5.9: Investment Strategies and Financial Assets

- Page ID

- 1729

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Investment Strategies & Financial Assets

Firms often make decisions that involve spending money in the present and expecting to earn profits in the future. Examples include when a firm buys a machine that will last 10 years, or builds a new plant that will last for 30 years, or starts a research and development project. Firms can raise the financial capital they need to pay for such projects in four main ways:

- early-stage investors;

- by reinvesting profits;

- borrowing through banks or bonds; and

- selling stock.

When owners of a business choose sources of financial capital, they also choose how to pay for them.

Universal Generalizations

- It is important to consider several factors when you invest in financial assets.

- To invest wisely, investors must identify their goals and analyze the risk and return involved.

- When the government or corporations need to borrow funds for a long period of time, they often issue bonds.

- Investors often refer to markets according to the characteristics of the financial assets traded in them.

Guiding Questions

- How does a 401(k) plan work?

- Explain how current yields are computed.

- Analyze the risk involved in different types of financial assets.

- What considerations are important to investors in the financial market?

Early Stage Financial Capital

Firms that are just beginning often have an idea or a prototype for a product or service to sell, but few customers, or even no customers at all, and thus are not earning profits. Such firms face a difficult problem when it comes to raising financial capital: How can a firm that has not yet demonstrated any ability to earn profits pay a rate of return to financial investors?

For many small businesses, the original source of money is the owner of the business. Someone who decides to start a restaurant or a gas station, for instance, might cover the startup costs by dipping into his or her own bank account, or by borrowing money (perhaps using a home as collateral). Alternatively, many cities have a network of well-to-do individuals, known as “angel investors,” who will put their own money into small new companies at an early stage of development in exchange for owning some portion of the firm.

Venture capital firms make financial investments in new companies that are still relatively small in size, but that have potential to grow substantially. These firms gather money from a variety of individual or institutional investors, including banks, institutions like college endowments, insurance companies that hold financial reserves, and corporate pension funds. Venture capital firms do more than just supply money to small startups. They also provide advice on potential products, customers, and key employees. Typically, a venture capital fund invests in a number of firms, and then investors in that fund receive returns according to how the fund as a whole performs.

The amount of money invested in venture capital fluctuates substantially from year to year: as an example, venture capital firms invested more than $27 billion in 2012, according to the National Venture Capital Association. All early-stage investors realize that the majority of small startup businesses will never hit it big; indeed, many of them will go out of business within a few months or years. They also know that getting in on the ground floor of a few huge successes like a Netflix or an Amazon.com can make up for a lot of failures. Early-stage investors are therefore willing to take large risks in order to be in a position to gain substantial returns on their investment.

Profits as a Source of Financial Capital

If firms are earning profits (their revenues are greater than costs), they can choose to reinvest some of these profits in equipment, structures, and research and development. For many established companies, reinvesting their own profits is one primary source of financial capital. Companies and firms just getting started may have numerous attractive investment opportunities, but few current profits to invest. Even large firms can experience a year or two of earning low profits or even suffering losses. Unless the firm can find a steady and reliable source of financial capital so that it can continue making real investments in tough times, the firm may not survive until better times arrive. Firms often need to find sources of financial capital other than profits.

Borrowing: Banks and Bonds

When a firm has a record of at least earning significant revenues, and better still of earning profits, the firm can make a credible promise to pay interest, and so it becomes possible for the firm to borrow money. Firms have two main methods of borrowing: banks and bonds.

A bank loan for a firm works in much the same way as a loan for an individual who is buying a car or a house. The firm borrows an amount of money and then promises to repay it, including some rate of interest, over a predetermined period of time. If the firm fails to make its loan payments, the bank (or banks) can often take the firm to court and require it to sell its buildings or equipment to make the loan payments.

