12.1: The Family in Cross-Cultural Perspective

- Page ID

- 3431

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Objectives

- Describe the norms that influence the ways in which marriage patterns are organized around the world.

- Describe the societal needs that the institution of the family satisfies.

Universal Generalizations

- The most universal institution is the family.

- In the U.S., the nuclear family is the family form most recognizable to people in the United States.

- In many societies, the nuclear family is embedded in a larger society.

- Some form of family organization exists in all societies.

- No universal norm limits the number of marriage partners an individual may have.

- All families perform similar functions may differ from culture to culture.

- The family acts as the basic economic unit in society.

- The family also provides emotional support for its members.

- In industrialized societies, many of the traditional functions of the family have been taken over by other social institutions.

Guiding Questions

- Should love come before or after two people marry?

- What is a family?

- What functions does the family serve?

- Why don’t all societies use the same marriage and kinship patterns?

- How do industrial and preindustrial societies differ with regards to marriage patterns?

Family Systems and the Functions of the Family

Marriage and family are key structures in most societies. While the two institutions have historically been closely linked in American culture, their connection is becoming more complex. The relationship between marriage and family is an interesting topic of study to sociologists.

Sociologists are interested in the relationship between the institution of marriage and the institution of family because, historically, marriages are what create a family, and families are the most basic social unit upon which society is built. Both marriage and family create status roles that are sanctioned by society.

What is a family? A husband, a wife, and two children—maybe even a pet—has served as the model for the traditional American family for most of the 20th century. But what about families that deviate from this model, such as a single-parent household or a homosexual couple without children? Should they be considered families as well?

The question of what constitutes a family is a prime area of debate in family sociology, as well as in politics and religion. Social conservatives tend to define the family in terms of structure with each family member filling a certain role (like father, mother, or child). Sociologists, on the other hand, tend to define family more in terms of the manner in which members relate to one another than on a strict configuration of status roles. Here, we’ll define family as a socially recognized group (usually joined by blood, marriage, or adoption) that forms an emotional connection and serves as an economic unit of society. Sociologists identify different types of families based on how one enters into them. A family of orientation refers to the family into which a person is born. A family of procreation describes one that is formed through marriage. These distinctions have cultural significance related to issues of lineage.

Drawing on two sociological paradigms, the sociological understanding of what constitutes a family can be explained by symbolic interactionism as well as functionalism. These two theories indicate that families are groups in which participants view themselves as family members and act accordingly. In other words, families are groups in which people come together to form a strong primary group connection, maintaining emotional ties to one another over a long period of time. Such families may include groups of close friends or teammates. In addition, the functionalist perspective views families as groups that perform vital roles for society—both internally (for the family itself) and externally (for society as a whole). Families provide for one another’s physical, emotional, and social well-being. Parents care for and socialize children. Later in life, adult children often care for elderly parents. While interactionism helps us to understand the subjective experience of belonging to a “family,” functionalism illuminates the many purposes of families and their role in the maintenance of a balanced society (Parsons and Bales 1956). We will go into more detail about how these theories apply to family in.

Types of Families and Family Arrangements

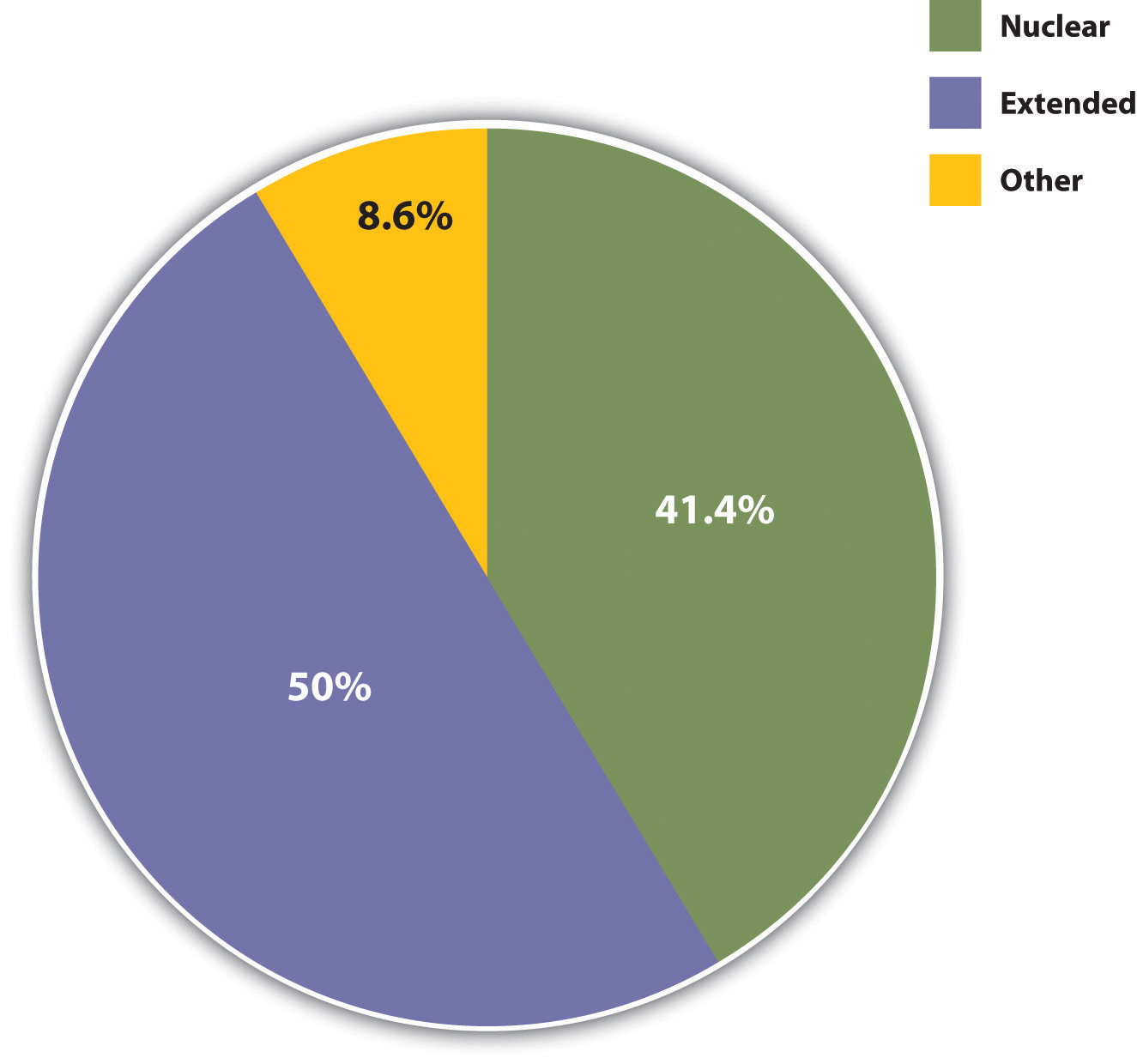

It is important to keep this last statement in mind, because Americans until recently thought of only one type of family when they thought of the family at all, and that is the nuclear family: a married heterosexual couple and their young children living by themselves under one roof. The nuclear family has existed in most societies with which scholars are familiar, and several of the other family types we will discuss stem from a nuclear family. Extended families, for example, which consist of parents, their children, and other relatives, have a nuclear family at their core and were quite common in the preindustrial societies studied by George Murdock (Murdock & White, 1969)Murdock, G. P., & White, D. R. (1969). Standard cross-cultural sample. Ethnology, 8, 329–369. that make up the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (see Figure 15.1.2 "Types of Families in Preindustrial Societies").

Similarly, many one-parent families begin as (two-parent) nuclear families that dissolve upon divorce/separation or, more rarely, the death of one of the parents. In recent decades, one-parent families have become more common in the United States because of divorce and births out of wedlock, but they were actually very common throughout most of human history because many spouses died early in life and because many babies were born out of wedlock.

When Americans think of the family, they also think of a monogamous family. Monogamy refers to a marriage in which one man and one woman are married only to each other. That is certainly the most common type of marriage in the United States and other Western societies, but in some societiespolygamy—the marriage of one person to two or more people at a time—is more common. In the societies where polygamy has prevailed, it has been much more common for one man to have many wives (polygyny) than for one woman to have many husbands (polyandry).

The selection of spouses also differs across societies but also to some degree within societies. The United States and many other societies primarily practice endogamy, in which marriage occurs within one’s own social category or social group: people marry others of the same race, same religion, same social class, and so forth. Endogamy helps reinforce the social status of the two people marrying and to pass it on to any children they may have. Consciously or not, people tend to select spouses and mates (boyfriends or girlfriends) who resemble them not only in race, social class, and other aspects of their social backgrounds but also in appearance. Attractive people marry attractive people, ordinary-looking people marry ordinary-looking people, and those of us in between marry other in-betweeners. This tendency to choose and marry mates who resemble us in all of these ways is called homogamy.

Some societies and individuals within societies practice exogamy, in which marriage occurs across social categories or social groups. Historically exogamy has helped strengthen alliances among villages or even whole nations, when we think of the royalty of Europe, but it can also lead to difficulties. Sometimes these difficulties are humorous, and some of filmdom’s best romantic comedies involve romances between people of very different backgrounds. As Shakespeare’s great tragedy Romeo and Juliet reminds us, however, sometimes exogamous romances and marriages can provoke hostility among friends and relatives of the couple and even among complete strangers. Racial intermarriages, for example, are exogamous marriages, and in the United States they often continue to evoke strong feelings and were even illegal in some states until a 1967 Supreme Court decision (Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1) overturned laws prohibiting them.

Families also differ in how they trace their descent and in how children inherit wealth from their parents. Bilateral descent prevails in the United States and many other Western societies: we consider ourselves related to people on both parents’ sides of the family, and our parents pass along their wealth, meager or ample, to their children. In some societies, though, descent and inheritance are patrilineal (children are thought to be related only to their father’s relatives, and wealth is passed down only to sons), while in others they are matrilineal (children are thought to be related only to their mother’s relatives, and wealth is passed down only to daughters).

Another way in which families differ is in their patterns of authority. In patriarchal families, fathers are the major authority figure in the family (just as in patriarchal societies men have power over women. Patriarchal families and societies have been very common. In matriarchal families, mothers are the family’s major authority figure. Although this type of family exists on an individual basis, no known society has had matriarchal families as its primary family type. In egalitarian families, fathers and mothers share authority equally. Although this type of family has become more common in the United States and other Western societies, patriarchal families are still more common.

Theoretical Perspectives

Sociological views on today’s families generally fall into the functional, conflict, and social interactionist approaches introduced earlier in this book. Let’s review these views, which are summarized in the Theory Snapshot.

Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | The family performs several essential functions for society. It socializes children, it provides emotional and practical support for its members, it helps regulate sexual activity and sexual reproduction, and it provides its members with a social identity. In addition, sudden or far-reaching changes in the family’s structure or processes threaten its stability and weaken society. |

| Conflict | The family contributes to social inequality by reinforcing economic inequality and by reinforcing patriarchy. The family can also be a source of conflict, including physical violence and emotional cruelty, for its own members. |

| Symbolic interactionism | The interaction of family members and intimate couples involves shared understandings of their situations. Wives and husbands have different styles of communication, and social class affects the expectations that spouses have of their marriages and of each other. Romantic love is the common basis for American marriages and dating relationships, but it is much less common in several other contemporary nations. |

Social Functions of the Family

The functional perspective emphasizes that social institutions perform several important functions to help preserve social stability and otherwise keep a society working. A functional understanding of the family thus stresses the ways in which the family as a social institution helps make society possible. As such, the family performs several important functions.

First, the family is the primary unit for socializing children. As previous chapters indicated, no society is possible without adequate socialization of its young. In most societies, the family is the major unit in which socialization happens. Parents, siblings, and, if the family is extended rather than nuclear, other relatives all help socialize children from the time they are born.

Second, the family is ideally a major source of practical and emotional support for its members. It provides them food, clothing, shelter, and other essentials, and it also provides them love, comfort, help in times of emotional distress, and other types of intangible support that we all need.

Third, the family helps regulate sexual activity and sexual reproduction. All societies have norms governing with whom and how often a person should have sex. The family is the major unit for teaching these norms and the major unit through which sexual reproduction occurs. One reason for this is to ensure that infants have adequate emotional and practical care when they are born. The incest taboo that most societies have, which prohibits sex between certain relatives, helps minimize conflict within the family if sex occurred among its members and to establish social ties among different families and thus among society as a whole.

Fourth, the family provides its members with a social identity. Children are born into their parents’ social class, race and ethnicity, religion, and so forth. As we have seen in earlier chapters, social identity is important for our life chances. Some children have advantages throughout life because of the social identity they acquire from their parents, while others face many obstacles because the social class or race/ethnicity into which they are born is at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

Beyond discussing the family’s functions, the functional perspective on the family maintains that sudden or far-reaching changes in conventional family structure and processes threaten the family’s stability and thus that of society. For example, most sociology and marriage-and-family textbooks during the 1950's maintained that the male breadwinner–female homemaker nuclear family was the best arrangement for children, as it provided for a family’s economic and child-rearing needs. Any shift in this arrangement, they warned, would harm children and by extension the family as a social institution and even society itself. Textbooks no longer contain this warning, but many conservative observers continue to worry about the impact on children of working mothers and one-parent families. We return to their concerns shortly.

The Family and Conflict

Conflict theorists agree that the family serves the important functions just listed, but they also point to problems within the family that the functional perspective minimizes or overlooks altogether.

First, the family as a social institution contributes to social inequality in several ways. The social identity it gives to its children does affect their life chances, but it also reinforces a society’s system of stratification. Because families pass along their wealth to their children, and because families differ greatly in the amount of wealth they have, the family helps reinforce existing inequality. As it developed through the centuries, and especially during industrialization, the family also became more and more of a patriarchal unit, helping to ensure men’s status at the top of the social hierarchy.

Second, the family can also be a source of conflict for its own members. Although the functional perspective assumes the family provides its members emotional comfort and support, many families do just the opposite and are far from the harmonious, happy groups depicted in the 1950's television shows. Instead, shout, and use emotional cruelty and physical violence.

Families and Social Interaction

Social interactionist perspectives on the family examine how family members and intimate couples interact on a daily basis and arrive at shared understandings of their situations. Studies grounded in social interactionism give us a keen understanding of how and why families operate the way they do.

Some studies, for example, focus on how husbands and wives communicate and the degree to which they communicate successfully (Tannen, 2001).Tannen, D. (2001). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York, NY: Quill. A classic study by Mirra Komarovsky (1964)Komarovsky, M. (1964). Blue-collar marriage. New York, NY: Random House. found that wives in blue-collar marriages liked to talk with their husbands about problems they were having, while husbands tended to be quiet when problems occurred. Such gender differences seem less common in middle-class families, where men are better educated and more emotionally expressive than their working-class counterparts. Another classic study by Lillian Rubin (1976)Rubin, L. B. (1976). Worlds of pain: Life in the working-class family. New York, NY: Basic Books. found that wives in middle-class families say that ideal husbands are ones who communicate well and share their feelings, while wives in working-class families are more apt to say that ideal husbands are ones who do not drink too much and who go to work every day.

Other studies explore the role played by romantic love in courtship and marriage. Romantic love, the feeling of deep emotional and sexual passion for someone, is the basis for many American marriages and dating relationships, but it is actually uncommon in many parts of the contemporary world today and in many of the societies anthropologists and historians have studied. In these societies, marriages are arranged by parents and other kin for economic reasons or to build alliances, and young people are simply expected to marry whoever is chosen for them. This is the situation today in parts of India, Pakistan, and other developing nations and was the norm for much of the Western world until the late 18th and early 19th centuries (Lystra, 1989).Lystra, K. (1989). Searching the heart: Women, men, and romantic love in nineteenth-century America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Stages of Family Life

The concept of family has changed greatly in recent decades. Historically, it was often thought that most (certainly many) families evolved through a series of predictable stages. Developmental or “stage” theories used to play a prominent role in family sociology (Strong and DeVault 1992). Today, however, these models have been criticized for their linear and conventional assumptions as well as for their failure to capture the diversity of family forms. While reviewing some of these once-popular theories, it is important to identify their strengths and weaknesses

The set of predictable steps and patterns families experience over time is referred to as the family life cycle. One of the first designs of the family life cycle was developed by Paul Glick in 1955. In Glick’s original design, he asserted that most people will grow up, establish families, rear and launch their children, experience an “empty nest” period, and come to the end of their lives. This cycle will then continue with each subsequent generation (Glick 1989). Glick’s colleague, Evelyn Duvall, elaborated on the family life cycle by developing these classic stages of family (Strong and DeVault 1992):

| Stage | Family Type | Children |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marriage Family | Childless |

| 2 | Procreation Family | Children ages 0 to 2.5 |

| 3 | Preschooler Family | Children ages 2.5 to 6 |

| 4 | School-age Family | Children ages 6–13 |

| 5 | Teenage Family | Children ages 13–20 |

| 6 | Launching Family | Children begin to leave home |

| 7 | Empty Nest Family | “Empty nest”; adult children have left home |

The family life cycle was used to explain the different processes that occur in families over time. Sociologists view each stage as having its own structure with different challenges, achievements, and accomplishments that transition the family from one stage to the next. For example, the problems and challenges that a family experiences in Stage 1 as a married couple with no children are likely much different than those experienced in Stage 5 as a married couple with teenagers. The success of a family can be measured by how well they adapt to these challenges and transition into each stage. While sociologists use the family life cycle to study the dynamics of family overtime, consumer and marketing researchers have used it to determine what goods and services families need as they progress through each stage (Murphy and Staples 1979).

As early “stage” theories have been criticized for generalizing family life and not accounting for differences in gender, ethnicity, culture, and lifestyle, less rigid models of the family life cycle have been developed. One example is the family life course, which recognizes the events that occur in the lives of families but views them as parting terms of a fluid course rather than in consecutive stages (Strong and DeVault 1992). This type of model accounts for changes in family development, such as the fact that in today’s society, childbearing does not always occur with marriage. It also sheds light on other shifts in the way family life is practiced. Society’s modern understanding of family rejects rigid “stage” theories and is more accepting of new, fluid models.

The Evolution of Television Families

Whether you grew up watching the Cleavers, the Waltons, the Huxtables, or the Simpsons, most of the iconic families you saw in television sitcoms included a father, a mother, and children cavorting under the same roof while comedy ensued. The 1960s was the height of the suburban American nuclear family on television with shows such as The Donna Reed Show and Father Knows Best. While some shows of this era portrayed single parents (My Three Sons and Bonanza, for instance), the single status almost always resulted from being widowed, not divorced or unwed.

Although family dynamics in real American homes were changing, the expectations for families portrayed on television were not. America’s first reality show, An American Family (which aired on PBS in 1973) chronicled Bill and Pat Loud and their children as a “typical” American family. During the series, the oldest son, Lance, announced to the family that he was gay, and at the series’ conclusion, Bill and Pat decided to divorce. Although the Loud’s union was among the 30 percent of marriages that ended in divorce in 1973, the family was featured on the cover of the March 12 issue of Newsweek with the title “The Broken Family” (Ruoff 2002).

Less traditional family structures in sitcoms gained popularity in the 1980s with shows such as Diff’rent Strokes (a widowed man with two adopted African-American sons) and One Day at a Time (a divorced woman with two teenage daughters). Still, traditional families such as those in Family Ties and The Cosby Show dominated the ratings. The late 1980s and the 1990s saw the introduction of the dysfunctional family. Shows such as Roseanne, Married with Children, and The Simpsons portrayed traditional nuclear families, but in a much less flattering light than those from the 1960s did (Museum of Broadcast Communications 2011).

