4.3: The Structure and Functions of the Executive Branch

- Page ID

- 2032

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

The president of the United States of America, a title that automatically brings respect and recognition across the nation and the world. Only 45 men have held this office in the history of our country. The president is the head of state and head of government that is indirectly elected to a four-year term by the people through the Electoral College. The president heads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces.

The Presidency: Power and Limitations

On May 21, 2009, President Obama gave a speech explaining and justifying his decision to close the Guantánamo Bay detention center (prison). The facility had been established in 2002 by the Bush administration to hold detainees from the war in Afghanistan and later Iraq. President Obama spoke at the National Archives, in front of portraits of the founding fathers, pages of the Constitution open at his side. He thereby identified himself and his decision with the founding fathers, the treasured Constitution, and the rule of law.

Yet, years later, the prison remained open. The president had failed to offer a practical alternative or present one to Congress. Lawmakers had proved unwilling to approve funds to close it. The Republican National Committee had conducted a television advertising campaign implying that terrorists were going to be dumped onto the U.S. mainland, presenting a major terrorist threat.

The Powers of the Presidency

The presidency is seen as the heart of the political system. It is personalized in the president as an advocate of the national interest, chief agenda-setter, and chief legislator. [1] Scholars evaluate presidents according to such abilities as “public communication,” “organizational capacity,” “political skill,” “policy vision,” and “cognitive skill.” [2] The media, too, personalize the office and push the ideal of the bold, decisive, active, public-minded president who altruistically governs the country. [3]

Two big summer movie hits, Independence Day (1996) and Air Force One(1997) are typical: ex-soldier presidents use physical rather than legal powers against (respectively) aliens and Russian terrorists. The president’s tie comes off and heroism comes out, aided by fighter planes and machine guns. The television hit series The West Wing recycled, with a bit more realism, the image of a patriarchal president boldly putting principle ahead of expedience. [4]

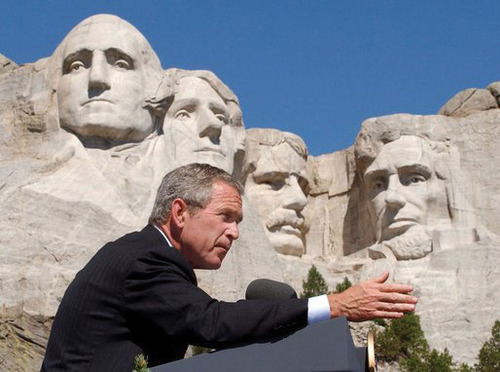

Enduring Image: Mount Rushmore

Carved into the granite rock of South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore, 7,000 feet above sea level, are the faces of Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. Sculpted between 1927 and 1941, this awe-inspiring monument achieved even greater worldwide celebrity as the setting for the hero and heroine to overcome the bad guys at the climax of Alfred Hitchcock’s classic and ever-popular film North by Northwest (1959).

This national monument did not start out devoted to American presidents. It was initially proposed to acknowledge regional heroes: General Custer, Buffalo Bill, the explorers Lewis and Clark. The sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, successfully argued that “a nation’s memorial should…have a serenity, a nobility, a power that reflects the gods who inspired them and suggests the gods they have become.” [7]

The Mount Rushmore monument is an enduring image of the American presidency by celebrating the greatness of four American presidents. The successors to Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt do their part by trying to associate themselves with the office’s magnificence and project an image of consensus rather than conflict, sometimes by giving speeches at the monument itself. A George W. Bush event placed the presidential podium at such an angle that the television camera could not help but put the incumbent in the same frame as his glorious predecessors.

The enduring image of Mount Rushmore highlights and exaggerates the importance of presidents as the decision makers in the American political system. It elevates the president over the presidency, the occupant over the office. All depends on the greatness of the individual president—which means that the enduring image often contrasts the divinity of past presidents against the fallibility of the current incumbent.

News depictions of the White House also focus on the person of the president. They portray a “single executive image” with visibility no other political participant can boast. Presidents usually get positive coverage during crises, foreign or domestic. The news media depict them speaking for and symbolically embodying the nation: giving a State of the Union address, welcoming foreign leaders, traveling abroad, representing the United States at an international conference. Ceremonial events produce laudatory coverage even during intense political controversy.

The Presidency in the Constitution

Article II of the Constitution outlines the office of president. Specific powers are few; almost all are exercised in conjunction with other branches of the federal government.

|

Article I, Section 7, Paragraph 2 |

Veto |

|

Pocket veto |

|

|

Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 1 |

“The Executive Power shall be vested in a President…” |

|

Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 7 |

Specific presidential oath of office stated explicitly (as is not the case with other offices) |

|

Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 |

Commander in chief of armed forces and state militias |

|

Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 |

Can require opinions of departmental secretaries |

|

Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 |

Reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States |

|

Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 2 |

Make treaties |

|

appoint ambassadors, executive officers, judges |

|

|

Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 3 |

Recess appointments |

|

Article II, Section 3 |

State of the Union message and recommendation of legislative measures to Congress |

|

Convene special sessions of Congress |

|

|

Receive ambassadors and other ministers |

|

|

“He shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” |

Presidents exercise only one power that cannot be limited by other branches: the pardon. So controversial decisions like President Gerald Ford’s pardon of his predecessor Richard Nixon for “crimes he committed or may have committed” or President Jimmy Carter’s blanket amnesty to all who avoided the draft during the Vietnam War could not have been overturned.

Presidents have more powers and responsibilities in foreign and defense policy than in domestic affairs. They are the commanders in chief of the armed forces; they decide how (and increasingly when) to wage war. Presidents have the power to make treaties to be approved by the Senate; the president is America’s chief diplomat. As head of state, the president speaks for the nation to other world leaders and receives ambassadors.

Read the entire Constitution at;

http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution_transcript.html.

The Constitution directs presidents to be part of the legislative process. In the annual State of the Union address, presidents point out problems and recommend legislation to Congress. Presidents can convene special sessions of Congress, possibly to “jump-start” discussion of their proposals. Presidents can veto a bill passed by Congress, returning it with written objections. Congress can then override the veto. Finally, the Constitution instructs presidents to oversee the executive branch. Along with naming judges, presidents appoint ambassadors and executive officers. These appointments require Senate confirmation. If Congress is not in session, presidents can make temporary appointments known as recess appointments without Senate confirmation, good until the end of the next session of Congress.

The Constitution’s phrase “he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” gives the president the job to oversee the implementation of laws. Thus presidents are empowered to issue executive orders to interpret and carry out legislation. They supervise other officers of the executive branch and can require them to justify their actions.

Executive Powers

The president has the power to manage national affairs and oversee the day-to-day operations of the federal government. In addition, the president has the constitutional power to issue rules, regulations and instructions called executive orders that have the binding force of law on federal agencies but do not require approval from Congress. The president also prepares the United States budget and submits it to Congress for approval.

Military Powers

The president serves as commander in chief of the United States armed forces and can call into service (federalize) National Guard in time of war or national emergency.

The president may exercise broad powers to manage the national economy and security of the United States (with oversight and approval of Congress).

Lastly, the president may send troops to other countries for hostile reasons but must get congressional confirmation within 48 hours and seek congressional approval beyond 60 days.

Legislative Powers

The president has several options when presented a bill from Congress.

- May sign a bill into law or allow to become legislation if not signed within ten days of submission

- May veto a bill and return to Congress with a “veto message”

- May “pocket veto” legislation if Congress adjourns within ten days of sending the bill to the President.

- May issue “signing statements” which express his opinion on the constitutionality of a bill’s provisions if he feels they intrude on his executive power.

As the leader of his political party, the president holds a great deal of influence over public opinion and may influence legislation through public messages and use of the media.

Appointment Powers

Before taking office, the president-elect appoints more than 6,000 new federal positions. These include top officials at U.S. government agencies, White House Staff and members of the U.S. diplomatic corps. Most of these appointments require confirmation by the Senate.

The president nominates federal judges, including members of the United States Courts of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court with advice and consent (confirmation) from Congress. This gives the president the power to exert a lasting influence on the judiciary through his appointment power because appointments are for life.

The president nominates individuals for any vacant position in federal departments or agencies (as listed in the “Plum Book” which contains more than 7,000 governmental positions which must be appointed. In addition, the president appoints his staff of aides, advisers, and assistants (which are not subject to Senate confirmation requirements).

Executive Clemency

The president has the power to pardon or commutate people convicted of federal crimes except for individuals who have been impeached and removed from office (must have been impeached by the House and removed following conviction in Senate).

Foreign Affairs

The president conducts and coordinates relations with foreign nations and appoints ambassadors, ministers, and consuls subject to confirmation from the Senate. Additionally, the president has the power to receive and recognize foreign ambassadors and other public officials. Along with the Secretary of State, the President manages all official contacts with foreign governments.

Through the Department of State and the Department of Defense, the president is responsible for the protection of Americans abroad and of foreign nationals in the United States. The president decides whether to recognize new nations and new governments, and negotiate treaties with other nations, which become binding on the United States when approved by two-thirds of the Senate. The president may also negotiate "executive agreements" with foreign powers that are not subject to Senate confirmation.

Emergency Powers

The president has implied (but not express) powers in times of national emergency.

Some Presidents (Abraham Lincoln and George W. Bush) asserted an implied power to temporarily suspend habeas corpus (the ability to be brought before a judge) in times of national emergency such as the Civil War and the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt similarly invoked emergency powers when he issued an order directing that all Japanese Americans residing on the West Coast be placed into internment camps during World War II. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld this order in Korematsu v. United States. 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

Harry Truman declared the use of emergency powers when he seized private steel mills that failed to produce steel because of a labor strike in 1952. With the Korean War ongoing, Truman asserted that he could not wage war successfully if the economy failed to provide him with the material resources necessary to keep the troops well-equipped. This action was later overturned by the Supreme Court.

Executive Privilege

Since the administration of George Washington, presidents have asserted executive privilege which gives the president the ability to withhold information from the public, Congress, and the courts in matters of national security. George Washington first claimed privilege when Congress requested to see Chief Justice John Jay's notes from an unpopular treaty negotiation with Great Britain. This power is NOT included in the Constitution but has been recognized since Washington’s tenure in office. Eventually, the assertion of executive privilege was limited by the case of the United States v. Nixon in which Richard Nixon was ordered to hand over tapes recorded in the Oval Office and eventually resigned rather than have the tapes played in open sessions of Congress. Bill Clinton also asserted executive privilege when investigated in the Monica Lewinsky case. The Supreme Court has also stated that executive privilege may not be used to avoid prosecution or some suits in civil court.

Powers Of Persuasion - "The Bully Pulpit"

The fact that the president serves as chief executive and as the recognized head of state for the United States gives him/her a great deal of persuasive power. But presidents have used a variety of methods to persuade the public and influencing the passage of legislation that they wish to see become law.

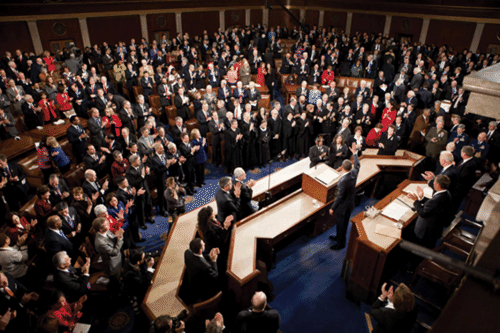

According to the Constitution, the president must give a yearly speech before a joint session of Congress. This is called the "State of the Union Speech" and is one of the most important forums for the delivery of presidential legislative agendas and "wish lists" to Congress. But of course, this agenda is not binding on Congress and only a small portion of the president's agenda will ever become law.

Another important persuasive power available to the president is the use of the office and its trappings. For instance, the president has the use of the "bully pulpit" meaning he/she can call the media together to deliver messages through press conferences or through direct addresses to the American People. Another example of the use of presidential trappings is the impact of Air Force One. When this flying presidential office rolls onto the tarmac of an airfield the president will often choose to make announcements or conduct press conferences with Air Force One in the background simply because of its impressive impact on the validity of what the president has to say.

Lastly, when the president is having difficulty getting a piece of legislation through Congress, he/she will choose to make a series of phone calls directly to those legislators who he sees as possible stalling his agenda. If that strategy doesn't impact the vote on his/her chosen legislation, the president may choose to "go public" to deliver a message directly to the people in order to activate the public to contact their representatives in Congress to vote in a certain way on a piece of legislation that is important to the president.

Congressional Limitations on Presidential Powers

Almost all presidential powers rely on what Congress does (or does not do). Presidential executive orders implement the law, but Congress can overrule such orders by changing the law. And many presidential powers are delegated powers that Congress has accorded presidents to exercise on its behalf—and that it can cut back or rescind.

Congress can challenge presidential powers single-handedly. One way is to amend the Constitution. The 22nd Amendment was enacted in the wake of the only president to serve more than two terms, the powerful Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR). Presidents now may serve no more than two terms. The last presidents to serve eight years, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, quickly became “lame ducks” after their reelection and lost momentum toward the ends of their second terms, when attention switched to contests over their successors.

Impeachment gives Congress “sole power” to remove presidents (among others) from office. [10] It works in two stages. The House decides whether or not to accuse the president of wrongdoing. If a simple majority in the House votes to impeach the president, the Senate acts as the jury, House members are prosecutors, and the chief justice presides. A two-thirds vote by the Senate is necessary for conviction, the punishment for which is removal and disqualification from office.

Prior to the 1970s, presidential impeachment was deemed the founders’ “rusted blunderbuss that will probably never be taken in hand again.” [11] Only one president (Andrew Johnson in 1868) had been impeached—over policy disagreements with Congress on the Reconstruction of the South after the Civil War. Johnson avoided removal by a single senator’s vote.

Presidential Impeachment

Read about the impeachment trial of President Johnson at;

Read about the impeachment trial of President Clinton at;

www.lib.auburn.edu/madd/docs/impeach.html.

Since the 1970s, the conflict between Congress and the president has escalated. A bipartisan majority of the House Judiciary Committee recommended the impeachment of President Nixon in 1974. Nixon surely would have been impeached and convicted had he not resigned first. President Clinton was impeached by the House in 1998, though acquitted by the Senate in 1999, for perjury and obstruction of justice in the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

Much of the public finds impeachment a standard part of the political system. For example, a June 2005 Zogby poll found that 42 percent of the public agreed with the statement “If President Bush did not tell the truth about his reasons for going to war with Iraq, Congress should consider holding him accountable through impeachment.” [12]

Impeachment can be a threat to presidents who chafe at congressional opposition or restrictions. All three impeached presidents had been accused by members of Congress of abuse of power well before allegations of law-breaking. Impeachment is handy because it refers only vaguely to official misconduct: “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

From Congress’s perspective, impeachment can work. Nixon resigned because he knew he would be removed from office. Even presidential acquittals help Congress out. Impeachment forced Johnson to pledge good behavior and thus “succeeded in its primary goal: to safeguard Reconstruction from presidential obstruction.” [13] Clinton had to go out of his way to assuage congressional Democrats, who had been far from content with several of his initiatives; by the time the impeachment trial was concluded, the president was an all-but-lame duck.

Presidential Power

Most American presidents claim inherent powers not explicitly stated but that are intrinsic to the office or implied by the language of the Constitution. They rely on three key phrases. First, in contrast to Article I’s detailed powers of Congress, Article II states that “The Executive Power shall be vested in a President.” Second, the presidential oath of office is spelled out, implying a special guardianship of the Constitution. Third, the job of ensuring that “the Laws be faithfully executed” can denote a duty to protect the country and political system.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court can and does rule on whether presidents have inherent powers. Its rulings have both expanded and limited presidential power. For instance, the justices concluded in 1936 that the president, the embodiment of the United States outside its borders, can act on its behalf in foreign policy.

But the court usually looks to congressional action (or inaction) to define when a president can invoke inherent powers. In 1952, President Harry Truman claimed inherent emergency powers during the Korean War. Facing a steel strike he said would interrupt defense production, Truman ordered his secretary of commerce to seize the major steel mills and keep production going. The Supreme Court rejected this move: “the President’s power, if any, to issue the order must stem either from an act of Congress or from the Constitution itself.”[14]

The Vice Presidency

Only two positions in the presidency are elected: the president and vice president. With ratification of the 25th Amendment in 1967, a vacancy in the latter office may be filled by the president, who appoints a vice president subject to majority votes in both the House and the Senate. This process was used twice in the 1970s. Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned amid allegations of corruption; President Nixon named House Minority Leader Gerald Ford to the post. When Nixon resigned during the Watergate scandal, Ford became president—the only person to hold the office without an election—and named former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller vice president.

The vice president’s sole duties in the Constitution are to preside over the Senate and cast tie-breaking votes, and to be ready to assume the presidency in the event of a vacancy or disability. Eight of the forty-three presidents had been vice presidents who succeeded a dead president (four times from assassinations). Otherwise, vice presidents have few official tasks. The first vice president, John Adams, told the Senate, “I am Vice President. In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.” More earthly, FDR’s first vice president, John Nance Garner, called the office “not worth a bucket of warm piss.”

In recent years, vice presidents are more publicly visible and have taken on more tasks and responsibilities. Ford and Rockefeller began this trend in the 1970s, demanding enhanced day-to-day responsibilities and staff as conditions for taking the job. Vice presidents now have a West Wing office, are given prominent assignments, and receive distinct funds for staff under their control parallel to the president’s staff. [15]

Arguably the most powerful occupant of the office ever was Dick Cheney. This former doctoral candidate in political science (at the University of Wisconsin) had been a White House chief of staff, member of Congress, and cabinet secretary. He possessed an unrivaled knowledge of the power relations within government and of how to accumulate and exercise power. As George W. Bush’s vice president, he had access to every cabinet and subcabinet meeting he wanted to attend, chaired the board charged with reviewing the budget, took on important issues (security, energy, economy), ran task forces, was involved in nominations and appointments, and lobbied Congress. [16]

The presidency is organized around two offices: The Executive Office of the President (EOP) and the White House Office (WHO). They enhance but also constrain the president’s power.

The Executive Office of the President

The Executive Office of the President (EOP) is an umbrella organization encompassing all presidential staff agencies. Most offices in the EOP, such as the office of the vice president, the National Security Council, and the Office of Management and Budget, are established by law, some positions require Senate confirmation.

Learn about the EOP at;

http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop.

Inside the EOP is the White House Office (WHO). It contains the president’s personal staff of assistants and advisors; most are exempt from Congress’s purview. Though presidents have a free hand with the personnel and structure of the WHO, its organization has been the same for decades. Starting with Nixon in 1969, each president has named a chief of staff to head and supervise the White House staff, a press secretary to interact with the news media, and a director of communication to oversee the White House message. The national security advisor is well placed to become the most powerful architect of foreign policy, rivaling or surpassing the secretary of state. New offices, such as President Bush’s creation of an office for faith-based initiatives, are rare; such positions get placed on top of or alongside old arrangements.

Even activities of a highly informal role such as the first lady, the president’s spouse, are standardized. It is no longer enough for them to host White House social events. They are brought out to travel and campaign. They are presidents’ intimate confidantes, have staffers of their own, and advocate popular policies (e.g., Lady Bird Johnson’s highway beautification, Nancy Reagan’s anti-drug crusade, and Barbara Bush’s literacy programs). Hillary Rodham Clinton faced controversy as first lady by defying expectations of being above the policy fray; she was appointed by her husband to head the task force to draft a legislative bill for a national health-care system. Clinton’s successor, Laura Bush, returned the first ladyship to a more social, less policy-minded role. Michelle Obama’s cause is healthy eating. She has gone beyond advocacy to having Walmart lower prices on the fruit and vegetables it sells and reducing the amount of fat, sugar, and salt in its foods.

Bureaucratizing the Presidency

The media and the public expect presidents to put their marks on the office and on history. But “the institution makes presidents as much if not more than presidents make the institution.” [17]

The presidency became a complex institution starting with President Franklin Roosevelt (FDR), who was elected to four terms during the Great Depression and World War II. Prior to FDR, presidents’ staffs were small. As presidents took on responsibilities and jobs, often at Congress’s initiative, the presidency grew and expanded.

Not only is the presidency bigger since FDR, but the division of labor within an administration is far more complex. Fiction and nonfiction media depict generalist staffers reporting to the president, who makes the real decisions. But the WHO is now a miniature bureaucracy. The WHO’s first staff in 1939 consisted of eight generalists: three secretaries to the president, three administrative assistants, a personal secretary, an executive clerk. Since the 1980s, the WHO has consisted of around 80 staffers; almost all either have a substantive specialty (e.g., national security, women’s initiatives, environment, health policy) or emphasize specific activities (e.g., White House legal counsel, director of press advance, public liaison, legislative liaison, chief speechwriter, director of scheduling). The White House Office adds another organization for presidents to direct—or lose track of.

The large staff in the White House, and the Old Executive Office Building next door is no guarantee of a president’s power. These staffers “make a great many decisions themselves, acting in the name of the president. In fact, the majority of White House decisions—all but the most crucial—are made by presidential assistants.” [18]

Most of these labor in anonymity unless they make impolitic remarks. For example, two of President Bush’s otherwise obscure chief economic advisors got into hot water, one for (accurately) predicting that the cost of the war in Iraq might top $200 billion, another for praising the outsourcing of jobs. [19] Relatively few White House staffers—the chief of staff, the national security advisor, the press secretary—become household names in the news, and even they are quick to be quoted saying, “as the president has said” or “the president decided.”

The political system was designed by the framers to be infrequently innovative, to act with neither efficiency nor dispatch. Authority is decentralized. Political parties are usually in conflict. Interests are diverse.[1]

Yet, as we have explained, presidents face high expectations for action. Adding to these expectations is the soaring rhetoric of their election campaigns. For example, candidate Obama promised to deal with the problems of the economy, unemployment, housing, health care, Iraq, Afghanistan, and much more.

As we have also explained, presidents do not invariably or even often have the power to meet these expectations. Consider the economy. Because the government and media report the inflation and unemployment rates and the number of new jobs created (or not created), the public is consistently reminded of these measures when judging the president’s handling of the economy. And certainly, the president does claim credit when the economy is doing well. Yet the president has far less control over the economy and these economic indicators than the media convey and many people believe.

A president’s opportunities to influence public policies depend in part on the preceding administration and the political circumstances under which the new president takes office. [2] Presidents often face intractable issues, encounter unpredictable events, have to make complex policy decisions and are beset by scandals (policy, financial, sexual).

Once in office, reality sinks in. Interviewing President Obama on The Daily Show, Jon Stewart wondered whether the president’s campaign slogan of “Yes we can” should be changed to “Yes we can, given certain conditions.” President Obama replied “I think I would say ‘yes we can, but…it’s not going to happen overnight.’” [3]

So how do presidents get things done? Presidential powers and prerogatives do offer opportunities for leadership.

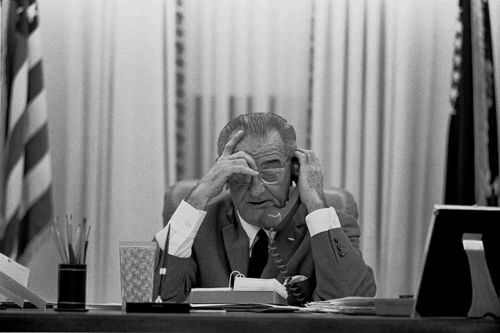

Between 1940 and 1973, six American presidents from both political parties secretly recorded just less than five thousand hours of their meetings and telephone conversations.

Check out http://millercenter.org/academic/presidentialrecordings

Presidents indicate what issues should garner most attention and action; they help set the policy agenda. They lobby Congress to pass their programs, often by campaign-like swings around the country. Their position as head of their political party enables them to keep or gain allies (and win reelection). Inside the executive branch, presidents make policies by well-publicized appointments and executive orders. They use their ceremonial position as head of state to get into the news and gain public approval, making it easier to persuade others to follow their lead.

The Roles of the President

Presidents try to set the political agenda. They call attention to issues and solutions, using constitutional powers such as calling Congress into session, recommending bills, and informing its members about the state of the union, as well as giving speeches and making news. [4]

Congress does not always defer to and sometimes spurns the president’s agenda. Its members serve smaller, more distinct constituencies for different terms. When presidents hail from the same party as the majority of Congress members, they have more influence to ensure that their ideas receive serious attention on Capitol Hill. So presidents work hard to keep or increase the number of members of their party in Congress: raising funds for the party (and their own campaign), campaigning for candidates, and throwing weight (and money) in a primary election behind the strongest or their preferred candidate. Presidential coattails—where members of Congress are carried to victory by the winning presidential candidates—are increasingly short. Most legislators win by larger margins in their district than does the president. In the elections midway through the president’s term, the president’s party generally loses seats in Congress. In 2010, despite President Obama’s efforts, the Republicans gained a whopping 63 seats and took control of the House of Representatives.

Since presidents usually have less party support in Congress in the second halves of their terms, they most often expect that Congress will be more amenable to their initiatives in their first two years. But even then, divided government, where one party controls the presidency and another party controls one or both chambers of Congress, has been common over the last fifty years. For presidents, the prospect of both a friendly House and Senate has become the exception.

Even when the White House and Congress are controlled by the same party, as with President Obama and the 2009 and 2010 Congress, presidents do not monopolize the legislative agenda. Congressional leaders, especially of the opposing party, push other issues—if only to pressure or embarrass the president. Members of Congress have made campaign promises they want to keep despite the president’s policy preferences. Interest groups with pet projects crowd in.

Nonetheless, presidents are better placed than any other individual to influence the legislative process. In particular, their high prominence in the news means that they have a powerful impact on what issues will—and will not—be considered in the political system as a whole.

What about the contents of “the president’s agenda”? The president is but one player among many shaping it. The transition from election to inauguration is just over two months (Bush had less time because of the disputed 2000 Florida vote). Presidents are preoccupied first with naming a cabinet and White House staff. To build an agenda, presidents “borrow, steal, co-opt, redraft, rename, and modify any proposal that fits their policy goals.” [5] Ideas largely come from fellow partisans outside the White House. Bills already introduced in Congress or programs proposed by the bureaucracy are handy. They have received discussion, study, and compromise that have built support. And presidents have more success getting borrowed legislation through Congress than policy proposals devised inside the White House. [6]

Crises and unexpected events affect presidents’ agenda choices. Issues pursue presidents, especially through questions and stories of White House reporters, as much as presidents pursue issues. A hugely destructive hurricane on the Gulf Coast propels issues of emergency management, poverty, and reconstruction onto the policy agenda whether a president wants them there or not.

Finally, many agenda items cannot be avoided. Presidents are charged by Congress with proposing an annual budget. Raw budget numbers represent serious policy choices. And there are ever more agenda items that never seem to get solved (e.g., energy, among many others).

After suggesting what Congress should do, presidents try to persuade legislators to follow through. But without a formal role, presidents are outsiders to the legislative process. They cannot introduce bills in Congress and must rely on members to do so.

Presidents attempt to achieve legislative accomplishments by negotiating with legislators directly or through their legislative liaison officers: White House staffers assigned to deal with Congress who provide a conduit from the president to Congress and back again. These staffers convey presidential preferences and pressure members of Congress; they also pass along members’ concerns to the White House. They count votes, line up coalitions, and suggest times for presidents to rally fellow party members. And they try to cut deals.

Legislative liaison focuses less on twisting arms than on maintaining “an era of good feelings” with Congress. Some favors are large: supporting an appropriation that benefits members’ constituencies, traveling to members’ home turf to help them raise funds for reelection, and appointing members’ cronies to high office. Others are small: inviting them up to the White House where they can talk with reporters; sending them autographed photos or extra tickets for White House tours; and allowing them to announce grants. Presidents hope the cordiality will encourage legislators to return the favor when necessary. [7]

Such good feelings are tough to maintain when presidents and the opposition party espouse conflicting policies, especially when that party has a majority in one or both chambers of Congress or both sides adopt take-it-or-leave-it stances.

When Congress sends a bill to the White House, a president can return it with objections. [8] This veto—Latin for “I forbid”—heightens the stakes. Congress can get its way only if it overrides the veto with two-thirds majorities in each chamber. Presidents who use the veto can block almost any bill they dislike; only around four percent of all vetoes have ever been successfully overridden. [9] The threat of a veto can be enough to get Congress to enact legislation that presidents prefer.

The Veto

The veto does have drawbacks for presidents:

- Vetoes alienate members of Congress who worked hard crafting a bill. So vetoes are most used as a last resort. After the 1974 elections, Republican President Ford faced an overwhelmingly Democratic Congress. A Ford legislative liaison officer recalled, “We never deliberately sat down and made the decision that we would veto sixty bills in two years.…It was the only alternative.” [10]

- The veto is a blunt instrument. It is useless if Congress does not act on legislation in the first place. In his 1993 speech proposing health-care reform, President Clinton waved a pen and vowed to veto any bill that did not provide universal coverage. Such a threat meant nothing when Congress did not pass any reform. And unlike governors of most states, presidents lack a line-item veto, which allows a chief executive to reject parts of a bill. Congress sought to give the president this power in the late 1990s, but the Supreme Court declared the law unconstitutional. [11] Presidents must take or leave bills in their totality.

- Congress can turn the veto against presidents. For example, it can pass a popular bill—especially in an election year—and dare the president to reject it. President Clinton faced such “veto bait” from the Republican Congress when he was up for reelection in 1996. The Defense of Marriage Act, which would have restricted federal recognition of marriage to opposite-sex couples, was deeply distasteful to lesbians and gay men (a key Democratic constituency) but strongly backed in public opinion polls. A Clinton veto could bring blame for killing the bill or provoke a humiliating override. Signing it ran the risk of infuriating lesbian and gay voters. Clinton ultimately signed the legislation—in the middle of the night with no cameras present.

- Veto threats can backfire. After the Democrats took over the Senate in mid-2001, they moved the “patients’ bill of rights” authorizing lawsuits against health maintenance organizations to the top of the Senate agenda. President Bush said he would veto the bill unless it incorporated strict limits on rights to sue and low caps on damages won in lawsuits. Such a visible threat encouraged a public perception that Bush was opposed to any patients’ bill of rights, or even to patients’ rights at all. [12] Veto threats thus can be ineffective or create political damage (or, as in this case, both).

