4.2: The Structure and Functions of the Legislative Branch

- Page ID

- 2031

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

As we previously learned when studying the Constitution, our government is divided into three distinct branches, with each addressed in their own section of the Constitution's first three Articles. Article I created Congress as the legislative, or lawmaking branch of the national government.

Bicameral Nature of Congress

Our Congress was created as a bicameral (or two-house) form of government with the House of Representatives intended to operate on behalf of the people themselves, through direct election and apportionment by population (with larger states receiving proportionally more representatives than smaller states) and the Senate being the body that was designed to represent and defend the interest of the states (through equal representation - two senators for each state and legislative selection of senators rather than direct election).

This bicameral structure was created as a form of compromise between smaller and larger states and was also designed to correct weaknesses that had existed when the United States was under the Articles of Confederation, which was a unicameral (or one-chamber) form of legislature.

When delegates arrived at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, they realized the failure of the unicameral structure of lawmaking under the Articles of Confederation and sought to copy the bicameral structure of the British Parliament but also wanted to strengthen the power of the elected lawmakers by making it the most powerful of the three branches.

The new plan also gave Congress the power to control interstate commerce, which is the exchange of goods and services between citizens that live in different states.

The new plan of bicameral legislation with the House representing the people through direct election and the Senate representing the states through appointment by state legislatures would remain until the 17th Amendment to the Constitution was passed in 1913. This amendment changed the selection of senators from one based on appointment or selection by state legislatures to one in which senators were directly elected by the people. This change occurred because of a series of scandalous elections in the late 1800s and early 1900s that made citizens resent senators who they perceived as being selected because they were friends or business associates of the legislators rather than because they were qualified.

William Jennings Bryan, a congressman from Nebraska, wanted to eliminate or reduce the power that special interest groups had in influencing state legislators as to the selection of senators that would be favorable to big business and special interest groups, so he convinced people to persuade Congress to pass the 17th Amendment, which would allow citizens to directly elect their senators just as they did the representatives.

The Structure of Congress

The Great Compromise of 1787 did more than create a two-chamber Congress. One obvious difference was the number of members. The House has more than four times more members than the Senate. The Senate consists of an equal number of senators per state (two) for a total of 100 (50 states x 2 senators per state = 100 senators). But the number of representatives apportioned to each state changes as the population of the United States changes, as determined by a census (or official count of people), which occurs every ten years. This is because representatives are apportioned on the basis of congressional districts, which represent roughly the same number of people in each. Every state must be given at least one representative (regardless of population) but after that, the number of representatives a state receives is based on its population. Since the Apportionment Act of 1911, also called "Public Law 62-5," there has been a constant number of representatives (435). Every ten years some states (like Texas) may see more representatives allotted to them as their population increases, but for every state that receives a new representative district, another state must lose one.

As of 2019, the most populous state, California, currently has 53 representatives. On the other end of the spectrum, there are seven states with only one representative each (Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming). Texas currently has 36 representatives including Veronica Escobar, Democrat from El Paso. Escobar became the first Latina congresswoman to represent the 16th district in Texas. The total number of voting representatives is fixed by law at 435. In addition, there are six non-voting representatives who have a voice on the floor and a vote in committees, but no vote on the floor. These non-voting members represent Washington D.C. and the other territories of the United States that are not states, including Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In addition, these territories (and the District of Columbia) do not have any representation in the Senate, which only represents the states themselves.

Today, a congressional district consists of approximately 700,000 citizens (except, of course for those seven states whose population does not warrant more than one representative). The natural question, of course, would be "why not just add more representatives as the population of the country grows?" This was the concern of the Congressional members who passed the Apportionment Act in 1911. Their main concern was that there simply wasn't enough physical space to house so many representatives and they were also concerned that Congress would simply become too large to really accomplish anything, so they put a limit on the number of representatives at 435, which remains today.

In order to fairly distribute representatives to the states, a census is taken every ten years (with the last one being in 2010). They count the number of people living in the United States and also look at where these people live. They then readjust the boundaries of the congressional districts (which is usually a task left up to the individual state legislatures after each state is told how many representatives they will be allotted).

