2.3: Amending the Constitution

- Page ID

- 2001

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

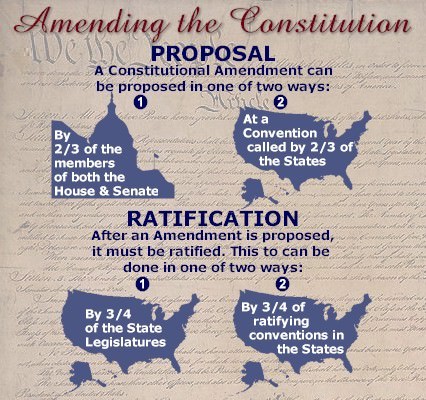

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Article V of the Constitution spells out the processes by which constitutional amendments can be proposed and ratified. As seen below, this is a two-step process. It begins with the proposal of a change to the Constitution and concludes with the ratification process. There are two ways in which Constitutional amendments may be proposed and another two ways by which amendments may be ratified. Each of these will be discussed in this section.

Video: Article V For Dummies: The Amendment Procedure Explained

To Propose Amendments

In the U.S. Congress, both the House of Representatives and the Senate must approve (by a two-thirds supermajority vote) a joint resolution amending the Constitution. Amendments so approved do not require the signature of the president of the United States and are sent directly to the states for ratification.

OR

Two-thirds of the state legislatures must ask Congress to call a national convention to propose amendments. However, to date, this method has never been used.

To Ratify Amendments

Three-fourths of the state legislatures must approve it.

OR

Ratifying conventions in three-fourths of the states must approve it. This method has been used only once -- to ratify the 21st Amendment, which repealed Prohibition.

The Supreme Court has stated that ratification must be within "some reasonable time after the proposal." Beginning with the 18th amendment, it has been customary for Congress to set a definite period for ratification. In the case of the 18th, 20th, 21st, and 22ndamendments, the period set was seven years, but there has been no determination as to just how long a "reasonable time" might extend.

One interesting example of this is the 27th Amendment, which was actually proposed as a part of the Bill of Rights in 1789. This amendment, limiting the power of Congress to give itself a raise without standing for reelection first, was still awaiting ratification in 1992, a record-setting period of 202 years, 6 months and 12 days after it was sent to the states for ratification. It was finally ratified on May 7, 1992.

Of the thousands of proposals that have been made to amend the Constitution, only 33 obtained the necessary two-thirds vote in Congress. Of those 33, only 27 amendments (including the Bill of Rights) have been ratified.

The First Ten (Eleven?) Amendments

When the First Congress convened in 1789, one of its foremost promised orders of business was to consider a series of amendments to the Constitution. These were intended to become part of a "Bill of Rights." Remember that to secure the support of the Anti-Federalists in the fight for ratification, the Federalists promised to add a Bill of Rights to the Constitution after it was in effect.

However, once the First Congress was in session, most of its members were more interested in getting down to the "business of government" than they were in considering amendments to the Constitution. Indeed, if not for James Madison's persistence, repeatedly rising on the House floor to urge the House to consider the promised Constitutional amendments, it is unlikely that the First Congress would have considered them at all.

The reluctance to consider amendments to the Constitution was probably, at least in part, due to the fact that dozens of amendments had been proposed in the various state ratifying conventions. By considering any amendments, members of Congress were probably afraid that nothing else would be accomplished until all of the proposed amendments were considered and voted upon.

Madison, however, studied all of the proposed amendments, discarded the ones he found distasteful, consolidated similar amendments, and trimmed the list down to just ten. By a two-thirds majority in each house, the Congress formally proposed Madison's ten amendments along with two others. They were then sent to the states for ratification. The result was that ten of the proposed amendments were ratified and, thereby, became part of the Constitution. The first ten amendments are often referred to as the Bill of Rights.

Beginning with the 18th Amendment, Congress established a seven-year time limit on the ratification of amendments; however, there was no time limit set on the ratification of amendments proposed before that time. One of the original 12 proposed amendments was not ratified until 1992, a full 203 years after it was proposed by the First Congress! Upon ratification, it became the 27th Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment prohibited any law that increases or decreases the salary of members of Congress from taking effect until the start of the next set of terms of office for Representatives.

