3.3: Business Growth and Expansion

- Page ID

- 6813

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Business Growth and Expansion

A corporate merger involves two private firms joining together. An acquisition refers to one firm buying another firm. In either case, two formerly independent firms become one firm. Antitrust laws seek to ensure active competition in markets, sometimes by preventing large firms from forming through mergers and acquisitions, sometimes by regulating business practices that might restrict competition, and sometimes by breaking up large firms into smaller competitors.

Universal Generalizations

- Businesses can grow by reinvesting their profits into new plants, equipment and people.

- Business mergers can be both positive and negative.

- Multinationals can introduce opportunities in foreign nations.

Guiding Questions

- How can reinvestment lead to economic growth?

- Explain how mergers can lead to a stronger industry?

- Discuss the reasons for mergers, as well as the positive and negative aspects of mergers.

Reinvesting

A business can grow through reinvesting a portion of its profits, by improving or adding to its factories, hiring additional labor, or purchasing technology. The cash flow, or the real measure of a business’s profits, can help to produce additional products through reinvestment, which in turn can generate additional sales and a larger cash flow during the next sales period. As long as the company remains profitable, and as long as the reinvested cash flow is larger than the depreciation (wear and tear) on the equipment, the company will continue to grow.

Video: What are Mergers and Acquisitions?

Mergers

Another method of expanding a company is to have it merge with another firm to form a single large corporation. There are several reasons why companies may merge: 1) to make the company larger (2) to become more efficient (3) to acquire a new product line (4) to catch up or even eliminate their rivals and finally (5) to lose its corporate identity.

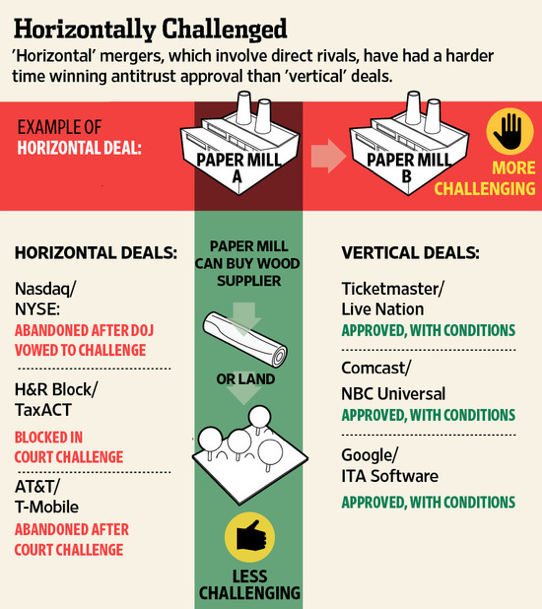

(Source: http://cdn.theatlantic.com/static/mt/assets/business/WSJ_Screen_Shot.png)

Types of Mergers

There are two types of mergers. The first type is known as a horizontal merger which occurs when two or more firms that produce the same kind of product join together. A company may do this to grow larger, to become more efficient, to acquire new product lines, to eliminate a rival, or to lose its corporate identity.

The second kind of merger is a vertical merger which involves different steps of manufacturing. These companies join together to protect themselves against the possible loss of suppliers and streamline the manufacturing process.

Another type of merger is known as a conglomerate, which is a firm that owns at least four businesses that make unrelated products. The companies that are a part of the conglomerate make it possible for the corporation to protect itself through diversification. If one company in the conglomerate is not doing as well in the marketplace, the other companies may be able to help protect the rest of the conglomerate's profits.

Corporate Mergers

A corporate merger occurs when two formerly separate firms combine to become a single firm. When one firm purchases another it is called an acquisition. An acquisition may not look like a simple merger, since the newly purchased firm may continue to be operated under its former company name. Mergers can also be lateral, where two firms of similar sizes combine to become one. However, both mergers and acquisitions lead to two formerly separate firms being under common ownership, and so they are commonly grouped together.