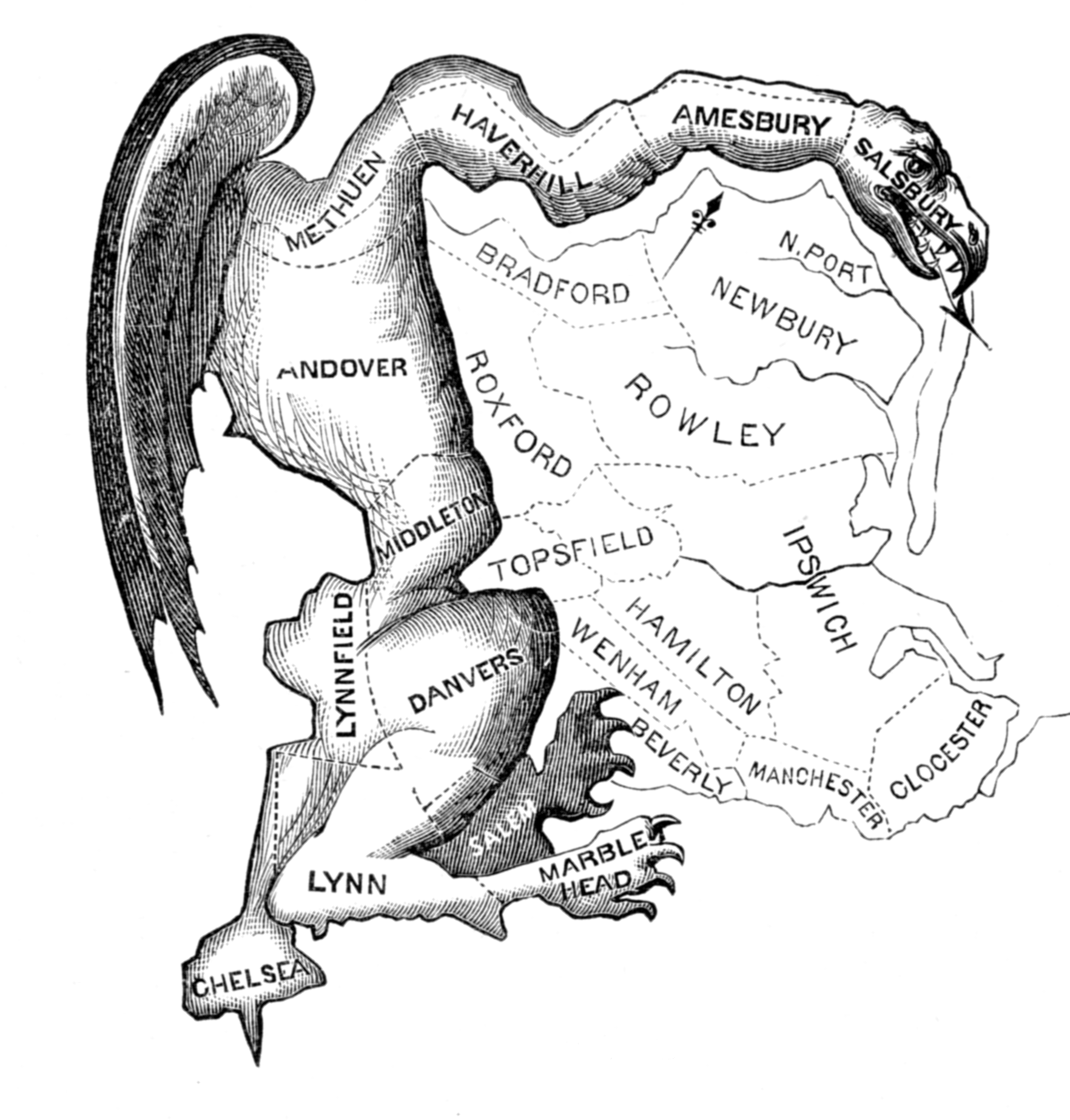

This becomes another problem, though, because the state legislators themselves decide how they will map the congressional districts they have been given; they often make decisions on the basis of partisan allegiances (based on party membership and voting patterns). The intentional shifting or drawing of congressional district lines with the intent of excluding members of a political party (or a racial/ethnic group) is known as gerrymandering. Below is a political cartoon, which was used to demonstrate the effect of gerrymandering in the 1800s. Since this cartoon was created, the technique of gerrymandering has come under great criticism and debate. This is particularly true of states in the South (including Texas) that have a history or racial or partisan gerrymandering. The Voting Rights Act of 1964 required pre-clearance of any new congressional district lines but since 2012, this pre-clearance requirement has not been enforced due to a series of Supreme Court decisions.

Since the House of Representatives is based on proportional representation and the Senate has only two members per state, a senator's constituency may be much more diverse than that of a representative. This is especially true of larger and more diverse states (such as California and Texas). A congressional district generally covers only a small part of the state (except for those six states with such small populations such as North Dakota and Wyoming that only have one representative in the House).

For example, El Paso's Representative, Veronica Escobar, would have a much less diverse constituency than Texas Senators Ted Cruz and John Cornyn. Texas has 36 diverse congressional districts while it only has two senators who must represent the interests of the entire state. So the intensely diverse and massively large population of Texas is represented by these two senators (who also are seen as highly conservative).

Why are the House and Senate So Different?

Have you ever noticed that major bills are often debated and voted on by the House in a single day, while the Senate's deliberations on the same bill take weeks? Again, this reflects the Founding Fathers' intent that the House and Senate not be carbon-copies of each other. By designing differences into the House and Senate, the Founders assured that all legislation would be carefully considered, taking both the short and long-term effects into account.

Why are the Differences Important?

The Founders intended that the House be seen as more closely representing the will of the people than the Senate.

To this end, they provided that members of the House - U.S. Representatives - be elected by and represent limited groups of citizens living in small geographically defined districts within each state. Senators, on the other hand, are elected by and represent all voters of their state. When the House considers a bill, individual members tend to base their votes primarily on how the bill might impact the people of their local district, while Senators tend to consider how the bill would impact the nation as a whole. This is just as the Founders intended.