The Bill of Rights

| # | Subject | Date submitted for Ratification | Date ratification completed | Ratification time span |

| 1st | Prohibits the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering with the right to peaceably assemble or prohibiting the petitioning for a governmental redress of grievances. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 2nd | Protects the right to keep and bear arms. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 3rd | Prohibits quartering of soldiers in private homes without the owner's consent during peacetime. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 4th | Prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures and sets out requirements for search warrants based on probable cause as determined by a neutral judge or magistrate. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 5th | Sets out rules for indictment by grand jury and eminent domain, protects the right to due process, and prohibits self-incrimination and double jeopardy. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 6th | Protects the right to a fair and speedy public trial by jury, including the rights to be notified of the accusations, to confront the accuser, to obtain witnesses and to retain counsel. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 7th | Provides for the right to trial by jury in certain civil cases, according to common law. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 8th | Prohibits excessive fines and excessive bail, as well as cruel and unusual punishment. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 9th | Protects rights not enumerated in the Constitution. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

| 10th | Reinforces the principle of federalism by stating that the federal government possesses only those powers delegated to it by the states or the people through the Constitution. | September 25, 1789 | December 15, 1791 | 2 years 2 months 20 days |

Categorizing the Amendments

The 27 amendments to the Constitution can roughly be sorted into six broad categories. The first ten amendments are collectively known as the Bill of Rights. For the purposes of this categorization, the 27th Amendment can be included with the first ten because it was proposed by Madison at the same time as the first ten amendments. It is also appropriate to include it with the first ten because it was intended to provide the people protection from unscrupulous elected officials who might abuse their offices for financial gain.

A second set of amendments has specifically addressed the scope of the national government's authority. The 11th Amendment was proposed and ratified in response to a Supreme Court decision regarding sovereign immunity. The 16th Amendment authorized the national government to directly tax the incomes of individuals.

The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were proposed and ratified shortly after the Civil War and were aimed at extending civil rights and liberties to former slaves. Another five amendments, the 12th, 17th, 20th, 22nd, and 25th Amendments have made changes in terms or methods of electing Presidents, Vice-Presidents, and Senators. Four amendments: the 19th, 23rd, 24th, and 26th (the 15thcan also be included in this category) expanded the number of persons eligible to vote in national elections. The 18th Amendment prohibited the consumption of alcohol, and the 21st Amendment canceled the former out.

The Additional Amendments (11-27)

|

# |

Subject |

Date submitted for Ratification |

Date ratification completed |

Ratification time span |

|

11th |

Makes states immune from lawsuits with out-of-state citizens and foreigners not living within the state borders; lays the foundation for sovereign immunity. |

March 4, 1794 |

February 7, 1795 |

11 months 3 days |

|

12th |

Revises presidential election procedures. |

December 9, 1803 |

June 15, 1804 |

6 months 6 days |

|

13th |

Abolishes slavery and involuntary servitude except as punishment for a crime. |

January 31, 1865 |

December 6, 1865 |

10 months 6 days |

|

14th |

Defines citizenship, contains the Privileges or Immunities Clause, the Due Process Clause, the Equal Protection Clause, and deals with post-Civil War issues. |

June 13, 1866 |

July 9, 1868 |

2 years 0 months 26 days |

|

15th |

Prohibits the denial of the right to vote based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude. |

February 26, 1869 |

February 3, 1870 |

11 months 8 days |

|

16th |

Permits Congress to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states or basing it on the United States Census. |

July 12, 1909 |

February 3, 1913 |

3 years 6 months 22 days |

|

17th |

Establishes the direct election of United States Senators by popular vote. |

May 13, 1912 |

April 8, 1913 |

10 months 26 days |

|

18th |

Prohibited the manufacture or sale of alcohol within the United States. (Repealed December 5, 1933) |

December 18, 1917 |

January 16, 1919 |

1 year 0 months 29 days |

|

19th |

Prohibits the denial of the right to vote based on sex. |

June 4, 1919 |

August 18, 1920 |

1 year 2 months 14 days |

|

20th |

Changes the date on which the terms of the President and Vice President (January 20) and Senators and Representatives (January 3) end and begin. |