Another source of financial capital is a bond. A bond is a financial contract: a borrower agrees to repay the amount that was borrowed and also a rate of interest over a period of time in the future. A corporate bond is issued by firms, but bonds are also issued by various levels of government. For example, a municipal bond is issued by cities, a state bond by U.S. states, and a Treasury bond by the federal government through the U.S. Department of the Treasury. A bond specifies an amount that will be borrowed, the interest rate that will be paid, and the time until repayment.

For example, a large company might issue bonds for $10 million; the firm promises to make interest payments at an annual rate of 8%, or $800,000 per year and then, after 10 years, will repay the $10 million it originally borrowed. When a firm issues bonds, the total amount that is borrowed is divided up. If a firm seeks to borrow $50 million by issuing bonds, it might actually issue 10,000 bonds of $5,000 each. In this way, an individual investor could, in effect, loan the firm $5,000, or any multiple of that amount. Anyone who owns a bond and receives the interest payments is called a bondholder. If a firm issues bonds and fails to make the promised interest payments, the bondholders can take the firm to court and require it to pay, even if the firm needs to raise the money by selling buildings or equipment. However, there is no guarantee the firm will have sufficient assets to pay off the bonds. The bondholders may get back only a portion of what they loaned the firm.

Bank borrowing is more customized than issuing bonds, so it often works better for relatively small firms. The bank can get to know the firm extremely well—often because the bank can monitor sales and expenses quite accurately by looking at deposits and withdrawals. Relatively large and well-known firms often issue bonds instead. They use bonds to raise new financial capital that pays for investments or to raise capital to pay off old bonds, or to buy other firms. However, the idea that banks are usually used for relatively smaller loans and bonds for larger loans is not an ironclad rule: sometimes groups of banks make large loans and sometimes relatively small and lesser-known firms issue bonds.

Corporate Stock and Public Firms

A corporation is a business that “incorporates”—that is owned by shareholders that have limited liability for the debt of the company but share in its profits (and losses). Corporations may be private or public, and they may or may not have stock that is publicly traded. They may raise funds to finance their operations or new investments by raising capital through the sale of stock or the issuance of bonds.

Those who buy the stock become the owners, or shareholders, of the firm. Stock represents ownership of a firm; that is, a person who owns 100% of a company’s stock, by definition, owns the entire company. The stock of a company is divided into shares. Corporate giants like IBM, AT&T, Ford, General Electric, Microsoft, Merck, and Exxon all have millions of shares of stock. In most large and well-known firms, no individual owns a majority of the shares of the stock. Instead, large numbers of shareholders—even those who hold thousands of shares—each have only a small slice of the overall ownership of the firm.

When a company is owned by a large number of shareholders, there are three questions to ask: How and when does the company get money from the sale of its stock? What rate of return does the company promise to pay when it sells stock? Who makes decisions in a company owned by a large number of shareholders?

First, a firm receives money from the sale of its stock only when the company sells its own stock to the public (the public includes individuals, mutual funds, insurance companies, and pension funds). A firm’s first sale of stock to the public is called an initial public offering (IPO). The IPO is important for two reasons. For one, the IPO and any stock issued thereafter, such as stock held as treasury stock (shares that a company keeps in their own treasury) or new stock issued later as a secondary offering, provides the funds to repay the early-stage investors, like the angel investors and the venture capital firms. A venture capital firm may have a 40% ownership in the firm. When the firm sells stock, the venture capital firm sells its part ownership of the firm to the public. A second reason for the importance of the IPO is that it provides the established company with financial capital for a substantial expansion of its operations.

Most of the time when a corporate stock is bought and sold, however, the firm receives no financial return at all. If you buy shares of stock in General Motors, you almost certainly buy them from the current owner of those shares, and General Motors does not receive any of your money. This pattern should not seem particularly odd. After all, if you buy a house, the current owner gets your money, not the original builder of the house. Similarly, when you buy shares of stock, you are buying a small slice of ownership of the firm from the existing owner—and the firm that originally issued the stock is not a part of this transaction.