All members of the House are up for election every two years. In effect, they are always running for election. This ensures that members will maintain close personal contact with their local constituents, thus remaining constantly aware of their opinions and needs, and better able to act as their advocates in Washington. Elected for six-year terms, Senators remain somewhat more insulated from the people, thus less likely to be tempted to vote according to the short-term passions of public opinion.

By setting the constitutionally-required minimum age for Senators at 30, as opposed to 25 for members of the House, the Founders hoped Senators would be more likely to consider the long-term effects of legislation and practice a more mature, thoughtful and deeply deliberative approach in their deliberations. Setting aside the validity of this "maturity" factor, the Senate undeniably does take longer to consider bills, often brings up points not considered by the House and just as often votes down bills passed easily by the House.

A famous (though perhaps fictional) simile often quoted to point out the differences between the House and Senate involves an argument between George Washington, who favored having two chambers of Congress and Thomas Jefferson, who believed a second chamber to be unnecessary. The story goes that the two Founders were arguing the issue while drinking coffee. Suddenly, Washington asked Jefferson, "Why did you pour that coffee into your saucer?" "To cool it," replied Jefferson. "Even so," said Washington, "we pour legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it."

The Senate as a Check on the House

As a check on the popularly elected House, the Senate has several distinct powers. For example, the "advice and consent" powers are a sole Senate privilege. The House, however, can initiate spending bills and has exclusive authority to impeach officials and choose the President in an Electoral College deadlock. The Senate and House are further differentiated by term lengths and the number of districts represented. Unlike the Senate, moreover, the House is more hierarchically organized. Moreover, the procedure of the House depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs, precedents, and traditions. In many cases, the House waives some of its stricter rules (including time limits on debates) by unanimous consent. With longer terms, fewer members and (in all but seven delegations) larger constituencies, senators may receive greater prestige. The Senate has traditionally been considered a less partisan chamber because it's relatively small membership might have a better chance to broker compromises.

| HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES | SENATE |

|

|

The Establishment of Congress

Article I: Establishes Congress (Legislative Branch of Government)

Congress is addressed in Article I of the U.S. Constitution. The Constitutional provisions of Article I are as follows:

Article I, Section 1:

All Legislative Powers are Vested in Congress:

Requires that Congress be bicameral, that is, it should be divided into two houses, the Senate and the House of Representatives. At the time the constitution was adopted, several states and the Continental Congress had only one lawmaking body. The creation of two legislative bodies reflected a compromise between the power of the states and the power of the people. The number of seats in the House of Representatives is based on population. The larger more urban states have more representatives than the more rural, less-populated states. But the Senate gives power to the states equally, with two senators from each state. To become law, any proposed legislation must be passed by both the House and the Senate and be approved (or at least not vetoed) by the president.

Article I, Section 2:

Composition and Rules for House:

Specifies that the House of Representatives be composed of members who are chosen every two years by the people of the states. There are only three qualifications: a representative must be at least 25 years old, have been a citizen of the United States for at least seven years, and must live in the state from which he or she is chosen. Efforts in Congress and the states to add requirements for office, such as durational residency rules or loyalty oaths, have been rejected by Congress and the courts.

In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court used the language, "chosen ... by the people of the several States" in Article I, Section 2, to recognize a federal right to vote in congressional elections. That right, along with the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, was later used by the U.S. Supreme Court to require that each congressional district contain roughly the same number of people, ensuring that one person's vote in a congressional election would be worth as much as another's.

Article I, Section 2, also creates the way in which congressional districts are to be divided among the states. A difficult and critical sticking point at the Constitutional Convention was how to count a state's population. Particularly controversial was how to count slaves for the purposes of representation and taxation. If slaves were considered property, they would not be counted at all. If they were considered people, they would be counted fully —just as women, children, and other non-voters were counted. Southern slave-owners viewed slaves as property, but they wanted them to be fully counted in order to increase their political power in Congress. After extended debate, the framers agreed to the three-fifths compromise — each slave would equal three-fifths of a person in a state's population count. (Note: The framers did not use the word slave in the document.) After the Civil War, the formula was changed with the passage of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, and Section 2 of the 14th Amendment, which repealed the three-fifths rule.

This section also establishes that every 10 years, every adult in the country must answer a survey instrument known as a census — a monumental task when people move as often as they do and when some people have no homes at all. Based on the surveys, Congress must determine how many representatives (at least one required) are to come from each state and how federal resources are to be distributed among the states. The Constitution set the number of House members from each of the original 13 states that were used until the first census was completed.

In 1929 Congress limited the House of Representatives to 435 members and established a formula to determine how many districts would be in each state. For example, after the 2000 census, Southern and Western states, including Texas, Florida, and California, gained population and thus added representatives while Northern states, such as Pennsylvania, lost several members.

Congress left it to state legislatures to draw district lines. As a result, at the time of a census, the political party in power in a state legislature is able to define new districts that favor its candidates, affecting who can win elections for the House of Representatives in the following decade. This process — redrawing district lines to favor a particular party — is often referred to as gerrymandering.

Article I, Section 2, also specifies other operating rules for the House of Representatives. When a House member dies or resigns during the term, the governor of that state may call for a special election to fill the vacancy. The House of Representatives chooses its own speaker, who is in line to become president if neither the president nor the vice president is able to serve.

Authorized to instigate impeachment proceedings against President.

Lastly, this section specifies that only the House of Representatives holds the power of impeachment. House members may charge a president, vice president or any civil officer of the United States with "Treason, Bribery or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors."(See Article II, Section 4.) A trial on the charges is then held in the Senate.

That happened during President Clinton's term. The House of Representatives investigated the president and brought charges against him. House members acted as prosecutors during an impeachment trial in the Senate. (See Article 1, Section 3.) Clinton was not convicted of the charges and he completed his second term as president.