March 2, 1932 |

January 23, 1933 |

10 months 21 days |

|

21st |

Repeals the 18th Amendment and prohibits the transportation or importation into the United States of alcohol for delivery or use in violation of applicable laws. |

February 20, 1933 |

December 5, 1933 |

9 months 15 days |

|

22nd |

Limits the number of times a person can be elected president. Specifically, a person cannot be elected president more than twice. A person who has served more than two years of a term to which someone else was elected cannot be elected more than once. |

March 24, 1947 |

February 27, 1951 |

3 years 11 months 6 days |

|

23rd |

Grants the District of Columbia electors (the number of electors being equal to the least populous state) in the Electoral College. |

June 16, 1960 |

March 29, 1961 |

9 months 12 days |

|

24th |

Prohibits the revocation of voting rights due to the non-payment of a poll tax. |

September 14, 1962 |

January 23, 1964 |

1 year 4 months 27 days |

|

25th |

Addresses succession to the Presidency and establishes procedures for filling a vacancy in the office of the Vice President and responding to Presidential disabilities. |

July 6, 1965 |

February 10, 1967 |

1 year 7 months 4 days |

|

26th |

Prohibits the denial of the right of US citizens eighteen years of age or older to vote on account of age. |

March 23, 1971 |

July 1, 1971 |

3 months 8 days |

|

27th |

Delays laws affecting Congressional salary from taking effect until after the next election of representatives. |

September 25, 1789 |

May 7, 1992 |

202 years 7 months 12 days |

Why Haven't There Been More Amendments?

Credit for the absence of more amendments can be given to the ingenuity of the Framers and to the flexibility they built into the document. As it has been noted, in many instances the Constitution was left intentionally vague, leaving particular aspects of the document for future generations to interpret.

Constitutional Amendments Proposed and Approved by Congress but NOT Ratified

Six amendments adopted by Congress and sent to the states have not been ratified by the required number of states. Four of these, including one of the twelve Bill of Rights amendments, are still technically open and pending. The other two amendments are closed and no longer pending. One dismissed by terms set within the Congressional Resolution proposing it (†) and the other by terms set within the body of the amendment (‡).

Congressional Apportionment Amendment (pending since September 25, 1789; ratified by 11 states)

Would strictly regulate the size of congressional districts for representation in the House of Representatives.

Title of Nobility Amendment (pending since May 1, 1810; ratified by 12 states)

Would strip citizenship from any United States citizen who accepts a title of nobility from a foreign country.

Corwin Amendment (pending since March 2, 1861; ratified by 3 states)

Would make "domestic institutions" (which in 1861 implicitly meant slavery) of the states impervious to the constitutional amendment procedures enshrined within Article Five of the United States Constitution and immune to abolition or interference even by the most compelling Congressional and popular majorities.

Child Labor Amendment (pending since June 2, 1924; ratified by 28 states)

Would empower the federal government to regulate child labor.

Equal Rights Amendment (ratification period March 22, 1972 to March 22, 1979/June 30, 1982; the amendment failed; ratified by 35 states)

Would prohibit deprivation of equality of rights (discrimination) by the federal or state governments on account of sex.

District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment (ratification period August 22, 1978 to August 22, 1985; the amendment failed; ratified by 16 states)

Would grant the District of Columbia full representation in the United States Congress as if it were a state, repealed the 23rd Amendment and granted the District full representation in the Electoral College system in addition to full participation in the process by which the Constitution is amended.

List of Failed Amendment Proposals NOT Approved by Congress

Approximately 11,539 measures have been proposed to amend the Constitution from 1789 through January 2, 2013. The following amendments, while introduced by a member of Congress, either died in committee or did not receive a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress and were, therefore, they were not sent to the states for ratification.

Nineteenth Century:

More than 1,300 resolutions containing over 1,800 proposals to amend the Constitution had been submitted before Congress during the first century of its adoption. Some prominent proposals included:

Blaine Amendment

Proposed in 1875, it would have banned public funds from going to religious purposes in order to prevent Catholics from taking advantage of such funds. Though it failed to pass, many states adopted such provisions.

Christian Amendment

Proposed first in February 1863, it would have added acknowledgment of the Christian God in the Preamble to the Constitution. Similar amendments were proposed in 1874, 1896 and 1910 with none passing. The last attempt in 1954 did not come to a vote.

