1.11: Economic Concepts and the Circular Flow Model

- Page ID

- 6218

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Basic Economic Concepts

Economists carry a set of theories in their heads like a carpenter carries around a toolkit. When they see an economic issue or problem, they go through the theories they know to see if they can find one that fits. Then they use the theory to derive insights about the issue or problem. In economics, theories are expressed as diagrams, graphs, or even as mathematical equations. (Do not worry. In this course, we will mostly use graphs.) Economists do not figure out the answer to the problem first and then draw the graph to illustrate. Instead, they use the graph of the theory to help them figure out the solution.

Although at the basic level, you can sometimes figure out the right answer without applying a model, if you keep studying economics before too long you will run into issues and problems that you will need to graph to solve. Both micro and macroeconomics are explained with theories and models. The most well-known theories are probably those of supply and demand, but you will learn many others.

Universal Generalizations

- Economics provides a foundation for analyzing choices and making decisions.

- Economists believe that economic systems will be able to cope and evolve when necessary.

Guiding Questions

- Why is the free enterprise economy not the same as it was a century ago?

- What do economists predict will happen to economic systems in the future?

Consumers, Goods & Services

Economic products are goods and services that are considered transferable, scarce and useful to individuals, businesses, or governments. When we purchase goods and services, we are consumers. We acquire things or services to satisfy our wants and needs. Because goods and services may be scarce, they will command a price. Consumer goods are products that are intended for use by individuals, such as shoes, backpacks, cars, or computer. While capital goods are items that are manufactured to produce other goods and services, such as a bulldozer used to clear land for homes, school computers for students, or a cash register at a grocery store. Writing paper, food products, and gasoline are considered non-durable goods since they do not last for longer than six months when used regularly. Televisions, refrigerators, or tables are durable goods because they will last three or more years when used on a regular basis.

A service is also considered an economic product because people will pay to have a service performed by someone else. Haircuts, insurance, a visit to the dentist, or banking are all services. The difference between a good and a service is that a good is tangible, it is something that we receive. While a service is something we pay for but it is not tangible.

Value, Utility & Wealth

According to economists, for something to have value, it must be scarce and have utility. Value is defined as an item that has a worth that can be expressed in dollars and cents. Individuals, businesses, and governments determine if a product or service is worth the “value” that is placed on it. If the item is worth more to the consumer than the value it is listed at; then we may decide to purchase the product and trade money for the good or service. This type of economic decision also takes into account the concept of utility. Utility is the usefulness of an item and must provide the purchaser with some satisfaction; otherwise, the purchase would not take place. A product’s utility is determined by the consumer. Some people may find an item more useful than another. One person may enjoy collecting DVDs of movies or attending concerts, while another person may not find those items as useful.

One contradiction in economics is “the paradox of value”. The “paradox of value” is a situation where something should have value because it is useful, such as water, but it, in fact, has little monetary value. On the other hand, diamonds have a high monetary value but have little use and are not essential for survival.

Wealth is the accumulation of all those products that are scarce, tangible and transferable from one person to another. A nation’s wealth is comprised of everything the nation has within its borders. All of the resources, material goods, and skills of a country’s people determine its wealth. When economists evaluate countries and their standard of living, or how well the people live, some nations are therefore considered wealthier than others based on what they have. An example of what may add wealth to a nation would be the amount of fertile land it has for food production.

Economists see the world through a different lens than anthropologists, biologists, classicists, or practitioners of any other discipline. They analyze issues and problems with economic theories that are based on particular assumptions about human behavior, which are different from the assumptions an anthropologist or psychologist might use. A theory is a simplified representation of how two or more variables interact with each other. The purpose of a theory is to take a complex, real-world issue and simplify it down to its essentials. If done well, this enables the analyst to understand the issue and any problems with it. A good theory is simple enough to be understood, while complex enough to capture the key features of the object or situation being studied.

Sometimes economists use the term model instead of theory. Strictly speaking, a theory is a more abstract representation, while a model is a more applied or empirical representation. Models are used to test theories, but for this course, we will use the terms interchangeably.

For example, an architect who is planning an office building will often build a physical model that sits on a tabletop to show how the entire city block will look after the new building is constructed. Companies often build models of their new products, which are more rough and unfinished than the final product will be but can still demonstrate how the new product will work.

Circular Flow Model

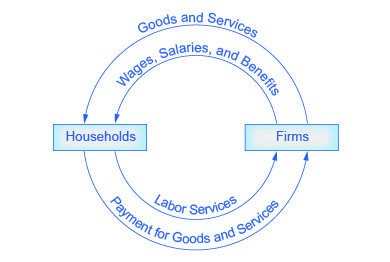

In economics, a good model to start with is the circular flow diagram, shown below. It pictures the economy as consisting of two groups—households and firms—that interact in two markets: the goods and services market in which firms sell and households buy and the labor market in which households sell labor to business firms or other employees.

The Circular Flow Diagram

The circular flow diagram shows how households and firms interact in the goods and services market, and in the labor market. The direction of the arrows shows that in the goods and services market, households receive goods and services and pay firms for them. In the labor market, households provide labor and receive payment from firms through wages, salaries, and benefits.

