6.9: Citizen Movements

- Page ID

- 5876

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups striving to work toward a common social goal. While most of us learned about social movements in history classes, we tend to take for granted the fundamental changes they caused. But from the anti-tobacco movement that has worked to outlaw smoking in public buildings and to raise the cost of cigarettes, to uprisings about police brutality, historical and contemporary movements have created social change.

Levels of Social Movements

Movements happen in our towns, in our nation, and around the world. Let’s take a look at examples of social movements, from local to global. No doubt you can think of others on all of these levels, especially since modern technology has allowed us a near-constant stream of information about the quest for social change around the world.

Local

Chicago is a city of highs and lows, from corrupt politicians and failing schools to innovative education programs and a thriving arts scene. Not surprisingly, it has been home to a number of social movements over time. Currently, AREA Chicago is a social movement focused on “building a socially just city” (AREA Chicago 2011). The organization seeks to “create relationships and sustain community through art, research, education, and activism” (AREA Chicago 2011). The movement offers online tools like the Radicalendar––a calendar for getting radical and connected––and events such as an alternative to the traditional Independence Day picnic. Through its offerings, AREA Chicago gives local residents a chance to engage in a movement to help build a socially just city.

State

At the other end of the political spectrum from AREA Chicago is the Texas Secede! social movement in Texas. This statewide organization promotes the idea that Texas can and should secede from the United States to become an independent republic. The organization, which as of 2014 has over 6,000 “likes” on Facebook, references both Texas and national history in promoting secession. The movement encourages Texans to return to their rugged and individualistic roots and to stand up to what proponents believe is the theft of their rights and property by the U.S. government (Texas Secede! 2009).

National

A polarizing national issue that has helped create many activist groups is gay marriage. While the legal battle is being played out state by state, the issue is a national one. The Human Rights Campaign, a nationwide organization that advocates for LGBT civil rights, has been active for over thirty years and claims more than a million members. One focus of the organization is its Americans for Marriage Equality campaign. Using public celebrities such as athletes, musicians, and political figures, it seeks to engage the public in the issue of equal rights under the law. The campaign raises awareness of the over 1,100 different rights, benefits, and protections provided on the basis of marital status under federal law and seeks to educate the public about why these protections should be available to all committed couples regardless of gender (Human Rights Campaign 2014).

Global

Social organizations worldwide take stands on such general areas of concern as poverty, sex trafficking, and the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in food. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are sometimes formed to support such movements, such as the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movement (FOAM). Global efforts to reduce poverty are represented by the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief (OXFAM), among others. The Fair Trade movement exists to protect and support food producers in developing countries. Occupy Wall Street, although initially a local movement, also went global throughout Europe and, as the Middle East.

Historical Movements in the United States

Abolitionists

While white interest in and commitment to abolition had existed for several decades, organized antislavery advocacy had been largely restricted to models of gradual emancipation (seen in several northern states following the American Revolution) and conditional emancipation (seen in colonization efforts to remove black Americans to settlements in Africa). By the 1830s, however, a rising tide of anti-colonization sentiment among northern free blacks and middle-class evangelicals’ flourishing commitment to social reform radicalized the movement. Baptists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Congregational revivalists like Arthur and Lewis Tappan and Theodore Dwight Weld, and radical Quakers including Lucretia Mott and John Greenleaf Whittier helped push the idea of immediate emancipation onto the center stage of northern reform agendas. Inspired by a strategy known as “moral suasion,” these young abolitionists believed they could convince slaveholders to voluntarily release their slaves by appealing to their sense of Christian conscience. The result would be national redemption and moral harmony.

William Loyd Garrison’s early life and career famously illustrated this transition toward immediatism among radical Christian reformers. As a young man immersed in the reform culture of antebellum Massachusetts, Garrison had fought slavery in the 1820s by advocating for both black colonization and gradual abolition. Fiery tracts penned by black northerners David Walker and James Forten, however, convinced Garrison that African Americans possessed a hard-won right to the fruits of American liberty. So, in 1831, he established a newspaper called The Liberator, through which he organized and spearheaded an unprecedented interracial crusade dedicated to promoting immediate emancipation and black citizenship. Then, in 1833, Garrison presided as reformers from ten states came together to create the American Antislavery Society. They rested their mission for immediate emancipation “upon the Declaration of our Independence, and upon the truths of Divine Revelation,” binding their cause to both national and Christian redemption. Abolitionists fought to save slaves and their nation’s soul.

In order to accomplish their goals, abolitionists employed every method of outreach and agitation used in the social reform projects of the benevolent empire. At home in the North, abolitionists established hundreds of antislavery societies and worked with long-standing associations of black activists to establish schools, churches, and voluntary associations. Women and men of all colors were encouraged to associate together in these spaces to combat what they termed “color phobia.” Harnessing the potential of steam-powered printing and mass communication, abolitionists also blanketed the free states with pamphlets and antislavery newspapers. They blared their arguments from lyceum podiums and broadsides. Prominent individuals such as Wendell Phillips and Angelina Grimké saturated northern media with shame-inducing exposés of northern complicity in the return of fugitive slaves, and white reformers sentimentalized slave narratives that tugged at middle-class heartstrings. Abolitionists used the United States Postal Service in 1835 to inundate southern slaveholders’ with calls to emancipate their slaves in order to save their souls, and, in 1836, they prepared thousands of petitions for Congress as part of the “Great Petition Campaign.” In the six years from 1831 to 1837, abolitionist activities reached large heights.

