3.2: Arguments for the Existence of God from Revelation and Reason

- Page ID

- 2755

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Argument from Revelation

There is an argument to prove that god exists. It is based upon sacred scripture. It is based on the belief that god has revealed god’s existence to humans through the creation or inspiration of the text, which is then thought to be a sacred text. Humans experience the text directly and through that experience many believe that they have contact with the deity. Argument from Revelation consists of:

Sacred Texts-

- Inspired by the deity/intermediary

- Dictated by the deity/intermediary

- Written by the deity/intermediary

Premises/Conclusion:

- The scriptures say that God exists. (Bible, Koran, Vedas, etc.)

- The scriptures are true because they were written by God or by inspired individuals.

- Who inspired these individuals? (God did)

- God is the source and guarantee of truth

- God Exists

This argument or proof is not accepted by rational careful thinkers as it has problems or flaws in it. There are leaks in this "raft". There are different sorts of problems with this argument.

Problems with the Argument

Logical Problem

Fallacy: Classic circular argument

This argument assumes what it is trying to prove and thus is considered to be one of the poorest arguments of all those offered to prove the existence of God. Premise 2 and 4 actually contain the conclusion in it. But the argument is supposed to lead you to the conclusion and not assume the conclusion within the premises. You must accept that the book is from God in order to accept it as being truthful and accurate and then when you accept it as being truthful and accurate you read in it that there is a deity and so conclude that there is a God and that is what you needed to think in order to accept the book as being truthful and accurate in the first place.This circular reasoning would not convince a rational person who was not already a believer in a deity that three was a deity.

Psychological Problem

In addition today there are many people who refuse to believe that the texts are accurate descriptions of events that occurred long ago. People are aware of the psychological phenomenon whereby people who repeat tales are inclined to exaggerate or otherwise distort what actually occurred. Events might have been seen in retrospect as having been directed by a deity or as having some meaning in terms of a plan devised by a deity or as symbolic of the deity.

Textual Problem

Finally, it is now known that what have been considered to be sacred texts were voted upon by the leaders of the religious movements. Certain texts were excluded and others included by deliberate calculation of the practical results desired by those who had the power to declare the texts to be officially inspired or written by the deity.

The use of texts that are considered by some to be sacred are not likely to prove to the non-believer that they are sacred. The use of the texts to prove to a non-believer that there is a sacred source for the inspiration to the authors of the texts is not likely to be convincing when there are alternative explanations for what was created so long ago. Those alternative explanations having to do with human psychology and sociology are being accepted by steadily increasing number of people, including those who claim to be religious. Most simply cannot believe that the reports contained with the scriptures are accurate or true and fewer and fewer can accept the texts as being directed by the deity.

Truth Problem

What sacred text is the most sacred or the most true? A) What version of the sacred text are we to use? and B) the text reports events that cannot be true and cannot be verified and that can be falsified.

Variations in Sacred Texts

If the Argument from Revelation or Scripture is thought to be acceptable by some then there is the need to explain why one scripture is preferable to another and how the other scriptures that contradict the preferred scripture are to be disproved or disallowed.

- God must exist because the scriptures say so. (Bible, Koran, Vedas, Avestas, etc.)

- The scriptures are true because they were written by God or by inspired individuals.

- Who inspired these individuals? (God did)

So which sacred scripture is more sacred or more holy or more true: Bible, New Testament, Koran, Vedas, Avestas?

Variations in Texts of Western Religions

What version is the official version of the "holy book"? Why What versions of these sacred scriptures are to be taken as the official and the truthful versions? In all three traditions of the West: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, there are records to indicate that there were and are variations on the sacred texts. In all three traditions a time came when the community needed to determine what the official version or the Canon would be.

Proofs for the Existence of God: The Ontological Argument

Anselm's Onogicatol Argument

This is the a priori argument -- prior to considering the existence of the physical universe. This is reasoning without bringing in any consideration of the existence of the universe or any part of it. This is an argument considering the idea of god alone.

The argument is considered to be one of the most intriguing ever devised. It took over 400 years for Philosophers to realize what its actual flaws were. As an “a priori” argument, the ontological argument tries to “prove” the existence of God by establishing the necessity of God’s existence through an explanation of the concept of existence or necessary being .

Ontological Argument

Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, first set forth the ontological argument in the eleventh century. This argument is the primary locus for such philosophical problems as whether existence is a property and whether or not the notion of necessary existence is intelligible. It is also the only one of the traditional arguments that clearly leads to the necessary properties of God, such as Omnipotence, Omniscience, etc. Anselm’s argument may be conceived as a “reductiio ad absurdum” argument. In such an argument, one begins with a supposition, which is the contrary to what one is attempting to prove. Coupling the supposition with various existing certain or self-evident assumption will yield a contradiction in the end. This contradiction is what is used to demonstrate that the contrary of the original supposition is true.

There will be several presentations of this argument so that the reader will be able to develop an understanding.

Form 1: Anselm's Argument

Premises/Conclusion:

Anselm - the supreme being - that being greater than which none can be conceived (gcb), the gcb must be conceived of as existing in reality and not just in the mind or else the gcb is not that being greater than which none can be conceived.

- Suppose (S) that the greatest conceivable being (GCB) exists in the mind alone and not in reality(gcb1).

- Then the greatest conceivable being would not be the greatest conceivable being because one could think of a being like (gcb1) but think of the gcb as existing in reality (gcb2) and not just in the mind.

- So, gcb1 would not be the GCB but gcb2 would be.

- Thus to think of the GCB is to think of the gcb2, i.e. a being that exists in reality and not just in the mind.

Form 2: God as Necessary Being

Premises/Conclusion

- God is either a necessary being or a contingent being.

- There is nothing contradictory about god being a necessary being

- So, it is possible that god exists as a necessary being.

- So if it is possible that God is a necessary being then God exists.

- Because God is not a contingent being.

- God must exist as the necessary being.

Anselm begins by defining the most central term in his argument - God. Without asserting that God exists, Anselm asks what is it that we mean when we refer to the idea of "God." When we speak of a God, Anselm implies, we are speaking of the most supreme being. That is, let "god" = "something than which nothing greater can be thought." Anselm's definition of God might sound confusing upon first hearing it, but he is simply restating our intuitive understanding of what is meant by the concept "God." Thus, for the purpose of this argument let "God" = "a being than which nothing greater can be conceived."

Within your understanding, then, you possess the concept of God. As a non-believer, you might argue that you have a concept of unicorn (after all, it is the shared concept that allows us to discuss such a thing) but the concept is simply an idea of a thing. After all, we understand what a unicorn is but we do not believe that they exist. Anselm would agree.

- Two key points have been made thus far: When we speak of God (whether we are asserting God is or God is not), we are contemplating an entity whom can be defined as "a being which nothing greater can be conceived.";

- When we speak of God (either as believer or non-believer), we have an intra-mental understanding of that concept, i.e. the idea is within our understanding.

- It is greater to exist in the mind and in reality, then to exist in the mind alone

Anselm continues by examining the difference between that which exists in the mind and that which exists both in the mind and outside of the mind as well. What is being asked here is: Is it greater to exist in the mind alone or in the mind and in reality (or outside of the mind)? Anselm asks you to consider the painter, e.g. define which is greater: the reality of a painting as it exists in the mind of an artist, or that same painting existing in the mind of that same artist and as a physical piece of art. Anselm contends that the painting, existing both within the mind of the artist and as a real piece of art, is greater than the mere intra-mental conception of the work. Let me offer a real-world example: If someone were to offer you a dollar, but you had to choose between the dollar that exists within their mind or the dollar that exists both in their mind and in reality, which dollar would you choose? Are you sure... At this point, we have a third key point established:

Have you figured out where Anselm is going with this argument?

- If God is that than greater which cannot be conceived (established in #1 above);

- And since it is greater to exist in the mind and in reality than in the mind alone (established in #3 above);

- Then God must exist both in the mind (established in #2 above) and in reality;

- In short, God must be. God is not merely an intra-mental concept but an extra-mental reality as well.

But why? Because if God is truly that than greater which cannot be conceived, it follows that God must exist both in the mind and in reality. If God did not exist in reality as well as our understanding, then we could conceive of a greater being, i.e. a being that does exist extra-mentally and intra-mentally. But, by definition, there can be no greater being. Thus, there must be a corresponding extra-mental reality to our intra-mental conception of God. God's existence outside of our understanding is logically necessary.

Sometimes, Anselm's argument is presented as a Reductio Ad Absurdum (RAA). In an RAA, you reduce to absurdity the antithesis of your view. Since the antithesis is absurd, your view must be correct. Anselm's argument would look something like this:

Premises/Conclusion:

- Either [God exists] or [God does not exist].

- Assume [God does not exist] (the antithesis of Anselm's position)

- If [God does not exist] (but exists only as an intra-mental concept), then that being which nothing greater which can be conceived, is a being which a greater being can be conceived. This is a logical impossibility (remember criterion #3);

- Therefore, [God does not exist] is incorrect;

- Therefore [God exists].

Clarifications:

The argument is not that "If you believe that god exists then god exists". That would be too ridiculous to ask anyone to accept that if you believe that X exists and is real, then X exists and is real.The ontological argument does not ask a person to assume that there is a deity or even a GCB.

It asks anyone to simply think of the deity as the GREATEST CONCEIVABLE BEING and then it indicates that a being that exists in reality (outside of the mind) is greater than one that is just in the mind (imagination). So, the conclusion is that if you think of the GCB you must think that the GCB exists not just in your thinking (mind) but in reality (outside of your mind) as well.

It is greater to think of a being existing outside of the mind as well as in the mind so if you think of the GCB you must think that the GCB exists not just inside of the mind (imagination) but outside of the mind as well (in reality).

Look at it this way: Anselm invites people to think about a certain conception of the deity, i.e., that of the GCB. What Anselm did was to place into the concept itself the idea that the being must exist outside of the mind and in the realm of the real and not just inside the mind in the realm of imagination. So you think of the GCB and what are you doing when you do that? You must think that the GCB exists outside of the mind and in the realm of the real and not just inside the mind in the realm of imagination. Why must you think that? Because it you did not think that, then you would not be thinking of the GCB as defined by Anselm.

It is like this: Think of a triangle. If you do you must think of a three sided figure lying on a plane with three angles adding up to 180 degrees. Why? Because if you are not thinking of a three sided figure lying on a plane with three angles adding up to 180 degrees then you are not thinking of a triangle. So IF you are to think of a triangle you must thnk of a three sided figure lying on a plane with three angles adding up to 180 degrees.

If you are to think of a GCB you must think that the being must exist outside of the mind and in the realm of the real and not just inside the mind in the realm of imagination. Why? Because if you are not thinking that the being must exist outside of the mind and in the realm of the real and not just inside the mind in the realm of imagination then you are not thinking of the GCB. In all of this it is only thinking. Anselm proved what must be thought about the GCB given how the GCB was defined and not whether the GCB actually exists.

Form 3: Modal Version of the Ontological

Argument:

Premises/Conclusion:

- To say that there is possibly a God is to say that there is a possible world in which God exists.

- To say that God necessarily exists is to say that God exists in every possible world.

- God is necessarily perfect (i.e. maximally excellent)

- Since God is necessarily perfect, he is perfect in every possible world.

- If God is perfect in every possible world, he must exist in every possible world, therefore God exists.

- God is also maximally great. To be maximally great is to be perfect in every possible world.

- Therefore: “it is possible that there is a God,” means that there is a possible which contains God, that God is maximally great, and the God exists in every possible world and is consequently necessary.

- God’s existence is at least possible.

- Therefore: as per item seven, God exists.

Form 4: Descartes Cartesian Argument for Existence of God

Argument

Premises/Conclusion

- If there is a God it is a perfect being.

- A perfect being possesses all possible perfections;

- Existence is a perfection;

- Therefore, God necessarily possesses the quality of existence. Simply, God exists.

Problems with the Ontological Argument

The problem with the ontological argument is NOT

- that some people refuse to think of the GCB or

- that some people have a resistance to a belief in a deity

- that some people just refuse to accept the deity

No, the problem with the Argument is that it has FLAWS. It has a LOGICAL MISTAKE in it. What is that error in the argument?

Conclusion of the argument is : Thus, to think of the GCB is to think of the gcb2, i.e. a being that exists in reality and not just in the mind

Immanuel Kant noticed that to think of the GCB is to think of the gcb2, i.e. a being that exists in reality and not just in the mind

But to think of the gcb2 as a being that exists in reality and not just in the mind, does not prove that the gcb2 does actually exist in reality ONLY that a person MUST THINK that the gcb2 does actually exist in reality

But for Kant and many after him , the notion of "Existence" is not a predicate: You cannot include it within the idea of the thing itself. You cannot think anything into existence by including existence as a property of that thing.

Guanillo's Counter - argument to Anselm's Ontological Argument

1. The Most Perfect Island

First: If by "God" we do mean "that than greater which can not be conceived," then the concept is meaningless for us. We can not understand, in any meaningful way, what exactly is meant by such words. The reality behind the term is completely transcendent to the human knower;

Second: Even if we grant that the concept of God as "that than greater which can not be conceived" exists in the understanding, there is no reason to believe that the concept necessitates the extra-mental reality of God. After all, I can imagine the most perfect island, glorious in every detail, but there is nothing about my understanding of the island that forces us to admit the island exists.

2. Existence is not a Predicate

Immanuel Kant (1724 - 1804), offered what many believe to be a damning critique of Anselm's ontological argument.

Let us return to our discussion of unicorns and God. Anselm has argued that there exists a difference between the concept of "unicorn" as it exists intra-mentally and extra-mentally. If we claim that the "unicorn" is, we are somehow adding to the concept. We are endowing the concept with an additional predicate, i.e. the quality that it is. The point of Anselm's argument is that the predicate of existence can be demonstrated for the concept of "God."

Kant does not agree with Anselm's treatment of existence as a predicate. The concept of "unicorn" is not changed in any way if we claim that it is. Nor is the concept damaged if we claim that unicorns are not. According to Kant,"...we do not make the least addition to the thing when we further declare that this thing is." If existence is not a predicate, then Anselm's argument has not demonstrated any meaningful information.

Kant thought that, while the concept of a supreme being was useful, it was only an idea, which in and of itself could not help us in our determining the correctness of the concept. While it was a possibility, he felt that the “a prior" stance of the argument it would be necessary to buttress it with experience.

For Kant what Anselm did was to prove that humans MUST THINK THAT a deity exists in reality and not just in the mind as an idea as the GCB but that does not mean that the GCB actually does exist in reality. The idea of the GCB exists and the idea of the GCB as an actual being does exist but the reality or actuality of the GCB is not established based on the thoughts alone.

Example:

- You go home and look at the top of your dresser. You could use some money and as you look there you imagine seeing ten ten dollar bills.

- You go home and look at the top of your dresser. You could use some money and as you look there you see ten Monopoly dollar bills.

- You go home and look at the top of your dresser. You could use some money and as you look there you see ten real dollar bills.

Which of the three is the greatest or best situation? #3 is. But just thinking about #3 does not actually add any money to your total amount. This is Kant's point.

Thinking about the GCB logically entails "thinking" that the GCB must exist in reality and not just in the imagination. But thinking about the GCB as existing in reality and not just in the imagination does not prove that the GCB actually does exist in reality and not just in the imagination. It is just an idea about what exists.

3. The Greatest Conceivable Evil Being

As an “a priori” argument, the Ontological Argument tries to “prove” the existence of God by establishing the necessity of God’s existence through an explanation of the concept of existence or necessary being. As this criticism of the Ontological Argument shows, the same arguments used to prove an all-powerful god, could be used to prove an all-powerful devil. Since there could not exist two all-powerful beings (one’s power must be subordinate to the other), this is an example of one of the weaknesses in this type of theorizing. Furthermore, the concept of necessary existence, by using Anselm’s second argument, allows us to “define” other things into existence.

The argument could prove the existence of that being more EVIL than which no other can be conceived just as easily as it supposedly proves the existence of the being that is the greatest conceivable being.

Think of a being that is the most evil being that can be conceived. That being must be conceived of as existing in reality and not just in the mind or it wouldn’t be the most evil being which can be conceived for a being that does not exist in reality is not evil at all.

4. Empiricist Critique

Aquinas, 1225-1274, once declared the official philosopher of the Catholic Church, built his objection to the ontological argument on epistemological grounds.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge. It is a branch of philosophy that seeks to answer such questions as: What is knowledge?; What is truth?; How does knowing occur? etc. Aquinas is known as an empiricist. Empiricists claim that knowledge comes from sense experience. Aquinas wrote: "Nothing is in the intellect which was not first in the senses."

Within Thomas' empiricism, we cannot reason or infer the existence of God from a studying of the definition of God. We can know God only indirectly, through our experiencing of God as Cause to that which we experience in the natural world. We cannot assail the heavens with our reason; we can only know God as the Necessary Cause of all that we observe.

Concluding Summary:

What it does prove:

- Anselm proves that if you think of the GCB you must THINK that it exists.

- Descartes proves that if you conceive of an ALL PERFECT being you must CONCEIVE (THINK) of that being as existing.

- Kant points out that even though you must THINK that it exists does not mean that it does exist. Existence is not something we can know from the mere idea itself. It is not known as a predicate of a subject. Independent confirmation through experience is needed.

- The argument does give some support to those who are already believers. It has variations that establish the possibility of the existence of such a being.

- The argument will not convert the non-believer into a believer.

Outcome Assessment

This argument or proof does not establish the actual existence of a supernatural deity. It attempts to define a being into existence and that is not rationally legitimate. While the argument can not be used to convert a non-believer to a believer, the faults in the argument do not prove that there is no god. The Burden of Proof demands that the positive claim that there is a supernatural deity be established by reason and evidence and this argument does not meet that standard. The believer in god can use the argument to establish the mere logical possibility that there is a supernatural deity or at least that it is not irrational to believe in the possibility that there is such a being. The argument does not establish any degree of probability at all.

Suppose (S) that the greatest conceivable being (GCB) exists in the mind alone and not in reality (gcb1). Then the greatest conceivable being would not be the greatest conceivable being because one could think of a being like (gcb1) but think of the gcb as existing in reality (gcb2) and not just in the mind. So, gcb1 would not be the GCB but gcb2 would be. Thus to think of the GCB is to think of the gcb2, i.e. a being that exists in reality and not just in the mind.

Conclusion: The GCB ( Deity) exists

Problem with argument:

- ____Premises are false

- ____Premises are irrelevant

- ____Premises Contain the Conclusion –Circular Reasoning

- _X_ Premises are inadequate to support the conclusion

- ____Alternative arguments exist with equal or greater support

This argument or proof has flaws in it and would not convince a rational person to accept its conclusion. This is not because someone who does not believe in a deity will simply refuse to accept based on emotions or past history but because it is not rationally compelling of acceptance of its conclusion.

Proofs for the Existence of God: The Cosmological Argument

The Cosmological Argument

This argument or proof proceeds from a consideration of the existence and order of the universe. This popular argument for the existence of God is most commonly known as the cosmological argument. Aristotle, much like a natural scientist, believed that we could learn about our world and the very essence of things within our world through observation. As a marine biologist might observe and catalog certain marine life in an attempt to gain insight into that specific thing's existence, so too did Aristotle observe the physical world around him in order to gain insight into his world. The very term cosmological is a reflection of Aristotle's relying upon sense data and observation. The word logos suggests a study of something while the noun cosmos means order or the way things are. Thus, a cosmological argument for the existence of God will study the order of things or examine why things are the way they are in order to demonstrate the existence of God.

The Universe

For Aristotle, the existence of the universe needs an explanation, as it could not have come from nothing. There needs to be a cause for the universe. Nothing comes from nothing so since there is something there must have been some other something that is its cause. Aristotle rules out an infinite progression of causes, so that led to the conclusion that there must be a First Cause. Likewise with Motion, there must have been a First Mover.

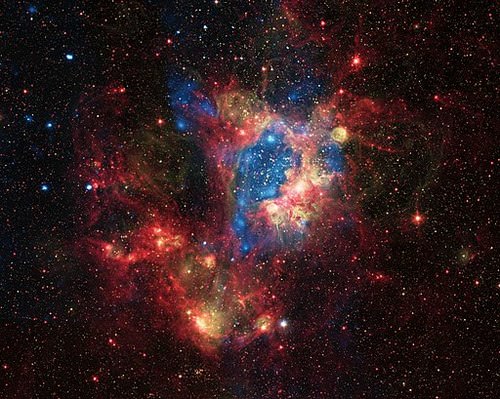

This argument was given support by modern science with the idea of the universe originating in a BIG BANG, a single event from a single point.

The Big Bang Cosmological Theory

St. Thomas Aquinas Cosmological Argument (The Unmoved Mover)

Thomas Aquinas offered five somewhat similar arguments using ideas of the first mover, first cause, the sustainer, the cause of excellence, the source of harmony

Here is a sample of the pattern:

Premises/Conclusion:

- there exists a series of events

- the series of events exists as caused and not as uncaused(necessary)

- there must exist the necessary being that is the cause of all contingent being

- there must exist the necessary being that is the cause of the whole series of beings

The Argument From Motion

Aquinas had Five Proofs for the Existence of God. Let us consider his First argument, the so-called Argument from Motion. Aquinas begins with an observation: Of the things we observe, all things have been placed in motion. No thing has placed itself in motion.

Working from the assumption that if a thing is in motion then it has been caused to be in motion by another thing, Aquinas also notes that an infinite chain of things-in-motion and things-causing-things-to-be-in-motion can not be correct. If an infinite chain or regression existed among things-in-motion and things-causing-things-to-be-in-motion then we could not account for the motion we observe. If we move backwards from the things we observe in motion to their cause, and then to that cause of motion within those things that caused motion, and so on, then we could continuing moving backwards ad infinitum. It would be like trying to count all of the points in a line segment, moving from point B to point A. We would never get to point A. Yet point A must exist as we know there is a line segment. Similarly, if the cause-and-effect chain did not have a starting point then we could not account for the motion we observe around us. Since there is motion, the cause and effect chain (accounting for motion) must have had a starting point. We now have a second point:

The cause and effect relationship among things-being-moved and things-moving must have a starting point. At one point in time, the relationship was set in motion. Thus, there must be a First Cause which set all other things in motion.

What else can we know about the First Cause? The first cause must have been uncaused. If it were caused by another thing, then we have not resolved the problem of the infinite regression. So, in order to account for the motion that we observe, it is necessary to posit a beginning to the cause and effect relationship underlying the observed motion. It is also necessary to claim that the First Cause has not been caused by some other thing. It is not set in motion by another entity.

The First Cause is also the Unmoved Mover. The Unmoved Mover is that being whom set all other entities in motion and is the cause of all other beings. For Aquinas, the Unmoved Mover is that which we call God.

For Aquinas the term motion meant not just motion as with billiard balls moving from point A to point B or a thing literally moving from one place to another. Another sense of the term motion is one that appreciates the Aristotelian sense of moving from a state of potentiality towards a state of actuality. When understood in this way, motion reflects the becoming inherent in the world around us. God as First Cause becomes that entity which designed and set in motion all things in their quest to become. In the least, it is a more poetic understanding of motion.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274) was a theologian, Aristotelian scholar, and philosopher. Called the Doctor Angelicus (the Angelic Doctor,) Aquinas is considered one the greatest Christian philosophers to have ever lived.

Much of St. Thomas's thought is an attempt to understand Christian orthodoxy in terms of Aristotelian philosophy. His five proofs for the existence of God take "as givens" some of Aristotle's assertions concerning being and the principles of being (the study of being and its principles is known as metaphysics within philosophy). Before analyzing further the first of Aquinas' Five Ways, let us examine some of the Aristotelian underpinnings at work within St. Thomas' philosophy.

Aristotle and Aquinas also believed in the importance of the senses and sense data within the knowing process. Aquinas once wrote nothing in the mind that was not first in the senses. Those who place priority upon sense data within the knowing process are known as empiricists. Empirical data is that which can be sensed and typically tested. Unlike Anselm, who was a rationalist, Aquinas will not rely on non-empirical evidence (such as the definition of the term "God" or "perfection") to demonstrate God's existence. St. Thomas will observe the physical world around him and, moving from effect to cause, will try try to explain why things are the way they are. He will assert God as the ultimate Cause of all that is. For Aquinas, the assertion of God as prima causa (first cause) is not so much a blind religious belief but a philosophical and theoretical necessity. God as first cause is at the very heart of St. Thomas' Five Ways and his philosophy in general.

One last notion that is central to St. Thomas' Five Ways is the concept of potentiality and actuality. Aristotle observed that things/substances strive from an incomplete state to a complete state. Things will grow and tend to become as they exist. The more complete a thing is, the better an instance of that thing it is. We have idioms and expressions within our language that reflect this idea. For example, we might say that so-and-so has a lot of potential. We might say that someone is at the peak of their game or that someone is the best at what they do. We might say it just does not get any better than this if we are are having a very enjoyable time. Aristotle alludes to this commonly held intuition when he speaks of organisms moving from a state of potentiality to actuality. When Aquinas speaks of motion within the First Way (the cosmological argument) he is referencing the Aristotelian concepts of potentiality and actuality.

Argument from Contingency

English theologian and philosopher Samuel Clarke set forth a second variation of the Cosmological Argument, which is considered to be a superior version. It is called the “Argument from Contingency”.

Premises/Conclusion:

- Every being that exists is either contingent or necessary.

- Not every being can be contingent.

- Therefore, there exists a necessary being on which the contingent beings depend.

- A necessary being, on which all contingent things depend, is what we mean by “God”.

- Therefore, God exists.

However, there are several weaknesses in the Cosmological Argument, which make it unable to “prove” the existence of God by itself. One is that if it is not possible for a person to conceive of an infinite process of causation, without a beginning, how is it possible for the same individual to conceive of a being that is infinite and without beginning? The idea that causation is not an infinite process is being introduced as a given, without any reasons to show why it could not exist.

Clarke (1675-1729) has offered a version of the Cosmological Argument, which many philosophers consider superior. The “Argument from Contingency” examines how every being must be either necessary or contingent. Since not every being can be contingent, it follows that there must be a necessary being upon which all things depend. This being is God. Even though this method of reasoning may be superior to the traditional Cosmological Argument, it is still not without its weaknesses. One of its weaknesses has been called the “Fallacy of Composition”. The form of the mistake is this: Every member of a collection of dependent beings is accounted for by some explanation. Therefore, the collection of dependent beings is accounted for by one explanation. This argument will fail in trying to reason that there is only one first cause or one necessary cause, i.e. one God .

There are those who maintain that there is no sufficient reason to believe that there exists a self existent being.

Counter Argument:

- If there is a cause for everything then what caused the first cause (God).

- If the first cause can be thought to be uncaused and a necessary being existing forever, then why not consider that the universe itself has always existed and shall always exist and go through a never ending cycle of expansion and contraction and then expansion (big bang) again and again!

- Further, even if a person wanted to accept that there was such a being there is nothing at all in the cosmological argument to indicate that the being would have any of the properties of humans that are projected into the concept of the deity of any particular religion. The first mover or first cause is devoid of any other characteristic.

If there is to be a deity that is the exception from the requirement that all existing things need a cause then the same exception can be made for the sum of all energy that exists, considering that it manifests in different forms.

What the counter argument does is to indicate that the premises of the cosmological argument do not necessarily lead to the conclusion that there is a being that is responsible for the creation of the universe.

So the cosmological argument is neither a valid argument in requiring the truth of its conclusion nor is it a satisfactory argument to prove the existence of any being that would have awareness of the existence of the universe or any event within it.

When a person asks questions such as :

- What is the cause of the the energy or the force or the agent behind the expansion and contraction of the energy?

These questions are considered as "loaded questions" because they load or contain assumptions about what exists or is true that have not yet been established. Why is it that the idea of a "force or agent" is even in the question? Why operate with the assumption that there is such or needs to be such?

We do not know that there is a force "behind" the expansion and contraction. Energy might just expand and contract and there is no force at all other than those generated by the energy-gravitational force, electro-magnetic, strong and weak forces.

In another form this is the "who made God?" question or the "who made the energy?" question. Such an approach to the issue of an explanation for the existence of the universe assumes that there must be an agency. When the idea of an eternal and necessary agency is introduced it was done to provide a form for describing a being that some people wanted as the ultimate explanation - a deity. The point of the counter arguments to the cosmological argument is that the idea of an eternal and necessary agency can as logically be expressed as energy rather than as a single being or entity. If the uncaused cause can be thought of a a single entity then the uncaused cause can be thought of a a single process-energy.

Here is another view of this argument and the rebuttal:

Premises/Conclusion:

- there exists a series of events

- the series of events exists as caused and not as uncaused (necessary)

- there must exist the necessary being that is the cause of all contingent being

- There must exist the necessary being that is the cause of the whole series of beings

Premises/Conclusion

- RULE: Everything that exists must have a cause

- the Universe (multiverse) exists

- the universe (multiverse) must have a cause

- The cause of the universe (multiverse) is GOD

Rebuttal:

- But what is the cause of God?

- God has no cause but is a necessary being. God is an exception to rule.

- If God can be the exception then why not Energy?

Clarke’s “Argument from Contingency”

Premises/Conclusion

- Every being that exists is either contingent or necessary.

- Not every being can be contingent.

- Therefore, there exists a necessary being on which the contingent beings depend.

- A necessary being, on which all contingent things depend, is what we mean by “God”.

- Therefore, God exists.

Rebuttal:

Why not have that a necessary being on which the contingent beings depend is ENERGY itself that changes its form through time?

The Kalam Cosmological Argument

Premises:

- The universe either had a beginning or it did not.

- The universe had a beginning.

- Philosophical arguments for the impossibility of transversing an actual infinite series of events (see above).

- The Big Bang Theory of the Universe postulates a beginning.

- This is the most widely recognized theory of the universe.

- The second law of thermodynamics (entropy).

- The universe is running out of energy.

- If it had an infinite past, it would have run out by now.

- The beginning of the universe was either caused or uncaused.

- The beginning of the universe was caused.

- Contra Hume, every event has a cause.

- God is not an event.

- One might hold that some events, like quantum events, don't need causes.

- If so, then this premise can be replaced with "Everything that begins to exist has a cause."

- The beginning of the universe was caused.

Rebuttal to the Kalam Cosmological Argument

Rebuttal of Cosmological Argument for the Existence of God

Nothing can come from nothing is a fairly well accepted principle since Parmenides. In the West it is taken to be used to support the idea that the universe must have had a creator or a maker or source or origin. However, that is due to the prior storied of a creator being that sets the intellectual environment in which thinking takes place. Now in the East and now in the West there are alternative approaches to the explanation of the universe that we experience.

- Nothing comes from nothing.

- Something does exist.

- Therefore, has never been nothing.

- It is possible that the something that currently exists has always existed.

- The something that exists is always changing.

- Change is a feature of something.

The East has had such notions for millennium. In the West there are now alternative cosmologies to account for the cosmos -- M theory is one of them. A flaw in the cosmological argument is in giving special exclusive status to a deity that would need no creator or origin outside of itself - a necessary being -- without acknowledging that such status could be given to the basic stuff, physis, of the universe, its energy, that can take different forms. What the western thinkers omitted as a possibility was the alternative that there is energy that has always existed and undergoes changes that are time and it can expand and contract and generate multiple dimensions. The Hindus and Buddhists have this sort of idea and so to do the Taoists.

If people need to believe that there was an origination for the universe and that the origination involves an eternal entity then you can have several possibilities including these:

- eternal entity = deity = creator of universe

- eternal entity = energy = continual existence of energy in various forms undergoing continual change = universe

For a explanation of the universe or multiple universes that holds that they have always existed and go through what may be termed cycles see the following as a start from Wikipedia A cyclic model is any of several cosmological models in which the universe follows infinite, self-sustaining cycles.

Outcome Assessment

This argument or proof does not establish the actual existence of a supernatural deity. It attempts to argue for the existence of such a being by making exceptions to rules in the argument and that is not rationally legitimate. While the argument can not be used to convert a non-believer to a believer, the faults in the argument do not prove that there is no god. The Burden of Proof demands that the positive claim that there is a supernatural deity be established by reason and evidence and this argument does not meet that standard. The believer in God can use the argument to establish the mere logical possibility that there is a supernatural deity or at least that it is not irrational to believe in the possibility that there is such a being. The argument does not establish any degree of probability at all when there are alternative explanations for the existence of the known universe.

Premises/Conclusion:

- RULE: Everything that exists must have a cause

- the Universe (multiverse) exists

- the universe (multiverse) must have a cause

- The cause of the universe (multiverse) is God

Rebuttal:

- BUT what is the cause of God?

- God has no cause but is a necessary being. God is an exception to rule.

- The Deity exists.

Problem with argument:

- ____Premises are false

- ____Premises are irrelevant

- ____Premises Contain the Conclusion –Circular Reasoning

- ____Premises are inadequate to support the conclusion

- _X_ Alternative arguments exist with equal or greater support

This argument or proof has flaws in it and would not convince a rational person to accept its conclusion. This is not because someone who does not believe in a deity will simply refuse to accept this proof based on emotions or past history but because it is not rationally compelling of acceptance of its conclusion.

Proofs for the Existence of God: The Teleological Argument

The Teleological Argument or proof for the existence of a deity is sometimes called the Design argument. Even if you have never heard of either argument, you are probably familiar with the central idea of the argument, i.e. there exists so much intricate detail, design , and purpose in the world that we must suppose a creator. All of the sophistication and incredible detail we observe in nature could not have occurred by chance.

When looking at the universe people might see more order or disorder as is their predilection and they might see it in varying proportions. When examining the universe and seeing complexity and order there are a variety of explanations for how it may have come about. Some people want an explanation backed by evidence and without violations of reasoning and some do not want such explanations. Some want the easiest explanations with the least amount of thought. Some merely accept the explanations that they have received when growing up.

The term teleological comes from the Greek words telos and logos. Telos means the goal or end or purpose of a thing while logos means the study of the very nature of a thing. The suffix ology or the study of is also from the noun logos. To understand the logos of a thing means to understand the very why and how of that thing's nature - it is more than just a simple studying of a thing. The teleological argument is an attempt to prove the existence of God that begins with the observation of the purposiveness of nature. The teleological argument moves to the conclusion that there must exist a designer. The inference from design to designer is why the teleological argument is also known as the design argument.

The Teleological Argument

The Teleological Argument is the second traditional “a posteriori” argument for the existence of God. Perhaps the most famous variant of this argument is the William Paley’s “Watch” argument. Basically, this argument says that after seeing a watch, with all its intricate parts, which work together in a precise fashion to keep time, one must deduce that this piece of machinery has a creator, since it is far too complex to have simply come into being by some other means, such as evolution.

The basic premise, of all teleological arguments for the existence of God, is that the world exhibits an intelligent purpose based on experience from nature such as its order, unity, coherency, design and complexity. Hence, there must be an intelligent designer to account for the observed intelligent purpose and order that we can observe.

Paley's teleological argument is based on an analogy: Watchmaker is to watch as God is to universe. Just as a watch, with its intelligent design and complex function must have been created by an intelligent maker: a watchmaker, the universe, with all its complexity and greatness, must have been created by an intelligent and powerful creator. Therefore, a watchmaker is to watch as God is to universe.

The skeleton of the argument is as follows:

Premises/Conclusion:

- Human artifacts are products of intelligent design; they have a purpose.

- The universe resembles these human artifacts.

- Therefore: It is probable that the universe is a product of intelligent design, and has a purpose.

- However, the universe is vastly more complex and gigantic than a human artifact is.

- Therefore: There is probably a powerful and vastly intelligent designer who created the universe.

Paley's Teleological Argument For The Existence Of God

Premises/Conclusion

- Human artifacts are products of intelligent design.

- The universe resembles human artifacts.

- Therefore the universe is a product of intelligent design.

- But the universe is complex and gigantic, in comparison to human artifacts.

- Therefore, there probably is a powerful and vastly intelligent designer who created the universe.

Criticism or Rebuttal of Teleological Argument

- How much order is there?

- What other universes exist to compare this one to them?

- No conclusion to only 1 creator!

- No conclusion to a divine creator!

- No conclusion as to a very intelligent creator!

Alternative explanations exist involving natural processes! Possibility: Aliens? Possibility: Universe making contest amongst multiple deities!

David Hume's Counter Argument

- The universe does not exhibit that much order as there are many indications of disorder such as the collision of galaxies, black holes, nova and supernova, cosmic radiation, gamma radiation, meteor impacts, volcanoes, earthquakes

- argument from parts to whole is not valid

- analogy fails because there are no other universes to compare this one to

- the argument does not prove the existence of only one ( 1) such god

- the argument does not prove that the creator is infinite

David Hume, 1711-1776, argued against the Design Argument through an examination of the nature of analogy. Analogy compares two things, and, on the basis of their similarities, allows us to draw conclusions about the objects. The more closely each thing resembles the other, the more accurate the conclusion. Have you ever heard the expression you are comparing apples to oranges? We use the above-mentioned idiom when we want to express the notion that a comparison is not accurate due to that dissimilarity of things under scrutiny. A good analogy will not compare apples to oranges.

Is the universe similar to a created artifact? Are they similar enough to allow for a meaningful analogy. Hume argues that the two are so dissimilar as to disallow analogy. Further, we know so very little about the universe that we can not compare it to any created thing that is within our knowledge. If we want to employ a valid analogy between, say, the building of a house and the building of the universe we must be able to have an understanding of both terms. Since we can not know about the building of the universe a Design Analogy for the existence of God is nothing more than a guess.

David Hume's Objection to Teleological or Design Argument for Existence of God

The Intelligent Design Theory

In recent years a number of scientists have attempted to supply a variation on the teleological argument that is also a counter to the evolutionary theory. It is called Intelligent Design Theory. This theory disputes that the process of natural selection, the force Darwin suggested drove evolution, is enough to explain the complexity of and within living organisms. This theory holds that the complexity requires the work of an intelligent designer. The designer could be something like the Supreme Being or the Deity of the Scriptures or it could be that life resulted as a consequence of a meteorite from elsewhere in the cosmos, possibly involving extraterrestrial intelligence, or as in new age philosophy that the universe is suffused with a mysterious but inanimate life force from which life results.

One of its weaknesses is that the argument for intelligent design is subject to a great many definitions: What is intelligent design? Opponents of this argument will point out that rather than looking to see if an object looks as if it were designed, we should look at it and determine if its origin could have been natural.

The Theory of Intelligent Design with Morgan Freeman

Question: Doesn’t the fact that the universe is so well designed mean that it must have had a Designer?

Well designed compared to what? The universe is terribly complex, vastly interesting, awe-inspiring—but, as far as we can tell, it is the only one. Since we can all imagine a better-designed universe, even though none of us is divine (ask the folks in areas now suffering from floods or from droughts if they couldn’t design a better water distribution system about now, or contemplate your own appendix or your poor pet’s fleas or West-Nile-virus-bearing mosquitoes), it’s a little hard to know if it’s “well designed.”

And, even if it is, wouldn’t a God necessarily be even better designed—so who designed Him, and then who designed that Designer, ad infinitum?

Most people who bring this one up have in mind some variation of a creationist argument in response to Darwin or other evolutionary theorists. The one usually credited with popularizing or developing this version is William Paley, who described it in Natural Theology (1802). Daniel C. Dennett (1995) argues convincingly that Hume anticipated Paley, having Cleanthes, one of his (Hume’s) three fictional characters in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779/modern reprint, Prometheus Books), lay out the argument.

In any case, the real problem is that design and a “Designer” with a purpose are not necessarily connected. The natural forces at work in the universe do change things, and at least in the case of organic matter, those changes are in a particular direction, or directions. But that does not imply purpose or an intentional destination. Organisms with inheritable characteristics that work better in whatever environment they are in are more likely to survive and reproduce—so “Nature,” or evolutionary forces, do design organisms that are increasingly well adapted and thus are often increasingly complex. Given a few million generations over a few billion years, such design forces can create an astonishing variety of interesting products—but that in no way suggests an omnipotent, omniscient, purposeful Creator.

The Complexity or Improbability Counter Argument

The more the complexity of the universe or the improbability of its actual orderings then the less likely it is that it had or has an intelligent designer.

Irreducible Complexity Argument

The case made by the promoters of the intelligent design argument is actually providing evidence against the conclusion that there must be an intelligent designer. The more the complexity of the universe is advocated or presented by the promoters of the intelligent design argument as a supposed indication of intelligence at work, then the more it works against the conclusion that there must be an intelligent designer. Why? Because if there was an intelligent designer there would be no need for all the complexity and waste observed in the physical universe.

Outcome Assessment

This argument or proof does not establish the actual existence of a supernatural deity. It attempts to argue for the existence of such a being by making comparisons that are questionable and using evidence that is also questionable and for which there alternative explanations and that is not rationally legitimate. While the argument can not be used to convert a non-believer to a believer, the faults in the argument do not prove that there is no god. The Burden of Proof demands that the positive claim that there is a supernatural deity be established by reason and evidence and this argument does not meet that standard. The believer in god can use the argument to establish the mere logical possibility that there is a supernatural deity or at least that it is not irrational to believe in the possibility that there is such a being. The argument does not establish any degree of probability at all when there are alternative explanations for the existence of features of the known universe.

Premises/Conclusion:

- Human artifacts are products of intelligent design.

- The universe resembles human artifacts.

- Therefore the universe is a product of intelligent design.

- But the universe is complex and gigantic, in comparison to human artifacts.

- Therefore, there probably is a powerful and vastly intelligent designer who created the universe.

Problem with argument:

- _X__Premises are false or questionable

- ____Premises are irrelevant

- ____Premises Contain the Conclusion –Circular Reasoning

- _X__Premises are inadequate to support the conclusion

- _X__Alternative arguments exist with equal or greater support

This argument or proof has flaws in it and would not convince a rational person to accept its conclusion. This is not because someone who does not believe in a deity will simply refuse to accept based on emotions or past history but because it is not rationally compelling of acceptance of its conclusion.

Philosophical Applications

Writing assignment: Use the text and outside resources to support your answers. Make sure you completely and thoroughly answer each part.

Arguments for the Existence of God: The arguments for the existence of god have weaknesses. Some have more problems than others. Some seem more attractive and some stronger than others.

- What do you think the value of these arguments to be?

- Why do humans care about these arguments or proofs?

- Since they all have problems, are they necessary for the believer in god?

- Select any one argument: Ontological, Cosmological, Teleological, Miracles, Experience

- describe it

- describe its weakness or flaw

- point out what its attraction would be

- what use a believer can make of it despite its problem.

Vocabulary Quizlet 3.2