Second, when a firm decides to issue stock, it must recognize that investors will expect to receive a rate of return. That rate of return can come in two forms. A firm can make a direct payment to its shareholders, called a dividend. Alternatively, a financial investor might buy a share of stock in Wal-Mart for $45 and then later sell that share of stock to someone else for $60, for a gain of $15. The increase in the value of the stock (or of any asset) between when it is bought and when it is sold is called a capital gain.

Third: Who makes the decisions about when a firm will issue stock, or pay dividends, or re-invest profits? To understand the answers to these questions, it is useful to separate firms into two groups: private and public.

A private company is owned by the people who run it on a day-to-day basis. A private company can be run by individuals, in which case it is called a sole proprietorship, or it can be run by a group, in which case it is a partnership. A private company can also be a corporation, but with no publicly issued stock. A small law firm run by one person, even if it employs some other lawyers, would be a sole proprietorship. A larger law firm may be owned jointly by its partners. Most private companies are relatively small, but there are some large private corporations, with tens of billions of dollars in annual sales, that do not have publicly issued stock, such as farm products dealer Cargill, the Mars candy company, and the Bechtel engineering and construction firm.

When a firm decides to sell stock, which in turn can be bought and sold by financial investors, it is called a public company. Shareholders own a public company. Since the shareholders are a very broad group, often consisting of thousands or even millions of investors, the shareholders' vote for a board of directors, who in turn hire top executives to run the firm on a day-to-day basis. The more shares of stock a shareholder owns, the more votes that shareholder is entitled to cast for the company’s board of directors.

In theory, the board of directors helps to ensure that the firm is run in the interests of the true owners—the shareholders. However, the top executives who run the firm have a strong voice in choosing the candidates who will be on their board of directors. After all, few shareholders are knowledgeable enough or have enough of a personal incentive to spend energy and money nominating alternative members of the board.

How Firms Choose between Sources of Financial Capital

There are clear patterns in how businesses raise financial capital. These patterns can be explained in terms of imperfect information, a situation where buyers and sellers in a market do not both have full and equal information. Those who are actually running a firm will almost always have more information about whether the firm is likely to earn profits in the future than outside investors who provide financial capital.

Any young startup firm is a risk; indeed, some startup firms are only a little more than an idea on paper. The firm’s founders inevitably have better information about how hard they are willing to work, and whether the firm is likely to succeed, than anyone else. When the founders put their own money into the firm, they demonstrate a belief in its prospects. At this early stage, angel investors and venture capitalists try to overcome the imperfect information, at least in part, by knowing the managers and their business plan personally and by giving them advice.

In 2008, Lehman Brothers were the fourth-largest U.S. investment bank, with 25,000 employees. The firm had been in business for 164 years. On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. There are many causes of the Lehman Brothers failure. One area of apparent failure was the lack of oversight by the Board of Directors to keep managers from undertaking excessive risk. Part of the oversight failure, according to Tim Geithner’s April 10, 2010, testimony to Congress, can be attributed to the Executive Compensation Committee’s emphasis on short-term gains without enough consideration of the risks. In addition, according to the court examiner’s report, the Lehman Brother’s Board of Directors paid too little attention to the details of the operations of Lehman Brothers and also had limited financial service experience.

The board of directors, elected by the shareholders, is supposed to be the first line of corporate governance and oversight for top executives. The second institution of corporate governance is the auditing firm hired to go over the financial records of the company and certify that everything looks reasonable. The third institution of corporate governance is outside investors, especially large shareholders like those who invest large mutual funds or pension funds. In the case of Lehman Brothers, corporate governance failed to provide investors with accurate financial information about the firm’s operations.

As a firm becomes at least somewhat established and its strategy appears likely to lead to profits in the near future, knowing the individual managers and their business plans on a personal basis becomes less important because information has become more widely available regarding the company’s products, revenues, costs, and profits. As a result, other outside investors who do not know the managers personally, like bondholders and shareholders, are more willing to provide financial capital to the firm.