However, such efforts encountered fierce opposition, as most Americans did not share abolitionists’ particular brand of nationalism. In fact, abolitionists remained a small, marginalized group detested by most white Americans in both the North and the South. Immediatists were attacked as the harbingers of disunion, rabble-rousers who would stir up sectional tensions and thereby imperil the American experiment of self-government. Fearful of disunion and outraged by the interracial nature of abolitionism, northern mobs smashed abolitionist printing presses and even killed a prominent antislavery newspaper editor named Elijah Lovejoy. White southerners, believing that abolitionists had incited Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831, aggressively purged antislavery dissent from the region. On the ground, abolitionists’ personal safety was threatened by violent harassment. In the halls of congress, Whigs and Democrats joined forces in 1836 to pass an unprecedented restriction on freedom of political expression known as the “gag rule,” which prohibited all discussion of abolitionist petitions in the House of Representatives.

In the face of such substantial external opposition, the abolitionist movement began to splinter. In 1839, an ideological dividion shook the foundations of organized antislavery. William Lloyd Garrison, a prominent leader, felt that the United States Constitution was a fundamentally pro-slavery document and that the present political system was irredeemable. They dedicated their efforts exclusively towards persuading the public to redeem the nation by re-establishing it on antislavery grounds. However, many abolitionists, reeling from opposition met in the 1830s, began to feel that moral suasion was no longer realistic. Instead, they believed, abolition would have to be effected through existing political processes. So, in 1839, political abolitionists split from Garrison’s American Antislavery, forming the Liberty Party under the leadership of James G. Birney. This new abolitionist society was predicated on the belief that the U.S. Constitution was actually an antislavery document that could be used to abolish the stain of slavery through the national political system.

Significantly, abolitionist factions also disagreed on the issue of women’s rights. Many abolitionists who believed full-heartedly in moral suasion nonetheless felt compelled to leave the American Antislavery Association because, in part, it elevated women to leadership positions and endorsed women’s suffrage. The more conservative members saw this as evidence that, in an effort to achieve general perfectionism, the American Antislavery Society had lost sight of its most important goal. Under the leadership of Arthur Tappan, they left to form the American and Foreign Antislavery Society. Though these disputes were ultimately mere road bumps on the long path to abolition, they did become so bitter and acrimonious that former friends cut social ties and traded public insults.

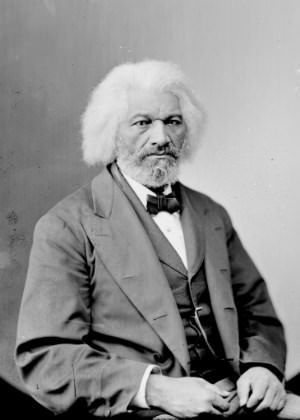

Another significant shift stemmed from the disappointments of the 1830s. Abolitionists in the 1840s increasingly moved from agendas based on reform to agendas based on resistance. While moral suasionists continued to appeal to hearts and minds, and political abolitionists launched sustained campaigns to bring abolitionist agendas to the ballot box, the entrenched and violent opposition of slaveholders and the northern public to their reform efforts encouraged abolitionists to focus on other avenues of fighting the slave power. Increasingly, for example, abolitionists focused on helping and protecting runaway slaves, and on establishing international antislavery support networks to help put pressure on the United States to abolish the institution. Frederick Douglass is one prominent example of how these two trends came together. After escaping from slavery, Douglass came to the fore of the abolitionist movement as a naturally gifted orator and a powerful narrator of his experiences in slavery. His first autobiography, published in 1845, was so widely read that it was reprinted in nine editions and translated into several languages. Douglass traveled to Great Britain in 1845, and met with famous British abolitionists like Thomas Clarkson, drumming up moral and financial support from British and Irish antislavery societies. He was neither the first nor the last runaway slave to make this voyage, but his great success abroad contributed significantly to rousing morale among weary abolitionists at home.

The model of resistance to the slave power only became more pronounced after 1850, when a long-standing Fugitive Slave Act was given new teeth. Though a legal mandate to return runway slaves had existed in U.S. federal law since 1793, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 upped the ante by harshly penalizing officials who failed to arrest runaways and private citizens who tried to help them. This law, coupled with growing concern over the possibility of that slavery would be allowed in Kansas when it was admitted as a state, made the 1850s a highly volatile and violent period of American antislavery. Reform took a backseat as armed mobs protected runaway slaves in the north and fortified abolitionists engaged in bloody skirmishes in the west. Culminating in John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, the violence of the 1850s convinced many Americans that the issue of slavery was pushing the nation to the brink of sectional cataclysm. After two decades of immediatist agitation, the idealism of revivalist perfectionism had given way to a protracted battle for the moral soul of the country.

