4.3: Federal Government Expenditures

- Page ID

- 6939

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Federal Government Expenditures

The President, as the head of the Executive Branch of the federal government, determines the direction of fiscal policy. With the help of economic advisers, the Office of Management and Budget, and Congressional support, the President outlines where and how spending should occur. The President's office creates a federal budget or an annual plan for proposed revenues (taxes) and expenditures (spending) for the next year. After the budget is developed it is sent to the Congress. The Congress does have the power to determine whether or not to follow the President's suggested annual budget.

Universal Generalizations

- The federal government must approve spending before revenues can be released.

- The federal government’s budget supplies money for many services and programs.

- The taxes collected by the federal government are used to pay for various federal services and programs.

- State and local governments benefit from federal expenditures.

Guiding Questions

- How would the U.S. economy be impacted if the federal government did not pay for various services and programs that benefit both the states and the local governments?

- Could state and local governments get along without revenues from the federal government?

- What does the federal government have to do to if does not collect enough revenues to cover its expenditures?

- What is the purpose of a balanced budget amendment?

- Name three aspects of federal spending that you benefit from directly.

The Federal Budget

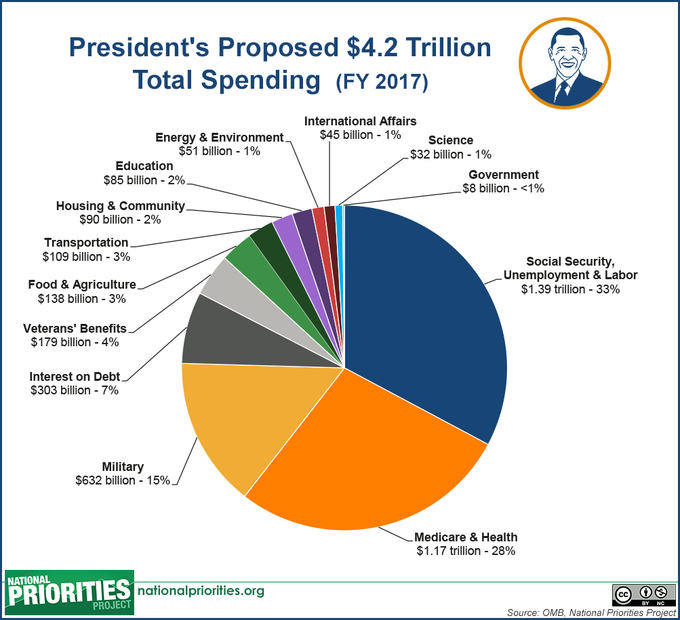

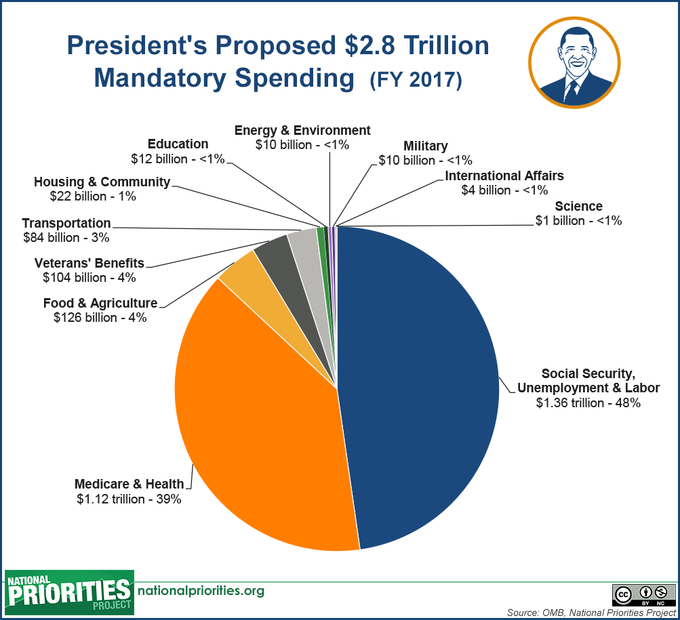

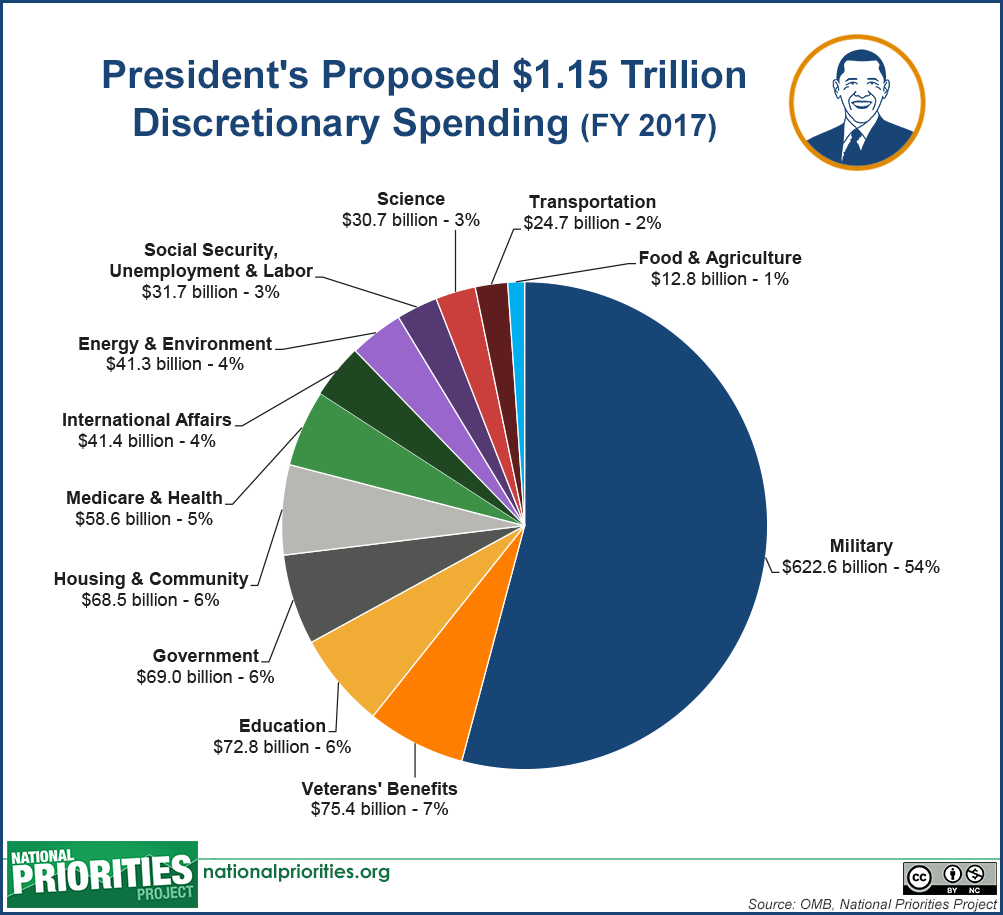

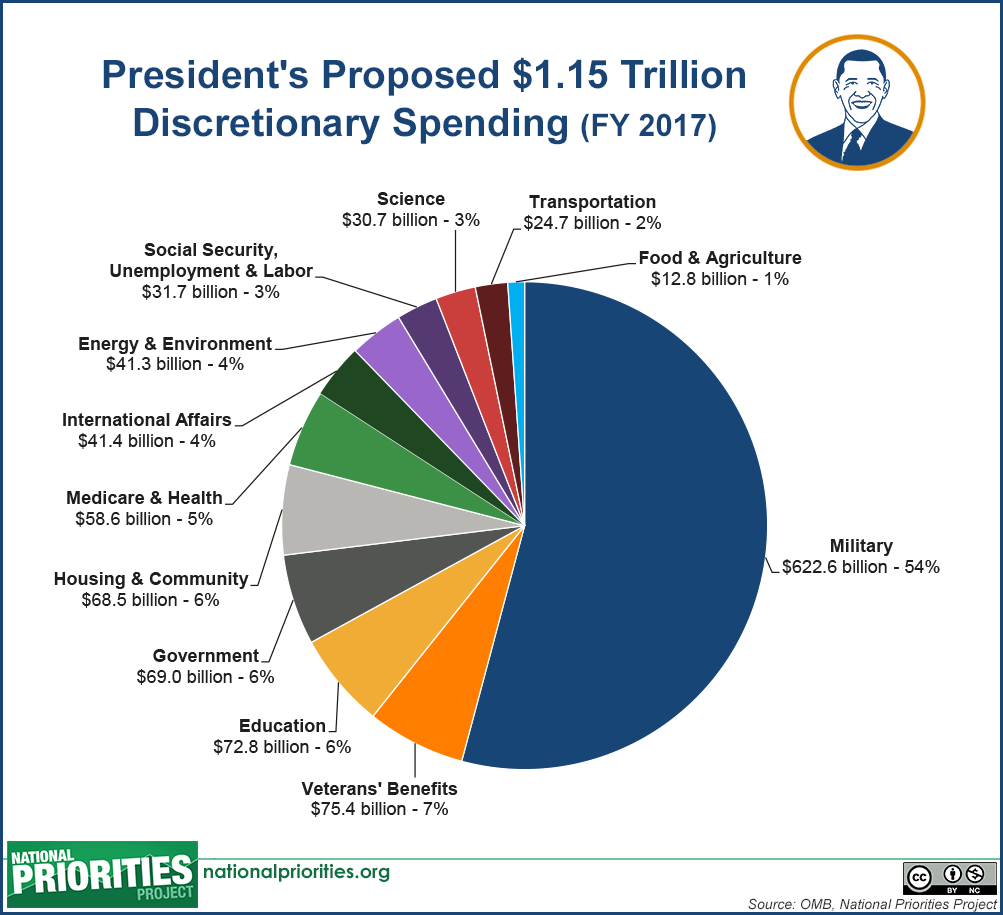

The largest portion of the annual budget is made up of mandatory spending, or spending that is authorized by law and continues without the need of further approval by Congress. Examples of mandatory spending would be Social Security, Medicare, and interest on the U.S. debt. The other portion of the budget is discretionary spending, or spending money that needs annual authorization. This type of spending is what is most often argued over by members of the legislative branch. Some members may believe that there should be more spending for a particular program, while other members of Congress may believe that spending should be cut to help provide spending for other programs. Each year discretionary spending can be increased, kept the same, or cut based on projected needs of the programs or specific departments and agencies. Examples of areas of discretionary spending are military bases, the U.S. Coast Guard, Customs and Border Protection, welfare, or assistance to farmers.

Video: 2017 Budget Proposals vs. Americans' Priorities

Every year the President of the United States establishes a general budget for multiple years beginning with the first year that he takes office. The president consults with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), his Council of Economic Advisors, the heads of all Cabinet Departments, various agencies and others to determine how and where money should be budgeted for the next fiscal year. The federal budget is prepared for a "fiscal year" which begins on October 1 and ends on September 30 the following year. The budget must take into account whether or not there is a projected "surplus" (which can occur if there are more taxes collected than will be spent on programs) or if there is to be a "deficit" (which means that there will be more money spent on programs during the year than collected in taxes).