The Crittenden Compromise

It was a joint resolution that included six constitutional amendments aimed at protecting slavery. Both the House of Representatives and the Senate rejected it in 1861. Abraham Lincoln was elected on a platform that opposed the expansion of slavery. The South's reaction to the rejection paved the way for the secession of the Confederate states and the American Civil War.

Twentieth-Century:

Anti-Miscegenation Amendment

This was proposed in 1912 by Representative Seaborn Roddenbery, a Democrat from Georgia, to forbid interracial marriage nationwide. Similar amendments were proposed in 1871 by Congressman Andrew King, a Missourian Democrat, and in 1928 by Senator Coleman Blease, a South Carolinian Democrat. None were passed by Congress.

Anti-Polygamy Amendment

This was proposed by Representative Frederick Gillett, a Massachusetts Republican, on January 24, 1914. It was supported by former U.S. Senator from Utah and anti-Mormon activist Frank J. Cannon, and by the National Reform Association.

Bricker Amendment

A proposal from 1951 by Ohio Senator John W. Bricker. It intended to limit the federal government's treaty-making power. Opposed by President Dwight Eisenhower, it failed twice to reach the threshold of two-thirds of voting members necessary for passage--the first time by eight votes, and the second time by a single vote.

Death Penalty Abolition Amendment

A proposal presented in 1990, 1992, 1993, and 1995 by Representative Henry González to prohibit the imposition of capital punishment "by any State, Territory, or other jurisdiction within the United States." The amendment was referred to the House Subcommittee on the Constitution but never made it out of committee.

Flag Desecration Amendment

It was first proposed in 1968 to give Congress the power to make acts such as flag burning illegal. During each term of Congress from 1995 through 2005, the proposed amendment was passed by the House of Representatives but never by the Senate. The closest it came was during voting on June 27, 2006, with 66 in support and 34 opposed. This was one vote short.

Human Life Amendment

First proposed in 1973, it would overturn the Roe v. Wade court ruling. A total of 330 proposals using varying texts have been proposed with almost all dying in committee. The only version that reached a formal floor vote, the Hatch-Eagleton Amendment, was rejected by 18 votes in the Senate on June 28, 1983.

Ludlow Amendment

This was proposed by Representative Louis Ludlow in 1937. This amendment would have heavily reduced America's ability to be involved in a war.

Twenty-first Century:

A Balanced Budget Amendment:

A proposal would force Congress and the President to balance the budget every year (can’t spend more money than collected from revenue). This amendment has been introduced many times.

School Prayer Amendment:

Proposed on April 9, 2003, to establish that "The people retain the right to pray and to recognize their religious beliefs, heritage, and traditions on public property, including schools."

"God" in the Pledge of Allegiance:

Declaring that it is not an establishment of religion for teachers to lead students in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance (with the words "one Nation under God"), proposed on February 27, 2003, by Oklahoma Representative Frank Lucas.

Every Vote Counts Amendment:

Proposed by Congressman Gene Green on September 14, 2004. It would abolish the Electoral College.

Continuity of Government Amendment:

After a Senate hearing in 2004 regarding the need for an amendment to ensure continuity of government in the event that many members of Congress become incapacitated, Senator John Cornyn introduced an amendment to allow Congress to temporarily replace members after at least a quarter of either chamber is incapacitated.

Equal Opportunity to Govern Amendment:

Proposed by Senator Orrin Hatch. It would allow naturalized citizens with at least 20 years of citizenship to become president.

Seventeenth Amendment Repeal:

Proposed in 2004 by Georgia Senator Zell Miller. It would reinstate the appointment of Senators by state legislatures as originally required by Article One, Section Three, Clauses One and Three.

The Federal Marriage Amendment:

Introduced in the United States Congress four times: in 2003, 2004, 2005/2006 and 2008 by multiple members of Congress (with support from then-President George W. Bush). It would define marriage and prohibit same-sex marriage, even at the state level.

Twenty-second Amendment Repeal:

Proposed as early as 1989, various congressmen, including Rep. Barney Frank, Rep. Steny Hoyer, Rep. José Serrano, Rep. Howard Berman, and Sen. Harry Reid, have introduced legislation, but each resolution died before making it out of its respective committee. The current amendment limits the president to two elected terms in office and up to two years succeeding a President in office. The last action was on January 4, 2013, Rep. José Serrano once again introduced H.J. Res. 15 proposing an Amendment to repeal the 22nd Amendment, as he has done every two years since 1997.