For all of the problems that abolitionism faced, the movement was far from a failure. The prominence of African Americans in abolitionist organizations offered a powerful, if imperfect, model of interracial coexistence. While immediatists always remained a minority, their efforts paved the way for the moderately antislavery Republican Party to gain traction in the years preceding the Civil War. It is hard to imagine that Abraham Lincoln could have become president in 1860 without the ground prepared by antislavery advocates and without the presence of radical abolitionists against whom he could be cast as a moderate alternative. Though it ultimately took a civil war to break the bonds of slavery in the United States, the evangelical moral compass of revivalist Protestantism provided motivation for the embattled abolitionists.

Women's Rights

In the early 19th century, the popular understanding of gender claimed that women were the guardians of virtue and the spiritual heads of the home. Women were expected to be pious, pure, submissive, and domestic, and to pass these virtues on to their children. Historians have described these expectations as the “Cult of Domesticity,” or the “Cult of True Womanhood,” and they developed in tandem with industrialization, the market revolution, and the Second Great Awakening. In the early nineteenth century, men’s working lives increasingly took them out of the home and into the “public sphere.” At the same time, revivalism emphasized women’s unique potential and obligation to cultivate Christian values and spirituality in the “domestic sphere.” There were also real legal limits to what women could do outside of it. Women were unable to vote, men gained legal control over their wives’ property, and women with children had no legal rights over their offspring. Additionally, women could not initiate divorce, make wills, or sign contracts. Women effectively held the legal status of children.

Because the evangelical movement prominently positioned women as the guardians of moral virtue, however, many middle-class women parlayed this spiritual obligation into a more public role. Although prohibited from participating in formal politics such as voting, office holding, and making the laws that governed them, white women entered the public arena through their activism in charitable and reform organizations. Benevolent organizations dedicated to evangelizing among the poor, encouraging temperance, and curbing immorality were all considered pertinent to women’s traditional focus on family, education, and religion. Voluntary work related to labor laws, prison reform, and antislavery applied women’s roles as guardians of moral virtue to address all forms of social issues that they felt contributed to the moral decline of society. As antebellum reform and revivalism brought women into the public sphere more than ever before, women and their male allies became more attentive to the myriad forms of gender inequity in the United States.

Female education provides an example of the great strides made by and for women during the antebellum period. As part of the education reform movement lead by Horace Mann and William Holmes McGuffey, several female reformers worked tirelessly to increase women’s access to education. In 1814, Emma Willard founded the Middlebury Female Seminary with the explicit purpose of educating girls with the same rigorous curriculum used for boys of the same age. Originally running the school out of her home in Middlebury, Vermont, Willard’s efforts to expand her school struggled against financial difficulty and public opposition. It was not until 1821 that she could drum up enough private contributions to finance the opening of her Troy Female Seminary (now called Emma Willard School). The school educated future leaders of the women’s rights movement such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Mary Lyons also worked to create opportunities in women’s education, helping to establish several female educational seminaries before eventually founding Mount Holyoke College in 1837. Lyons and Willard specifically targeted the wealthy middle-class, but their work nonetheless opened doors for women that previously had remained closed.

Women’s participation in the antislavery crusade most directly inspired specific women’s rights campaigns. Many of the earliest women’s rights advocates began their activism by fighting the injustices of slavery, including Angelina Grimké, Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony. In the 1830s, women in cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia established female societies dedicated to the antislavery mission. Initially, these societies were similar to the prayer and fundraising-based projects of other reform societies. As such societies proliferated, however, their strategies changed. Women could not vote, for example, but they increasingly used their right to petition to express their antislavery grievances to the government. Impassioned women like the Grimké sisters even began to travel on lecture circuits dedicated to the cause. This latter strategy, born out of fervent antislavery advocacy, ultimately tethered the cause of women’s rights to that of abolitionism.

Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Emily Grimké were born to a wealthy family in Charleston, South Carolina, where they witnessed firsthand the horrors of slavery. Repulsed by the treatment of the slaves on their own family farm, they decided to support the antislavery movement by sharing their experiences on Northern lecture tours. They were among the earliest and most famous American women to take such a public role in the name of reform. However, when the Grimké sisters met substantial harassment and opposition to their public speaking on antislavery, they were inspired to speak out against more than the slave system. They began to address issues of women’s rights in tandem with the abolitionist cause by drawing direct comparisons between the condition of women in the United States and the condition of the slave.

As the anti-slavery movement gained momentum in the northern states in the 1830s and 1840s, so too did efforts for women’s rights. These efforts came to a head at an event that took place in London in 1840. That year, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott were among the American delegates attending the World Antislavery Convention in London. However, due to ideological disagreements between some of the abolitionists, the convention’s organizers refused to seat the female delegates or allow them to vote during the proceedings. Angered by this treatment, Stanton and Mott returned to the United States with a renewed interest in pursuing women’s rights. In 1848, they organized the Seneca Falls Convention, a two-day summit in New York state in which women’s rights advocates came together to discuss the problems facing women.

The result of the Seneca Falls Convention was the Declaration of Sentiments. Modeled on the Declaration of Independence in order to emphasize the belief that women’s rights were part of the same democratic promises on which the United States was founded, the Declaration of Sentiments outlined fifteen grievances and eleven resolutions designed to promote women’s access to civil rights. The Declaration begins, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal…” and states that “The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.” While certainly radical, this statement expressed the reformers’ belief that white men had effectively prevented white women from exercising the natural rights afforded to every human being. Sixty-eight women and thirty-two men, all of whom were already involved in some aspect of reform, signed the Declaration of Sentiments. This document ushered in nearly a century’s worth of action on behalf of women’s rights.

Women’s inability to vote was the first grievance listed in the Declaration of Sentiments, but this was not the first time that white women in New York had demanded the right to vote. Two years earlier in 1846, a group of six women petitioned the New York state legislature to amended the constitution in order to grant women the elective franchise. Yet, while suffrage would prove to a steadfast cornerstone of the women’s rights movement, antebellum activists sought more than just formal political rights. They also pursued the reformation of laws that forced women into dependency on their husbands or male family members. Women’s rights advocates rallied against laws that prohibited married women from owning property independently of their husbands and all laws that rendered married women “civilly dead.” Above all else, antebellum women’s rights advocates sought civil equality for men and women. They fought what they perceived as senseless gender discrimination, such as barring women from attending college or paying female teachers less than their male colleagues, and they argued that men and women should be held to the same moral standards.

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first of many similar gatherings promoting women’s rights across the northern states. Yet the women’s rights movement grew slowly and experienced few victories: few states reformed married women’s property laws before the Civil War, and no state was prepared to offer women the right to vote during the antebellum period. At the onset of the Civil War, women’s rights advocates temporarily threw all of their support behind abolition, allowing the cause of racial equality to temporarily trump that of gender equality. But the words of the Seneca Falls convention continued to inspire activists for generations.

The end of the decade was marked by the Women's Strike for Equality celebrating the 50th anniversary of women's right to vote. Sponsored by NOW (the National Organization for Women), the 1970 protest focused on employment discrimination, political equality, abortion, free childcare, and equality in marriage. All of these issues foreshadowed the backlash against feminist goals in the 1970s.

Hoovervilles

Desperation and frustration often create emotional responses, and the Great Depression was no exception. Throughout 1931–1932, companies trying to stay afloat sharply cut worker wages, and, in response, workers protested in increasingly bitter strikes. As the Depression unfolded, over 80 percent of automotive workers lost their jobs. Even the typically prosperous Ford Motor Company laid off two-thirds of its workforce.

In 1932, a major strike at the Ford Motor Company factory near Detroit resulted in over sixty injuries and four deaths. Often referred to as the Ford Hunger March, the event unfolded as a planned demonstration among unemployed Ford workers who, to protest their desperate situation, marched nine miles from Detroit to the company’s River Rouge plant in Dearborn. At the Dearborn city limits, local police launched tear gas at the roughly three thousand protestors, who responded by throwing stones and clods of dirt. When they finally reached the gates of the plant, protestors faced more police and firemen, as well as private security guards. As the firemen turned hoses onto the protestors, the police and security guards opened fire. In addition to those killed and injured, police arrested fifty protestors. One week later, sixty thousand mourners attended the public funerals of the four victims of what many protesters labeled police brutality. The event set the tone for worsening labor relations in the U.S.

Farmers also organized and protested, often violently. The most notable example was the Farm Holiday Association. Led by Milo Reno, this organization held significant sway among farmers in Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas. Although they never comprised a majority of farmers in any of these states, their public actions drew press attention nationwide. Among their demands, the association sought a federal government plan to set agricultural prices artificially high enough to cover the farmers’ costs, as well as a government commitment to sell any farm surpluses on the world market. To achieve their goals, the group called for farm holidays, during which farmers would neither sell their produce nor purchase any other goods until the government met their demands. However, the greatest strength of the association came from the unexpected and seldom-planned actions of its members, which included barricading roads into markets, attacking nonmember farmers, and destroying their produce. Some members even raided small town stores, destroying produce on the shelves. Members also engaged in “penny auctions,” bidding pennies on foreclosed farmland and threatening any potential buyers with bodily harm if they competed in the sale. Once they won the auction, the association returned the land to the original owner. In Iowa, farmers threatened to hang a local judge if he signed any more farm foreclosures. At least one death occurred as a direct result of these protests before they waned following the election of Franklin Roosevelt.

One of the most notable protest movements occurred toward the end of Hoover’s presidency and centered on the Bonus Expeditionary Force, or Bonus Army, in the spring of 1932. In this protest, approximately fifteen thousand World War I veterans marched on Washington to demand early payment of their veteran bonuses, which were not due to be paid until 1945. The group camped out in vacant federal buildings and set up camps in Anacostia Flats near the Capitol building.

Many veterans remained in the city in protest for nearly two months, although the U.S. Senate officially rejected their request in July. By the middle of that month, Hoover wanted them gone. He ordered the police to empty the buildings and clear out the camps, and in the exchange that followed, police fired into the crowd, killing two veterans. Fearing an armed uprising, Hoover then ordered General Douglas MacArthur, along with his aides, Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton, to forcibly remove the veterans from Anacostia Flats. The ensuing raid proved catastrophic, as the military burned down the shantytown and injured dozens of people, including a twelve-week-old infant who was killed when accidentally struck by a tear gas canister.

As Americans bore witness to photographs and newsreels of the U.S. Army forcibly removing veterans, Hoover’s popularity plummeted even further. By the summer of 1932, he was largely a defeated man. His pessimism and failure mirrored that of the nation’s citizens. America was a country in desperate need: in need of a charismatic leader to restore public confidence as well as provide concrete solutions to pull the economy out of the Great Depression.

Source: https://brewminate.com/brother-can-you-spare-a-dime-the-great-depression-1929-1932/

War Protests

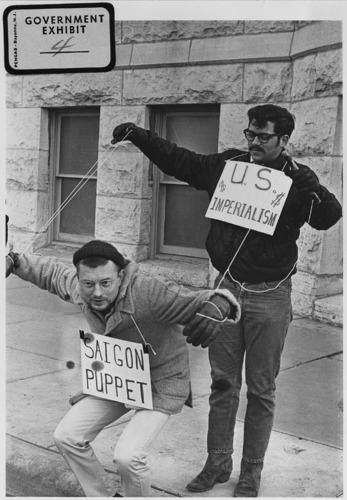

Vietnam was the first “living room war.” Television, print media, and liberal access to the battlefield provided unprecedented coverage of the war’s brutality. Americans confronted grisly images of casualties and atrocities. In 1965, CBS Evening News aired a segment in which United States Marines burned the South Vietnamese village of Cam Ne with little apparent regard for the lives of its occupants, who had been accused of aiding Viet Cong guerrillas.

While the U.S. government imposed no formal censorship on the press during Vietnam, the White House and military nevertheless used press briefings and interviews to paint a positive image of the war effort. The United States was winning the war, officials claimed. They cited numbers of enemies killed, villages secured, and South Vietnamese troops trained. American journalists in Vietnam, however, quickly realized the hollowness of such claims (the press referred to an afternoon press briefing in Saigon as “the Five O’Clock Follies”). Editors frequently toned down their reporters’ pessimism, often citing conflicting information received from their own sources, who were typically government officials. But the evidence of a stalemate mounted. American troop levels climbed yet victory remained elusive. Stories like CBS’s Cam Ne piece exposed the “credibility gap,” the yawning chasm between the claims of official sources and the reality on the ground in Vietnam. Nothing did more to expose this gap than the 1968 Tet Offensive. In January, communist forces engaged in a coordinated attack on more than one hundred American and South Vietnamese sites throughout South Vietnam, including the American embassy in Saigon. While U.S. forces repulsed the attack and inflicted heavy casualties on the Viet Cong, Tet demonstrated that, despite repeated claims by administration officials, after years of war the enemy could still strike at will anywhere in the country. Subsequent stories and images eroded public trust even further. In 1969, investigative reporter Seymour Hersh revealed that U.S. troops had massacred hundreds of civilians in the village of My Lai. More and more American voices came out against the war.

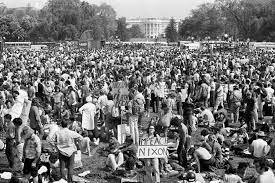

Reeling from the war’s growing unpopularity, on March 31, 1968, President Johnson announced on national television that he would not seek reelection. Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy unsuccessfully battled against Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, for the Democratic Party nomination (Kennedy was assassinated in June). At the Democratic Party’s national convention in Chicago, local police brutally assaulted protestors on national television. In a closely fought contest, Republican challenger Richard Nixon, running on a platform of “law and order” and a vague plan to end the War. Well aware of domestic pressure to wind down the war, Nixon sought, on the one hand, to appease anti-war sentiment by promising to phase out the draft, train South Vietnamese troops, and gradually withdraw American troops. He called it “Vietnamization.” At the same time, however, Nixon appealed to the so-called “silent majority” of Americans who still supported the war and opposed the anti-war movement by calling for an “honorable” end to the war (he later called it “peace with honor”). He narrowly edged Humphrey in the fall’s election.

Public assurances of American withdrawal, however, masked a dramatic escalation of the conflict. Looking to incentivize peace talks, Nixon pursued a "madman strategy" of attacking communist supply lines across Laos and Cambodia, hoping to convince the North Vietnamese that he would do anything to stop the war. Conducted without public knowledge or Congressional approval, the bombings failed to spur the peace process, and talks stalled before the Americans imposed the November 1969 deadline. News of the attacks renewed anti-war demonstrations. Police and National Guard troops killed six students in separate protests at Jackson State University in Mississippi, and, more famously, Kent State University in Ohio in 1970.

