6.26: Water Cycle

- Page ID

- 1490

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Where does the water come from that is needed by your cells?

Unlike energy, matter is not lost as it passes through an ecosystem. Instead, matter, including water, is recycled. This recycling involves specific interactions between the biotic and abiotic factors in an ecosystem. Chances are, the water you drank this morning has been around for millions of years, or more.

The Water Cycle

The chemical elements and water that are needed by organisms continuously recycle in ecosystems. They pass through biotic and abiotic components of the biosphere. That’s why their cycles are called biogeochemical cycles. For example, a chemical might move from organisms (bio) to the atmosphere or ocean (geo) and back to organisms again. Elements or water may be held for various periods of time in different parts of a cycle.

- Part of a cycle that holds an element or water for a short period of time is called an exchange pool. For example, the atmosphere is an exchange pool for water. It usually holds water (in the form of water vapor) for just a few days.

- Part of a cycle that holds an element or water for a long period of time is called a reservoir. The ocean is a reservoir for water. The deep ocean may hold water for thousands of years.

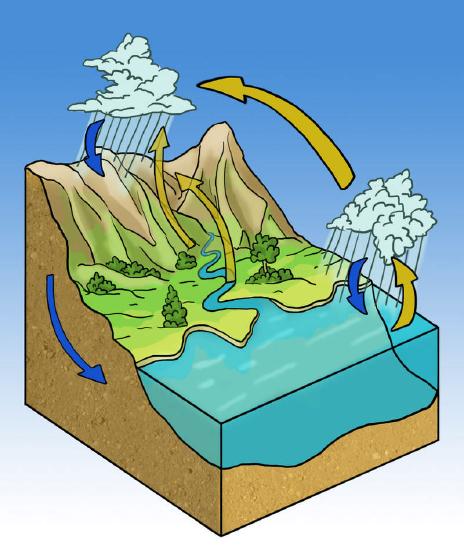

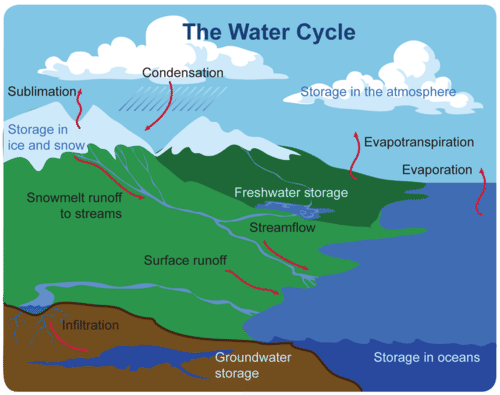

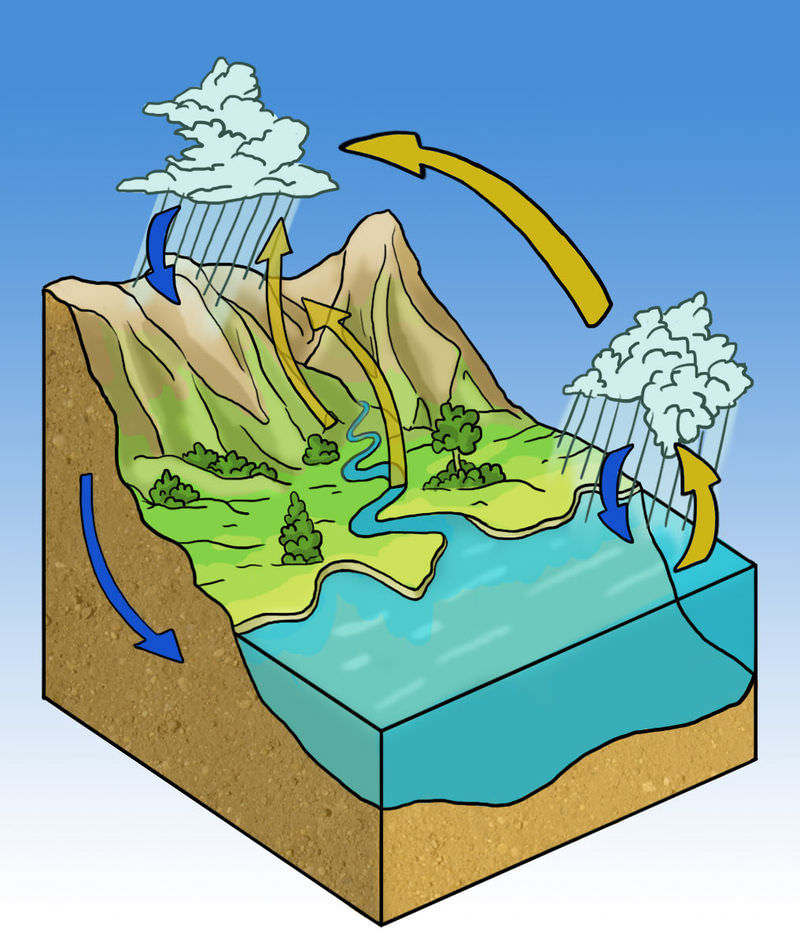

Water on Earth is billions of years old. However, individual water molecules keep moving through the water cycle. The water cycle is a global cycle. It takes place on, above, and below Earth’s surface, as shown in Figure below.