Proposed “Anchor Baby” Change to 14th Amendment:

On January 16, 2009, Senator David Vitter of Louisiana proposed an amendment which would deny U.S. citizenship to anyone born in the U.S. unless at least one parent was a U.S. citizen, a permanent resident, or in the armed forces.

Murkowski Amendment:

On February 25, 2009, Senator Lisa Murkowski, because she believed the District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act of 2009 would be unconstitutional if adopted, proposed a Constitutional amendment that would provide a representative to the District of Columbia.

Term Limits for U.S. Senators:

On November 11, 2009, Senator Jim DeMint proposed term limits for the U.S. Congress, where the limit for senators will be two terms for a total of 12 years and for representatives, three terms for a total of six years.

People’s Rights Amendment:

On November 15, 2011, Representative James P. McGovern introduced the People's Rights Amendment, a proposal to limit the Constitution's protections only to the rights of natural persons, and not corporations. This amendment would overturn the United States Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

Saving American Democracy Amendment:

On December 8, 2011, Senator Bernie Sanders filed The Saving American Democracy Amendment. It stated that corporations are not entitled to the same constitutional rights as people. It would also ban corporate campaign donations to candidates. Additionally, it would give Congress and the states broad authority to regulate spending in elections. This amendment would overturn the United States Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

Right to Vote Amendment:

Rep. Jesse Jackson, Jr. backed the Right to Vote Amendment, a proposal to explicitly guarantee the right to vote for all legal U.S. citizens and empower Congress to protect this right; he introduced a resolution for the amendment in the 107th,108th,109th,110th, 111th, and 112th, all of which died in committee. On May 13, 2013, Reps. Mark Pocan and Keith Ellison re-introduced the bill.

Informal Amendments

Unlike formal amendments which change the written word of the U.S. Constitution, informal amendments are changes not affecting the written document but affecting the way the Constitution is interpreted. There are many ways informal amendments can occur but all are affected by two overall political processes:

(1) Societal Change: Sometimes society changes, leading to shifts in how constitutional rights are applied. For example, originally only land-holding white males could vote in federal elections. Due to a burgeoning middle class at the peak of the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s, society became focused on expanding rights for the middle and working classes. This led to the right to vote being extended to more and more people. However, formal recognition of the right of poor whites and black males, and later of women, was only fully secured in the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) and the Nineteenth Amendment (1920).

(2) Judicial Review: In the United States, federal and state courts at all levels, both appellate and trial, are able to review and declare the constitutionality of legislation relevant to any case properly within their jurisdiction. This means that they evaluate whether a law is or is not in agreement with the Constitution and its intent. In American legal language, "judicial review" refers primarily to the adjudication of the constitutionality of statutes, especially by the Supreme Court of the United States.

This is commonly believed to have been established by Chief Justice John Marshall in the case of Marbury vs. Madison, which was argued before the Supreme Court in 1803. A number of other countries whose constitutions provide for such a review of constitutional compatibility of primary legislation have established special constitutional courts with authority to deal with this issue. In these systems, no other courts are competent to question the constitutionality of primary legislation.

Methods of Informal Constitutional Amendment

Legislation:

- Congress can pass laws that spell out some of the Constitution's brief provisions.

- Congress can pass laws defining and interpreting the meaning of constitutional provisions. Congressional legislation is an example of the informal process of amending the U.S. Constitution.

- Two ways in which Congress may informally amend the Constitution is by enacting laws that expand the brief provisions of the Constitution and by enacting laws that further define expressed powers.

- Examples include expanding voting rights, seats in the House, and a minimum wage.

Presidential Action:

- Presidents have used their powers to delineate unclear constitutional provisions. For example, making a difference between Congress's power to declare war and the president's power to wage war.

- Presidents have extended their authority over foreign policy by making informal executive agreements with representatives of foreign governments. This allowed them to avoid the constitutional requirement for the Senate to approve formal treaties. Executive agreements are pacts made by a president with heads of a foreign government.

