

| Universities and colleges | $10.6 | 2.67% |

| Nonprofits | $12 | 3.02% |

| Nonfederal government | $3.5 | 0.88% |

In the 1960s the federal government paid for about two-thirds of the nation’s R&D. Over time, the U.S. economy has come to rely much more heavily on industry-funded R&D. The federal government has tried to focus its direct R&D spending on areas where private firms are not as active. One difficulty with direct government support of R&D is that it inevitably involves political decisions about which projects are worthy. The scientific question of whether research is worthwhile can easily become entangled with considerations like the location of the congressional district in which the research funding is being spent.

Visit the NASA website http://www.nasa.gov/ and the USDA website http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/usdahome?navid=conservation to read about government research that would not take place without government support.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.Self Check Questions

- What is a trust?

- Identify at least 4 pieces of anti-monopoly legislation.

- Are all monopolies bad? Explain and justify your answer.

- Use the internet to find at least 12 regulatory agencies established by the U.S. government since 1906. Identify what they do and why they are important.

- Identify 3 ways the internet is used by consumers, by companies, and by the government in relation to the economy.

- Explain how the U.S. economy has evolved to a "modified free enterprise economy".

| Image | Reference | Attributions |

|

[Figure 1] | Credit: OpenStax College Source: https://cnx.org/contents/aWGdK2jw@11.73:HfomLAPm@5/How-Governments-Can-Encourage-Innovation#CNX_Econ_C13_003 License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |