13.3: Chemical Weathering

- Page ID

- 5552

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Why is the rock different colors on the surface and in the interior?

This rock is at South Mountain Park in the Phoenix metropolitan area. The climate is often hot and arid. What colors are the rock in this photo? What color is the surface of the rock? What color is the interior? Why do you think there are differences in color between the surface and the interior of this rock? How is chemical weathering altering the landscape?

Chemical Weathering

Chemical weathering is different than mechanical weathering. The minerals in the rock change their chemical makeup. They become a different type of mineral or even a different type of rock. Chemical weathering works through chemical reactions that change the rock.

No Longer Stable

Most minerals form deep within Earth's crust. At these depths, temperatures and pressures are much higher than at the surface. Minerals that were stable deeper in the crust are not stable under surface conditions. That’s why chemical weathering happens. Minerals that formed at higher temperature and pressure change into minerals that are stable at the surface.

Agents of Chemical Weathering

There are many agents of chemical weathering. Remember that water was a main agent of mechanical weathering. Well, water is also an agent of chemical weathering. That makes it a double agent! Carbon dioxide and oxygen are also agents of chemical weathering. Each of these is discussed below.

Water

Water is an amazing molecule. It has a very simple chemical formula, H2O. It is made of just two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom. Water is remarkable in terms of all the things it can do. Lots of things dissolve easily in water. Some types of rock can even completely dissolve in water (Figure below)! Other minerals change by adding water into their structure. Hydrolysis is the name of the chemical reaction between a compound and water.

Weathered rock in Walnut Canyon near Flagstaff, Arizona.

Carbon Dioxide

Carbon dioxide (CO2) combines with water as raindrops fall through the air. This makes a weak acid, called carbonic acid. This happens so often that carbonic acid is a common, weak acid found in nature. This acid works to dissolve rock. It eats away at sculptures and monuments. While this is normal, more acids are made when we add pollutants to the air. Any time we burn any fossil fuel, it adds nitrous oxide to the air. When we burn coal, rich in sulfur, it adds sulfur dioxide to the air. As nitrous oxide and sulfur dioxide react with water, they form nitric acid and sulfuric acid. These are the two main components of acid rain. Acid rain accelerates chemical weathering.

Oxygen

Oxygen strongly reacts with elements at the Earth’s surface. This process is called oxidation. You are probably most familiar with the rust that forms when iron reacts with oxygen. Many minerals are rich in iron. Red rocks are full of iron oxides (Figure below). As iron changes into iron oxide, the iron oxides can also make red color in soils.

The red rocks of Monument Valley are due to the oxidation of iron in the rock.

Plants and Animals

Plants and animals also cause chemical weathering. As plant roots take in nutrients, they remove elements from the minerals. This causes a chemical change in the rock.

Mechanical Weathering and Chemical Weathering

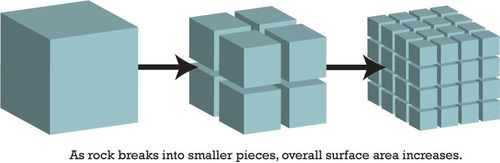

Mechanical weathering increases the rate of chemical weathering. As rock breaks into smaller pieces, the surface area of the pieces increases. With more surfaces exposed, there are more places for chemical weathering to occur (Figure below). Let’s say you wanted to make some hot chocolate on a cold day. It would be hard to get a big chunk of chocolate to dissolve in your milk or hot water. Maybe you could make hot chocolate from some smaller pieces like chocolate chips, but it is much easier to add a powder to your milk. This is because the smaller the pieces are, the more surface area they have. Smaller pieces dissolve more easily.

Mechanical weathering may increase the rate of chemical weathering.

Summary

- Chemical weathering changes the composition of a mineral to break it down.

- Water chemically weathers rock in hydrolysis.

- Carbon dioxide chemically weathers rock by creating acids.

- Oxygen chemically weathers rock by combining with a metal.

Review

- What is hydrolysis?

- How does carbon dioxide lead to chemical weathering?

- How does mechanical weathering increase the effectiveness of chemical weathering processes?

- How do plants contribute to chemical weathering?

Explore More

Use the resource below to answer the questions that follow.

- What is chemical weathering?

- What are the three ways chemical weathering occurs?

- What is oxidation? What does it produced?

- What is carbonation? What does it create?

- What is hydration? What does it do?

- In what type of environment is chemical weathering most likely to occur?