- Examples include the Vietnam War and NAFTA.

Supreme Court Decisions:

- The nation's courts interpret and apply the Constitution as they see fit, as in Marbury v. Madison, a court case involving the process of informal amendment.

- The Supreme Court has been called "a constitutional convention in continuous session."

- Examples include Brown v. Board of Education and Roe v. Wade.

Traditional/Practical Realities:

- Each branch of government has developed traditions that fall outside the provisions of the Constitution. Prior to Franklin Roosevelt, there was a tradition of the Executive Branch regarding the idea that a president would not serve a third term. However, that "custom" was added to the written Constitution through a formal amendment.

- An example is the Executive Advisory Board, known as the President's Cabinet, and both houses meeting to hear the State of the Union.

Political Parties and Special Interests:

- Political Parties have been a major source of informal amendment by influencing the political process through the selection of candidates, the establishment of national and local party platforms.

- Political parties have shaped government and its processes by holding political conventions, organizing Congress along party lines, and injecting party politics in the process of presidential appointments.

- The fact that government in the United States is in many ways government through a political party is the result of a long history of informal amendments.

- Examples include current primary practices (caucus, superdelegate, etc.) and the two-party system (committees, etc.).

Special interests have been a major source of informal amendment by influencing the political process through exerting influence over elected officials by way of campaign financing and information dissemination.

THE BLAINE AMENDMENT: A FAILED CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT WITH A LASTING LEGACY

In December 1875, Congressman James G. Blaine sought to apply the religion clauses of the First Amendment directly to the states by specifically prohibiting the disbursement of public funds for parochial (church-run) education. In addition, the Senate added a section forbidding the excluding of the Bible from the nation’s public schools. While this proposed Amendment overwhelmingly passed the House of Representatives, it fell four votes short in the Senate, keeping it from being presented to the states and killing its chances of becoming what would have possibly become the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Today, this “failed amendment” has lasting repercussions on national policy and its language has been adopted by a majority of states in this country.

You will examine the Blaine Amendment and analyze its impact in the following ways:

I. Read the overview article on the Blaine Amendment. After reading the article, answer the following questions.

1. According to the author, why does the Blaine Amendment “stand apart” from other failed amendments? (Hint: The author patterns the paper around three specific reasons for the Blaine Amendment’s importance).

2. How has the 14th Amendment been used to address the restrictions intended in the Blaine Amendment even though it was never passed as a Constitutional amendment?

3. How do we see the legacy of the Blaine Amendment today in our present public policy?

4. If the Blaine Amendment were to be proposed again today, would you support it? Explain and defend your answer.

5. What present issues and Court cases have centered around the issues presented in the Blaine Amendment? How do these issues impact your life today?

II. Read the article at The Neutrality Principle and prepare a one-page paper that addresses and answers the following questions. Be sure to support your answers with appropriate evidence and references to the documents that have been provided in this assignment.

1. Briefly describe the issue(s) addressed in this article. Be as specific as possible.

2. What is the overall policy question presented in this article? (Hint: What problem or question is the author presenting to you, the reader?)

3. What is your position on the policy question(s) raised in the article? Briefly (one or two sentences) state your position based on the evidence presented.

4. What evidence in the article supports your position? (Present at least three pieces of evidence)

5. What parts of the article would you consider as contrary to your position? (Be as specific as possible)

A Living Document

Many people today have made the argument that the United States has been gifted with a "living Constitution." This idea has become such a part of the American political psyche that it has almost become a cliché. Junior high students lug home civics textbooks with that title and texts such as this can never avoid at least briefly discussing this topic.

What does this idea mean? Is our Constitution really a “living document?” If so, is this a good idea for the governance of our nation?

It is, as the Founding Fathers would say, self-evident that the Constitution – along with the Bill of Rights, now considered part of the core document – is "alive” in one sense. Our Constitution has existed for well over 227 years, longer than any other such document, yet it continues to be a civic touchstone and the model for constitutional democracies around the world. It is also the standard of governance for new and emerging democracies worldwide.

