6.2.4: Parabolas and Analytic Geometry

- Page ID

- 14755

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Parabolas and Analytic Geometry

Brandyn is graphing parabolas as a part of his homework assignment. He is familiar with the standard form of a parabola: \(\ y=a x^{2}\), and the longer form: \(\ y-k=a(x-h)^{2}\).

On his third problem, he runs into a snag. He has simplified the equation significantly, and has been trying to get it to fit the standard form, but he keeps coming up with this: \(\ x-4=3(y-3)^{2}\). He can't understand why the y term is the squared one, instead of the x term.

What is going on here?

Parabolas and Analytic Geometry

This is our second lesson on parabolas. In the initial lesson, we explored the parabola using the distance formula, and touched on the use of the focus and directrix. In this lesson, we first examine parabolas from the "analytic geometry" point of view, and then work a few examples with the focus and directrix of a parabola.

Finding the Equation of a Parabola Using Analytic Geometry

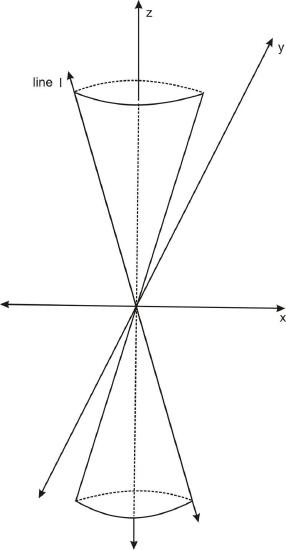

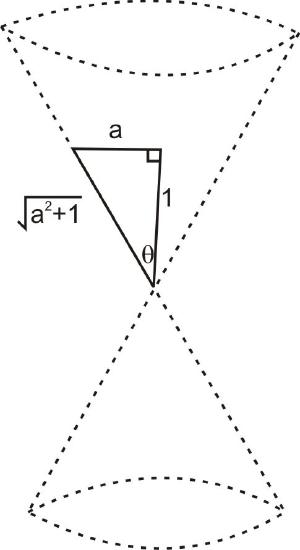

Consider a cone oriented in space as pictured below:

If the cone opens at an angle such that at any point its radius to height ratio is a, then the cone could be defined as the set of points such that the distance from the z−axis is a times the z−coordinate. Or, in other words, the set of points (x, y, z) satisfying:

\(\ \sqrt{(x-0)^{2}+(y-0)^{2}}=a z\)

or

\(\ x^{2}+y^{2}=a^{2} z^{2}\)

This equation works for negative values of x, y, and z, giving the general equation for a two-sided cone.

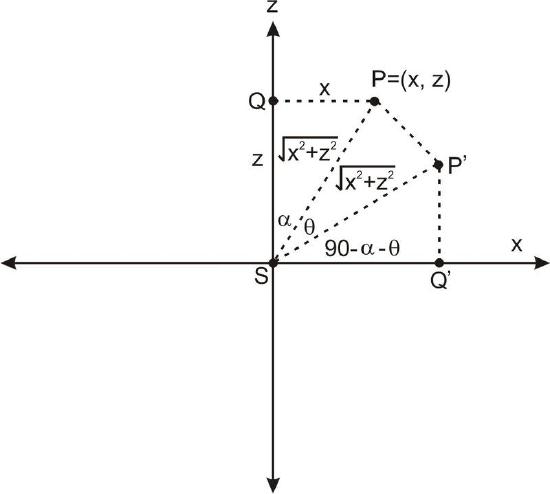

To consider the intersection of this cone with a plane that is parallel to the line marked \(\ l\) marked in the diagram above, it is most convenient to rotate the entire cone about the \(\ y\) axis until the left side of the cone is vertical, then intersect it with a vertical plane perpendicular to the \(\ x\)−axis. Such a rotation leaves the \(\ y\)−variable unchanged. To see what it does to the \(\ x\) and \(\ z\) variables, let’s see what happens to the point \(\ (x,z)\) on the \(\ xz\)−plane when it is rotated by an angle of θ.

