6.10: Influences on Individual's Political Actions and Attitudes

- Page ID

- 5877

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Citizen participation in a representative republic matters. The right of citizens to participate in government is an important principle of representative government. The purpose of voting–and other forms of civic engagement--is to ensure that the government serves the people and not the other way around. The pluralist theory asserts the republic cannot function without active participation by at least some citizens. No matter who we believe makes important political decisions–the majority, special interests, or a group of elites–participation through voting changes those who are in powerful positions of authority.

How Do People Become Involved

People can become civically engaged in many ways, either as individuals or as members of groups. Some forms of individual engagement require very little effort. Awareness is the first step toward engagement. Information is available from a variety of reputable media sources, such as newspapers like the Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and the New York Times; national news shows, including those offered by the Public Broadcasting Service and National Public Radio; and reputable internet sites.

Representative government cannot work effectively without the participation of informed citizens. Engaged citizens familiarize themselves with the most important issues confronting the country and with plans different candidates have for dealing with these issues. They vote for the candidates they believe will be best suited to the job, and they may join others to raise funds or campaign for those they support. They inform their representatives how they feel about important issues. Through these efforts and others, engaged citizens let their representatives know what they want and thus influence policy. Only then can government action accurately reflect the interests and concerns of the people.

Voting is a fundamental way to engage with the government. Individual votes do matter. City council members, local judges, some local law enforcement officials, mayors, state legislators, governors, and members of Congress are all chosen by popular vote. Although the president of the United States is not chosen directly by popular vote but by a group of presidential electors (informally called the Electoral College), the votes of individuals in their home states determine how these electors ultimately vote.

Responding to public opinion polls, actively contributing to a political blog, or starting a new blog are all examples of active engagement. Individuals may engage by attending political rallies, donating money to campaigns, and signing petitions.

Starting a petition of one’s own is relatively easy. Some websites connected to various causes and interest groups encourage involvement and provide petitions that can be circulated through email.

Helping people register to vote, making campaign phone calls, and driving voters to the polls on Election Day are all important activities for citizen engagement.

Some people prefer to work with groups when participating in political activities whether these are organized or informal. Group activities can be as simple as hosting a book club or a discussion group to talk about politics. Coffee Party USA provides an online forum for people from a variety of political perspectives to discuss issues of concern to them.

Individual citizens can also join interest groups promoting causes they favor. Civic engagement through organized group activity may increase the power of ordinary people to influence government actions. Even those without significant wealth or individual connections to influential people may influence the policies affecting their lives and change the direction of government through active participation in organized groups or movements. U.S. history is filled with examples of people actively challenging the existing structure of power, gaining rights for themselves and others, and protecting their interests by mutually working together to advance the causes they believe in.

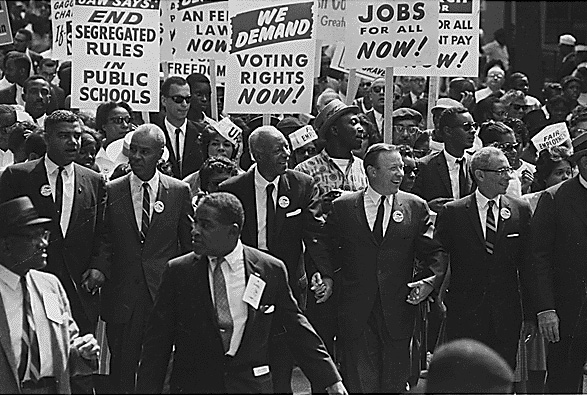

Organized groups utilize more active and direct forms of engagement including protest marches, demonstrations, and civil disobedience. Such tactics were used successfully in the African American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s and remain effective today. Other tactics, such as boycotting businesses of whose policies the activists disapproved, are also still common practice of many interest groups.

Factors that Contribute to Political Engagement

Certain factors like age, gender race, and religion help describe why people vote and who is more likely to vote. Some people are motivated to vote because they identify very strongly with one party. People can be motivated to vote based on their political ideology, or how they think the government, economy, and society should be structured. Oftentimes, people vote based on specific candidate's characteristics, experiences, or likeability. In some elections, voters are motivated to vote a certain way based on specific policy preferences, which is called issue voting.

Voting

Political participation differs notably by age. People between the ages of 35 and 65 are the most politically active. At this stage in life, people are more likely than younger people to have established homes, hold steady jobs, and be settled into communities. Those with stable community roots often have strong incentives and greater resources for becoming involved in politics. Senior citizens, people age 65 and older, also have high turnout rates of around 70 percent.

Historically, young people have been less likely to vote as they often lack the money and time to participate. However, the youth vote has been on the rise: turnout among 18 to 24-year-olds was at 36 percent in 2000, but this rose to 47 percent in 2004 and 51 percent in 2008. This rise in youth vote is partly a result of voter registration and mobilization efforts by groups like Rock the Vote. An important factor in the increase of younger voters in 2008 was the greater appeal of a younger, non-white candidate in Barack Obama. According to the Pew Research Center, 66 percent of voters under 30 chose Obama in 2008. New technology, especially the internet, is also making it easier for candidates to reach the youth. Websites such as Facebook and YouTube not only allow students to acquire information about the polls but also allow them to share their excitement over the polls and candidates.

Gender and Political Participation

Political scientists and journalists often talk about the gender gap in participation, which assumes women lag behind men in their rates of political engagement. However, the gender gap is closing for some forms of participation, such as voting. Since 1986, women have exceeded the turnout rate for men in presidential elections; 66 percent of women cast a ballot in 2008 compared with 62 percent of men. This may be due to the political prominence of issues of importance to women, such as abortion, education, and child welfare.

Racial Groups and Participation

Participation and voting differ among members of racial and ethnic groups. Discriminatory practices kept the turnout rate of African-Americans low until after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation kept black voters from the polls. Eventually, civil rights protests and litigation eliminated many barriers to voting. Today, black citizens vote at least as often as white citizens who share the same socioeconomic status. Collectively, African Americans are more involved in the American political process than other minority groups in the United States, indicated by the highest level of voter registration and participation in elections among these groups in 2004. Sixty-five percent of black voters turned out in the 2008 presidential election compared with 66 percent of white voters.

Group Participation as Civic Engagement

Joining interest groups can help facilitate civic engagement, which allows people to feel more connected to the political and social community. Some interest groups develop as grassroots movements, which often begin from the bottom up among a small number of people at the local level. Interest groups can amplify the voices of such individuals through proper organization and allow them to participate in ways that would be less effective or even impossible alone or in small numbers.

Over the past decades, there has been a rise in the number of interest groups.

Video: Interest Groups and Elections

Endorsing Candidates

Interest groups may endorse candidates for office and, if they have the resources, mobilize members and sympathizers to work and vote for them. President Bill Clinton blamed the NRA for Al Gore losing the 2000 presidential election because it influenced voters in several states, including Arkansas, West Virginia, and Gore’s home state of Tennessee. Had any of these states gone for Gore, he would have won the election.

Interest groups can promote candidates through television and radio advertisements. During the 2004 presidential election, the NRA ran a thirty-minute infomercial in battleground states favoring President George W. Bush and calling his opponent “the most anti-gun presidential nominee in United States history.” In 2008, the NRA issued ads endorsing Republican presidential candidate John McCain and his running mate, Sarah Palin.

Endorsements do carry risks. If the endorsed candidate loses, the unendorsed winner is likely to be unsympathetic to the group. Thus relatively few interest groups endorse presidential candidates and most endorsements are based on ideology.

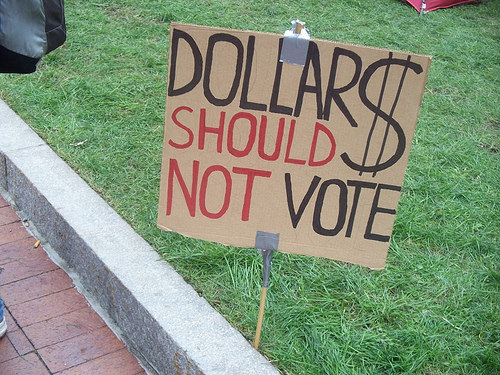

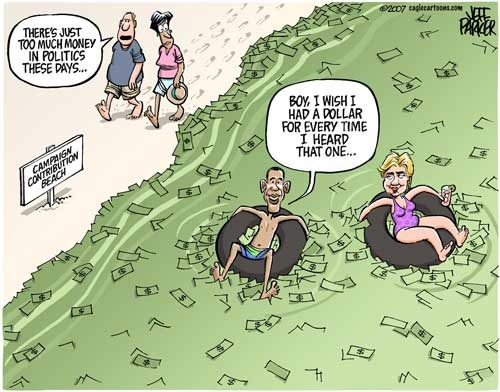

Campaign financing has become a critical issue of debate among candidates. With provisions of the Federal Election Campaign Act being weakened by court rulings and the rise of PAC and Super PAC funding sources, the amount of outside campaign financing remains an important topic.

Funding Candidates

Made possible by the 1971 Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), political action committees (PACs) are a means for organizations, including interest groups, to raise funds and contribute to candidates in federal elections. Approximately one-third of the funds received by candidates for the House of Representatives and one-fifth of funds for Senate candidates come from PACs. The details of election funding are discussed in our chapter on "Campaigns and Elections".

However, in January 2010 the Supreme Court ruled that the government cannot ban political spending by corporations in candidate elections. The court majority justified the decision on the grounds of the First Amendment’s free speech clause. The dissenters argued that allowing unlimited spending by corporations on political advertising would corrupt democracy. [16]

Many interest groups value candidates’ power above their ideology or voting record. Most PAC funds, especially from corporations, go to incumbents. Chairs and members of congressional committees and subcommittees who make policies relevant to the group are particularly favored. The case of Enron, although extreme, graphically reveals such funding. Of the 248 members of Congress on committees that investigated the 2002 accounting scandals and collapse of the giant corporation, 212 had received campaign contributions from Enron or its accounting firm, Arthur Andersen. [17]

Some interest groups fund candidates on the basis of ideology and policy preference. Ideological and public interest groups base support on candidates’ views even if their defeat is likely. Pro-life organizations mainly support Republicans; pro-choice organizations mainly support Democrats.

Many observers today believe the relationship between interest groups and political candidates has become too dependent on political campaign contributions. What do you think?

The interest group–candidate relationship is a two-way street. Many candidates actively solicit support from interest groups on the basis of an existing or the promise of a future relationship. Candidates obtain some of the funds necessary for their campaigns from interest groups; the groups who give them money get the opportunity to make their case to sympathetic legislators. A businessman defending his company’s PAC is quoted as saying, “Talking to politicians is fine, but with a little money they hear you better.” [18]

Much better. The Center for Responsive Politics shows correlations between campaign contributions and congressional voting. After the House of Representatives voted 220–215 in 2003 to pass the Medicare drug bill, the organization reported that “lawmakers who voted to approve the legislation have raised an average of roughly twice as much since 1999 from individuals and PACs associated with health insurers, HMOs [Health Maintenance Organizations] and pharmaceutical manufacturers as those who voted against the bill.” [19]

Lobbying

Besides participating in electioneering activities (political endorsements and campaign contributions), interest groups use the strategy of lobbying as their primary strategy. Lobbying is any activity that involves contacting a public official to persuade that official to support the interest of a specific group of constituents. These strategies may involve directly contacting and meeting with officials or government workers, providing information about a specific policy or issue for the purposes of educating a policy maker, or other means of direct persuasion such as email, letter writing, or telephone message campaigns.

A lobbyist may visit with officials at any level of government from local to national. For instance, a group of citizens who want to create a new zoning law prohibiting adult businesses within 1500 feet of a store might lobby their city representative, the mayor, the zoning board or even their state legislator in order to create a new law or enforce a new policy.

Today, there are many more types of lobbying available than the traditional personal meeting. Social media, e-mail and instant messaging have meant that members can be kept informed of meetings and lobbying opportunities and policymakers may be inundated with electronic messages, emails, and phone calls trying to persuade them to take a particular stand on a bill or policy. But face to face communication still tends to prove most effective in the long run.