Savvy presidents use “vetoes not only to block legislation but to shape it.…Vetoes are not fatal bullets but bargaining ploys.” [13] Veto threats and vetoing ceremonies become key to presidential communications in the news, which welcomes the story of Capitol Hill-versus-White House disputes, particularly under divided government. In 1996, President Clinton faced a tough welfare reform bill from a Republican Congress whose leaders dared him to veto the bill so they could claim he broke his 1992 promise to “end welfare as we know it.” Clinton vetoed the first bill; Republicans reduced the cuts but kept tough provisions denying benefits to children born to welfare recipients. Clinton vetoed this second version; Republicans shrank the cuts again and reduced the impact on children. Finally, Clinton signed the bill—and ran ads during his reelection campaign proclaiming how he had “ended welfare as we know it.”

In a signing statement, the president claims the right to ignore or refuse to enforce laws, parts of laws, or provisions of appropriations bills even though Congress has enacted them and he has signed them into law. This practice was uncommon until developed during President Ronald Reagan’s second term. It escalated under President George W. Bush, who rarely exercised the veto but instead issued almost 1,200 signing statements in eight years—about twice as many as all his predecessors combined. As one example, he rejected the requirement that he report to Congress on how he had provided safeguards against political interference in federally funded research. He justified his statements on the “inherent” power of the commander in chief and on a hitherto obscure doctrine called the unitary executive, which holds that the executive branch can overrule Congress and the courts on the basis of the president’s interpretation of the Constitution.

President Obama ordered executive officials to consult with the attorney general before relying on any of President Bush’s signing statements to bypass a law. Yet he initially issued some signing statements himself. Then, to avoid clashing with Congress, he refrained from doing so. He did claim that the executive branch could bypass what he deemed to be unconstitutional restraints on executive power. But he did not invoke the unitary executive theory. [14]

Presidential Scorecards in Congress

How often do presidents get their way on Capitol Hill? On congressional roll call votes, Congress goes along with about three-fourths of presidential recommendations; the success rate is highest earlier in the term. [15] Even on controversial, important legislation for which they expressed a preference well in advance of congressional action, presidents still do well. Congress seldom ignores presidential agenda items entirely. One study estimates that over half of presidential recommendations are substantially reflected in legislative action. [16]

Can and do presidents lead Congress, then? Not quite. Most presidential success is determined by Congress’s partisan and ideological makeup. A divided government and party polarization on Capitol Hill have made Congress more willing to disagree with the president. So recent presidents are less successful even while being choosier about bills to endorse. Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson staked out positions on well over half of congressional roll call votes. Their successors have taken positions on fewer than one-fourth of them—especially when their party did not control Congress. “Presidents, wary of an increasingly independent-minded congressional membership, have come to actively support legislation only when it is of particular importance to them, in an attempt to minimize defeat.” [17]

As chief executive, the president can move first and quickly, daring others to respond. Presidents like both the feeling of power and favorable news stories of them acting decisively. Though Congress and courts can respond, they often react slowly; many if not most presidential actions are never challenged. [18] Such direct presidential action is based in several powers: to appoint officials, to issue executive orders, to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” and to wage war.

Presidents both hire and (with the exception of regulatory commissions) fire executive officers. They also appoint ambassadors, the members of independent agencies, and the judiciary. [19]

The months between election and inauguration are consumed by the need to rapidly assemble a cabinet, a group that reports to and advises the president, made up of the heads of the 14 executive departments and whatever other positions the president accords cabinet-level rank. Finding “the right person for the job” is but one criterion. Cabinet appointees overwhelmingly hail from the president’s party; choosing fellow partisans rewards the winning coalition and helps achieve policy. [20] Presidents also try to create a team that, according to Clinton, “looks like America.” In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower was stung by the news media’s joke that his first cabinet—all male, all white—consisted of “nine millionaires and a plumber” (the latter was a union official, a short-lived labor secretary). By contrast, George W. Bush’s and Barack Obama’s cabinets had a generous complement of persons of color and women—and at least one member of the other party.

These presidential appointees must be confirmed by the Senate. If the Senate rarely votes down a nominee on the floor, it no longer rubber-stamps scandal-free nominees. A nominee may be stopped in a committee. About one out of every twenty key nominations is never confirmed, usually when a committee does not schedule it for a vote. [21]

Confirmation hearings are opportunities for senators to quiz nominees about pet projects of interest to their states, to elicit pledges to testify or provide information, and to extract promises of policy actions. [22] To win confirmation, cabinet officers pledge to be responsive and accountable to Congress. Subcabinet officials and federal judges, lacking the prominence of cabinet and Supreme Court nominees, are even more belatedly nominated and more slowly confirmed. Even senators in the president’s party routinely block nominees to protest poor treatment or win concessions.

As a result, presidents have to wait a long time before their appointees take office. Five months into President George W. Bush’s first term, one study showed that of the 494 cabinet and subcabinet positions to fill, under half had received nominations; under one-fourth had been confirmed. [23] One scholar observed, “In America today, you can get a master’s degree, build a house, bicycle across country, or make a baby in less time than it takes to put the average appointee on the job.” [24] With presidential appointments unfilled, initiatives are delayed and day-to-day running of the departments is left by default to career civil servants.

No wonder presidents can, and increasingly do, install an acting appointee or use their power to make recess appointments. [25] But such unilateral action can produce a backlash. In 2004, two nominees for the federal court had been held up by Democratic senators; when Congress was out of session for a week, President Bush named them to judgeships in recess appointments. Furious Democrats threatened to filibuster or otherwise block all Bush’s judicial nominees. Bush had no choice but to make a deal that he would not make any more judicial recess appointments for the rest of the year. [26]

Presidents make policies by executive orders. [27] This power comes from the constitutional mandate that they “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.”

Executive orders are directives to administrators in the executive branch on how to implement legislation. Courts treat them as equivalent to laws. Dramatic events have resulted from executive orders. Some famous executive orders include Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s closing the banks to avoid runs on deposits and his authorizing internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, Truman’s desegregation of the armed forces, Kennedy’s establishment of the Peace Corps, and Nixon’s creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. More typically, executive orders reorganize the executive branch and impose restrictions or directives on what bureaucrats may or may not do. The attraction of executive orders was captured by one aide to President Clinton: “Stroke of the pen. Law of the land. Kind of cool.” [28] Related ways for presidents to try to get things done are by memoranda to cabinet officers, proclamations authorized by legislation, and (usually secret) national security directives. [29]

Executive orders are imperfect for presidents; they can be easily overturned. One president can do something “with the stroke of a pen”; the next can easily undo it. President Reagan’s executive order withholding American aid to international population control agencies that provide abortion counseling was rescinded by an executive order by President Clinton in 1993, then reinstated by another executive order by President Bush in 2001—and rescinded once more by President Obama in 2009. Moreover, since executive orders are supposed to be a mere execution of what Congress has already decided, they can be superseded by congressional action.

Opportunities to act on behalf of the entire nation in international affairs are irresistible to presidents. Presidents almost always gravitate toward foreign policy as their terms progress. Domestic policy wonk Bill Clinton metamorphosed into a foreign policy enthusiast from 1993 to 2001. Even prior to 9/11, the notoriously untraveled George W. Bush was undergoing the same transformation. President Obama has been just as if not more involved in foreign policy than his predecessors.

Congress—as long as it is consulted—is less inclined to challenge presidential initiatives in foreign policy than in domestic policy. This idea that the president has greater autonomy in foreign than domestic policy is known as the “Two Presidencies Thesis.” [30]

War powers provide another key avenue for presidents to act unilaterally. After the 9/11 attacks, President Bush’s Office of Legal Counsel to the US Department of Justice argued that as commander in chief President Bush could do what was necessary to protect the American people. [31]

Since World War II, presidents have never asked Congress for (or received) a declaration of war. Instead, they rely on open-ended congressional authorizations to use force (such as for wars in Vietnam and “against terrorism”), United Nations resolutions (wars in Korea and the Persian Gulf), North American Treaty Organization (NATO) actions (peacekeeping operations and war in the former Yugoslavia), and orchestrated requests from tiny international organizations like the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (invasion of Grenada). Sometimes, presidents amass all these: in his last press conference before the start of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, President Bush invoked the congressional authorization of force, UN resolutions, and the inherent power of the president to protect the United States derived from his oath of office.

Congress can react against undeclared wars by cutting funds for military interventions. Such efforts are time-consuming and not in place until long after the initial incursion. But congressional action, or its threat, did prevent military intervention in Southeast Asia during the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975 and sped up the withdrawal of American troops from Lebanon in the mid-1980s and Somalia in 1993. [32]

Congress’s most concerted effort to restrict presidential war powers, the War Powers Act, which passed over President Nixon’s veto in 1973, may have backfired. It established that presidents must consult with Congress prior to a foreign commitment of troops, must report to Congress within forty-eight hours of the introduction of armed forces, and must withdraw such troops after sixty days if Congress does not approve. All presidents denounce this legislation. But it gives them the right to commit troops for sixty days with little more than requirements to consult and report—conditions presidents often feel free to ignore. And the presidential prerogative under the War Powers Act to commit troops on a short-term basis means that Congress often reacts after the fact. Since Vietnam, the act has done little to prevent presidents from unilaterally launching invasions. [33]

President Obama did not seek Congressional authorization before ordering the U.S. military to join attacks on the Libyan air defenses and government forces in March 2011. After the bombing campaign started, Obama sent Congress a letter contending that as commander in chief he had constitutional authority for the attacks. The White House lawyers distinguished between this limited military operation and a war.

Study/Discussion Questions

- How can the president check the power of Congress? How can Congress limit the influence of the president?

- How is the executive branch organized?

- What has happened to presidential power as the government has expanded its services and bureaucracy?

- What are the constitutional requirements to become president of the United States?

- What additional restrictions does the Constitution place on anyone who wishes to become president?

- What personal qualifications or traits make a good president?

- How has the “natural born citizen” clause of the Constitution come into question with recent presidential candidates?

- How did the 25th Amendment impact the order of succession of the presidency? What was the purpose of this constitutional amendment?

- What are the formal and informal roles of the vice president?

Sources:

[1] George C. Edwards III, The Strategic President: Persuasion and Opportunity in Presidential Leadership (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

[2] Stephen Skowronek, Presidential Leadership in Political Time (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008).

[3] Sheryl Gay Stolberg, “Hope and Change as Promised, Just Not Overnight,”New York Times, October 28, 2010, A18.

[4] Donna R. Hoffman and Alison D. Howard, Addressing the State of the Union(Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2006).

[5] Paul C. Light, The President’s Agenda: Domestic Policy Choice from Kennedy to Clinton, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 89.

[6] Andrew Rudalevige, Managing the President’s Program: Presidential Leadership and Legislative Policy Formulation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002).

[7] This section relies on Kenneth Collier, Between the Branches: The White House Office of Legislative Affairs (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997).

[8] This section relies most on Charles M. Cameron, Veto Bargaining: Presidents and the Politics of Negative Power (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000); see also Robert J. Spitzer, The Presidential Veto: Touchstone of the American Presidency (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1988).

[9] See Harold W. Stanley and Richard G. Niemi, Vital Statistics on American Politics, 1999–2000 (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1998), table 6-9.

[10] Quoted in Paul C. Light, The President’s Agenda: Domestic Policy Choice from Kennedy to Clinton, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 112.

[11] Clinton v. City of New York, 524 US 427 (1998).

[12] Frank Bruni, “Bush Strikes a Positive Tone on a Patients’ Bill of Rights,” New York Times, July 10, 2001, A12.

[13] Charles M. Cameron, Veto Bargaining: Presidents and the Politics of Negative Power (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 171.

[14] Charlie Savage, “Obama’s Embrace of a Bush Tactic Riles Congress,” New York Times, August 9, 2009, A1; and Charlie Savage, “Obama Takes a New Route to Opposing Parts of Laws,” New York Times, January 9, 2010, A9.

[15] George C. Edwards III, At the Margins: Presidential Leadership of Congress(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989); Jon R. Bond and Richard Fleisher,The President in the Legislative Arena (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990); and Mark A. Peterson, Legislating Together: The White House and Capitol Hill from Eisenhower to Reagan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990). For overall legislative productivity, the classic starting point is David R. Mayhew’sDivided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946–1990(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991).

[16] Mark A. Peterson, Legislating Together: The White House and Capitol Hill from Eisenhower to Reagan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990); and Andrew Rudalevige, Managing the President’s Program: Presidential Leadership and Legislative Policy Formulation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 136.

[17] Lyn Ragsdale, Vital Statistics on the Presidency, 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2008), 360. See also Steven A. Shull and Thomas C. Shaw, Explaining Congressional-Presidential Relations: A Multiple Perspective Approach (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999), chap. 4.

[18] Terry M. Moe, “The Presidency and the Bureaucracy: The Presidential Advantage,” in The Presidency and the Political System, 6th ed., ed. Michael Nelson (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2000), 443–74; and William G. Howell, Power without Persuasion: The Politics of Direct Presidential Action (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003).

[19] See David E. Lewis, The Politics of Presidential Appointments: Political Control and Bureaucratic Performance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008); and G. Calvin Mackenzie, ed., Innocent until Nominated: The Breakdown of the Presidential Appointments Process, ed. G. Calvin Mackenzie (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2001).

[20] Jeffrey E. Cohen, The Politics of the U.S. Cabinet: Representation in the Executive Branch, 1789–1984 (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1988).

[21] Glen S. Kurtz, Richard Fleisher, and Jon R. Bond, “From Abe Fortas to Zoë Baird: Why Some Presidential Nominations Fail in the Senate,” American Political Science Review 92 (December 1998): 871–81.

[22] G. Calvin Mackenzie, The Politics of Presidential Appointments (New York: Free Press, 1981), especially chap. 7.

[23] James Dao, “In Protest, Republican Senators Hold Up Defense Confirmations,” New York Times, May 10, 2001, A20; and Crystal Nix Hines, “Lag in Appointments Strains the Cabinet,” New York Times, June 14, 2001, A20.

[24] G. Calvin Mackenzie, “The State of the Presidential Appointments Process,” in Innocent Until Nominated: The Breakdown of the Presidential Appointments Process, ed. G. Calvin Mackenzie (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2001), 1–49 at 40–41.

[25] G. Calvin Mackenzie, “The State of the Presidential Appointments Process,” in Innocent Until Nominated: The Breakdown of the Presidential Appointments Process (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2001), 35.

[26] Neil A. Lewis, “Deal Ends Impasse over Judicial Nominees,” New York Times, May 19, 2004, A1.

[27] Kenneth R. Mayer, With the Stroke of a Pen: Executive Orders and Presidential Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

[28] Paul Begala, quoted in James Bennet, “True to Form, Clinton Shifts Energies Back to U.S. Focus,” New York Times, July 5, 1998, 10.

[29] Phillip J. Cooper, By Order of the President: The Use and Abuse of Executive Direct Action (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002).

[30] See Barbara Hinckley, Less than Meets the Eye: Foreign Policy Making and the Myth of the Assertive Congress (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994). Such deference seems largely limited to presidents’ own initiatives. See Richard Fleisher, Jon R. Bond, Glen S. Krutz, and Stephen Hanna, “The Demise of the Two Presidencies,” American Politics Quarterly 28 (2000): 3–25; and Andrew Rudalevige, Managing the President’s Program: Presidential Leadership and Legislative Policy Formulation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002),148–49.

[31] John Yoo, The Powers of War and Peace: The Constitution and Foreign Affairs after 9/11 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

[32] William G. Howell and Jon C. Pevehouse, While Dangers Gather: Congressional Checks on Presidential War Powers (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007).

[33] Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1995); Barbara Hinckley, Less than Meets the Eye: Foreign Policy Making and the Myth of the Assertive Congress (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), chap. 4.

[34] Brandice Canes-Wrone, Who Leads Whom? Presidents, Policy, and the Public(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

[35] Thomas E. Cronin and Michael A. Genovese, The Paradoxes of the American Presidency, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[36] James A. Stimson, “Public Support for American Presidents: A Cyclical Model,” Public Opinion Quarterly 40 (1976): 1–21; Samuel Kernell, “Explaining Presidential Popularity,” American Political Science Review 72 (1978): 506–22; and Richard A. Brody, Assessing the President: The Media, Elite Opinion, and Public Support (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991).

[37] Quoted in Daniel C. Hallin, ed., The Presidency, the Press and the People (La Jolla: University of California, San Diego, 1992), 21.

[38] Lawrence Jacobs and Robert Shapiro, Politicians Don’t Pander (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

[39] Joshua Green, “The Other War Room,” Washington Monthly 34, no. 4 (April 2002): 11–16; and Ben Fritz, Bryan Keefer, and Brendan Nyhan, All the President’s Spin: George W. Bush, the Media, and the Truth (New York: Touchstone, 2004).

[40] See Michael Baruch Grossman and Martha Joynt Kumar, Portraying the President: The White House and the News Media (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980); and John Anthony Maltese, Spin Control: The White House Office of Communications and the Management of Presidential News(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

[41] This discussion is based on Robert Schlesinger, White House Ghosts: Presidents and Their Speechwriters (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008).

[42] Roderick Hart, The Sound of Leadership: Presidential Communication in the Modern Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986); Barbara Hinckley, The Symbolic Presidency (New York: Routledge, 1991); and Gregory L. Hager and Terry Sullivan, “President-Centered and Presidency-Centered Explanations of Presidential Public Activity,” American Journal of Political Science 38 (November 1994): 1079–1103.

[43] David E. Sanger and Marc Lacey, “In Early Battles, Bush Learns Need for Compromises,” New York Times, April 29, 2001, A1.

[44] Samuel Kernell, Going Public: New Strategies of Presidential Leadership, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007), 2; and Stephen J. Farnsworth, Spinner in Chief: How Presidents Sell Their Policies and Themselves (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2009).

[45] George C. Edwards III, On Deaf Ears: The Limits of the Bully Pulpit (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 241.

[46] Jeffrey E. Cohen, Going Local: Presidential Leadership in the Post-Broadcast Age (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).