In the above diagram, \(\ P(x, z)\) is rotated by an angle of θ to the point \(\ P^{\prime}\). We have marked the side lengths \(\ Q P=x\) and \(\ S Q=z\). By the Pythagorean theorem, \(\ S P=\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}\). We also have \(\ S P^{\prime}=\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}\), since rotation leaves the distance from the origin unchanged. To find the \(\ x\)−coordinates of our rotated point \(\ P^{\prime}\), we can use the fact that

\(\ \cos (90-\alpha-\theta)=\frac{S Q^{\prime}}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}}\). But by properties of cosine we have:

\(\ \cos (90-\alpha-\theta)=\sin (\alpha+\theta)\),

and substituting with the sine addition formula gives us:

\(\ \frac{S Q^{\prime}}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}}=\sin (\alpha) \cos (\theta)+\cos (\alpha) \sin (\theta)\),

which we can use our diagram to change to:

\(\ \frac{S Q^{\prime}}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}}=\frac{x}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}} \cos (\theta)+\frac{z}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}} \sin (\theta)\)

which simplifies to:

\(\ S Q^{\prime}=x \cos (\theta)+z \sin (\theta)\)

To find the \(\ x\)−coordinates of our rotated point \(\ P^{\prime}\), we can use the fact that

\(\ \sin (90-\alpha-\theta)=\frac{P^{\prime} Q^{\prime}}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}}\). But by properties of sine we have:

\(\ \sin (90-\alpha-\theta)=\cos (\alpha+\theta)\)

and substituting with the cosine addition formula gives us:

\(\ \frac{P^{\prime} Q^{\prime}}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}}=\cos (\alpha) \cos (\theta)-\sin (\alpha) \sin (\theta)\),

which we can use our diagram to change to:

\(\ \frac{P^{\prime} Q^{\prime}}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}}=\frac{z}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}} \cos (\theta)-\frac{x}{\sqrt{x^{2}+z^{2}}} \sin (\theta)\)

which simplifies to:

\(\ P^{\prime} Q^{\prime}=z \cos (\theta)-x \sin (\theta)\)

Looking back at the picture, this means that the coordinates of \(\ P^{\prime}\) are \(\ (x \cos (\theta)+z \sin (\theta), z \cos (\theta)-x \sin (\theta))\). In other words, in rotating from \(\ P\) to \(\ P^{\prime}\), the \(\ x\)−coordinate changes to \(\ x \cos (\theta)+z \sin (\theta)\) and the \(\ z\)− coordinate changes to \(\ z \cos (\theta)-x \sin (\theta)\).

If this rotation happens to every point on the cone, we can substitute \(\ x \cos (\theta)+z \sin (\theta)\) for \(\ x\) and \(\ z \cos (\theta)-x \sin (\theta)\) for \(\ z\) into our equation of the cone, resulting in a new equation for the cone after rotating by \(\ \theta\).

\(\ \begin{aligned}

(x \cos (\theta)+z \sin (\theta))^{2}+y^{2} &=a^{2}(z \cos (\theta)-x \sin (\theta))^{2} \\

x^{2} \cos ^{2}(\theta)+2 x z \cos (\theta) \sin (\theta)+z^{2} \sin ^{2}(\theta)+y^{2} &=a^{2}\left(x^{2} \sin ^{2}(\theta)-2 x z \cos (\theta) \sin (\theta)+z^{2} \cos ^{2}(\theta)\right.)\\

x^{2} \cos ^{2}(\theta)+2 x z \cos (\theta) \sin (\theta)+z^{2} \sin ^{2}(\theta)+y^{2} &=a^{2} x^{2} \sin ^{2}(\theta)-2 a^{2} x z \cos (\theta) \sin (\theta)+a^{2} z^{2} \cos(\theta)) \\

x^{2} \cos ^{2}(\theta)+2 x z \cos (\theta) \sin (\theta)+z^{2} \sin ^{2}(\theta)+y^{2} &=a^{2} x^{2} \sin ^{2}(\theta)-2 a^{2} x z \cos (\theta) \sin (\theta)+a^{2} z^{2} \cos(\theta))

\end{aligned}\)

Now in the case of the tilted cone, we want to tilt the cone such that the left side becomes vertical. Since the factor \(\ a\) determines how tilted the cone is, we can see from the triangle below that \(\ \sin (\theta)=\frac{a}{\sqrt{1+a^{2}}}\) and \(\ \cos (\theta)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+a^{2}}}\).

So the equation becomes:

\(\ \begin{aligned}

x^{2} \frac{1}{1+a^{2}}+2 x z \frac{a}{1+a^{2}}+z^{2} \frac{a^{2}}{1+a^{2}}+y^{2} &=a^{2} x^{2} \frac{a^{2}}{1+a^{2}}-2 a^{2} x z \frac{a}{1+a^{2}}+a^{2} z^{2} \frac{1}{1+a^{2}} \\

x^{2}+2 x z a+z^{2} a^{2}+y^{2}\left(1+a^{2}\right) &=a^{4} x^{2}-2 a^{3} x z+a^{2} z^{2} \\

x^{2}+2 x z a+y^{2}\left(1+a^{2}\right) &=a^{4} x^{2}-2 a^{3} x z

\end{aligned}\)

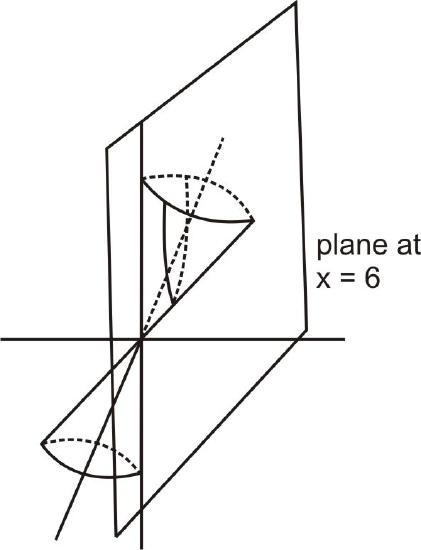

Now that we have tilted our cone, to take a cross section that is parallel to the left side of the cone, we can simply cut it with a vertical plane. The equation of a vertical plane going through \(\ (b, 0,0)\) and perpendicular to the \(\ x\)−axis is \(\ x=b\). Therefore, setting \(\ x\) equal to the constant in the equation above will give us the intersection of the tilted cone and a plane parallel to one side of the cone. \(\ b\). Here is a picture of the rotation and the cross-section, which lies in an \(\ xz\)−plane.

Setting \(\ x\) equal to the constant \(\ b\), we have:

\(\ \begin{aligned}

b^{2}+2 a b z+y^{2}\left(1+a^{2}\right) &=a^{4} b^{2}-2 a^{3} b z \\

z\left(2 a b+2 a^{3} b\right) &=-y^{2}\left(1+a^{2}\right)+a^{4} b^{2}-b^{2} \\

z &=\left(\frac{-1-a^{2}}{2 a b+2 a^{3} b}\right) y^{2}+\left(a^{4} b^{2}-b^{2}\right)

\end{aligned}\)

Although this coefficient and constant term seem complicated, \(\ a\) and \(\ b\) can be chosen so that the coefficient of the \(\ y^{2}\) term can be equal to any number (you will explore this fact in an exercise). The constant term can be ignored since any parabola can be shifted vertically by any amount.

So the general form of a parabola is:

\(\ z=A y^{2}\)

where A is any constant.

Or, using the more standard \(\ x-\) and \(\ y-\text { coordinates }\) the form of a parabola is

\(\ y=a x^{2}\)

As before, this equation can be adapted to produce the shifted and horizontally oriented forms.

Examples

Earlier, you were asked a question about Brandyn, who is unsure why he has a \(\ y^{2}\) term in his standard form equation instead of an \(\ x^{2}\) term.

Solution

Brandyn keeps coming up with a \(\ y^{2}\) term because this is a sideways parabola.

In the proof above, we greatly simplified the formula near the end by substituting A for

\(\ \frac{-1-a^{2}}{2 a b+2 a^{3} b}\)

Solution

Explain why this was permissible by showing that for any \(\ A\) there exist constants \(\ a\) and \(\ b\) such that \(\ A=\frac{-1-a^{2}}{2 a b+2 a^{3} b}\)

Solving for \(\ b\) in terms of \(\ A\) and \(\ a\), we have:

\(\ \begin{aligned}

A\left(2 a b+2 a^{3} b\right) &=-1-a^{2} \\

2 A a b\left(1+a^{2}\right) &=-\left(1+a^{2}\right) \\

2 A a b &=-1 \\

2 A a b &=-1 \\

b &=-\frac{1}{2 A a}

\end{aligned}\)

So we can set \(\ b=2Aa\) and the relationship will hold.

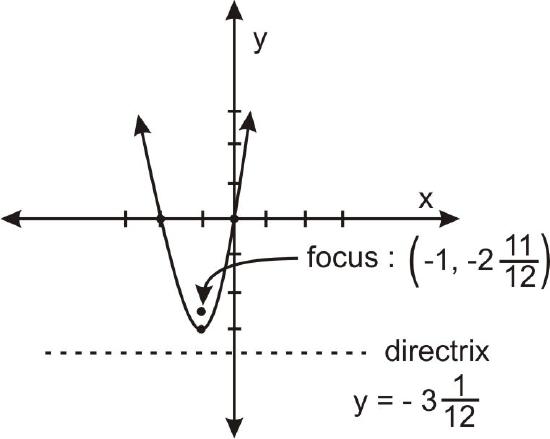

Draw a sketch of the following parabola. Also identify its directrix and focus. \(\ 3 x^{2}+6 x-y=0\)

Solution

Factor and complete the square to get: \(\ 3(x+1)=y+3\). The vertex is at: \(\ (-1,-3)\).

The focus is \(\ \left(-1,-2 \frac{11}{12}\right)\) The directrix is the line \(\ y=-3 \frac{1}{12}\)

Find the equation for a parabola with directrix \(\ y=-2\) and focus \(\ (3,8)\).

Solution

The vertex is vertically midway between the focus and directrix: \(\ \frac{-2+8}{2}=3\), the same horizontally as the focus: \(\ x=3\) and therefore at: \(\ (3,3)\).

Substituting those values into the formula gives:

\(\ y-3=\frac{1}{20}(x-3)^{2}\)

Find the equation for a parabola with directrix \(\ y=3\) and focus \(\ (2, -1)\).

Solution

Using the vertex form of a parabola \(\ (y-k)^{2}=4 a(x-h)\):

Recall that the vertex y-value \(\ k\) is the midpoint of the directrix and the focus on the line perpendicular to the directrix and crossing the focus. Therefore the y-value of the vertex is 1

Recall that the vertex x-value \(\ h\) is the same as the focus, therefore the vertex x-value is 2

Finally, recall that \(\ a\) the distance from the vertex to the focus or from the vertex to the directrix (which are the same): \(\ \therefore a=2\)

Substituting gives: \(\ (y-1)^{2}=8(x-2) \rightarrow y^{2}+1=8 x-16 \rightarrow y^{2}=8 x-17\)

Describe the shape of a parabola as it relates to a cone or double cone.

Solution

The shape of a parabola as it relates to a cone or double cone, is that a parabola represents the revealed shape when a hollow cone is sliced through at an angle equal to the side of the cone. Particularly clear with a double cone is the fact that slicing through at a steeper angle will result in two curves (a hyperbola) and a shallower angle will result in an ellipse.

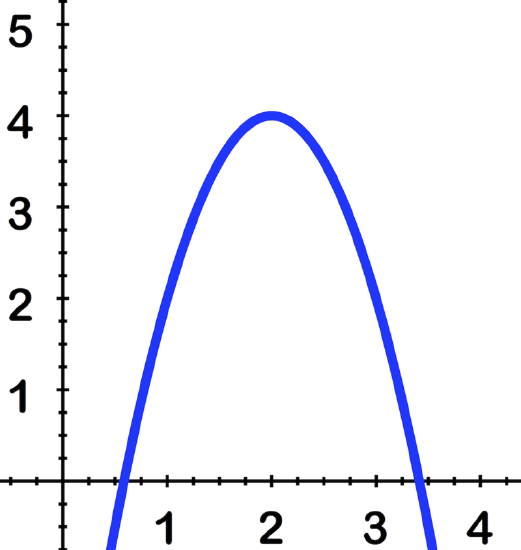

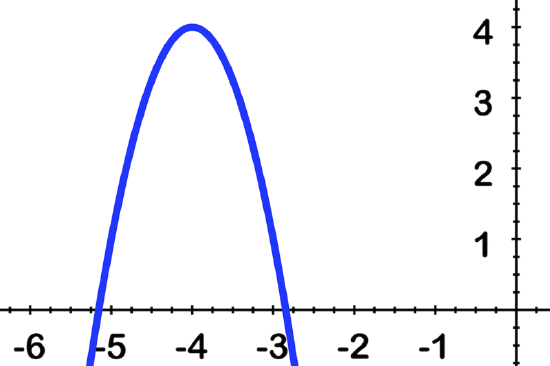

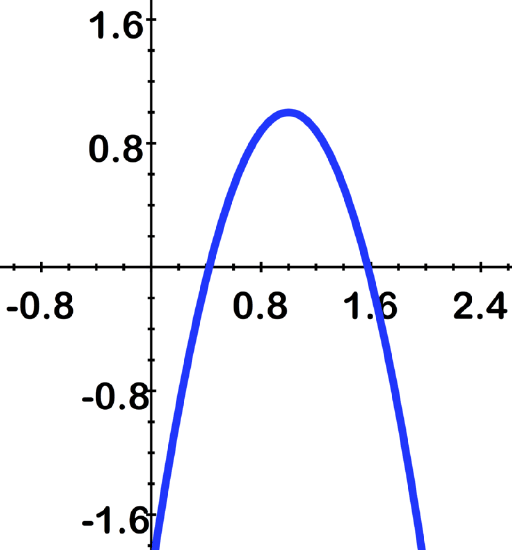

Sketch the following parabola and identify the directrix and focus: \(\ 4 x^{2}-3 x+y=7\).

Solution

\(\ y=a x^{2}+b x+c\)..... Recall the standard form of a parabola

\(\ a=-3|b=6| c=-2\)..... Extract a, b, c

\(\ x=\frac{-6}{2(-3)} \rightarrow x=1\)..... The x-coordinate of the vertex \(\ =\frac{-b}{2 a}\)

\(\ y=(-3)(1)+6(1)-2\)..... Substitute the calculated x-value to solve for \(\ y\)

\(\ y=1\)...... The vertex = (1,1)

\(\ x=1 \pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\)..... Identify the x-intercepts using the Quadratic Formula