Influencing Public Opinion

After years of being in an irreversible vegetative state, the husband of Terry Schiavo fought to have her feeding tube removed so that she could be allowed to "die with dignity." But many protesters appeared outside the hospital when a judge ordered her feeding tube removed. Congress attempted to intervene in response to intense public protest but the courts overturned them.

Many times, interest groups provide information and expert testimony in order to explain the group's interests to the policymakers and the public. Often times, this public information role generates more support for the group and heavily influences the behavior of decision makers.

Another way of influencing public opinion is the use of "grassroots" politics. This means that an issue gains support at the lowest level of an organization or society and makes its way to policymakers through public outcry from the ground up. But today, many interest groups and lobbyists have used social media and public opinion to create artificially generated grassroots movements that do not originate from the ground up but from the interest group down to the public. Many political experts have come to know this strategy as "Astroturfing" because it resembles the creation of artificial grassroots. Many grassroots organizations influence decision makers by organizing marches, demonstrations, and other forms of high-pressure and high attendance events which depend upon high levels of voluntary participation and effort.

Filing Lawsuits and Pursuing Court Intervention

Many interest groups have taken to the courts in order to change or implement public policy. Perhaps the best example of this is the famous case of Brown vs. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which was filed on behalf of Linda Brown by the NAACP. In this case, the court agreed that racially segregated schools were illegal and ordered African American students to be admitted in public schools "with all deliberate speed." Since this landmark case, many other cases have been brought before the Supreme Court by similar interest groups such as the ACLU in order to enforce constitutional provisions for equitable treatment or fair access to government resources or protections.

Benefits of Public Interest

One of the most important benefits provided by interest groups is that they give minority interests a greater voice in the political process. This was particularly true during the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s. Other political minorities, including neighborhood associations, hunters, gun owners, etc. may form their own interest groups. As an example, when officials around Austin, Texas wanted to allow the building of a Formula One racetrack. Many citizens in the area banned together and complained as a group, but the track was built anyway.

Criticism of Interest Groups

Many critics believe interest groups have been given too much power in the political process today. Influence has become synonymous with money in the modern era of lobbies, PACs and Super PACs. For instance, a well-funded group may exercise unlimited spending and influence in a political race where a smaller grassroots organization could never compete with such resources. The truth is that the size of the group in membership is not as critical as the financial resources available to the group. There are, in fact, groups that rely strictly on the financial resources of one or two major benefactors that can exert much more influence than groups with thousands of "grassroots" members.

Another criticism often placed against interest groups is that they tend to focus on one narrow issue. The defense for this would be that single issue groups help get recognition and reception to issues that, left alone, would never get attention in a purely democratic system (majority rules). But critics say this causes policy makers to take a very narrow focus and to ignore the much greater picture and agenda of national issues that impact us all. Yet another criticism is seen in the argument that interest groups often use emotional appeals rather than appealing to logical or reason-based solutions to social problems.

An even more common criticism today is that the single-issue focus of interest group based politics has led to an era of "policy gridlock" where politicians cannot come to an agreement on important issues or policies so they simply choose to ignore those issues, in effect making the decision not to make a decision. Failing to make a decision or ignoring an issue because of its controversial nature is actually a policy-making process and "non-decisions" become public policy simply by the level of inaction of decision makers.

Limiting Interest Groups

After a number of highly publicized scandals involving public officials and lobbyists, ethics and lobbying reform legislation was passed by Congress. These new rules placed stricter limits on House and Senate ethics rules for legislators and limited many types of lobbying activities.

But while these reforms were extensive and necessary, many critics have claimed that Congress has passed similar rules and legislation in the past and that these reform efforts have shown only minimal success at best. This is because it is in the nature of interest groups to find ways around such limitations and to find more ingenious ways of circumventing the system in order to continue the profitable business of brokering outside influence over the lawmaking process. This is why it is an important obligation for well-informed citizens to become actively knowledgeable of the issues, who is supporting them, and the methods being used to influence lawmakers by special interests.

Study/Discussion Questions

1. What is the focus of an interest group?

2.. Name three key ingredients to an interest group’s success.

3. How can an interest group affect public policy?

4. What are two techniques utilized by interest groups to mobilize members?

5. Explain what is meant by top-down changes in policy.

6. Which amendment supports the right for interest groups to lobby public policy makers?