6.3.5: Hyperbolas and Asymptotes

- Page ID

- 14762

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Hyperbolas and Asymptotes

Like other conic sections, hyperbolas can be created by "slicing" a cone and looking at the cross-section. Unlike other conics, hyperbolas actually require 2 cones stacked on top of each other, point to point. The shape is the result of effectively creating a parabola out of both cones at the same time.

So the question is, should hyperbolas really be considered a shape all their own? Or are they just two parabolas graphed at the same time? Could "different" shapes be made from any of the other conic sections if two cones were used at the same time?

Hyperbolas and Asymptotes

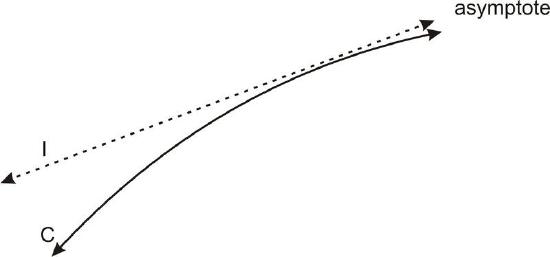

In addition to their focal property, hyperbolas also have another interesting geometric property. Unlike a parabola, a hyperbola becomes infinitesimally close to a certain line as the x− or y−coordinates approach infinity. What we mean by “infinitesimally close?” Here we mean two things: 1) The further you go along the curve, the closer you get to the asymptote, and 2) If you name a distance, no matter how small, eventually the curve will be that close to the asymptote. Or, using the language of limits, as we go further from the vertex of the hyperbola the limit of the distance between the hyperbola and the asymptote is 0.

These lines are called asymptotes.

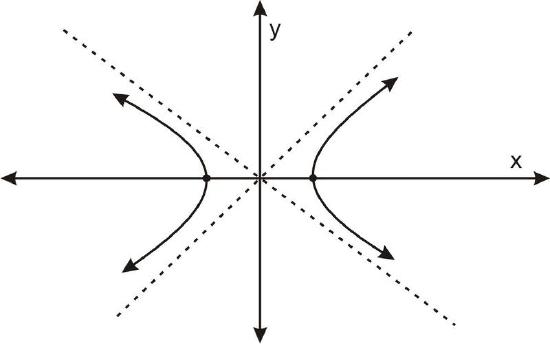

There are two asymptotes, and they cross at the point at which the hyperbola is centered:

For a hyperbola of the form \(\ \frac{x^{2}}{a^{2}}-\frac{y^{2}}{b^{2}}=1\), the asymptotes are the lines:

\(\ y=\frac{b}{a} x\) and \(\ y=-\frac{b}{a} x\).

For a hyperbola of the form \(\ \frac{y^{2}}{a^{2}}-\frac{x^{2}}{b^{2}}=1\) the asymptotes are the lines:

\(\ y=\frac{a}{b} x\) and \(\ y=-\frac{a}{b} x\).

(For a shifted hyperbola, the asymptotes shift accordingly.)

Examples

Earlier, you were asked if hyperbolas should be considered shapes all their own.

Solution

Hyperbolas are considered different shapes, because there are specific behaviors that are unique to hyperbolas. Also, though hyperbolas are the result of dual parabolas, none of the other conics really create unique shapes with dual cones - just double figures - and in any case require multiple "slices".

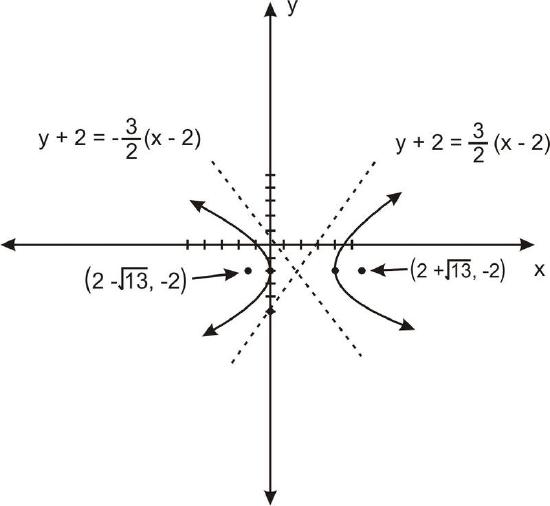

Graph the following hyperbola, drawing its foci and asymptotes and using them to create a better drawing: \(\ 9 x^{2}-36 x-4 y^{2}-16 y-16=0\)

Solution

First, we put the hyperbola into the standard form:

\(\ \begin{aligned}

9\left(x^{2}-4 x\right)-4\left(y^{2}+4 y\right) &=16 \\

9\left(x^{2}-4 x+4\right)-4\left(y^{2}+4 y+4\right) &=36 \\

\frac{(x-2)^{2}}{4}-\frac{(y+2)^{2}}{9} &=1

\end{aligned}\)

So \(\ a=2\), \(\ b=3\) and \(\ c=\sqrt{4+9}=\sqrt{13}\). The hyperbola is horizontally oriented, centered at the point \(\ (2,-2)\), with foci at \(\ (2+\sqrt{13},-2)\) and \(\ (2-\sqrt{13},-2)\). After taking shifting into consideration, the asymptotes are the lines: \(\ y+2=\frac{3}{2}(x-2)\) and \(\ y+2=-\frac{3}{2}(x-2)\). So graphing the vertices and a few points on either side, we see the hyperbola looks something like this:

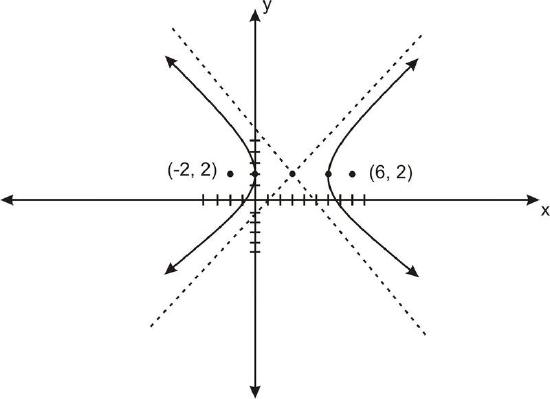

Graph the following hyperbola, drawing its foci and asymptotes and using them to create a better drawing: \(\ 16 x^{2}-96 x-9 y^{2}-36 y-84=0\)

Solution

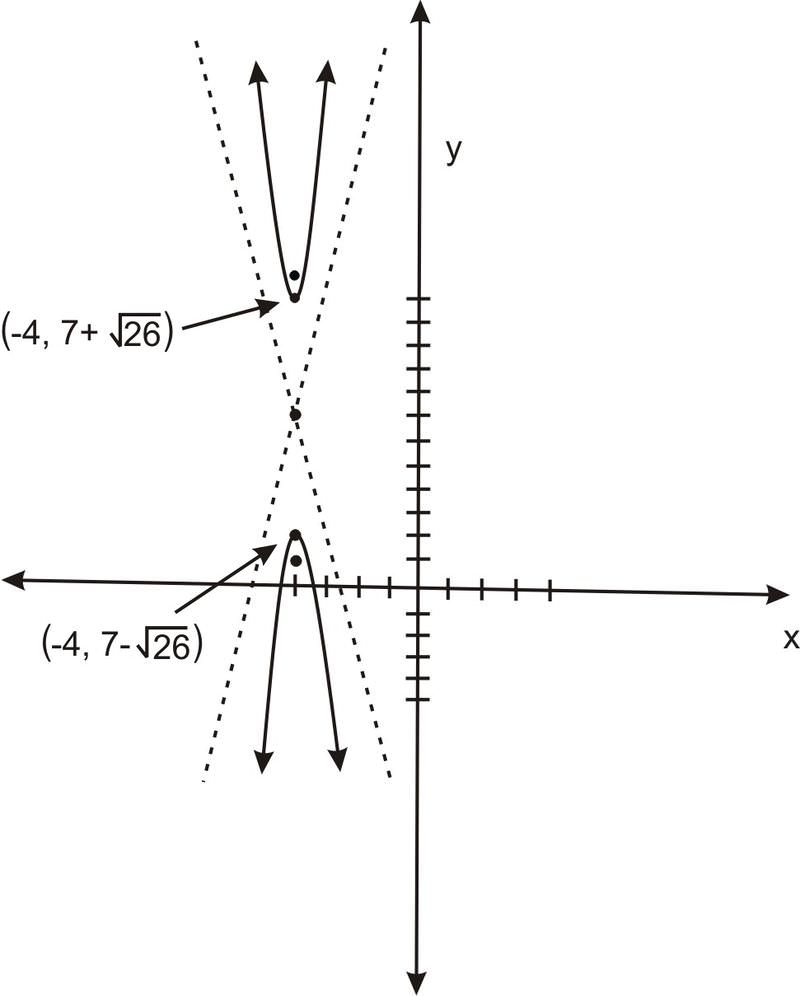

Graph the following hyperbola, drawing its foci and asymptotes, and use them to create a better drawing: \(\ y^{2}-14 y-25 x^{2}-200 x-376=0\).

Solution

Find the equation for a hyperbola with asymptotes of slopes \(\ \frac{5}{12}\) and \(\ -\frac{5}{12}\), and foci at points \(\ (2,11)\) and \(\ (2,1)\).

Solution

\(\ \frac{(y-6)^{2}}{25}-\frac{(x-2)^{2}}{144}=1\)

A hyperbola with perpendicular asymptotes is called perpendicular. What does the equation of a perpendicular hyperbola look like?

Solution

The slopes of perpendicular lines are negative reciprocals of each other. This means that \(\ \frac{a}{b}=\frac{b}{a}\), which, for positive \(\ a\) and \(\ b\) means \(\ a=b\).

Find an equation of the hyperbola with x-intercepts at \(\ x = –7\) and \(\ x = 5\), and foci at \(\ (–6, 0)\) and \(\ (4, 0)\).

Solution

The foci have the same y-coordinates, so this is a left/right hyperbola with the center, foci, and vertices on a line paralleling the x-axis.

Since it is a left/right hyperbola, the y part of the equation will be negative and equation will lead with the \(\ x^{2}\) term (since the leading term is positive by convention and the squared term must have different signs if this is a hyperbola).: The center is midway between the foci, so the center \(\ (h, k)=(-1,0)\). The foci c are 5 units to either side of the center, so \(\ c=5 \rightarrow c^{2}=25\).

The x-intercepts are 4 units to either side of the center, and the foci are on the x-axis so the intercepts must be the vertices \(\ a\) \(\ a=4 \rightarrow a^{2}=16\).

Use the Pythagorean theorem, \(\ a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}\), to get \(\ b^{2}=25-16=9\).

Substitute the calculated values into the standard form \(\ \frac{(x-h)^{2}}{a}-\frac{(y-k)^{2}}{b}=1\) to get \(\ \frac{(x+1)^{2}}{16}-\frac{y^{2}}{9}=1\).

Review

Find the equations of the asymptotes of each hyperbola.

- \(\ \frac{(y+3)^{2}}{4}-(x-2)^{2}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{y^{2}}{16}-(x+3)^{2}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(x+2)^{2}}{4}-\frac{(y+1)^{2}}{9}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(y-4)^{2}}{16}-\frac{(x-4)^{2}}{16}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(x-1)^{2}}{1}-\frac{9(y+4)^{2}}{1}=9\)

- \(\ \frac{(y+2)^{2}}{16}-\frac{(x-2)^{2}}{1}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(x-4)^{2}}{1}-\frac{(y+1)^{2}}{4}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{y^{2}}{16}-\frac{(x+1)^{2}}{4}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(x-3)^{2}}{4}-\frac{(y-4)^{2}}{1}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(x-4)^{2}}{4}-\frac{(y-3)^{2}}{1}=1\)

Graph the hyperbolas, give the equation of the asymptotes, and use the asymptotes to enhance the accuracy of your graph.

- \(\ \frac{(x+4)^{2}}{4}-\frac{(y-1)^{2}}{9}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(y+3)^{2}}{4}-\frac{(x-4)^{2}}{9}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(y+4)^{2}}{16}-\frac{(x-1)^{2}}{4}=1\)

- \(\ (x-2)^{2}-4 y^{2}=16\)

- \(\ \frac{y^{2}}{4}-\frac{(x-1)^{2}}{4}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(x-2)^{2}}{16}-\frac{(y+4)^{2}}{1}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(x+2)^{2}}{9}-\frac{(y+2)^{2}}{16}=1\)

- \(\ \frac{(x+4)^{2}}{9}-\frac{(y-2)^{2}}{4}=1\)

Vocabulary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Asymptotes | An asymptote is a line on the graph of a function representing a value toward which the function may approach, but does not reach (with certain exceptions). |

| Conic | Conic sections are those curves that can be created by the intersection of a double cone and a plane. They include circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas. |

| hyperbola | A hyperbola is a conic section formed when the cutting plane intersects both sides of the cone, resulting in two infinite “U”-shaped curves. |

| Parabola | A parabola is the set of points that are equidistant from a fixed point on the interior of the curve, called the '''focus''', and a line on the exterior, called the '''directrix'''. The directrix is vertical or horizontal, depending on the orientation of the parabola. |

| perpendicular hyperbola | A perpendicular hyperbola has asymptotes that intersect at a 90∘ angle. |

| unbounded | To be unbounded means to be so large that no circle, no matter how large, can enclose the shape. |