4.1: Why Get Physical

- Page ID

- 2387

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

National Health Education Standards (NHES)

- 1.12.7 Compare and contrast the benefits of and barriers to practicing a variety of healthy behaviors, such as being physically active every day.

- 6.12.1-6.12.4 Setting and implementing goals and plans to improve health, such as physical activity.

Wellness Guidelines

- Increase frequency of physical activity.

- Decrease sedentary behavior

- Instruction: In a group or think pair share format, have participants discuss the following questions. Acknowledge those who have progressed toward their goal(s) and encourage anyone who wants to change or modify their goal to get 1:1 support.

- Share: Let’s discuss our SMART Goals.

- How is it going with your current SMART goal?

- What are some ways you can improve progress toward your goal? (Grows)

- What are some ways you are doing well with progress towards your goal? (Glows)

GUIDELINE: Increase Frequency of Physical Activity and Decrease Sedentary Behavior

- Share: What guideline do you think is related to today’s lesson? Who has a SMART Goal related to this guideline?

- Instruction: Select one activity.

- Guideline Popcorn: The group lists all 8 guidelines rapidly in popcorn format.

- Guideline Charades: Divide participants into groups and assign each a guideline. Each group has to silently act out the guideline for the rest to guess.

- Two Truths and One Lie:

- Truth 1: Regular physical activity decreases anxiety and stress.

- Truth 2: Regular physical activity increases self-esteem.

- Lie: Regular physical activity makes you more tired during the day.

- Questions to discuss and/or journal:

- What are your favorite physical activities to do?

- Where do you usually do physical activities?

- What are some physical activities you want to try?

- How do you usually feel after participating in a physical activity?

- Why it is important to do physical activity, not only for your body but also for your mind.

- Worksheet

- Slides presentation

- Fitness Personality Quiz Handout

- Academic Fitness Handout

- Do Now

- Physical Activity vs. Sedentary

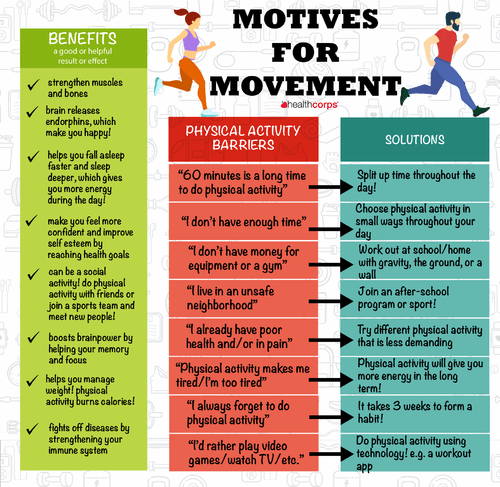

- Motives for Movement

- Academics & Fitness

- Exit Ticket

[As defined by CDC, 2018; HHS, 2012; Merriam-Webster Learner’s Dictionary, n.d.; WHO, n.d.]

- Fitness: Ability to do daily tasks with energy and without getting tired.

- Physical Activity: Any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that require energy expenditure.

- Exercise: Movement of the body that uses energy that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposive.

- Overload: Physical stress placed on the body when the physical activity is greater in amount or intensity than usual.

- Sedentary: Characterized by much sitting and little physical exercise; inactive.

- Evaluate: Determine the significance or worth of something.

- Benefit: A good or helpful result or effect.

- Barrier: A problem that makes something difficult or impossible.

Do Now: Your Fitness Personality

- Instruction:

- Have participants complete the Fitness Personality Quiz Handout.

- Once completed, have everyone shares in think-pair-share groups and/or with the entire group, what their exercise type is.

- Share:

- There are many ways to do physical activity.

- We are all different so we may all prefer a different type of physical activity.

- The activities you like can depend on your personality, so you can use this fitness personality type as a guide for creating your exercise plans and goals.

- What does fitness mean? It is the ability to do daily tasks with energy and without getting tired (HHS, 2008).

- Mostly A's – Competitive: You're always a team player on and off the court. You're game to play any sport that's thrown your way. What are some examples of sports? Soccer, softball, or even a little beach volleyball. Get out there and play hard a couple times a week, but don't forget to give yourself some down time too. Everybody needs a little relaxation to recharge.

- Mostly B's – Social: You may not realize it, but you thrive best when in a group setting. You do the best when going at full-speed, preferably with all your pals on your side. Why not use all this pent-up energy to your benefit and take a class or join a club? What is some example of classes? Martial arts, dance, aerobics, etc. The great thing about fitness classes is you usually go a couple times a week for half an hour or more which is the perfect amount of exercise you should be getting!

- Mostly C's – Solitary: If you're going to exercise, you would rather do it on your own. What are some examples of solo activities? Whether it's swimming, bike riding or even jogging around the park, there are a ton of activities you can do on your own to get fit. Try getting out a couple times a week for at least half an hour.