Describing the Constitution as a “living document” implies that it is a flexible instrument that should adapt to changing times and a changing society. Supporters of this theory of open Constitutional interpretation are described as judicial "activists". For the most part, this is where legal scholars, politicians, and legislators have experienced deep controversy for more than a century. We can see the effects of this debate in everyday life. Whether it be in the State of Texas and its attitude towards conforming with federal mandates, or whether we feel that Obama Care is a fair and constitutional policy or a top-down mandate from an out of control government, or whether it is constitutional or unconstitutional under Article IV of the Constitution for states, such as Texas, to recognize same-sex marriages from other states, all of these are subject to the interpretation of the Constitution on the basis of today’s social and political environment.

Until the 20th century, the "originalist" view of the Constitution was the generally accepted standard of the courts and the legislature alike. There are several interpretations and variations on this philosophy, but it generally means that judges should interpret the Constitution as its framers intended it and would themselves interpret it by using the text itself along with other documents of the time, such as The Federalist Papers.

Prominent 19th-century legal scholar Joseph Story wrote that the Constitution has "a fixed, uniform, permanent construction. It should be ... not dependent upon the passions or parties of particular times, but the same yesterday, today and forever." Judges should not stray from the text's literal meaning. He believed the only proper way to change the text was by formal amendment - what Alexander Hamilton called "some solemn and authoritative act."

Another perspective of Constitutional interpretation and application began to surface in the mid 19th century. This perspective was inspired by the cutting edge science of the time – Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. Legal scholars began to argue that the Constitution should be viewed as a living organism that is capable of adapting over time.

By the start of the 20th century, progressive jurists like Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes were making and defending the argument that the Constitution "must be considered in the light of our whole experience and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago." Holmes said the law was not a matter of absolutes but of the "felt necessities of the time," to be justified by how it contributes "toward reaching a social end."

In other words, while the Constitution was seen as a set of unchanging and fixed laws during the 19th century, 20th-century jurists and scholars began to view the Constitution in a much more flexible and adaptable manner, arguing that its interpretation should be relative to a variety of factors.

This interpretation would depend greatly on three Constitutional Amendments which were neither part of the original Constitution nor the Bill of Rights. These are the “Freedom Amendments” namely the 13th, 14thand 15th Amendments, which were passed by the newly victorious post-Civil War Reconstruction Congress in the late 1860s and early 1870s. In particular, it makes reference to the 14th Amendment and its call for “equal protection under the law.” This has become the centerpiece of both civil rights and civil liberties legislation in addition to the application, or incorporation, of the Bill of Rights to the States on a piecemeal basis over time.

The catch is that judges have been the authorities who have decided how and when the Constitution was evolving. In the 1930s, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes put it bluntly, "We are under a Constitution, but the Constitution is what the judges say it is." Others argued that courts have the right to amend it and that the Supreme Court is a continuing constitutional convention.

If, as the Declaration of Independence argues, the government "derives its powers from the consent of the governed," how can judges who are (in the case of the federal system) unelected by the public and entitled to serve for life, decide when and how to apply and increase those powers?

The popularity of these “originalist” arguments has grown in recent years. Supporters of the originalist interpretation of the Constitution warns that judges may decide to make a "politically correct" ruling, then find some way to justify it through a process of creatively interpreting the law and creating a written precedent that must be followed by judges who hear similar cases. They claim that such judges cannot and should not be allowed to do this forever, or the Constitution will become meaningless. They see these types of jurists as “judicial activists”, and they see themselves as having “judicial restraint” or being “judicial constructivists”. A judicial activist is any judge who uses his powers of judicial review to create policy without the authority of the people or their elected representatives. Judicial restraint is the literal interpretation of the Constitution in deciding such matters without using judicial review to make new law.

Many critics also point out that the only consistent evolutionary movement the Constitution has made is in a socially liberal direction, which places moral, fiscal, and Constitutional conservatives in a much less powerful position. As an example, the power to forbid any "establishment of religion" continues to expand, while the companion guarantee to the "free exercise thereof" shrinks (at least from the more conservative perspective).

It's not that the framers didn’t consider or foresee these changes or the confusion and argument that might be a result. Both James Madison and Thomas Jefferson debated the idea that each generation of Americans should write their own constitution. Jefferson laughed at the "sanctimonious reverence" some would hold for a mere historic document. Madison fretted that without some reverence for continuity, a nation could not have the "requisite stability."