Like other biogeochemical cycles, there is no beginning or end to the water cycle. It just keeps repeating.

Like other biogeochemical cycles, there is no beginning or end to the water cycle. It just keeps repeating.During the water cycle, water occurs in three different states: gas (water vapor), liquid (water), and solid (ice). Many processes are involved as water changes state in the water cycle.

Evaporation, Sublimation, and Transpiration

Water changes to a gas by three different processes:

- Evaporation occurs when water on the surface changes to water vapor. The sun heats the water and gives water molecules enough energy to escape into the atmosphere.

- Sublimation occurs when ice and snow change directly to water vapor. This also happens because of heat from the sun.

- Transpiration occurs when plants release water vapor through leaf pores called stomata (see Figure below).

Plant leaves have many tiny stomata. They release water vapor into the air.

Plant leaves have many tiny stomata. They release water vapor into the air.Condensation and Precipitation

Rising air currents carry water vapor into the atmosphere. As the water vapor rises in the atmosphere, it cools and condenses. Condensation is the process in which water vapor changes to tiny droplets of liquid water. The water droplets may form clouds. If the droplets get big enough, they fall as precipitation—rain, snow, sleet, hail, or freezing rain. Most precipitation falls into the ocean. Eventually, this water evaporates again and repeats the water cycle. Some frozen precipitation becomes part of ice caps and glaciers. These masses of ice can store frozen water for hundreds of years or longer.

Groundwater and Runoff

Precipitation that falls on land may flow over the surface of the ground. This water is called runoff. It may eventually flow into a body of water. Some precipitation that falls on land may soak into the ground, becoming groundwater. Groundwater may seep out of the ground at a spring or into a body of water such as the ocean. Some groundwater may be taken up by plant roots. Some may flow deeper underground to an aquifer. This is an underground layer of rock that stores water, sometimes for thousands of years.

Science Friday: Forecasting the Meltdown: The Aerial Snow Observatory

75% of Southern California's water supply comes from the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range. This video by Science Friday explains how NASA uses the Airborne Snow Observatory that uses specialized instrumentation to carefully measure the water content.

Summary

- Chemical elements and water are recycled through biogeochemical cycles. The cycles include both biotic and abiotic parts of ecosystems.

- The water cycle takes place on, above, and below Earth’s surface. In the cycle, water occurs as water vapor, liquid water, and ice. Many processes are involved as water changes state in the cycle.

- The atmosphere is an exchange pool for water. Ice masses, aquifers, and the deep ocean are water reservoirs.

Review

- What is a biogeochemical cycle? Name an example.

- Identify and define two processes by which water naturally changes from a solid or liquid to a gas.

- Define exchange pool and reservoir, and identify an example of each in the water cycle.

- Assume you are a molecule of water. Describe one way you could go through the water cycle, starting as water vapor in the atmosphere.

| Image | Reference | Attributions |

|

[Figure 1] | Credit: Image copyright mosista, 2014;Stomata: Dartmouth Electron Microscope Facility; Leaf: Jon Sullivan Source: http://www.shutterstock.com ; Stomata: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomato_leaf_stomate_1-color.jpg ; Leaf: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leaf_1_web.jpg License: Public Domain |

|

[Figure 2] | Credit: Mariana Ruiz Villarreal (LadyofHats) for CK-12 Foundation;Top 3 images courtesy of NOAA; bottom left image by CK-12 Foundation - Christopher Auyeung; bottom right courtesy of National Severe Storms Laboratory;Amy Goldstein;Stomata: Dartmouth Electron Microscope Facility; Leaf: Jon Sullivan Source: CK-12 Foundation ; Top 3 images: www.srh.noaa.gov/jetstream//synoptic/precip.htm ; Bottom right image: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Granizo.jpg ; http://www.flickr.com/photos/amylovesyah/3945525048/ ; Stomata: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomato_leaf_stomate_1-color.jpg ; Leaf: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leaf_1_web.jpg License: CC BY-NC 3.0; CC BY-NC 3.0; Top 3 images and bottom right images: Public Domain; CC BY 2.0; Public Domain |

|

[Figure 3] | Credit: Stomata: Dartmouth Electron Microscope Facility; Leaf: Jon Sullivan;Top 3 images courtesy of NOAA; bottom left image by CK-12 Foundation - Christopher Auyeung; bottom right courtesy of National Severe Storms Laboratory;Amy Goldstein Source: Stomata: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomato_leaf_stomate_1-color.jpg ; Leaf: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leaf_1_web.jpg ; Top 3 images: www.srh.noaa.gov/jetstream//synoptic/precip.htm ; Bottom right image: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Granizo.jpg ; http://www.flickr.com/photos/amylovesyah/3945525048/ License: Public Domain; CC BY-NC 3.0; (Top 3 and bottom right images) Public Domain; CC BY 2.0 |