- Mostly D's – Relaxed: You'd prefer a slower, more relaxed lifestyle, but there are plenty of activities to keep you in shape. What are some examples? Yoga and Pilates are great examples. They combine stretching and breathing techniques to keep you toned. You'll be feeling the burn but you won't be short of breath! Just remember, you want to try to get exercise in a few times a week.

Good to Know: Physical Activity vs. Sedentary

- Share:

- What does physical activity mean? It is any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that require energy expenditure (WHO, n.d.).

- Physical activity is not only important for your physical body (the outside), but it is also important for your mind (the inside).

- Physical activity isn’t just about how your body looks. It changes how you think, how you feel, how long you live, and what you are capable of doing.

- Today, we are going to talk about why it is important to do physical activity for both your body and mind to maintain your overall wellness.

- Fitness is the ability to do daily tasks with energy and without getting tired. (HHS, 2008).

- What does exercise mean? It is planned, a structured, repetitive and intentional movement intended to improve or maintain physical fitness. Exercise is a subcategory of physical activity. (HHS, 2012).

- When are we using energy? All the time. We need to use energy to keep our body functioning (heart beating, lungs breathing, stomach digesting, etc.).

- But are we doing the physical activity all the time? Not necessarily. Your body needs to experience physical stress where the physical activity is greater in amount or intensity than usual. This is also known as overload, and there are three physiological changes that happen when you experience overload (Bogdanis, 2012):

- Heart rate (pulse) increases

- Respiration rate (breathing) increases

- Skin changes color (pink) or has moisture (sweat)

- What does sedentary mean? It is a state that is characterized by sitting frequently and little physical exercise, or inactivity.

- How do you feel after sitting or lying down all day? Responses may include:

- Sore/painful

- Tired

- Weak

- Anxious/sad

- Less focused

- How do you feel after physical activity? Is that different than how you feel after sitting or lying down all day? Which feeling is better? Responses may include:

- Energetic

- Happy

- Clear-headed/focused

- When you have a sedentary lifestyle, you may feel sore, tired, weak, or moody. That’s because our bodies were built to move!

- When you sit all day, your muscles are strained, and over time, they will begin to break down (Vigelsoe et al., 2015).

- Also, your blood cannot circulate as well to deliver important nutrients to different parts of your body such as the brain! In fact, sedentary lifestyle has also been linked with increased risk of several chronic diseases including Type 2 diabetes and heart disease (John Hopkins Health, n.d.).

- It has also been shown that a sedentary lifestyle is linked to more negative emotions, like anxiety, and attention problems (Kantomaa et al., 2008). That’s why it’s so important to get physical!

- Share:

- Optional Instruction:

- Play the following two videos:

- What happens inside your body when you exercise? (British Heart Foundation, 2017): youtu.be/wWGulLAa0O0

- Why Sitting is Bad For You (Ted-Ed, 2015): youtu.be/wUEl8KrMz14

- Play the following two videos:

Real World Relevance: Motives for Movement

- Instruction:

- Brainstorm the benefits of being physically active every day, the barriers to doing so, and how to overcome them.

- Also, identify emotional benefits and barriers.

- As participants share answers to the following questions, record on a board, projector or flip chart paper.

- Share:

- How much physical activity should you get per day?

- Adolescents and children should do physical activity 60 minutes per day and adults should exercise 2 ½ to 5 hours per week (HHS, 2012).

- We are going to evaluate the benefits of physical activity, the recommended amount of time every day, the barriers to it, and how to overcome each barrier. Evaluate means to determine the significance or worth of something.

Image created by HealthCorps staff: Kristina Mariswamy & Rudhi Gokhale

Image created by HealthCorps staff: Kristina Mariswamy & Rudhi GokhaleSources from image:

-U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Retrieved From: https://health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf

-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). The benefits of physical activity. Retrieved From: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/index.htm

-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Physical Activity Facts. Retrieved From: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/facts.htm

- Share: What you like to do probably lies somewhere between the couch and a marathon. Everyone is at different places on the exercise spectrum and need to take baby steps to reach our daily goals.

Hands-On: Academics & Fitness

- Instruction:

- Pass out a relevant article of higher reading level than they are accustomed to seeing and/or boring.