Article I Section 3:

The Senate

Composition and Rules for Senate:

The Senate, which now has 100 members, has two senators from each state. Until 1913, senators were elected by their state legislatures. But since the adoption of Amendment XVII, senators have been elected directly by the voters of their states. To be a senator, a person must be more than 30 years old, must have been an American citizen for at least nine years, and must live in the state he or she represents. Senators may serve for an unlimited number of six-year terms.

Senatorial elections are held on a staggered basis so that one-third of the Senate is elected every two years. If a senator leaves office before the end of his or her term, Amendment XVII provides that the governor of his or her state sets the time for an election to replace that person. The state legislature may authorize the governor to temporarily fill the vacant seat.

U.S. Vice President is President of Senate and votes to break ties

The vice president of the United States is also the president of the Senate. He or she normally has no vote, but may vote in a tiebreaker if the Senate is divided on a proposed bill or nomination. The Senate also chooses officers to lead them through their work. One is the president pro tempore (president for a time), who presides over the Senate when the vice president is not available and, as is the Speaker of the House, is in the line of succession should the president or the vice president be unable to serve.

Sole power to adjudicate impeachment of President in hearing presided over by Chief Justice of Supreme Court.

Although the House of Representatives brings charges of impeachment to remove a president, vice president or another civil officer such as a federal judge, it is the Senate that is responsible for conducting the trial and deciding whether the individual is to be removed from office. The chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court presides over the impeachment trial of a president. The Senators act as the jury and two-thirds of those present must vote for removal from office. Once an official is removed, he or she may still be prosecuted criminally or sued, just like any other citizen

Article I, Section 4:

Congressional Elections

Gives state legislatures the task of determining how congressional elections are to be held. For example, the state legislature determines the scheduling of an election, how voters may register and where they may cast their ballots.

Congress has the right to change state rules and provide national protection for the right to vote. The first federal elections law, which included prohibitions on false registration, bribery and reporting false election returns, was passed after the Civil War to enforce the ban on racial discrimination in voting established by Amendment XV. With the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Congress extended the protection of the right to vote in federal, state and local elections.

As a general rule, Congress determines how frequently it will meet. The Constitution provides only that it meets at least once a year. Amendment XX, Section 2, now provides that the first meeting of Congress begin at noon on Jan. 3 of each year, unless the members specify differently.

Article I Section 5:

Congressional Checks on Behavior of Members

The House of Representatives and the Senate are each in charge of deciding whether an election of one of their members is legitimate. They may call witnesses to help them decide. Similarly, the House and Senate may establish their own rules, punish members for disorderly behavior and, if two-thirds agree, expel a member.

To do business, each chamber needs a quorum, which is a majority of members present. A full majority need not vote but must be present and capable of voting.

Both bodies must keep and publish a journal of their proceedings, including how members voted. Congress may decide that some discussions and votes are to be kept secret, but if one-fifth of the members demand that a vote be recorded, it must be. Neither the House nor the Senate may close down or move proceedings from their usual location for more than three days without the other chamber's consent.

Article I Section 6:

Restrictions Against Self-dealing by Members of Congress

Members of Congress are to be paid for their work from the U.S. Treasury. Amendment XXVII prohibits members from raising their salaries in the current session, so congressional votes on pay increases do not take effect until the next session of Congress.

Article I, Section 6, also protects legislators from arrests in civil lawsuits while they are in session, but they may be arrested in criminal matters. To prevent prosecutors and others from using the courts to intimidate a legislator because they do not like his or her views, legislators are granted immunity from criminal prosecution and civil lawsuits for the things they say and the work they do as legislators.

To ensure the separation of powers among the legislative, judicial and executive branches of government, Article I, Section 6, prohibits a senator or representative from holding any other federal office during his or her service in Congress.

Article I Section 7:

Revenue, Presidential Veto and Congressional Overrides

Revenue bills must originate in House

The House of Representatives must begin the process when it comes to raising and spending money. It is the chamber where all taxing and spending bills start. The Senate can offer changes and must ultimately approve the bills before they go to the president, but only the House may introduce a bill that involves taxes.

Presidential veto power over Congress

When proposed laws are approved by both the House and Senate, they go to the president. If the president signs the bill, it becomes law at the time of the signature, unless the bill provides for a different start date. If the president does nothing for 10 days, not including Sundays, the bill automatically becomes law, except in the last 10 days of the legislative term. In that time, the president can use a "pocket veto"; by doing nothing, the legislation is automatically vetoed.

If the president does not like the legislation, he or she can veto the bill, list objections, and send it back for reconsideration by the chamber where it originated. If the president vetoes a bill, the bill must be passed again with the votes of two-thirds of the House and the Senate for it to become law.

Override of Presidential veto requires 2/3 majority vote in both Houses.

Congress also may change the bill to make it more acceptable to the president. Although, for political reasons, presidents are cautious about vetoing legislation, the threat of a veto will often press members of Congress to work out a compromise. Similarly, if Congress has the ability to override a veto, it is likely the president will make every effort to compromise on the issue.

Article I Section 8:

Enumerated Powers

Specifies the powers of Congress in great detail. These powers are limited to those listed and those that are "necessary and proper" to carry them out. All other lawmaking powers are left to the states. The First Congress, concerned that the limited nature of the federal government was not clear enough in the original Constitution, later adopted Amendment X, which reserves to the states or to the people all the powers not specifically granted to the federal government.

Tax Power:

The most important of the specific powers that the Constitution enumerates is the power to set taxes, tariffs and other means of raising federal revenue, and to authorize the expenditure of all federal funds. In addition to the tax powers in Article I, Amendment XVI authorized Congress to establish a national income tax. The power to appropriate federal funds is known as the "power of the purse." It gives Congress great authority over the executive branch, which must appeal to Congress for all of its funding. The federal government borrows money by issuing bonds. This creates a national debt, which the United States is obligated to repay.

Commerce Clause:

Since the turn of the 20th century, federal legislation has dealt with many matters that had previously been managed by the states. In passing these laws, Congress often relies on power granted by the commerce clause, which allows Congress to regulate business activities "among the states."

The commerce clause gives Congress broad power to regulate many aspects of our economy and to pass environmental or consumer protections because so much of business today, either in manufacturing or distribution, cross state lines. But the commerce clause powers are not unlimited.

Necessary and Proper Clause:

In recent years, the U.S. Supreme Court has expressed greater concern for states’ rights. It has issued a series of rulings that limit the power of Congress to pass legislation under the commerce clause or other powers contained in Article I, Section 8. For example, these rulings have found unconstitutional federal laws aimed at protecting battered women or protecting schools from gun violence on the grounds that these types of police matters are properly managed by the states.

In addition, Congress has the power to coin money, create the postal service, maintain the army or navy, lower federal courts, and to declare war. Congress also has the responsibility of determining naturalization, how immigrants become citizens. Such laws must apply uniformly and cannot be modified by the states.

Article I Section 9:

Restrictions on Legislative Power

Specifically prohibits Congress from legislating in certain areas. In the first clause, the Constitution bars Congress from banning the importation of slaves before 1808. This, of course, became an unenforceable clause after the 13th Amendment ended slavery following the Civil War.

In the second and third clauses, the Constitution specifically guarantees rights to those accused of crimes. It provides that the privilege of a writ of habeas corpus, which allows a prisoner to challenge his or her imprisonment in court, cannot be suspended except in extreme circumstances such as rebellion or invasion, where the public is in danger. Suspension of the writ of habeas corpus has occurred only a few times in history. For example, President Lincoln suspended the writ during the Civil War. In 1871, it was suspended in nine counties in South Carolina to combat the Ku Klux Klan.

Similarly, the Constitution specifically prohibits bills of attainder — laws that are directed against a specific person or group of persons, making them automatically guilty of serious crimes, such as treason, without a normal court proceeding. The ban is intended to prevent Congress from bypassing the courts and denying criminal defendants the protections guaranteed by other parts of the Constitution.

In addition, the Constitution prohibits “ex post facto” laws — criminal laws that make an action illegal after someone has already taken it. This protection guarantees that individuals are warned ahead of time that their actions are illegal.