Another three years passed—and another 20,000 American troops died—before an agreement was reached. After Nixon threatened to withdraw all aid and guaranteed to enforce a treaty militarily, the North and South Vietnamese governments signed the Paris Peace Accords in January of 1973, marking the official end of U. S. force commitment to the Vietnam War. Peace was tenuous, and when war resumed North Vietnamese troops quickly overwhelmed Southern forces. By 1975, despite nearly a decade of direct American military engagement, Vietnam was united under a communist government.

The fate of South Vietnam illustrates of Nixon’s ambivalent legacy in American foreign policy. By committing to peace in Vietnam, Nixon lengthened the war and widened its impact. Nixon and other Republicans later blamed the media for America’s defeat, arguing that negative reporting undermined public support for the war. In 1971, the Nixon administration tried unsuccessfully to sue the New York Times and the Washington Post to prevent the publication of the Pentagon Papers, a confidential and damning history of U. S. involvement in Vietnam that was commissioned by the Defense Department and later leaked. Nixon faced a rising tide of congressional opposition to the war, led by prominent senators such as William Fulbright. Congress asserted unprecedented oversight of American war spending. And in 1973, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution, which dramatically reduced the president’s ability to wage war without congressional consent.

The Vietnam War profoundly shaped domestic politics. Moreover, it poisoned Americans’ perceptions of their government and its role in the world. And yet, while the anti-war demonstrations attracted considerable media attention and stand as a hallmark of the sixties counterculture so popularly remembered today, many Americans nevertheless continued to regard the war as just. Wary of the rapid social changes that reshaped American society in the 1960s and worried that anti-war protests further threatened an already tenuous civil order, a growing number of Americans criticized the protests and moved closer to a resurgent American conservatism that brewed throughout the 1970s.

Contemporary Movements in the United States

Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement encompasses social movements in the United States aimed at ending racial segregation and discrimination against African Americans and securing legal recognition and federal protection of the citizenship rights enumerated in the Constitution and federal law. While black Americans had been fighting for their rights and liberties since the time of slavery, the 1950s and ’60s witnessed critical accomplishments in their civil rights struggle.

Civil Resistance

The movement was characterized by major campaigns of civil resistance. Between 1955 and 1968, acts of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience produced crisis situations between activists and government authorities. Federal, state, and local governments, businesses, and communities often had to respond immediately to these situations that highlighted the discrimination African Americans faced. Actions included boycotts such as the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, sit-ins such as the influential Greensboro sit-ins, marches such as the Selma to Montgomery marches in Alabama and the march on Washington, as well as a wide range of other nonviolent activities.

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the Montgomery, Alabama public transit system. The campaign lasted from December 5, 1955, when Rosa Parks, an African American woman, was arrested for refusing to surrender her seat to a white person, to December 20, 1956, when a federal ruling, Browder v. Gayle, took effect and led to a Supreme Court decision that declared the Alabama and Montgomery laws requiring segregated buses to be unconstitutional. Many important figures in the Civil Rights Movement took part in the boycott, including the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ralph Abernathy.

The Greensboro sit-ins were a series of nonviolent protests in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960, which led to the Woolworth department store chain removing its policy of racial segregation in the southern United States. While not the first sit-in of the Civil Rights Movement, the Greensboro sit-ins were an instrumental action, and the most well-known sit-ins of the movement. They led to increased national sentiment at a crucial period in U.S. history. The primary event took place at the Greensboro Woolworth store; a site that is now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum.

The March on Washington was one of the largest political rallies for human rights in U.S. history. It demanded civil and economic rights for African Americans. Thousands of participants headed to Washington, D.C., on Tuesday, August 27, 1963. The next day, Martin Luther King, Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he called for an end to racism.

The three Selma-to-Montgomery marches in 1965 were part of the voting rights movement underway in Selma, Alabama. By highlighting racial injustice in the south, they contributed to passage that year of the Voting Rights Act, a landmark federal achievement of the Civil Rights Movement. Activists publicized the three protest marches to walk the 54-mile (87-km) highway from Selma to the Alabama state capital of Montgomery as showing the desire of African American citizens to exercise their constitutional right to vote, in defiance of segregationist repression.

Legislation

A critical Supreme Court decision of this phase of the Civil Rights Movement was the 1954 ruling, Brown v. Board of Education. In the spring of 1951, black students in Virginia protested their unequal status in the state’s segregated educational system. Students at Moton High School protested the overcrowded conditions and failing facilities. Some local leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had tried to persuade the students to back down from their protest against the Jim Crow laws of school segregation. When the students did not budge, the NAACP joined their battle against school segregation. The NAACP proceeded with five cases challenging the school systems; these were later combined under what is known today as Brown v. Board of Education.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that mandating, or even permitting, public schools to be segregated by race was unconstitutional. Other noted legislative achievements during this critical phase of the civil rights movement were:

- Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination based on “race, color, religion, or national origin” in employment practices and public accommodations. It ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, at the workplace, and by facilities that served the general public (known as “public accommodations”).

- The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which restored and protected voting rights. Designed to enforce the voting rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, the act secured voting rights for racial minorities throughout the country, especially in the south. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the act is considered the most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever enacted in the country.