Maybe both were right. Perhaps we really have two constitutions - the written one, which provides a rational continuity, and an unwritten one, which embodies the basic principles behind the document as we now understand them.

For example, look at the "right to privacy." Many Americans make the false assumption that it is one of our basic rights, but the right to privacy is not directly addressed in the Constitution. Instead, it has been created, interpreted and applied over many decades, using the Fourth Amendment's guarantee against "unreasonable searches and seizures," and especially the 14thAmendment's principles of due process and equal protection as well, to a lesser extent, as the 9th Amendment.

Courts have carved out legal zones of privacy around marriage, families, and individuals, overturning laws that required public school attendance, prohibited the use of contraceptives, and more. Last year in Lawrence vs. Texas, a decision that threw out a Texas sodomy law, the court argued that because of the constitutional right to privacy, the government cannot impose a moral point of view on Americans.

Sometimes, the written and unwritten versions conflict. Literally, the Constitution was constructed to preserve the 18th-century status quo regarding slavery, but it was soon read to assert the principle that human rights must be expanded and extended.

We live with such conflict and somehow manage to navigate our way through the uncertainties and challenges that the Constitution will both present us with, as well as correct. As Justice William Brennan wrote, "It is arrogant to pretend that from our vantage we can gauge accurately the intent of the Framers on the application of principle to specific, contemporary questions."

Video: A debate between Supreme Court Justices Antonin Scalia and Stephen Breyer on Original Intent and Living Constitutionalism.

Study/Discussion Questions

For each of the following terms, write a sentence which uses or describes the term in your own words.

|

Amendment |

Bill of Rights |

|

ratify |

1. What is the difference between formal and informal amendments?

2. What does it mean when we describe the Constitution as a "living document?" Provide examples to support your answer.

3. What is the difference between an "originalist" and an "activist" view of the Constitution?

4. What does the Constitution say about the right to privacy? What kind of jurist would support the idea that such a constitutional right exists -- an "originalist" or a "constitutionalist"? Explain your answer.

5. Research examples of each method of informal constitutional amendment process as they were described in this textbook. Describe each method and provide an example from your research.

Sources:

www.clayton.edu/arts-sciences/Constitution-Day/Proposed-Amendments James J. Kilpatrick, ed. (1961). The Constitution of the United States and Amendments Thereto. Virginia Commission on Constitutional Government. p. 49. "Measures Proposed to Amend the Constitution". Statistics & Lists. United States Senate. Ames, Herman Vandenburg (1897). The proposed amendments to the Constitution of the United States during the first century of its history. Government Printing Office. p. 19. Iversen, Joan (1997). The Antipolygamy Controversy in U.S. Women's Movements: 1880-1925: A Debate on the American Home. NY: Routledge. pp. 243–4. "Bricker Amendment". Ohio History Central. Retrieved 13 August 2013. James V. Saturno, “A Balanced Budget Amendment Constitutional Amendment: Procedural Issues and Legislative History,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress No. 98-671, August 5, 1998. 108th Congress, H.J.Res. 46 at Congress.gov "GovTrack: H. J. Res. 103 108th]: Text of Legislation, Introduced in House". Govtrack.us. Retrieved 2008-09-06. "Statement of Chairman Orrin G. Hatch Before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary". Hatch.senate.gov. January 27, 2004. Archived from the original on 2004-04-23. 109th Congress, S.J.Res. 6 at Congress.gov 111th Congress, H.J.Res. 5. Introduced January 6, 2009. 101st Congress, S.J.Res. 36. Sponsored by Harry Reid. January 31, 1989. Govtrack.us, H.J.Res. 15: Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States...

111th Congress, S.J.Res. 6 at Congress.gov

111th Congress, S.J.Res. 11 at Congress.gov

111th Congress, S.J.Res. 21 at Congress.gov

112th Congress, H.J.Res. 88 at Congress.gov

Saving American Democracy Amendment

107th Congress, H.J.Res. 72

108th Congress, H.J.Res. 28

109th Congress, H.J.Res. 28

110th Congress, H.J.Res. 28

111th Congress, H.J.Res. 28

112th Congress, H.J.Res. 28

Press release (May 13, 2013). "Pocan and Ellison Announce Right to Vote Amendment". Congressman Mark Pocan