At this point, a firm must often choose how to access financial capital. It may choose to borrow from a bank, issue bonds, or issue stock. The great disadvantage of borrowing money from a bank or issuing bonds is that the firm commits to scheduled interest payments, whether or not it has sufficient income. The great advantage of borrowing money is that the firm maintains control of its operations and is not subject to shareholders. Issuing stock involves selling off ownership of the company to the public and becoming responsible to a board of directors and the shareholders.

The benefit of issuing stock is that a small and growing firm increases its visibility in the financial markets and can access large amounts of financial capital for expansion, without worrying about paying this money back. If the firm is successful and profitable, the board of directors will need to decide upon a dividend payout or how to reinvest profits to further grow the company. Issuing and placing stock is expensive, requires the expertise of investment bankers and attorneys, and entails compliance with reporting requirements to shareholders and government agencies, such as the federal Securities and Exchange Commission.

How Households Supply Financial Capital

The ways in which firms would prefer to raise funds are only half the story of financial markets. The other half is what those households and individuals who supply funds desire, and how they perceive the available choices. The focus of our discussion now shifts from firms on the demand side of financial capital markets to households on the supply side of those markets. The mechanisms for saving available to households can be divided into several categories: deposits in bank accounts; bonds; stocks; money market mutual funds; stock and bond mutual funds; and housing and other tangible assets like owning gold. Each of these investments needs to be analyzed in terms of three factors: (1) the expected rate of return it will pay; (2) the risk that the return will be much lower or higher than expected; and (3) the liquidity of the investment, which refers to how easily money or financial assets can be exchanged for a good or service. We will do this analysis as we discuss each of these investments in the sections below. First, however, we need to understand the difference between the expected rate of return, risk, and the actual rate of return.

Expected Rate of Return, Risk, and Actual Rate of Return

The expected rate of return refers to how much a project or an investment is expected to return to the investor, either in future interest payments, capital gains, or increased profitability. It is usually the average return over a period of time, usually in years or even decades. Risk measures the uncertainty of that project’s profitability. There are several types of risk, including default risk and interest rate risk. Default risk, as its name suggests, is the risk that the borrower fails to pay back the bond. Interest rate risk is the danger that you might buy a long term bond at a 6% interest rate right before market rates suddenly raise, so had you waited, you could have gotten a similar bond that paid 9%. A high-risk investment is one for which a wide range of potential payoffs is reasonably probable. A low-risk investment will have actual returns that are fairly close to its expected rate of return year after year. A high-risk investment will have actual returns that are much higher than the expected rate of return in some months or years and much lower in other months or years. The actual rate of return refers to the total rate of return, including capital gains and interest paid on an investment at the end of a period of time.

Bank Accounts

An intermediary is one who stands between two other parties; for example, a person who arranges a blind date between two other people is one kind of intermediary. In financial capital markets, banks are an example of a financial intermediary—that is, an institution that operates between a saver who deposits funds in a bank and a borrower who receives a loan from that bank. When a bank serves as a financial intermediary, unlike the situation with a couple on a blind date, the saver and the borrower never meet. In fact, it is not even possible to make direct connections between those who deposit funds in banks and those who borrow from banks, because all funds deposited end up in one big pool, which is then loaned out.

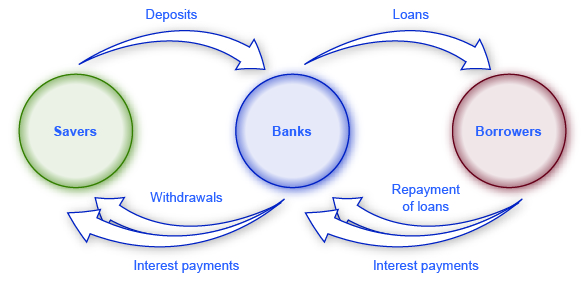

Figure 1 illustrates the position of banks as a financial intermediary, with a pattern of deposits flowing into a bank and loans flowing out, and then repayment of the loans flowing back to the bank, with interest payments for the original savers.