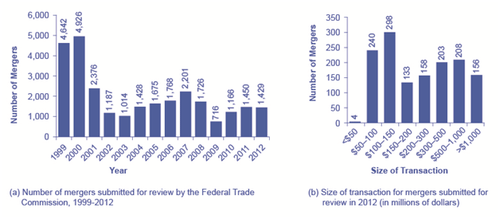

Since a merger combines two firms into one, it can reduce the extent of competition between firms. Therefore, when two U.S. firms announce a merger or acquisition where at least one of the firms is above a minimum size of sales (a threshold that moves up gradually over time, and was at $70.9 million in 2013), or certain other conditions are met, they are required under law to notify the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The left-hand panel of Figure 2 (a) shows the number of mergers submitted for review to the FTC each year from 1999 to 2012. Mergers were very high in the late 1990s, diminished in the early 2000s, and then rebounded somewhat in a cyclical fashion. The right-hand panel of Figure 2 (b) shows the distribution of those mergers submitted for review in 2012 as measured by the size of the transaction. It is important to remember that this total leaves out many small mergers under $50 million, which only need to be reported in certain limited circumstances. About a quarter of all reported merger and acquisition transactions in 2012 exceeded $500 million, while about 11 percent exceeded $1 billion.

Figure 2 (a) The number of mergers in 1999 and 2000 were relatively high compared to the annual numbers seen from 2001–2012. While 2001 and 2007 saw a high number of mergers, these were still only about half the number of mergers in 1999 and 2000. (b) In 2012, the greatest number of mergers submitted for review was for transactions between $100 and $150 million.

The laws that gives the government the power to block certain mergers, and even in some cases to break up large firms into smaller ones, are called antitrust laws. Before a large merger happens, the antitrust regulators at the FTC and the U.S. Department of Justice can allow the merger, prohibit it, or allow it if certain conditions are met. One common condition is that the merger will be allowed if the firm agrees to sell off certain parts. For example, in 2006, Johnson & Johnson bought Pfizer’s “consumer health” division, which included well-known brands like Listerine mouthwash and Sudafed cold medicine. As a condition of allowing the merger, Johnson & Johnson was required to sell off six brands to other firms, including Zantac® heartburn relief medication, Cortizone anti-itch cream, and Balmex diaper rash medication, to preserve a greater degree of competition in these markets.

The U.S. government approves most proposed mergers. In a market-oriented economy, firms have the freedom to make their own choices. Private firms generally have the freedom to:

- expand or reduce production

- set the price they choose

- open new factories or sales facilities or close them

- hire workers or to lay them off

- start selling new products or stop selling existing ones

If the owners want to acquire a firm or be acquired, or to merge with another firm, this decision is just one of many that firms are free to make. In these conditions, the managers of private firms will sometimes make mistakes. They may close down a factory which, it later turns out, would have been profitable. They may start selling a product that ends up losing money. A merger between two companies can sometimes lead to a clash of corporate personalities that makes both firms worse off. But the fundamental belief behind a market-oriented economy is that firms, not governments, are in the best position to know if their actions will lead to attracting more customers or producing more efficiently.

Indeed, government regulators agree that most mergers are beneficial to consumers. As the Federal Trade Commission has noted on its website (as of November, 2013): “Most mergers actually benefit competition and consumers by allowing firms to operate more efficiently.” At the same time, the FTC recognizes, “Some [mergers] are likely to lessen competition. That, in turn, can lead to higher prices, reduced availability of goods or services, lower quality of products, and less innovation. Indeed, some mergers create a concentrated market, while others enable a single firm to raise prices.” The challenge for the antitrust regulators at the FTC and the U.S. Department of Justice is to figure out when a merger may hinder competition. This decision involves both numerical tools and some judgments that are difficult to quantify. The following Clear It Up helps explain how antitrust laws came about.

Clear It Up: What is U.S. Antitrust Law?

In the closing decades of the 1800s, many industries in the U.S. economy were dominated by a single firm that had most of the sales for the entire country. Supporters of these large firms argued that they could take advantage of economies of scale and careful planning to provide consumers with products at low prices. However, critics pointed out that when the competition was reduced, these firms were free to charge more and make permanently higher profits, and that without the goading of competition, it was not clear that they were as efficient or innovative as they could be.