The provision in the fourth clause prohibiting states from imposing direct taxes was changed by Amendment XVI, which gives Congress the power to impose a federal income tax. To ensure equality among the states, the Constitution prohibits states from imposing taxes on goods coming into their state from another state and from favoring the ports of one state over the ports of others.

Article I, Section 9, also requires that Congress produce a regular accounting of the monies the federal government spends. Rejecting the monarchy of England, the Constitution also specifically prohibits Congress from granting a title of nobility to any person and prohibits public officials from accepting a title of nobility, office, or gift from any foreign country or monarch without congressional approval.

Article I Section 10:

Restrictions on State Power

Limits the power of the states. States may not enter into a treaty with a foreign nation; that power is given to the president, with the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate present. States cannot make their own money, nor can they grant any title of nobility.

As is Congress, states are prohibited from passing laws that assign guilt to a specific person or group without court proceedings (bills of attainder), that make something illegal retroactively(ex post facto laws) or that interfere with legal contracts.

No state, without approval from Congress, may collect taxes on imports or exports, build an army or keep warships in times of peace, or otherwise engage in war unless invaded or in imminent danger.

The Role of Committees in the Legislative Process

Committees are an essential part of the legislative process. Senate committees monitor on-going governmental operations, identify issues suitable for legislative review, gather and evaluate information, and recommend courses of action to the Senate.

During each two-year Congress, thousands of bills and resolutions are referred to Senate committees. To manage the volume and complexity, the Senate divides its work between standing committees, special or select committees, and joint committees. These committees are further divided into subcommittees. Of all the measures sent to committees, only a small percentage are considered. By considering and reporting on a bill, committees help to set the Senate’s agenda.

|

HOUSE COMMITTEES |

SENATE COMMITTEES |

|

Agriculture |

Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry |

|

Appropriations |

Appropriations |

|

Armed Services |

Armed Services |

|

Banking and Financial Service |

Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs |

|

Budget |

Budget |

|

Commerce |

Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

|

Education and the Workforce |

Energy and Natural Resources |

|

Government Reform |

Environment and Public Works |

|

House Administration |

Finance |

|

International Relations |

Foreign Relations |

|

Judiciary |

Governmental Affairs |

When a committee or subcommittee decides to consider a measure, it usually takes four actions.

- The committee requests written comments from relevant executive agencies.

- Hearings are held to gather additional information and views from non-committee experts.

- The committee works to perfect the measure by amending the bill or resolution.

- Once the language is agreed upon, the committee sends the measure back to the full Senate. Often it also provides a report that describes the purpose of the measure.

The Process for Enacting Laws

Study/Discussion Questions

- Why did the Founding Fathers choose a bicameral legislative system rather than a more traditional and widely used system such as the unicameral system it had under the Articles of Confederation?

- What are some of the major differences between the way members of the House of Representatives were originally selected vs. that of the Senate?

- How did the 17th Amendment change the way members of the Senate were selected?

- What impact did this have on the type of representation a Senator must provide his/her constituents?

- How are territories such as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands represented in the House? What type of representation do they have in the Senate? Explain your answer.

- What is Gerrymandering and why is it commonly used?

- What provisions did laws such as the Voting Rights Act of 1964 provide for states that had the reputation of gerrymandering? How did this change after 2012?

- How should senators accommodate the diverse population they represent in a state like Texas or California?

Sources:

Boundless. “Constituency.” Boundless Political Science. Boundless, 14 Nov. 2014. Retrieved 13 Apr. 2015 from https://www.boundless.com/political-science/textbooks/boundless-political -science-textbook/congress-11/how-congressmen-decide-82/constituency-450-11228/.

Congress: Why We Have a House and Senate. http://usgovinfo.about.com/od/uscongress/a/ whyhouseandsenate.htm.Accessed on April 13, 2015.

Gerrymandering. en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerrymandering. Accessed on April 12, 2015.'

Strausser, Jeffrey. Painless American Government. Barron's. 2004.

United States House of Representatives. http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_House_ of_Representatives. Accessed on April 12, 2015.

United States Senate. https://www.senate.gov/. Accessed on April 12, 2015.

https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/articles/article-i