Once the President has outlined his budget, by law it must be presented to the Congress. The Congress actually "holds the purse strings" and can follow the president's budget or make any changes it sees fit. The House of Representatives examines the discretionary spending by setting targets for how much to spend or cut based on the previous year's spending. Once targets are agreed on, various House of Representatives committees meet to determine "appropriations" or how much money federal agencies will need for specific purposes. The House holds committee hearings, debates spending, and asks experts for their opinions on why funding for programs should be increased or decreased in the next year. Once all of the committees have figured out the funding for their specific portions of the budget, the House of Representatives reconvenes to vote on the complete budget. From the House of Representatives, the proposed budget is sent to the Senate. The Senate may approve the bill sent over by the House of Representatives, or it may draft its own version of the budget. If there are any differences in the two versions of the budget, the House of Representatives and the Senate create a conference committee to work out a compromise bill.

After both the House of Representatives and the Senate have agreed on a budget, it is sent back to the President. The President may not even recognize the bill that he originally sent to the Congress since they have the power to actually create the budget as they see fit. If the budget is too different from the one he sent, he can veto it and send it back to Congress to consider making revisions to the budget. If Congress refuses, they can pass the budget without the President's signature if 2/3 of both houses of Congress agree; however that is usually very difficult to accomplish. Generally, the budgets from one year to the next are very similar with only minor changes. Once signed by the President, the budget becomes law.

To view a copy of the Executive Branch's 2018 Budget visit Budget of the U.S. Government.

If the budget is not correctly anticipated, or if the Congress and the President cannot reach an agreement on the budget, the federal government can run out of money. This would mean that the government would have to furlough federal employees without pay or close non-essential departments. In both 1995, and 1995–96, the United States federal government had to shut down due to budget conflicts between President Clinton and the Congress over annual funding for various programs such as public health, education, Medicare, and the environment. The president disagreed with the spending cuts, he vetoed the annual bill, and the government shut down. Federal workers were told not to report for work, or furloughed, and several non-essential departments and agencies were closed from November 14 -19, 1995, and from December 16, 1995, -January 6, 1996, for a total of 27 days.

The government “shut down” not only impacted federal employees but also impacted other areas such as: services for military veterans, the Centers for Disease Control, toxic waste cleanup stopped, all of the 368 National Parks were closed, and no applications for passports or visas were processed.

You may ask yourself how many times has this occurred? The answer is 17 times since 1976. To read more about government shutdowns, or "spending gaps" visit this article by The Washington Post called Here is Every Previous Government Shutdown: Why They Happened and How They Ended.

Source: https://media.nationalpriorities.org/uploads/2017_pres_budget_disc_spending_pie_large.png

Source: https://www.nationalpriorities.org/analysis/2016/presidents-2017-budget-in-pictures/

To read more about the 2017 Federal Spending by the Federal Government, visit Federal Spending: Where Does the Money Go.

The largest portion of mandatory spending over the last several decades has been in Social Security, followed by Medicare and health care. Clearly as the U.S. population ages and lives longer, more and more spending will be directed toward these two areas. The largest portion of discretionary spending since the end of World War II has been directed at the military and will remain at this level while the U.S. engages in the Global War on Terrorism.

Visit the following link to read an article about the history of taxing and spending in the U.S.: A Short History of Government Taxing and Spending in the United States.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.Self Check Questions

- What is a federal budget? What are two main categories of the federal budget?

- What is mandatory spending? Give 3 examples.

- What is discretionary spending? Give 3 examples.

- Go online and look up the budget for the next fiscal year. What categories have the highest amount of spending? Why?

- Define federal budget surplus and federal budget deficit.

- Go online and determine if the next fiscal year is projected to have a surplus or a deficit. How much will it be? Why are they projecting this situation?

- Which part of the federal government begins the budget process?

- What is an appropriations bill?

| Image | Reference | Attributions |

|

[Figure 1] | Source: https://media.nationalpriorities.org/uploads/2017_pres_budget_disc_spending_pie_large.png License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |

|

[Figure 2] | Source: https://media.nationalpriorities.org/uploads/2017_pres_budget_disc_spending_pie_large.png License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |