5.17: Animal Evolution

- Page ID

- 12118

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

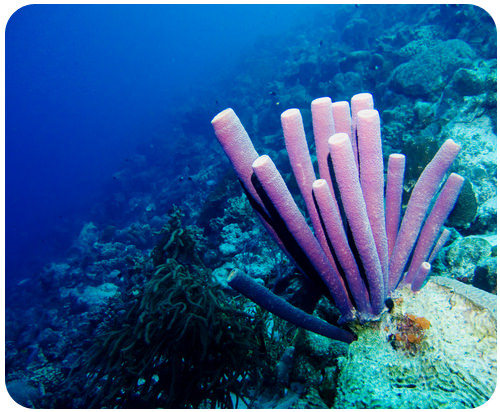

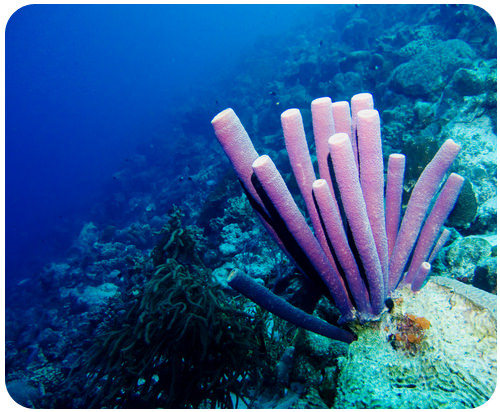

What are these? Are these organisms plants, fungi, protists, or animals?

This colony of tube sponges resembles the pipes of a musical instrument. These sponges are actually animals, although they are the simplest animals on Earth. Sponges are frequently used as shelter for small crabs, shrimps, and other invertebrates.

Major Trends in Animal Evolution

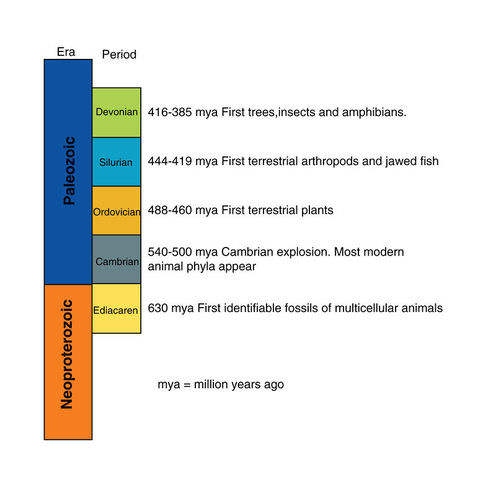

The oldest animal fossils are about 630 million years old. By 500 million years ago, most modern phyla of animals had evolved. Figure below shows when some of the major events in animal evolution took place.

Partial Geologic Time Scale. This portion of the geologic time scale shows major events in animal evolution.

Partial Geologic Time Scale. This portion of the geologic time scale shows major events in animal evolution.Animal Origins

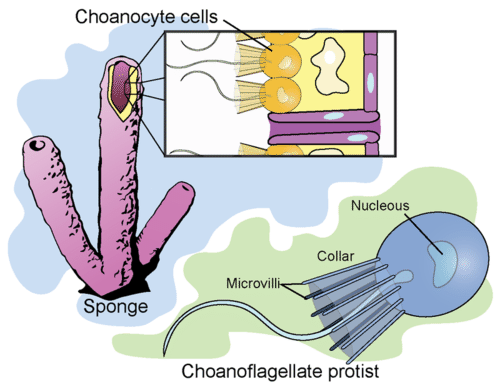

Who were the ancestors of the earliest animals? They may have been marine protists that lived in colonies. Scientists think that cells of some protist colonies became specialized for different jobs. After a while, the specialized cells came to need each other for survival. Thus, the first multicellular animal evolved. Look at the cells in Figure below. One type of sponge cell, the choanocyte, looks a lot like the protist cell. How does this support the hypothesis that animals evolved from protists?

Choanoflagellate Protist and Choanocyte Cells in Sponges. Sponge choanocytes look a lot like choanoflagellate protists.

Choanoflagellate Protist and Choanocyte Cells in Sponges. Sponge choanocytes look a lot like choanoflagellate protists.Evolution of Invertebrates

Many important animal adaptations evolved in invertebrates. Without these adaptations, vertebrates would not have been able to evolve. They include:

- Tissues, organs, and organ systems.

- A symmetrical body.

- A brain and sensory organs.

- A fluid-filled body cavity.

- A complete digestive system.

- A body divided into segments.

Moving from Water to Land

When you think of the first animals to colonize the land, you may think of amphibians. It’s true that ancestors of amphibians were the first vertebrates to move to land. However, the very first animals to go ashore were invertebrates, most likely arthropods.

The move to land required new adaptations. For example, animals needed a way to keep their body from drying out. They also needed a way to support their body on dry land without the buoyancy of water. One way early arthropods solved these problems was by evolving an exoskeleton. This is a non-bony skeleton that forms on the outside of the body. It supports the body and helps retain water. The ability to breath oxygen without gills was another necessary adaptation.