Banks as Financial Intermediaries

Banks are a financial intermediary because they stand between savers and borrowers. Savers place deposits with banks, and then receive interest payments and withdraw money. Borrowers receive loans from banks and repay the loans with interest.

Banks offer a range of accounts to serve different needs. A checking account typically pays little or no interest, but it facilitates transactions by giving you easy access to your money, either by writing a check or by using a debit card (that is, a card which works like a credit card, except that purchases are immediately deducted from your checking account rather than being billed separately through a credit card company). A savings account typically pays some interest rate, but getting the money typically requires you to make a trip to the bank or an automatic teller machine (or you can access the funds electronically). The lines between checking and savings accounts have blurred in the last couple of decades, as many banks offer checking accounts that will pay an interest rate similar to a savings account if you keep a certain minimum amount in the account, or conversely, offer savings accounts that allow you to write at least a few checks per month.

Another way to deposit savings at a bank is to use a certificate of deposit (CD). With a CD, as it is commonly called, you agree to deposit a certain amount of money, often measured in thousands of dollars, in the account for a stated period of time, typically ranging from a few months to several years. In exchange, the bank agrees to pay a higher interest rate than for a regular savings account. While you can withdraw the money before the allotted time, as the advertisements for CDs always warn, there is “a substantial penalty for early withdrawal.”

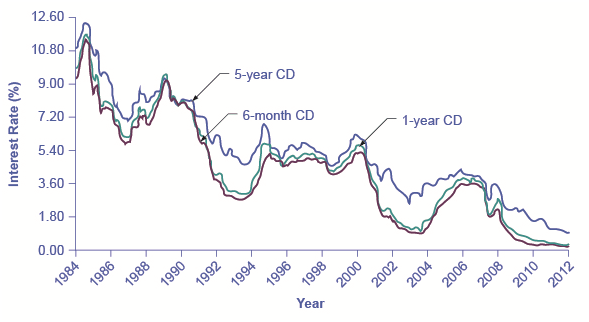

Figure 2 shows the annual rate of interest paid on a six-month, one-year, and five-year CD since 1984, as reported by Bankrate.com. The interest rates paid by savings accounts are typically a little lower than the CD rate, because financial investors need to receive a slightly higher rate of interest as compensation for promising to leave deposits untouched for a period of time in a CD, and thus giving up some liquidity.

Figure 2: Interest Rates on Six-Month, One-Year, and Five-Year Certificates of Deposit

The interest rates on certificates of deposit have fluctuated over time. The high interest rates of the early 1980s are indicative of the relatively high inflation rate in the United States at that time. Interest rates fluctuate with the business cycle, typically increasing during expansions and decreasing during a recession. Note the steep decline in CD rates since 2008, the beginning of the Great Recession.

The great advantages of bank accounts are that financial investors have very easy access to their money. Also, money in bank accounts is extremely safe. In part, this safety arises because a bank account offers more security than keeping a few thousand dollars in the toe of a sock in your underwear drawer. In addition, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) protects the savings of the average person. Every bank is required by law to pay a fee to the FDIC, based on the size of its deposits. If a bank happens to go bankrupt and is unable to repay depositors, the FDIC guarantees that all customers will receive their deposits back up to $250,000.

The bottom line on bank accounts looks like this: low risk means low rate of return but high liquidity.

Bonds

An investor who buys a bond expects to receive a rate of return. However, bonds vary in the rates of return that they offer, according to the riskiness of the borrower. An interest rate can always be divided up into three components: compensation for delaying consumption, an adjustment for an inflationary rise in the overall level of prices, and a risk premium that takes the borrower’s riskiness into account.

