4.4: The Structure and Functions of the Judicial Branch

- Page ID

- 2034

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Where the Executive and Legislative branches are elected by the people, members of the Judicial Branch are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

Article III of the Constitution, which establishes the Judicial Branch, leaves Congress significant discretion to determine the shape and structure of the federal judiciary. Even the number of Supreme Court Justices is left to Congress — at times there have been as few as six, while the current number (nine, with one chief justice and eight associate justices) has only been in place since 1869.

The Creation of the Supreme Court, Lower Courts, Terms of Judges and Pay

The Judicial Power of the United States was intended to be placed solely in the hands of the Supreme Court with Congress being allowed to establish a system of lower courts as it deemed necessary. In 1789, Congress did just that when it created the United States Court System. This act created three sets of Constitutional courts starting with District Courts that would hear both criminal and civil cases of a federal nature, a set of intermediate “Circuit” courts of appeal which would review cases coming from the District Courts and the Supreme Court acting as the highest court in the land. With few exceptions, federal judges hold their Offices for life and can only be removed through a process of impeachment. Judges must be paid for their services and whenever they receive a pay raise, their pay may not be reduced as long as they stay in office. This protects the judges from being manipulated through their salary.

Judicial Authority and Jurisdiction for the Federal Courts

Section 2 of Article III describes the jurisdiction of the federal courts. Jurisdiction is the power of a court to hear a case, so this section tells us what kinds of cases the Supreme Court and other federal courts will hear.

- All cases that arise under the Constitution, the laws of the United States or its treaties.

- All cases that affect American Ambassadors, public officials, and public consuls.

- All cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction (cases that involve national waters).

- All cases in which the United States is a party (when a state, a citizen or a foreign power sues the national government).

- All cases that involve one or more states, or the citizens of different states.

- All cases between citizens of the same state who are claiming land under grants from other states.

The 11th Amendment changed some provisions of this section by placing limits on the ability of individuals to sue a state.

Original Jurisdiction

Section 2 also notes that the Supreme Court will have original jurisdiction in any case dealing with or affecting an Ambassador, Public Minister or Consul, or in which a state is a party.

Original jurisdiction is the power of a court to hear a case first. This means that, in any case dealing with these groups of public servants, the Supreme Court must hear the case first, and no lower court can do so. The number of original jurisdiction cases heard by the United States Supreme Court is very low; less than 1% of all their cases.

In addition to these original jurisdiction cases, the Supreme Court will have appellate jurisdiction in all other cases. Appellate jurisdiction is the power to hear a case AFTER a lower court has already decided the case. That is what it means to hear the case on appeal. The vast majority cases heard by the United States Supreme Court today are appellate cases.

The Supreme Court is the “court of last resort” that is, the final court in which a citizen, state or other entity can have their case heard. The Supreme Court is also the only federal court to have BOTH original and appellate jurisdiction.

Right to a Jury Trial in all Cases but Impeachment

Article III Section 2 also states that in the trial of all crimes, except impeachment, the accused has a right to a trial by jury. These trials are held in the state where the crime is committed. Impeachment is the process described in the Constitution by which high officers of the U.S. government may be accused, tried, and removed from office for misconduct; the House of Representatives is responsible for the inquiry and formal accusation, and the Senate is responsible for the trial. The right to a trial by jury is also expressly listed in the 6th and 7th Amendments of the Constitution (in the Bill of Rights).

Treason

Section 3 of Article III deals with the crime of treason, first by giving us a definition of the crime, then by telling us how the crime will be tried.

Treason is defined in the Constitution as levying war against the United States, or giving aid to our enemies. This is the only crime actually defined in the Constitution. Why? The founders were afraid that people could be charged with treason, when they were really just engaging in dissent. Part of living in a democracy is the ability we all have to disagree with our government. If simply speaking out against the government were treason, then the government could quash all dissent, and we would not have a free country. By defining treason in the Constitution, the founders made sure that those accused of treason had to do more than simply say things our government or leaders didn’t like.

To be guilty of treason, they had to take actual action (make war against our government or directly help our enemies). This protects our freedom of speech from being limited. Section 3 tells us that, to be convicted of treason, there must be two witnesses to the same overt act, or that the person committing treason must confess in open court. Congress has the power to determine the punishment for treason, which ranges from five years in prison and a $10,000 fine, up to life in prison or death.

The View of the Founders on an Independent Judiciary

The major Constitutional Convention debate was over the degree of court independence. The Federalists believed the new Supreme Court would be too weak, and the Anti Federalists believed it would be too strong. But there is little doubt that both sides intended the judicial branch to be the least powerful. In Federalist 78, Alexander Hamilton argued:

The judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them. The Executive not only dispenses the honors, but holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse, but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.

But the power of the judicial branch (through its use of Judicial Review) has risen since its creation and today, it wields great power and influence through its actions and decisions

Four Types of Law

There are four basic types of law in the federal legal system. These include:

|

Kind of Law |

Sources |

|

The Constitution: Is the fundamental law of the United States. Creates the branches of government, defines the powers and limitations of each branch and defines the scope of basic rights and obligations. |

United States Constitution (Found in the United States Code) |

|

Case Law (Judicial): Based on a court’s written explanation (known as a decision or opinion) regarding how and why it applied the law to the facts of a case. Forms the basis for legal precedents (common law) that are followed by other courts and judges in similar cases. |

U.S. Supreme Court, U.S. Court of Appeals, U.S. District Courts. Cases published in the Federal Reporter and Federal Supplement |

|

Statutes (legislative): Laws enacted by the legislature (Congress) |

U.S. Statutes at Large(“Stat.”) |

|

Administrative Regulations (executive): Administrative Agencies issue rules or regulations implementing legislation which govern an agency. These rules or regulations explain or enforce a statute. Authority comes through the Executive branch of government (with the President as Chief Executive). |

U.S. Executive and Independent Agencies The Federal Register(“Fed. Reg.”) The Code of Federal Regulations (“CFR”) |

Source: https://www.law.upenn.edu/live/files/226-research-guide-federal-court-mappdf

Independent Judiciary

Independent Judiciary is is the degree to which the courts and the judges who interpret the law are allowed to make and enforce decisions without intervention from other branches of the government. For the justice system to be impartial, it must also remain independent (by a separation of powers).

Judicial review is the power of the courts to overturn laws or other actions of Congress and the Executive Branch based on their constitutionality. This principle allows courts to establish quasi-legislation (legislation created from bench) which often leads to accusations of “judicial activism”. The Constitution is actually silent on subject of judicial review so the Supreme Court gave itself and lower courts power of judicial review in case of Marbury vs. Madison. Judicial review is rarely used. In fact the Court has struck down only around 170 national laws (less than .25 percent of all passed) and around 1400 state laws in its more than 200 year history.

Judicial Interpretation

Judicial interpretation is the manner or basis used to interpret a law. Constitutional interpretation involves deciding whether or not a law should stand solely on the basis of its constitutionality (whether or not it violates a particular part of the Constitution). Statutory interpretation involves applying both national and state law to a specific case to determine whether the law(s) actually apply to the case brought in front of the court and whether or not those laws are being applied properly in that specific case. Constitutional interpretation has a much broader scope than the very specific and minute details that are considered in the case of statutory interpretation.

Judicial Activism

Judicial activism is when the court strikes down a duly enacted law created by Congress. That is its FORMAL meaning, its descriptive meaning. But in the course of politics, commentators and critics often call a decision to strike down a law “judicial activism” if they don’t like the court’s action. If they DO like the court’s decision, they don’t use that term.

Court Fundamentals

In an adversarial judicial system such as we have in the United States, the plaintiff is the party that is bringing the case before the court as a complaint or accusation against another party. The defendant is the party that has been accused of harming the plaintiff in some way. In civil cases, the plaintiff is the injured party and the defendant is the party that has been accused of doing harm to the plaintiff. In a criminal case, the plaintiff is always the government (either the state or the United States government) and the defendant is the party accused of violating the law. In both civil and criminal cases, the burden of proof is on the plaintiff and the defendant is entitled to confront his/her accusers and to a vigorous defense against the charges.

In order to win a civil case, the plaintiff must prove the case “beyond a preponderance of the evidence” meaning the evidence presented weighs more on his/her side in the eyes of the jury or the judge (if the trial is a bench trial where a jury has been waived). In a criminal case, the state must prove its case “beyond a reasonable doubt,” meaning there is no doubt in the minds of the jury that the defendant committed the crime he/she is accused of. This is a much higher burden of proof.

In order to smoothly allow cases to flow through the system, plea bargaining often occurs before court verdicts are ever reached. This happens when the defendant is allowed to plead guilty to a lesser charge and/or receive a lighter punishment in exchange for his/her plea. In such a case, the defendant must testify to his/her crimes in open court and the defendant also waives the right to an appeal.

Deferred Adjudication

Deferred adjudication occurs when the court delays sentencing pending terms of probation. When the defendant completes all terms of probation, charges may be expunged (dropped) and/or the jail time may be eliminated or reduced.

The adversarial judicial system gives both sides of a case access to the relevant information. Each of the parties must openly share any evidence or relevant information with each other. This process is called disclosure.

Double Jeopardy and Civil/Dual (Federal and State) Prosecution Cases

Currently, people can face a criminal trial and a civil trial for the same incident without triggering the Constitution’s ban on “double jeopardy” which is forbidden in the Constitution. In a similar vein, a person can be tried at both the federal and state levels for the same crime (because of its two different laws and jurisdictions).

That’s what the law says. Is the law right? What are the arguments for and against being able to be tried both in civil and criminal court?

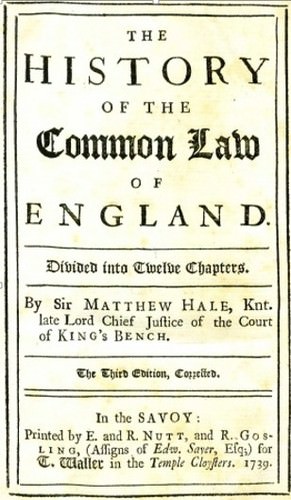

Principles of Common Law

Common Law (also known as case law or precedent) is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals that decide individual cases, as opposed to statutes adopted through the legislative process or regulations issued by the executive branch. This law is deeply rooted in the respect for the decisions and actions of previous courts and the expectation that when a ruling is made by the courts it should be respected and applied by future courts.

- Precedent (stare decisis) means “let the decision stand” in Latin. This is the principle that previously decided cases/sets of decisions should serve as a guide for future cases on the same topic. The Supreme Court strongly honored precedent in first 100 years of its existence but many decisions in the past 100 years have demonstrated modern court is more willing to overturn precedent in order to correct for violations of human rights, civil rights or states’ rights.

- Jurisdiction is the power of a court to hear a case and to make a binding legal judgment or decision based on the facts presented to the court. The Constitution and the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789 both establish the jurisdiction of the federal courts in regards to what cases they may hear and how those cases are selected or assigned to the courts.

- Collusion is the requirement that litigants in the case cannot want the same outcome

- Standing is when a petitioner has a legitimate basis for bringing the case

- Mootness is the requirement that controversy must still be relevant when the Court hears the case

- Ripeness is the opposite of mootness; with ripeness, the controversy has not started yet.

WEB LINK:

For more information on the fundamentals of common law, go to:

www.law.berkeley.edu/library/robbins/pdf/CommonLawCivilLawTraditions.pdf

Limitations on the Court's Power

The power of the Supreme Court is great but ultimately it is only a court of law. The Supreme Court does not have the power to initiate its own cases. Cases can only come to it from a lower court (except in the limited area of so-called original jurisdiction). Therefore, a justice cannot select a law or policy with which he/she disagrees and bring it to court for a ruling.

Once a decision has been made, the Supreme Court does not have the ability to enforce its rulings. This can only be done by the Executive and Legislative branches of government. When segregation in southern schools was declared unconstitutional in 1954, nothing happened in the south. It took until 1957 for the decision to actually be enforced. Though the Supreme Court had initiated a new approach in southern schools, no-one in the south wanted to enforce it and only the Federal government could do this by the use of troops.

The Supreme Court needs to maintain its position within America as the highest judicial body in the nation. Therefore it does need to be seen working as a partner with the Legislative and Executive branches as a conflict between the three would invariably diminish their standing in the eyes of the public. It is rare that the Court will totally overturn an act passed by the Legislative. The Court might seek to change parts of it piecemeal and over a period of time as this would appear to be less provocative towards an elected body. The ability of the Supreme Court to interpret the Constitution is limited as most parts of it are written in a very clear and concise way which does not leave them open to interpretation.

The greatest limitation to the Supreme Court are the politicians themselves. As the Court cannot enforce its decisions, it relies on the Federal authorities to do this. These politicians are supportive of the Constitution and even Roosevelt never thought about operating without a Supreme Court regardless of his clashes with it. Politicians must be willing to listen and abide by its decisions. What could the Supreme Court do if these politicians refused to abide by its decisions?

Power of the Supreme Court

In Federalist No. 78, Alexander Hamilton described the courts as “the least dangerous” branch of government. Yet, they do possess considerable power. For example, because of the Court’s 5–4 decision in 2002, the more than seven million public high school students engaged in “competitive” extracurricular activities—including cheerleading, Future Farmers of America, Spanish club, and choir—can be required to submit to random drug testing. Decisions such as these have proven divisive and have led to a belief by many that the Supreme Court has recently exceeded its Constitutional authority and purpose.

Discussion Question: "Do you think the Supreme Court's power has grown too large?

Many have argued that since the 1950s, the Supreme Court has changed from “the Least Dangerous Branch” to an “Imperial Judiciary.” Do you think the Supreme Court’s power has grown too large? Read the articles below and respond to this question.

www.voanews.com/content/a-13-2005-03-07-voa48-67525242/387028.html

http://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/the-most-dangerous-branch

http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2012/01/what-is-the-proper-role-of-the-courts

http://www.outsidethebeltway.com/still_the_least_dangerous_branch/

Judicial Review

The federal courts’ most significant power is judicial review. Exercising it, they can refuse to apply a state or federal law because, in their judgment, it violates the US Constitution.

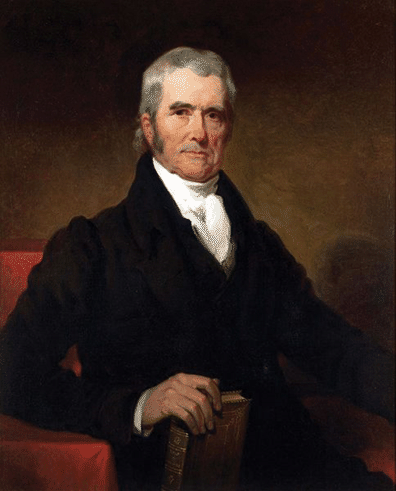

Marbury v. Madison

Judicial review was asserted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1803 in the decision of Chief Justice John Marshall in the case of Marbury v. Madison(5 US 137, 1803).

After losing the election of 1800, John Adams made a flurry of 42 appointments of justices of the peace for Washington, D.C. in the last days of his presidency. His purpose in doing so was to ensure that the judiciary would remain dominated by his Federalist party. The Senate approved the appointments, and Secretary of State John Marshall stamped the officials’ commissions with the Great Seal of the United States. But no one in the outgoing administration delivered the signed and sealed commissions to the appointees. The new president, Thomas Jefferson, instructed his secretary of state, James Madison, not to deliver them. One appointee, William Marbury, sued, asking the Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus, a court order requiring Madison to hand over the commission.

The case went directly to the Supreme Court under its original jurisdiction. John Marshall was now chief justice, having been appointed by Adams and confirmed by the Senate. He had a dilemma: a prominent Federalist, he was sympathetic to Marbury, but President Jefferson would likely refuse to obey a ruling from the Court in Marbury’s favor. However, ruling in favor of Madison would permit an executive official to defy the provisions of the law without penalty.

Marshall’s solution was a political masterpiece. The Court ruled that Marbury was entitled to his commission and that Madison had broken the law by not delivering it. But it also ruled that the part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 granting the Court the power to issue writs of mandamus was unconstitutional because it expanded the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court beyond its definition in Article III; this expansion could be done only by a constitutional amendment. Therefore, Marbury’s suit could not be heard by the Supreme Court. The decision simultaneously supported Marbury and the Federalists, did not challenge Jefferson, and relinquished the Court’s power to issue writs of mandamus. Above all, it asserted the prerogative of judicial review for the Supreme Court.

For 40 years after Marbury, the Court did not overturn a single law of Congress. And when it finally did, it was the Dred Scott decision, which dramatically damaged the Court’s power. The Court ruled that people of African descent who were slaves (and their descendants, whether or not they were slaves) were not protected by the Constitution and could never be U.S. citizens. The Court also held that the U.S. Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in federal territories.

The pace of judicial review picked up in the 1960s and continues to this day. The Supreme Court has invalidated an average of 18 federal laws per decade. The Court has displayed even less compunction about voiding state laws. For example, the famous Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas desegregation case overturned statutes from Kansas, Delaware, South Carolina, and Virginia that either required or permitted segregated public schools. The average number of state and local laws invalidated per decade is 122, although it has fluctuated from a high of 195 to a low for the period 2000–2008 of 34.

Judicial review can be seen as reinforcing the system of checks and balances. It is a way of policing the actions of Congress, the president, and state governments to make sure that they are in accord with the Constitution. But whether an act violates the Constitution is often sharply debated, not least by members of the Court.

Constraints on Judicial Power

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court and earlier was a signatory to the United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland. Early in life, Chase was a "firebrand" states-righter and revolutionary. His political views changed over his lifetime, and, in the last decades of his career, he became well known as a staunch Federalist and was impeached for allegedly letting his partisan leanings affect his court decisions. He was acquitted by the Senate and was NOT removed from office. But he remains the only Supreme Court Justice to have articles of impeachment drafted against him by the House. His is an example of philosophical and political differences that remain today.

At question then, as today, is the issue of judicial authority and power. The American system of government relies on specific checks and balances of power so as to balance the authority of the three branches of government. In this section, we will examine three types of constraints on the power of the Supreme Court and lower court judges. These are precedents, internal limitations, and external checks.

Ruling by Precedent

Judges look to precedent, previously decided cases, to guide and justify their decisions. They are expected to follow the principle of stare decisis, which is Latin for “to stand on the decision.” They identify the similarity between the case under consideration and previous ones. Then they apply the rule of law contained in the earlier case or cases to the current case. Often, one side is favored by the evidence and the precedents.

Precedents, however, have less of an influence on judicial power than would be expected. According to a study, “justices interpret precedent in order to move existing precedents closer to their preferred outcomes and to justify new policy choices.”

Precedents may erode over time. The 1954 Brown school desegregation decision overturned the 1896 Plessy decision that had upheld the constitutionality of separate but equal facilities and thus segregation. Or they may be overturned relatively quickly. In 2003, the Supreme Court by 6–3 struck down a Texas law that made homosexual acts a crime, overruling the Court’s decision seventeen years earlier upholding a similar antisodomy law in Georgia. The previous case “was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today,” Justice Kennedy wrote for the majority.

Judges may disagree about which precedents apply to a case. Consider students wanting to use campus facilities for prayer groups: if this is seen as violating the separation of church and state, they lose their case; if it is seen as freedom of speech, they win it. Precedents may allow a finding for either party, or a case may involve new areas of the law.

Internal Limitations

For the courts to exercise power, there must be a case to decide: a controversy between legitimate adversaries who have suffered or are about to suffer in some way. The case must be about the protection or enforcement of legal rights or the redress of wrongs. Judges cannot solicit cases, although they can use their decisions to signal their willingness to hear (more) cases in particular policy areas.

Judges, moreover, are expected to follow the Constitution and the law despite their policy preferences. In a speech to a bar association, Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens regretted two of his majority opinions, saying he had no choice but to uphold the federal statutes. [8] That the Supreme Court was divided on these cases indicates, however, that some of the other justices interpreted the laws differently.

A further internal limitation is that judges are obliged to explain and justify their decisions to the courts above and below. The Supreme Court’s written opinions are subject to scrutiny by other judges, law professors, lawyers, elected officials, the public, and, of course, the media.

External Checks on Power

The executive and legislative branches can check or try to check judicial power. Through their authority to nominate federal judges, presidents influence the power and direction of the courts by filling vacancies with people likely to support their policies.

They may object to specific decisions in speeches, press conferences, or written statements. In his 2010 State of the Union address, with six of the justices seated in front of him, President Obama criticized the Supreme Court’s decision that corporations have a First Amendment right to make unlimited expenditures in candidate elections. [9]

Presidents can engage in frontal assaults. Following his overwhelming reelection victory, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed to Congress in February 1937 that another justice be added to the Supreme Court for each sitting justice over the age of seventy. This would have increased the number of justices on the court from nine to fifteen. His ostensible justification was the Court’s workload and the ages of the justices. Actually, he was frustrated by the Court’s decisions, which gutted his New Deal economic programs by declaring many of its measures unconstitutional.

The president’s proposal was damned by its opponents as unwarranted meddling with the constitutionally guaranteed independence of the judiciary. It was further undermined when the justices pointed out that they were quite capable of coping with their workload, which was not at all excessive. Media coverage, editorials, and commentary were generally critical, even hostile to the proposal, framing it as “court packing” and calling it a “scheme.” The proposal seemed a rare blunder on FDR’s part. But while Congress was debating it, one of the justices shifted to the Roosevelt side in a series of regulatory cases, giving the president a majority on the court at least for these cases. This led to the famous aphorism “a switch in time saves nine.” Within a year, two of the conservative justices retired and were replaced by staunch Roosevelt supporters.

Congress can check judicial power. It overcomes a decision of the Court by writing a new law or rewriting a law to meet the Court’s constitutional objections without altering the policy. It can threaten to—and sometimes succeed in—removing a subject from the courts’ jurisdiction, or propose a constitutional amendment to undo a Court decision.

Indeed, the first piece of legislation signed by President Obama overturned a 5–4 Supreme Court 2007 decision that gave a woman a maximum of six months to seek redress after receiving the first check for less pay than her peers. [10] Named after the woman who at the end of her nineteen-year career complained that she had been paid less than men, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act extends the period to six months after any discriminatory paycheck. It also applies to anyone seeking redress for pay discrimination based on race, religion, disability, or age.

Impeachment

The Constitution grants Congress the power to impeach judges. But since the Constitution was ratified, the House has impeached only eleven federal judges, and the Senate has convicted just five of them. They were convicted for such crimes as bribery, racketeering, perjury, tax evasion, incompetence, and insanity, but not for wrongly interpreting the law.

The Supreme Court may lose power if the public perceives it as going too far. Politicians and interest groups criticize, even condemn, particular decisions. They stir up public indignation against the Court and individual justices. This happened to Chief Justice Earl Warren and his colleagues during the 1950s for their school desegregation and other civil rights decisions.

The controversial decisions of the Warren Court inspired a movement to impeach the chief justice. Do you think the founding fathers intended for the judiciary to be threatened with removal if Congress did not agree with their decisions? Explain your answer.

How the decisions and reactions to them are framed in media reports can support or undermine the Court’s legitimacy (Note the section below: "Comparing Content").

Comparing Content

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas

How a decision can be reported and framed differently is illustrated by news coverage of the 1954 Supreme Court school desegregation ruling.

The New York Times of May 18, 1954, presents the decision as monumental and historic, and school desegregation as both necessary and desirable. Southern opposition is acknowledged but downplayed, as is the difficulty of implementing the decision. The front-page headline states “High Court Bans School Segregation; 9–0 Decision Grants Time to Comply.” A second front-page article is headlined “Reactions of South.” Its basic theme is captured in two prominent paragraphs: “underneath the surface…it was evident that many Southerners recognized that the decision had laid down the legal principle rejecting segregation in public education facilities” and “that it had left open a challenge to the region to join in working out a program of necessary changes in the present bi-racial school systems.”

There is an almost page-wide photograph of the nine members of the Supreme Court. They look particularly distinguished, legitimate, authoritative, decisive, and serene.

In the South, the story was different. The Atlanta Constitution headlined its May 18, 1954, story “Court Kills Segregation in Schools: Cheap Politics, Talmadge Retorts.” By using “Kills” instead of the Times’s “Bans,” omitting the fact headlined in the Times that the decision was unanimous, and including the reaction from Georgia Governor Herman E. Talmadge, the Constitution depicted the Court’s decision far more critically than the Times. This negative frame was reinforced by the headlines of the other stories on its front page. “Georgia’s Delegation Hits Ruling” announces one; “Segregation To Continue, School Officials Predict” is a second. Another story quotes Georgia’s attorney general as saying that the “Ruling Doesn’t Apply to Georgia” and pledging a long fight.

The Times’ coverage supported and legitimized the Supreme Court’s decision. Coverage in the Constitution undermined it.

External pressure is also applied when the decisions, composition, and future appointments to the Supreme Court become issues during presidential elections. [11] In a May 6, 2008, speech at Wake Forest University, Republican presidential candidate Senator John McCain said that he would nominate for the Supreme Court “men and women with…a proven commitment to judicial restraint.” Speaking to a Planned Parenthood convention on July 17, 2007, Senator Barack Obama identified his criteria as “somebody who’s got the heart, the empathy, to recognize what it’s like…to be poor or African American or gay or disabled or old.”

Judges as Policymakers

Judges have power because they decide cases: they interpret the Constitution and laws, and select precedents. These decisions often influence, even make, public policy and have important ramifications for social conflict. For example, the Supreme Court has effectively established the ground rules for elections. In 1962 it set forth its “one person, one vote” standard for judging electoral districts. It has declared term limits for members of Congress unconstitutional. It has upheld state laws making it extremely difficult for third parties to challenge the dominance of the two major parties.

Judicial Philosophies

How willing judges are to make public policy depends in part on their judicial philosophies. Some follow judicial restraint, deciding cases on the narrowest grounds possible. In interpreting federal laws, they defer to the views expressed in Congress by those who made the laws. They shy away from invalidating laws and the actions of government officials. They tend to define some issues as political questions that should be left to the other branches of government or the voters. When the Constitution is silent, ambiguous, or open ended on a subject (e.g., “freedom of speech,” “due process of law,” and “equal protection of the laws”), they look to see whether the practice being challenged is a long-standing American tradition. They are inclined to adhere to precedent.

Judicial restraint is sometimes paired with strict constructionism. Judges apply the Constitution according to what they believe was its original meaning as understood by a reasonable person when the Constitution was written. Other judges follow a philosophy of judicial activism (although they may not call it that). Activist judges are willing to substitute their policy views for the policy actions or inaction of the other branches of government.

Judicial activism is often paired with loose constructionism, viewing the Constitution as a living document that the founders left deliberately ambiguous. In interpreting the Constitution, these judges are responsive to what they see as changes in society and its needs. A plurality of the Supreme Court found a right to privacy implicit in the Constitution and used it to overturn a Connecticut law prohibiting the use of contraceptives. [15] The justices later used that privacy right as a basis for the famous Roe v. Wade decision, “discovering” a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion.

The distinction between judicial restraint and strict constructionism on the one hand and judicial activism and loose constructionism on the other can become quite muddy. In 1995, the Supreme Court, by a 5–4 vote, struck down the Gun-Free School Zone Act—an attempt by Congress to keep guns out of schools. [16] The ruling was that Congress had overstepped its authority and that only states had the power to pass such laws. This decision by the conservative majority, interpreting the Constitution according to what it believed was the original intentions of the framers, exemplified strict constructionism. It also exemplified judicial activism: for the first time in fifty years, the Court curtailed the power of Congress under the Constitution’s commerce clause to interfere with local affairs. [17]A 5–4 conservative majority has also interpreted the Second Amendment to prohibit the regulation of guns. [18] This decision, too, could be seen as activist.

The Warren Court and Civil Rights

The Earl Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s made some of the most important civil rights decisions in American History including Brown v. Board of Education, Gideon v. Wainwright, and Cooper v. Aaron, which were unanimously decided, as well as Abington School District v. Schempp, and Engel v. Vitale.

Each case striking down religious recitations in schools with only one dissent. In an unusual action, the decision in Cooper was personally signed by all nine justices, with the three new members of the Court adding that they supported and would have joined the Court's decision in Brown v. Board. But this court’s decisions also proved to be very divisive at a time in our history when the Civil Rights movement was gaining steam. The Warren Court is an example of how the Supreme Court can use its powers of judicial review to institute policy (civil rights and civil liberties) when the legislature is unable or unwilling to do so.

Research Topic:

Conduct Research on the Earl Warren Court and its important decisions then discuss its legacy.

Do you believe this court exemplifies judicial activism or judicial restraint? What impact did the court have on our lives today? Would you describe this court’s impact as positive or negative? Explain your answer.

One doesn’t have to believe that justices are politicians in black robes to understand that some of their decisions are influenced, if not determined, by their political views. [19] Judges appointed by a Democratic president are more liberal than those appointed by a Republican president on labor and economic regulation, civil rights and liberties, and criminal justice. [20]Republican and Democratic federal appeals court judges decide differently on contentious issues such as abortion, racial integration and racial preferences, church-state relations, environmental protection, and gay rights.

On rare occasions, the Supreme Court renders a controversial decision that graphically reveals its power and is seen as motivated by political partisanship. In December 2000, the Court voted 5–4, with the five most conservative justices in the majority, that the Florida Election Code’s “intent of the voter” standard provided insufficient guidance for manually recounting disputed ballots and that there was no time left to conduct recounts under constitutionally acceptable standards. This ensured that Republican George W. Bush would become president.

The decision was widely reported and discussed in the media. Defenders framed it as principled, based on legal considerations. Critics deplored it as legally frail and politically partisan. They quoted the bitter comment of dissenting Justice Stevens: “Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.”

Study/Discussion Questions

- What role does judicial review play in our legal system? Why might it be important for the Supreme Court to have the power to decide if laws are unconstitutional?

- In Marbury v. Madison, how did Chief Justice Marshall strike a balance between asserting the Supreme Court’s authority and respecting the president’s authority? Do you think justices should take political factors into account when ruling on the law?

- Why do you think it might be important for judges to follow precedent? What do you think would happen if judges decided every case differently?

- Which of the four judicial philosophies described in the text makes the most sense to you? What do you think the advantages and disadvantages of that philosophy might be?

Sources

United States Constitution Article III. https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/articleiii Accessed 4 May, 2015.

Limits to Supreme Court Power. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/supreme_court.htm. Accessed 4 May 2015.

The Common Law and Civil Law Traditions. Berkley School of law. https://www.law.berkeley. edu/library/robbins/CommonLawCivilLawTraditions.html. Accessed 4 May 2015.

Sources of Federal Authority website. https://www.law.upenn.edu/live/files/226-research- guide-federal-court-mappdf. Accessed 4 May, 2015.

United States Code. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text. Accessed 4 May, 2015

The Federal Reporter. http://openjurist.org/f3d. Accessed 4 May, 2015.

The Federal Supplement. http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/. Accessed 4 May, 2015.

United States Congress Homepage. http://congress.gov. Accessed 4 May, 2015.

United States Statutes at Large. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwsl.html. Accessed 4 May, 2015.

The Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/. Accessed 4 May, 2015.

The Code of Federal Regulations. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collectionCfr.action? collectionCode=CFR. Accessed 4 May, 2015.