- The Immigration and Nationality Services Act of 1965, which dramatically opened entry to the United States for immigrants other than traditional European groups.

- The Fair Housing Act of 1968 (also known as the Civil Rights Act of 1968), which banned discrimination in the sale or rental of housing.

Black Power Movement

During the Freedom Summer campaign of 1964, numerous tensions within the Civil Rights Movement came to the forefront. Many black Americans in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC; one of the major organizations of the movement) developed concerns that white activists from the north were taking over the movement. The massive presence of white students was also not reducing the amount of violence that the SNCC suffered; instead, it seemed to be increasing it. Additionally, there was profound disillusionment with Lyndon Johnson’s denial of voting status for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Meanwhile, during the work of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in Louisiana that summer, that group found the federal government would not respond to requests to enforce the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or to protect the lives of activists who challenged segregation. For the Louisiana campaign to survive it had to rely on a local African American militia called the Deacons for Defense and Justice, who used arms to repel white supremacist violence and police repression. CORE’s collaboration with the Deacons was effective against breaking Jim Crow in numerous Louisiana areas.

In 1965, the SNCC helped organize an independent political party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, in the heart of Alabama Klan territory, and permitted its black leaders to openly promote the use of armed self-defense. Meanwhile, the Deacons for Defense and Justice expanded into Mississippi and assisted Charles Evers’ NAACP chapter with a successful campaign in Natchez. The same year, the Watts Rebellion took place in Los Angeles and seemed to show that most black youths were now committed to the use of violence to protest inequality and oppression.

During the March Against Fear in 1966, the SNCC and CORE fully embraced the slogan of Black Power to describe these trends toward militancy and self-reliance. In Mississippi, Stokely Carmichael, one of the SNCC’s leaders, declared, “I’m not going to beg the white man for anything that I deserve, I’m going to take it. We need power.” Black Power was made most public, however, by the Black Panther Party, which was founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland, California, in 1966. This group followed the ideology of Malcolm X, a former member of the Nation of Islam, using a “by-any-means-necessary” approach to stopping inequality. They sought to rid African American neighborhoods of police brutality and created a 10-point plan among other efforts.

A wave of inner-city riots in black communities from 1964 through 1970 undercut support from the white community. The emergence of the Black Power movement, which lasted from about 1966 to 1975, challenged the established black leadership for its cooperative attitude and its nonviolence, and instead demanded political and economic self-sufficiency.

Many popular representations of the movement are centered on the leadership and philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr., who won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in the movement. However, historians note that the movement was too diverse to be credited to one person, organization, or strategy.

Little Rock Nine

In 1957 a crisis erupted in Little Rock, Arkansas, when Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard on September 4 to prevent entry to the nine African American students, known as the Little Rock Nine, who had sued for the right to attend the integrated Little Rock Central High School. The nine students had been chosen to attend Central High because of their excellent grades. Faubus’ resistance received the attention of President Dwight Eisenhower. Little Rock Mayor Woodrow Wilson Mann asked the president to send federal troops to enforce integration and protect the nine students. Critics had charged Eisenhower was lukewarm, at best, on the goal of desegregation of public schools. However, he federalized the National Guard in Arkansas and ordered them to return to their barracks. He also deployed elements of the 101st Airborne Division to the school to protect the students.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Social Movements

LGBT is a political ideology and social movement that advocate for the full acceptance of LGBT people in society. In these movements, LGBT people and their allies have a long history of campaigning for what is now generally called LGBT rights, sometimes also called gay rights or gay and lesbian rights. Although there is not a primary or an overarching central organization that represents all LGBT people and their interests, numerous LGBT rights organizations are active worldwide.

A commonly stated goal among these movements is social equality for LGBT people. Some have also focused on building LGBT communities or worked towards liberation for the broader society.

LGBT movements organized today are made up of a wide range of political activism and cultural activity, including lobbying, street marches, social groups, media, art, and research. Sociologist Mary Bernstein writes: "For the lesbian and gay movement, then, cultural goals include (but are not limited to) challenging dominant constructions of masculinity and femininity, homophobia, and the primacy of the gendered heterosexual nuclear family (heteronormativity). Political goals include changing laws and policies in order to gain new rights, benefits, and protections from harm." Bernstein emphasizes that activists seek both types of goals in both the civil and political spheres.

LGBT movements have often adopted a kind of identity politics that sees gay, bisexual and/or transgender people as a fixed class of people; a minority group or groups. Those using this approach aspire to liberal political goals of freedom and equal opportunity and aim to join the political mainstream on the same level as other groups in society. In arguing that sexual orientation and gender identity are innate and cannot be consciously changed, attempts to change gay, lesbian and bisexual people into heterosexuals ("conversion therapy") are generally opposed by the LGBT community. Such attempts are often based on religious beliefs that perceive gay, lesbian and bisexual activity as immoral.

Success of the early informal homosexual student groups, along with the inspiration provided by other college-based movements and the Stonewall riots, led to the proliferation of Gay Liberation Fronts on campuses across the country by the early 1970s. These first LGBT student movements passed out gay rights literature, organized social events, and sponsored lectures about the gay experience. Through their efforts, the campus climate for GLBTQ people improved. Also, by gaining institutional recognition and establishing a place on campus for GLBTQ students, the groundwork was laid for the creation of GLBTQ groups at colleges and universities throughout the country and generation of wider acceptance and tolerance.

During the 1980s, high school and junior high school students have begun to organize Gay-Straight Alliances, enabling even younger LGBT people to find support and better advocate for their needs.

As a federal republic, absent of many federal laws or court decisions, LGBT rights often are dealt with at the local or state level. Thus the rights of LGBT people in one state may be very different from the rights of LGBT people in another state.

Same-sex couples: On June 26, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all state bans on same-sex marriage, legalized it in all fifty states, and required states to honor out-of-state same-sex marriage licenses in the case Obergefell v. Hodges.

Freedom of Speech - Homosexuality as a way of expression and life is not as obscene, and thus protected under the First Amendment. However, states can reasonably regulate the time, place and manner of speech.

Civil rights - Sexual orientation is not a protected class under Federal civil rights law, but it is protected for federal civilian employees and in federal security clearance issues. The United States Supreme Court implied in Romer v. Evans that a state may not prohibit gay people from using the democratic process to get protection, prescribed by antidiscrimination law.

Education - Public schools and universities generally have to recognize an LGBT student organization, if they recognize other social or political organizations, but high school students may be required to get parental consent.

Hate crimes and criminal law - Area in which, perhaps, the biggest progression is made. Federal hate crime law now includes sexual orientation and gender identity. The Matthew Shepard Act, officially the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which expands the 1969 United States federal hate-crime law to include crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disabilities, is an Act of Congress, passed on October 22, 2009, and was signed into law by President Barack Obama on October 28, 2009, as a rider to the National Defense Authorization Act for 2010 (H.R. 2647).

The Tea Party Movement

The Tea Party movement is an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party. Members of the movement have called for lower taxes, and for a reduction of the national debt of the United States and federal budget deficit through decreased government spending.

The movement supports the small-government principle and opposes government-sponsored universal healthcare. The Tea Party movement has been described as a popular constitutional movement composed of a mixture of libertarian, right-wing populist, and conservative activism. It has sponsored multiple protests and supported various political candidates since 2009. According to the American Enterprise Institute, various polls in 2013 estimate that slightly over 10 percent of Americans identified as part of the movement.

The Tea Party movement was launched following a February 19, 2009 call by CNBC reporter Rick Santelli on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange for a "tea party," several conservative activists agreed by conference call to unite against Obama's agenda and scheduled series of protests. Supporters of the movement subsequently have had a major impact on the internal politics of the Republican Party.

Although the Tea Party is not a party in the classic sense of the word, some research suggests that members of the Tea Party Caucus vote like a significantly farther right third party in Congress. A major force behind it was Americans for Prosperity(AFP), a conservative political advocacy group founded by businessmen and political activist David H. Koch. It is unclear exactly how much money is donated to AFP by David and his brother Charles Koch. By 2019, it was reported that the conservative wing of the Republican Party "has basically shed the tea party moniker".

The movement's name refers to the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773, a watershed event in the launch of the American Revolution. The 1773 event demonstrated against taxation by the British government without political representation for the American colonists, and references to the Boston Tea Party and even costumes from the 1770s era are commonly heard and seen in the Tea Party movement.

The rights gained by these activists and others have dramatically improved the quality of life for many in the United States. Civil rights legislation did not focus solely on the right to vote or to hold public office; it also integrated schools and public accommodations, prohibited discrimination in housing and employment, and increased access to higher education. Activists for women’s rights fought for and won, greater reproductive freedom for women, better wages, and access to credit. Only a few decades ago, homosexuality was considered a mental disorder, and relations between those of the same sex was illegal in many states. Now same-sex couples have the right to legally marry.

Activism can improve people’s lives in less dramatic ways as well. Working to make cities clean up vacant lots, destroy or rehabilitate abandoned buildings, build more parks and playgrounds, pass ordinances requiring people to curb their dogs, and ban late-night noise greatly affects people’s quality of life. The actions of individual Americans can make their own lives better and improve their neighbors’ lives as well.

Source

American Government. Authored by: OpenStax. Provided by: OpenStax; Rice University. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/W8wOWXNF@12.1:Y1CfqFju@5/Preface. License: CC BY: Attribution.

(LGBT)

- Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination based on “race, color, religion, or national origin” in employment practices and public accommodations. It ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, at the workplace, and by facilities that served the general public (known as “public accommodations”).

- The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which restored and protected voting rights. Designed to enforce the voting rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, the act secured voting rights for racial minorities throughout the country, especially in the south. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the act is considered the most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever enacted in the country.

- The Immigration and Nationality Services Act of 1965, which dramatically opened entry to the United States for immigrants other than traditional European groups.

- The Fair Housing Act of 1968 (also known as the Civil Rights Act of 1968), which banned discrimination in the sale or rental of housing.