The U.S. government is considered an extremely safe borrower, so when the U.S. government issues Treasury bonds, it can pay a relatively low rate of interest. Firms that appear to be safe borrowers, perhaps because of their sheer size or because they have consistently earned profits over time, will still pay a higher interest rate than the U.S. government. Firms that appear to be riskier borrowers, perhaps because they are still growing or their businesses appear shaky, will pay the highest interest rates when they issue bonds. Bonds that offer high interest rates to compensate for their relatively high chance of default are called high yield bonds or junk bonds. A number of today’s well-known firms issued junk bonds in the 1980s when they were starting to grow, including Turner Broadcasting and Microsoft.

A bond issued by the U.S. government or a large corporation may seem to be relatively low risk: after all, the issuer of the bond has promised to make certain payments over time, and except for rare cases of bankruptcy, these payments will be made. If the issuer of a corporate bond fails to make the payments that it owes to its bondholders, the bondholders can require that the company declare bankruptcy, sell off its assets, and pay them as much as it can. Even in the case of junk bonds, a wise investor can reduce the risk by purchasing bonds from a wide range of different companies since, even if a few firms go broke and do not pay, they are not all likely to go bankrupt.

As we noted before, bonds carry an interest rate risk. For example, imagine you decide to buy a 10-year bond that would pay an annual interest rate of 8%. Soon after you buy the bond, interest rates on bonds rise, so now similar companies are paying an annual rate of 12%. Anyone who buys a bond now can receive annual payments of $120 per year, but since your bond was issued at an interest rate of 8%, you have tied up $1,000 and receive payments of only $80 per year. In the meaningful sense of opportunity cost, you are missing out on the higher payments that you could have received. Furthermore, the amount you should be willing to pay now for future payments can be calculated. To place a present discounted value on a future payment, decide what you would need in the present to equal a certain amount in the future. This calculation will require an interest rate. For example, if the interest rate is 25%, then a payment of $125 a year from now will have a present discounted value of $100—that is, you could take $100 in the present and have $125 in the future.

In financial terms, a bond has several parts. A bond is basically an “I owe you” note that is given to an investor in exchange for capital (money). The bond has a face value. This is the amount the borrower agrees to pay the investor at maturity. The bond has a coupon rate or interest rate, which is usually semi-annual, but can be paid at different times throughout the year. (Bonds used to be paper documents with coupons that were clipped and turned in to the bank to receive interest.) The bond has a maturity date when the borrower will pay back its face value as well as its last interest payment. Combining the bond’s face value, interest rate, and maturity date, and market interest rates, allows a buyer to compute a bond’s present value, which is the most that a buyer would be willing to pay for a given bond. This may or may not be the same as the face value.

The bond yield measures the rate of return a bond is expected to pay over time. Bonds are bought not only when they are issued; they are also bought and sold during their lifetimes. When buying a bond that has been around for a few years, investors should know that the interest rate printed on a bond is often not the same as the bond yield, even on new bonds.

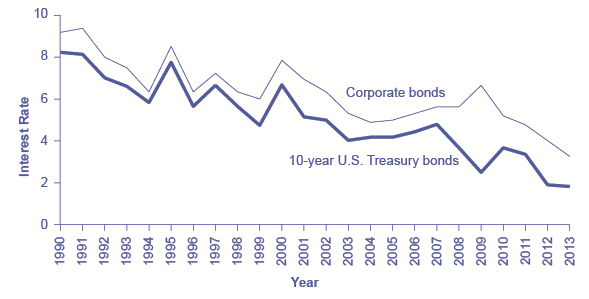

Figure 3 shows bond yield for two kinds of bonds: 10-year Treasury bonds (which are officially called “notes”) and corporate bonds issued by firms that have been given an AAA rating as relatively safe borrowers by Moody’s, an independent firm that publishes such ratings. Even though corporate bonds pay a higher interest rate, because firms are riskier borrowers than the federal government, the rates tend to rise and fall together. Treasury bonds typically pay more than bank accounts, and corporate bonds typically pay a higher interest rate than Treasury bonds.