Review

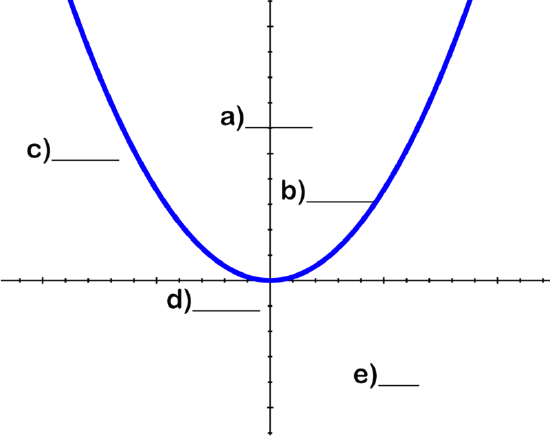

Use the image to identify the parts of the parabola:

- The Focus

- The Vertex

- The Focal Radius

- The Directrix

- The Parabola

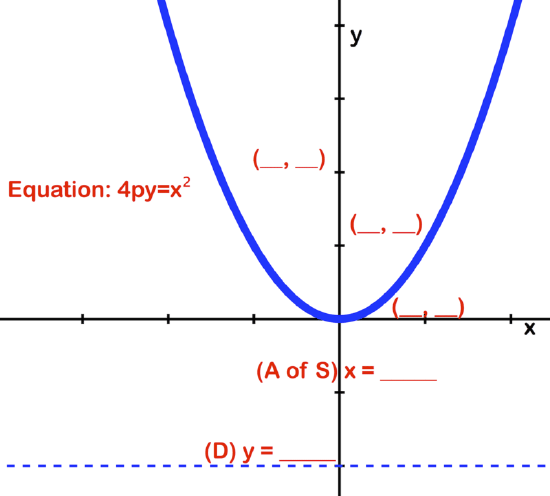

Use the image and given equation of the parabola to identify the following:

- The coordinates of the focus

- The equation of the directrix

- The length of the focal radius

- The equation of the axis of symmetry

- The coordinates of the vertex

- Find the equation for a parabola with directrix: x=2 and focus: (0, −2)

- Find the equation for a parabola with vertex: (5, −2) and directrix: y=−5

- Find the equation for a parabola with focus:(3, 5) and vertex:(3, 1)

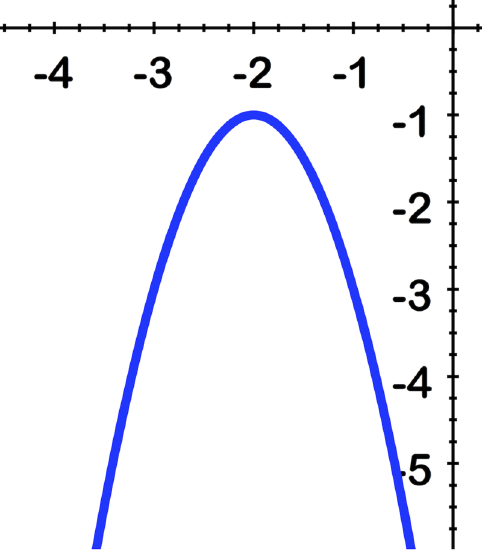

Use the image to identify the vertex, axis of symmetry and equation of the parabola:

Resources

Vocabulary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Analytic Geometry | Analytic geometry is a branch of mathematics concerned with modeling and exploring shapes by using algebraic formulas and a coordinate system. |

| axis of symmetry | The axis of symmetry of a parabola is a vertical line that passes through the vertex of the parabola. The parabola is symmetrical about this line. |

| Conic | Conic sections are those curves that can be created by the intersection of a double cone and a plane. They include circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas. |

| directrix | The directrix of a parabola is the line that the parabola seems to curve away from. All points on a parabola are equidistant from the focus of the parabola and the directrix of the parabola. |

| focus | The focus of a parabola is the point that "anchors" a parabola. Any point on the parabola is exactly the same distance from the focus as from the directrix. |

| Parabola | A parabola is the set of points that are equidistant from a fixed point on the interior of the curve, called the '''focus''', and a line on the exterior, called the '''directrix'''. The directrix is vertical or horizontal, depending on the orientation of the parabola. |