In many cases, these large firms were organized in the legal form of a “trust,” in which a group of formerly independent firms were consolidated together by mergers and purchases, and a group of “trustees” then ran the companies as if they were a single firm. Thus, when the U.S. government passed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890 to limit the power of these trusts, it was called an antitrust law. In an early demonstration of the law’s power, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1911 upheld the government’s right to break up Standard Oil, which had controlled about 90% of the country’s oil refining, into 34 independent firms, including Exxon, Mobil, Amoco, and Chevron. In 1914, the Clayton Antitrust Act outlawed mergers and acquisitions (where the outcome would be to “substantially lessen competition” in an industry), price discrimination (where different customers are charged different prices for the same product), and tied sales (where purchase of one product commits the buyer to purchase some other product). Also in 1914, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was created to define more specifically what competition was unfair. In 1950, the Celler-Kefauver Act extended the Clayton Act by restricting vertical and conglomerate mergers. In the twenty-first century, the FTC and the U.S. Department of Justice continue to enforce antitrust laws.

New Directions for Antitrust

Defining a market is often controversial. For example, Microsoft in the early 2000s had a dominant share of the software for computer operating systems. However, in the total market for all computer software and services, including everything from games to scientific programs, the Microsoft share was only about 16% in 2000. A narrowly defined market will tend to make concentration appear higher, while a broadly defined market will tend to make it appear smaller.

There are two especially important shifts affecting how markets are defined in recent decades: one centers on technology and the other centers on globalization. In addition, these two shifts are interconnected. With the vast improvement in communications technologies, including the development of the Internet, a consumer can order books or pet supplies from all over the country or the world. As a result, the degree of competition many local retail businesses face has increased. The same effect may operate even more strongly in markets for business supplies, where so-called “business-to-business” websites can allow buyers and suppliers from anywhere in the world to find each other.

Globalization has changed the boundaries of markets. Now, many industries find that their competition comes from the global market. A few decades ago, three companies, General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler, dominated the U.S. auto market. By 2007, however, these three firms were making less than half of U.S. auto sales, and facing competition from well-known car manufacturers such as Toyota, Honda, Nissan, Volkswagen, Mitsubishi, and Mazda.

Because attempting to define a particular market can be difficult and controversial, the Federal Trade Commission has begun to look less at market share and more at the data on actual competition between businesses. For example, in February 2007, Whole Foods Market and Wild Oats Market announced that they wished to merge. These were the two largest companies in the market that the government defined as “premium natural and organic supermarket chains.” However, one could also argue that they were two relatively small companies in the broader market for all stores that sell groceries or specialty food products.

Rather than relying on a market definition, the government antitrust regulators looked at detailed evidence on profits and prices for specific stores in different cities, both before and after other competitive stores entered or exited. Based on that evidence, the Federal Trade Commission decided to block the merger. After two years of legal battles, the merger was eventually allowed in 2009 under the conditions that Whole Foods sell off the Wild Oats brand name and a number of individual stores to preserve competition in certain local markets.

This new approach to antitrust regulation involves detailed analysis of specific markets and companies, instead of defining a market and counting up total sales. A common starting point is for antitrust regulators to use statistical tools and real-world evidence to estimate the demand curves and supply curves faced by the firms that are proposing the merger. A second step is to specify how competition occurs in this specific industry. Some possibilities include competing to cut prices, to raise output, to build a brand name through advertising, and to build a reputation for good service or high quality. With these pieces of the puzzle in place, it is then possible to build a statistical model that estimates the likely outcome for consumers if the two firms are allowed to merge. Of course, these models do require some degree of subjective judgment, so they can become the subject of legal disputes between the antitrust authorities and the companies that wish to merge.

Regulating Anticompetitive Behavior

The U.S. antitrust laws reach beyond blocking mergers that would reduce competition to include a wide array of anticompetitive practices. For example, it is illegal for competitors to form a cartel that colludes to make pricing and output decisions as if they were a monopoly firm. The Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice prohibit firms from agreeing to fix prices or output, rigging bids, or sharing or dividing markets by allocating customers, suppliers, territories, or lines of commerce.