Of course, in the real world, there are many different markets for goods and services and markets for many different types of labor. The circular flow diagram simplifies this to make the picture easier to grasp. In the diagram, firms produce goods and services, which they sell to households in return for revenues. This is shown in the outer circle and represents the two sides of the product market (for example, the market for goods and services) in which households demand and firms supply. Households sell their labor as workers to firms in return for wages, salaries, and benefits. This is shown in the inner circle and represents the two sides of the labor market in which households supply and firms demand.

This version of the circular flow model is stripped down to the essentials, but it has enough features to explain how the product and labor markets work in the economy. We could easily add details to this basic model if we wanted to introduce more real-world elements, like financial markets, governments, and interactions with the rest of the globe (imports and exports).

Video: Circular Flow of Income and Expenditures

Circular Flow of Economic Activity

The circular flow of economic activity helps to generate wealth in a country. The features of the product markets, businesses, individuals and factor markets, allows buyers and sellers to exchange money for products or products for money. Markets may be local, regional, national or international. In the last several years the internet has helped to facilitate the idea of a truly global market. Businesses and individuals can locate and exchange goods and services all with the click of a mouse.

Factor markets are places where productive resources are bought and sold. This is where workers sell their labor and entrepreneurs look for labor. This is also where land is bought, sold or rented by businesses and where banks lend capital or money. The factors market is the place where the four factors of production (land, labor, capital, entrepreneurs) come together.

Businesses and individuals spend money in the product market where they purchase goods and services. Therefore the money that individuals receive from working in the factor market (at their job) is then spent in the product markets acquiring goods and services. Then a business uses the money to hire more workers, produce more goods, and increase their business output. Thus the cycle continues, and if the business cycle is doing well, then the added result will be that the economy will grow.

Economic growth will occur if the country’s output of goods and services increases over time. The circular flow diagram will continue to expand, and more and more items will be for sale as long as people have jobs (participate as labor) and continue to spend their money on those products. If people lose their jobs or are fearful about the future, they will not spend money, which would hurt the circular flow of economic activity, and the overall economy will contract.

Everyone benefits if the economy is expanding. Productivity can increase if resources are used efficiently, and the factors of production are skillfully applied. If a company hires workers who are proficient in their jobs, then the division of labor and specialization of the workforce can, in fact, increase the productivity of the company. One of the best ways to improve the workforce is by investing in human capital, or the education and skills of the laborers. The better qualified, competent, and motivated a workforce is, the more productive it can be. Those workers who are skilled in their occupations can impact the performance of the business and the life of the employees. Workers with more education and skills have higher earning potential over their lifetimes and contribute to the economy by participating in the circular flow of economic activity.

Our economy relies on everyone doing their part in the circular flow of economic activity. Events that occur locally, or nationally, impact the rest of the consumers and producers in this country. Once again we realize why the concept of economics is vital to everyone, and how our participation in the economy can impact others.

Financing Higher Education

On November 8, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed The Higher Education Act of 1965 into law. With a stroke of the pen, he implemented what we know as the financial aid, work-study, and student loan programs to help Americans pay for a college education. In his remarks, the President said:

Here the seeds were planted from which grew my firm conviction that for the individual, education is the path to achievement and fulfillment; for the Nation, it is a path to a society that is not only free but civilized; and for the world, it is the path to peace—for it is education that places reason over force.

President Lyndon B. Johnson

This Act, he said, "is responsible for funding higher education for millions of Americans. It is the embodiment of the United States’ investment in ‘human capital’." Since the Act was first signed into law, it has been renewed several times.

The purpose of The Higher Education Act of 1965 was to build the country’s human capital by creating educational opportunity for millions of Americans. The three criteria used to judge eligibility are income, full-time or part-time attendance, and the cost of the institution. According to the 2011–2012 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:12), in the 2011–2012 school year, over 70% of all full-time college students received some form of federal financial aid; 47% received grants, and another 55% received federal government student loans. The budget to support financial aid has increased not only because of increased enrollment but also because of increased tuition and fees for higher education. These increases are currently being questioned. The President and Congress are charged with balancing fiscal responsibility and significant government-financed expenditures like investing in human capital.

Video: The Circular Flow Matrix

View the video below by economics teacher Jacob Clifford for another explanation of the circular flow model.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.

Self Check Questions

- What is an example of a problem in the world today, not mentioned in this chapter, that has an economic component?

- Are households primarily buyers or sellers in the goods and services market? In the labor market?

- Are firms primarily buyers or sellers in the goods and services market? In the labor market?

- Discuss the relationship between scarcity, value, utility, and wealth.

- Explain why productivity is vital to economic growth.

- In what ways do businesses and households both supply and demand in the circular flow model?

Application:

Suppose, as an economist, you are asked to analyze an issue, unlike anything you have ever done before. Also, suppose you do not have a specific model for analyzing that issue. What should you do? Hint: What would a carpenter do in a similar situation?