- For example, “Is exercise a viable treatment for depression?” (Blumenthal et al., 2012). An excerpt is included below and also is on the accompanying handout:

- “Depression is a common disorder that is associated with compromised quality of life, increased health care costs, and greater risk for a variety of medical conditions, particularly coronary heart disease. This review examines methods for assessing depression and discusses current treatment approaches. Traditional treatments include psychotherapy and antidepressant medications, but such treatments are not effective for all patients and alternative approaches have recently received increased attention, especially the use of aerobic exercise. This review examines evidence that exercise is effective in improving depressive symptoms among patients with major depression and offers practical suggestions for helping patients initiate and maintain exercise in their daily lives... In summary, exercise appears to be an effective treatment for depression, improving depressive symptoms to a comparable extent as pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Observational studies suggest that active people are less likely to be depressed, and interventional studies suggest that exercise is beneficial in reducing depression. It appears that even modest levels of exercise are associated with improvements in depression, and while most studies to date have focused on aerobic exercise, several studies also have found evidence that resistance training also may be effective. While the optimal “dose” of exercise is unknown, clearly any exercise is better than no exercise. Getting patients to initiate exercise ---and sustain it – is critical” (Blumenthal et al., 2012).

- Instruction:

- Participants will have 1 minute to read. Once the 1 minute is up, they count how many words they read and write down the word where they left off on their worksheet.

- Lead all participants to do a brain break such as 5 jumping jacks, 5 core twists and touch toes for 10 seconds. Immediately ask participants to continue reading where they left off the first time for another 1 minute.

- After that 1 minute, ask them to count the words the second time and write the word where they left off on their worksheet.

- Typically, participants will have read more words the second round. If not, this activity still illustrates the point that exercise helps improve focus.

- Collect the handouts to use with another group, if applicable.

- Share:

- Did you read more words the second round? This is evidence that exercise helps us focus and concentrate.

- What is the article claiming? That exercise can improve symptoms of depression.

- Exit Ticket: 3-2-1

- Instruction:

- Have participants write on their worksheet or share out loud the following question(s).

- What are the 3 benefits of doing physical activity?

- What are the 2 ways of overcoming barriers of physical activity?

- What is 1 type of physical activity you are going to do?

- Have participants write on their worksheet or share out loud the following question(s).

- Bibliography

- A.D.A.M. (2017). Why There's No Excuse Not to Exercise. Retrieved From hsttp://www.ebix.com/blog/theres-no-...-not-exercise/

- Blumenthal, JA., Smith, PJ., & Hoffman, BM. (2012), Is exercise a viable treatment for depression? ACSMs Health Fit J. 16(4): 14-21. Retrieved From: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3674785/

- Bogdanis GC. (2012). Effects of Physical Activity and Inactivity on Muscle Fatigue. Frontiers in Physiology 3:142.

- British Heart Foundation. (2017). What happens inside your body when you exercise? Retrieved From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wWGulLAa0O0

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). The benefits of physical activity. Retrieved From: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity...alth/index.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Physical Activity Facts. Retrieved From: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/p...vity/facts.htm

- Otto, M. W., Church, T. S., Craft, L. L., Greer, T. L., Smits, J. A. J., & Trivedi, M. H. (2007). Exercise for Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 9(4), 287–294.

- John Hopkins Health. (n.d.). Risks of physical inactivity. Retrieved From: http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/cardiovascular_diseases/risks_of_physical_inactivity_85,P00218

- Kantomaa, MT., et al. (2008). Emotional and behavioral problems in relation to physical activity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 40(10):1749-56.

- Mayo Clinic. (2017). Exercise intensity: how to measure it. Retrieved From: http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/fitness/in-depth/exercise-intensity/art-20046887

- Merriam-Webster Learner’s Dictionary. (n.d.). Sedentary. Retrieved From: http://www.learnersdictionary.com/de...tion/sedentary

- Ratini, M. (2017). Exercise: What’s In It For You? WebMD. Retrieved From: http://www.webmd.com/fitness-exercise/ss/slideshow-exercise

- Sharma, A., Madaan, V., & Petty, F. D. (2006). Exercise for Mental Health. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 8(2), 106.Weir, K. (2011). The Exercise Effect. Retrieved From www.apa.org/monitor/2011/12/

- TED-Ed. (2015). Why sitting is bad for you - Murat Dalkilinç. Retrieved From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUEl8KrMz14

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Retrieved From: https://health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). Physical Activity Guidelines for American Midcourse Report: Strategies to Increase Physical Activity Among Youth. Retrieved From: https://health.gov/paguidelines/midc...port-final.pdf• Vigelsoe, A. et al. (2015). Six weeks’ aerobic retraining after two weeks’ immobilization restores leg lean mass and aerobic capacity but does not fully rehabilitate leg strength in young and older men. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine (47)6: 552-560.

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Physical Activity. Retrieved From: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- Resources

- TEDTalk. (2016). Roger Frampton: Why Sitting Down Destroys You. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jOJLx4Du3vU

- Watchwellcast. (2012). Exercise and the brain. Retrieved From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mJW7dYXPZ2o

- Jammin’ Minute (1-minute exercise activity you can do with your class): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6Uyru4fAoc

This lesson was created in partnership with Albert Einstein College of Medicine Department of Epidemiology and Population Health with funding support by the National Institutes of Health NIDDK Grant R01DK097096.