In the late 1990s, for example, the antitrust regulators prosecuted an international cartel of vitamin manufacturers that included the Swiss firm Hoffman-La Roche, the German firm BASF, and the French firm Rhone-Poulenc. These firms reached agreements on how much to produce, how much to charge, and which firm would sell to which customers. The high-priced vitamins were then bought by firms like General Mills, Kellogg, Purina-Mills, and Proctor and Gamble, which pushed up the prices more. Hoffman-La Roche pleaded guilty in May 1999 and agreed both to pay a fine of $500 million and to have at least one top executive serve four months of jail time.

Under U.S. antitrust laws, a monopoly itself is not illegal. If a firm has a monopoly because of a newly patented invention, for example, the law explicitly allows a firm to earn higher-than-normal profits for a time as a reward for innovation. If a firm achieves a large share of the market by producing a better product at a lower price this behavior is not prohibited by antitrust law.

Restrictive Practices

Antitrust laws include rules against restrictive practices—practices that do not involve outright agreements to raise price or to reduce the quantity produced, but that might have the effect of reducing competition. Antitrust cases involving restrictive practices are often controversial because they delve into specific contracts or agreements between firms that are allowed in some cases but not in others.

For example, if a product manufacturer is selling to a group of dealers who then sell to the general public it is illegal for the manufacturer to demand a minimum resale price maintenance agreement, which would require the dealers to sell for at least a certain minimum price. A minimum price contract is illegal because it would restrict competition among dealers. However, the manufacturer is legally allowed to “suggest” minimum prices and to stop selling to dealers who regularly undercut the suggested price. If you think this rule sounds like a fairly subtle distinction, you are right.

An exclusive dealing agreement between a manufacturer and a dealer can be legal or illegal. It is legal if the purpose of the contract is to encourage competition between dealers. For example, it is legal for the Ford Motor Company to sell its cars to only Ford dealers, for General Motors to sell to only GM dealers, and so on. However, exclusive deals may also limit competition. If one large retailer obtained the exclusive rights to be the sole distributor of televisions, computers, and audio equipment made by a number of companies, then this exclusive contract would have an anticompetitive effect on other retailers.

Tying sales happen when a customer is required to buy one product only if the customer also buys a second product. Tying sales are controversial because they force consumers to purchase a product that they may not actually want or need. Further, the additional, required products are not necessarily advantageous to the customer. Suppose that to purchase a popular DVD, the store required that you also purchase a portable TV of a certain model. These products are only loosely related, thus there is no reason to make the purchase of one contingent on the other. Even if a customer was interested in a portable TV, the tying to a particular model prevents the customer from having the option of selecting one from the numerous types available in the market. A related, but not identical, concept is called bundling, where two or more products are sold as one. Bundling typically offers an advantage for the consumer by allowing them to acquire multiple products or services for a better price. For example, several cable companies allow customers to buy products like cable, internet, and a phone line through a special price available through bundling. Customers are also welcome to purchase these products separately, but the price of bundling is usually more appealing.

In some cases, tying sales and bundling can be viewed as anticompetitive. However, in other cases, they may be legal and even common. It is common for people to purchase season tickets to a sports team or a set of concerts so that they can be guaranteed tickets to the few contests or shows that are most popular and likely to sell out. Computer software manufacturers may often bundle a number of different programs even when the buyer only wants a few of the programs. Think about the software that is included in a new computer purchase, for example.

Recall that predatory pricing occurs when the existing firm (or firms) reacts to a new firm by dropping prices very low until the new firm is driven out of the market, at which point the existing firm raises prices again. This pattern of pricing is aimed at deterring the entry of new firms into the market. In practice, it can be hard to figure out when pricing should be considered predatory. Say that American Airlines is flying between two cities, and a new airline starts flying between the same two cities at a lower price. If American Airlines cuts its price to match the new entrant, is this predatory pricing? Or is it just market competition at work? A commonly proposed rule is that if a firm is selling for less than its average variable cost—that is, at a price where it should be shutting down—then there is evidence for predatory pricing. Calculating in the real world what costs are variable and what costs are fixed is often not obvious, either.