Over the past 10 years, the nontraditional family has become somewhat of a tradition in television. While most situation comedies focus on single men and women without children, those that do portray families often stray from the classic structure: they include unmarried and divorced parents, adopted children, gay couples, and multigenerational households. Even those that do feature traditional family structures may show less-traditional characters in supporting roles, such as the brothers in the highly rated showsEverybody Loves Raymond and Two and Half Men. Even wildly popular children’s programs as Disney’sHannah Montana and The Suite Life of Zack & Cody feature single parents.

In 2009, ABC premiered an intensely nontraditional family with the broadcast of Modern Family. The show follows an extended family that includes a divorced and remarried father with one stepchild, and his biological adult children—one of who is in a traditional two-parent household, and the other who is a gay man in a committed relationship raising an adopted daughter. While this dynamic may be more complicated than the typical “modern” family, its elements may resonate with many of today’s viewers. “The families on the shows aren't as idealistic, but they remain relatable,” states television critic Maureen Ryan. “The most successful shows, comedies especially, have families that you can look at and see parts of your family in them” (Respers France 2010).

Challenges Families Face

Americans, as a nation, are somewhat divided when it comes to determining what does and what does not constitute a family. In a 2010 survey conducted by professors at the University of Indiana, nearly all participants (99.8 percent) agreed that a husband, wife, and children constitute a family. Ninety-two percent stated that a husband and a wife without children still constitute a family. The numbers drop for less traditional structures: unmarried couples with children (83 percent), unmarried couples without children (39.6 percent), gay male couples with children (64 percent), and gay male couples without children (33 percent) (Powell et al. 2010). This survey revealed that children tend to be the key indicator in establishing “family” status: the percentage of individuals who agreed that unmarried couples and gay couples constitute a family nearly doubled when children were added.

The study also revealed that 60 percent of Americans agreed that if you consider yourself a family, you are a family (a concept that reinforces an interactionist perspective) (Powell 2010). The government, however, is not so flexible in its definition of “family.” The U.S. Census Bureau defines a family as “a group of two people or more (one of whom is the householder) related by birth, marriage, or adoption and residing together” (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). While this structured definition can be used as a means to consistently track family-related patterns over several years, it excludes individuals such as cohabitating unmarried heterosexual and homosexual couples. Legality aside, sociologists would argue that the general concept of family is more diverse and less structured than in years past. Society has given more leeway to the design of a family making room for what works for its members (Jayson 2010).

Family is, indeed, a subjective concept, but it is a fairly objective fact that family (whatever one’s concept of it may be) is very important to Americans. In a 2010 survey by Pew Research Center in Washington, D.C., 76 percent of adults surveyed stated that family is “the most important” element of their life—just one percent said it was “not important” (Pew Research Center 2010). It is also very important to society. President Ronald Regan notably stated, “The family has always been the cornerstone of American society. Our families nurture, preserve, and pass on to each succeeding generation the values we share and cherish, values that are the foundation of our freedoms” (Lee 2009). While the design of the family may have changed in recent years, the fundamentals of emotional closeness and support are still present. Most responders to the Pew survey stated that their family today is at least as close (45 percent) or closer (40 percent) than the family with which they grew up (Pew Research Center 2010).

Alongside the debate surrounding what constitutes a family is the question of what Americans believe constitutes a marriage. Many religious and social conservatives believe that marriage can only exist between man and a woman, citing religious scripture and the basics of human reproduction as support. Social liberals and progressives, on the other hand, believe that marriage can exist between two consenting adults—be they a man and a woman, or a woman and a woman—and that it would be discriminatory to deny such a couple the civil, social, and economic benefits of marriage.

For further information discuss the following article 5 Facts about the American Family http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/04/30/5-facts-about-the-modern-american-family/

Key Takeaways

- The family ideally serves several functions for society. It socializes children, provides practical and emotional support for its members, regulates sexual reproduction, and provides its members with a social identity.

- Reflecting conflict theory’s emphases, the family may also produce several problems. In particular, it may contribute for several reasons to social inequality, and it may subject its members to violence, arguments, and other forms of conflict.

- Social interactionist understandings of the family emphasize how family members interact on a daily basis. In this regard, several studies find that husbands and wives communicate differently in certain ways that sometimes impede effective communication.