Interest Rates for Corporate Bonds and Ten-Year U.S. Treasury Bonds

The interest rates for corporate bonds and U.S. Treasury bonds (officially “notes”) rise and fall together, depending on conditions for borrowers and lenders in financial markets for borrowing. The corporate bonds always pay a higher interest rate, to make up for the higher risk they have of defaulting compared with the U.S. government.

The bottom line for bonds: rate of return—low to moderate, depending on the risk of the borrower; risk—low to moderate, depending on whether interest rates in the economy change substantially after the bond is issued; liquidity—moderate, because the bond needs to be sold before the investor regains the cash.

To read more about bond ratings and investing click on the link to the Bonds Online website.

Treasury Notes, Bonds & Bills

When the federal government borrows money for longer than 1 year, it can issue either a Treasury note or a Treasury bond. The T-notes are for those notes that have a maturity date of anywhere from 2-10 years. The T-bills have a maturity date of more than 10 years up to 30 years. Denominations of T-Notes and T-Bonds vary from $1,000 to $5,000. Another type of federal asset is a Treasury bill or a T-Bill. This asset is a short term loan with a maturity of 13, 26, or 52 weeks and a minimum denomination of $10,000. These financial assets are very popular because they are considered the safest of all financial assets. The only collateral the government needs is the faith and credit that people have in the United States government.

Video: What is an IRA?

An Individual Retirement Account (IRA) is a long-term, tax-sheltered time deposit. Anyone can set up an IRA on their own, or as part of an employer-sponsored account. A traditional IRA that allows individuals to direct pretax income, up to specific annual limits, toward investments that can grow tax-deferred (no capital gains or dividend income is taxed). While a Roth IRA is one where contributions are made after taxes so that no taxes are taken out at maturity. Roth IRAs are for those who plan to retire while in a high tax bracket. Tax laws change year to year. Currently, an individual can contribute up to For 2014 and 2015, your total contributions to all of your traditional and Roth IRAs cannot be more than $5500 ($6500 if you're age 50 or older).

Markets for Financial Assets

Capital Markets are markets where money is loaned for more than one year. These loans can be in the form of corporate bonds, government bonds, or long-term certificates of deposit. Money markets make it possible for investors to loan money for less than 1 year.

| Money Market (less than 1 year) | Capital Market (more than 1 year) | |

| Primary Market |

Money Market Mutual Funds Small CDs |

Government Savings Bonds IRAs Money Market Mutual Funds Small CDs |

| Secondary Market |

Jumbo CDs Treasury Bills |

Corporate Bonds International Bonds Jumbo CDs Municipal Bonds Treasury Bonds Treasury Notes |

*If the length of the maturity is important the market is sometimes called a money market or capital market. If the ability to sell the asset to someone other than the original issuer the market may be described as either a primary market or secondary market.

Primary & Secondary Markets

Financial markets are also categorized based on the concept of liquidity, or how the asset can be redeemed. A primary market allows only the original issuer to redeem or purchase the asset when it is sold. Government bonds and IRAs are examples of assets that are non-transferable. Small CDs are also in this category since they can be cashed in early prior to the maturity date.

Secondary markets allow the asset to be sold back to either the original issuer or to another person or group. The most important aspect of this market is the liquidity of the assets. These investments, if strong enough, can be quickly sold to others without a significant penalty for liquidation.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.Self Check Questions

- Define the term "risk."

- What are the four basic investment considerations?

- Define the term "bond." What is a corporate bond? A municipal bond? A savings bond?

- What is the difference between a Treasury note and a Treasury bond?

- What is a Treasury bill?

- Define the term Individual Retirement Account (IRA).

- What is a capital market? A money market?

- What is a primary market? A secondary market?