Case Study: Did Microsoft® engage in anticompetitive and restrictive practices?

The most famous restrictive practices case of recent years was a series of lawsuits by the U.S. government against Microsoft—lawsuits that were encouraged by some of Microsoft’s competitors. All sides admitted that Microsoft’s Windows program had a near-monopoly position in the market for the software used in general computer operating systems. All sides agreed that the software had many satisfied customers. All sides agreed that the capabilities of computer software that was compatible with Windows—both software produced by Microsoft and that produced by other companies—had expanded dramatically in the 1990s. Having a monopoly or a near-monopoly is not necessarily illegal in and of itself, but in cases where one company controls a great deal of the market, antitrust regulators look at any allegations of restrictive practices with special care.

The antitrust regulators argued that Microsoft had gone beyond profiting from its software innovations and its dominant position in the software market for operating systems, and it had tried to use its market power in operating systems software to take over other parts of the software industry. For example, the government argued that Microsoft had engaged in an anticompetitive form of exclusive dealing by threatening computer makers that, if they did not leave another firm’s software off their machines (specifically, Netscape’s Internet browser), then Microsoft would not sell them its operating system software. Microsoft was accused by the government antitrust regulators of tying together its Windows operating system software where it had a monopoly, with its Internet Explorer browser software, where it did not have a monopoly, and thus using this bundling as an anticompetitive tool. Microsoft was also accused of a form of predatory pricing; namely, giving away certain additional software products for free as part of Windows. This was a way of driving out the competition from other makers of the software.

In April 2000, a federal court held that Microsoft’s behavior had crossed the line into unfair competition, and recommended that the company be broken into two competing firms. However, that penalty was overturned on appeal. In November 2002 Microsoft reached a settlement with the government that it would end its restrictive practices.

The concept of restrictive practices is continually evolving as firms seek new ways to earn profits and government regulators define what is permissible and what is not. A situation where the law is evolving and changing is always somewhat troublesome since laws are most useful and fair when firms know what they are in advance. In addition, since the law is open to interpretation, competitors who are losing out in the market can accuse successful firms of anticompetitive restrictive practices and try to win through government regulation what they have failed to accomplish in the market. Officials at the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice are, of course, aware of these issues, but there is no easy way to resolve them.

To read more about the anticompetitive practices associated with Microsoft in the early 2000s, read the following articles:

U.S. v. Microsoft Proved That Antitrust Can Keep Tech Power in Check

Video: What is a Multinational Corporation?

Multinationals

When a large corporation has manufacturing or service companies in various countries it becomes known as a multinational. These companies become a part of the country’s GDP, circular flow, and business cycle. They are subject to the laws, taxes, customs, and culture of the various nations where they do business. Multinationals can be both a blessing and a curse to various nations.

| Multinationals | |

| Positive |

|

| Negative |

|

Summary

A corporate merger involves two private firms joining together. An acquisition refers to one firm buying another firm. In either case, two formerly independent firms become one firm. Antitrust laws seek to ensure active competition in markets, sometimes by preventing large firms from forming through mergers and acquisitions, sometimes by regulating business practices that might restrict competition, and sometimes by breaking up large firms into smaller competitors.

The forces of globalization and new communications and information technology have increased the level of competition faced by many firms by increasing the amount of competition from other regions and countries.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.Self Check Questions

- How can a firm generate additional funds to grow and expand?

- What are the five reasons firms may merge?

- What is the difference between a horizontal and vertical merger?

- What is a conglomerate?

- What is a multinational? Which companies are multinational? What are the most positive and negative aspects of a multinational?

- Look up 5 corporations and determine if they are multinationals. List which countries they operate in.

- Use the internet to research a multinational. Determine if it is a positive or negative influence on the country that it is currently operating in.

- Use the internet to search for companies that have recently merged. What type of merger was it? Why did they merge? What will happen to the company now? Are there any negative consequences to the merger? Did the government have to approve the merger?