Evolution of Chordates

Another major step in animal evolution was the evolution of a notochord. A notochord is a rigid rod that runs the length of the body. It supports the body and gives it shape (see Figure below). It also provides a place for muscles to anchor, and counterbalances them when they contract. Animals with a notochord are called chordates. They also have a hollow nerve cord that runs along the top of the body. Gill slits and a tail are two other chordate features. Many modern chordates have some of these structures only as embryos.

This tunicate is a primitive, deep-sea chordate. It is using its notochord to support its head, while it waits to snatch up prey in its big mouth.

This tunicate is a primitive, deep-sea chordate. It is using its notochord to support its head, while it waits to snatch up prey in its big mouth.Evolution of Vertebrates

Vertebrates evolved from primitive chordates. This occurred about 550 million years ago. The earliest vertebrates may have been jawless fish, like the hagfish in Figure below. Vertebrates evolved a backbone to replace the notochord after the embryo stage. They also evolved a cranium, or bony skull, to enclose and protect the brain.

Hagfish are very simple vertebrates.

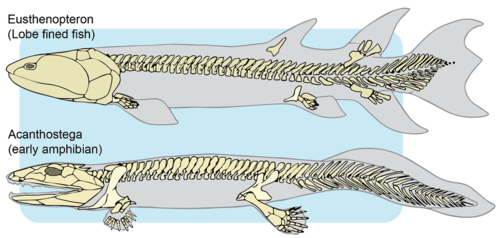

Hagfish are very simple vertebrates.As early vertebrates evolved, they became more complex. Around 365 million years ago, they finally made the transition from water to land. The first vertebrates to live on land were amphibians. They evolved from lobe-finned fish. You can compare a lobe-finned fish and an amphibian in Figure below.

From Lobe-Finned Fish to Early Amphibian. Lobe-finned fish evolved into the earliest amphibians. A lobe-finned fish could breathe air for brief periods of time. It could also use its fins to walk on land for short distances. What similarities do you see between the lobe-finned fish and the amphibian?

From Lobe-Finned Fish to Early Amphibian. Lobe-finned fish evolved into the earliest amphibians. A lobe-finned fish could breathe air for brief periods of time. It could also use its fins to walk on land for short distances. What similarities do you see between the lobe-finned fish and the amphibian?Evolution of Amniotes

Amphibians were the first animals to have true lungs and limbs for life on land. However, they still had to return to water to reproduce. That’s because their eggs lacked a waterproof covering and would dry out on land. The first fully terrestrial vertebrates were amniotes. Amniotes are animals that produce eggs with internal membranes. The membranes let gases but not water pass through. Therefore, in an amniotic egg, an embryo can breathe without drying out. Amniotic eggs were the first eggs that could be laid on land.

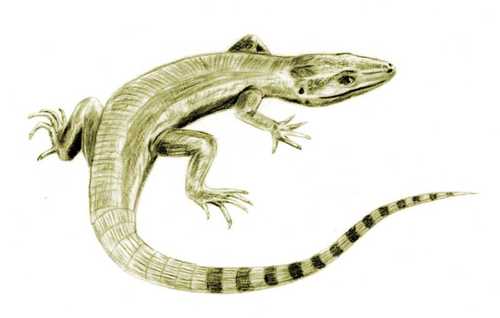

The earliest amniotes evolved about 350 million years ago. They may have looked like the animal in Figure below. Within a few million years, two important amniote groups evolved: synapsids and sauropsids. Synapsids evolved into mammals. The sauropsids gave rise to reptiles, dinosaurs, and birds.

Early Amniote. The earliest amniotes probably looked something like this. They were reptile-like, but not actually reptiles. Reptiles evolved somewhat later.

Early Amniote. The earliest amniotes probably looked something like this. They were reptile-like, but not actually reptiles. Reptiles evolved somewhat later.Further Reading

Summary

- The earliest animals evolved from colonial protists more than 600 million years ago.

- Many important animal adaptations evolved in invertebrates, including tissues and a brain.

- The first animals to live on land were invertebrates.

- Amphibians were the first vertebrates to live on land.

- Amniotes were the first animals that could reproduce on land.

Review

- List three traits that evolved in invertebrate animals.

- Assume that a new species of animal has been discovered. It is an egg-laying animal that lives and reproduces on land. Explain what you know about its eggs without ever seeing them.

- Relate similarities between choanoflagellates and choanocytes to animal origins.

- What was important about the evolution of an exoskeleton?

| Image | Reference | Attributions |

|

[Figure 1] | Credit: User:ArthurWeasley/Wikimedia Commons Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Archaeothyris_BW.jpg License: Public Domain |

|

[Figure 2] | Credit: CK-12 Foundation Source: CK-12 Foundation License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |

|

[Figure 3] | Credit: Mariana Ruiz Villarreal (LadyofHats) for CK-12 Foundation Source: CK-12 Foundation License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |

|

[Figure 4] | Credit: Chika Watanabe Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/chikawatanabe/61157859/ License: CC BY 2.0 |

|

[Figure 5] | Credit: Courtesy of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pacific_hagfish_Myxine.jpg License: Public Domain |

|

[Figure 6] | Credit: Mariana Ruiz Villarreal (LadyofHats) for CK-12 Foundation Source: CK-12 Foundation License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |

|

[Figure 7] | Credit: User:ArthurWeasley/Wikimedia Commons Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Archaeothyris_BW.jpg License: CC BY 2.5 |