9.5: Roots

- Page ID

- 12228

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

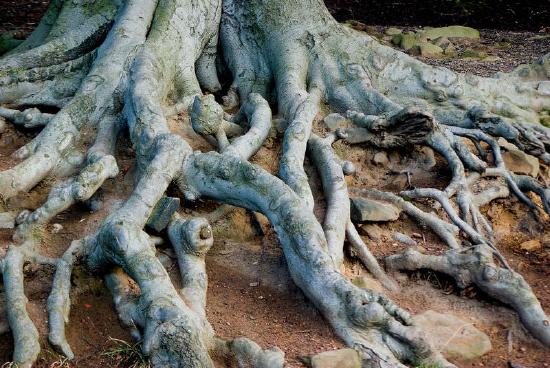

Now those are some serious roots. But what exactly are roots?

There are taproots and fibrous roots, primary roots and secondary roots. And they always seem to know which way to grow. Roots are very special plant organs. How and why?

Roots

Plants have specialized organs that help them survive and reproduce in a great diversity of habitats. Major organs of most plants include roots, stems, and leaves.

Roots are important organs in all vascular plants. Most vascular plants have two types of roots: primary roots that grow downward and secondary roots that branch out to the side. Together, all the roots of a plant make up a root system.

Root Systems

There are two basic types of root systems in plants: taproot systems and fibrous root systems. Both are illustrated in Figure below.

- Taproot systems feature a single, thick primary root, called the taproot, with smaller secondary roots growing out from the sides. The taproot may penetrate as many as 60 meters (almost 200 feet) below the ground surface. It can plumb very deep water sources and store a lot of food to help the plant survive drought and other environmental extremes. The taproot also anchors the plant very securely in the ground.

- Fibrous root systems have many small branching roots, called fibrous roots, but no large primary root. The huge number of threadlike roots increases the surface area for absorption of water and minerals, but fibrous roots anchor the plant less securely.

Dandelions have taproot systems; grasses have fibrous root systems.

Dandelions have taproot systems; grasses have fibrous root systems.Root Structures and Functions

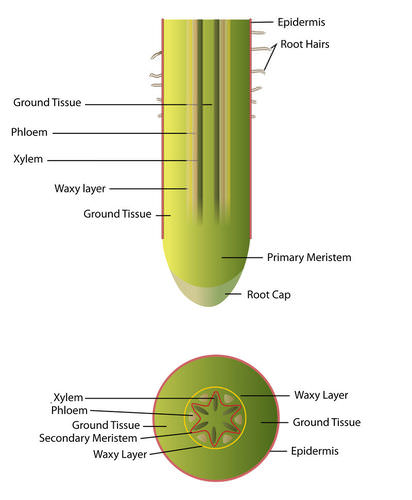

As shown in Figure below, the tip of a root is called the root cap. It consists of specialized cells that help regulate primary growth of the root at the tip. Above the root cap is primary meristem, where growth in length occurs.

A root is a complex organ consisting of several types of tissue. What is the function of each tissue type?

A root is a complex organ consisting of several types of tissue. What is the function of each tissue type?Above the meristem, the rest of the root is covered with a single layer of epidermal cells. These cells may have root hairs that increase the surface area for the absorption of water and minerals from the soil. Beneath the epidermis is ground tissue, which may be filled with stored starch. Bundles of vascular tissues form the center of the root. Waxy layers waterproof the vascular tissues so they don’t leak, making them more efficient at carrying fluids. Secondary meristem is located within and around the vascular tissues. This is where growth in thickness occurs.

The structure of roots helps them perform their primary functions. What do roots do? They have three major jobs: absorbing water and minerals, anchoring and supporting the plant, and storing food.

- Absorbing water and minerals: Thin-walled epidermal cells and root hairs are well suited to absorb water and dissolved minerals from the soil. The roots of many plants also have a mycorrhizal relationship with fungi for greater absorption.

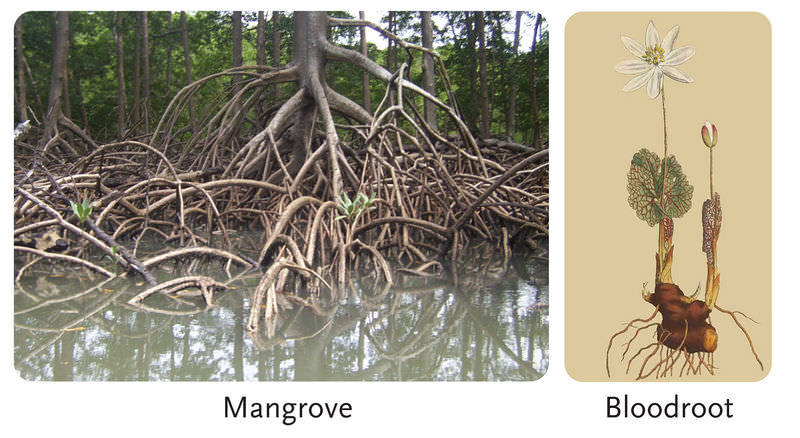

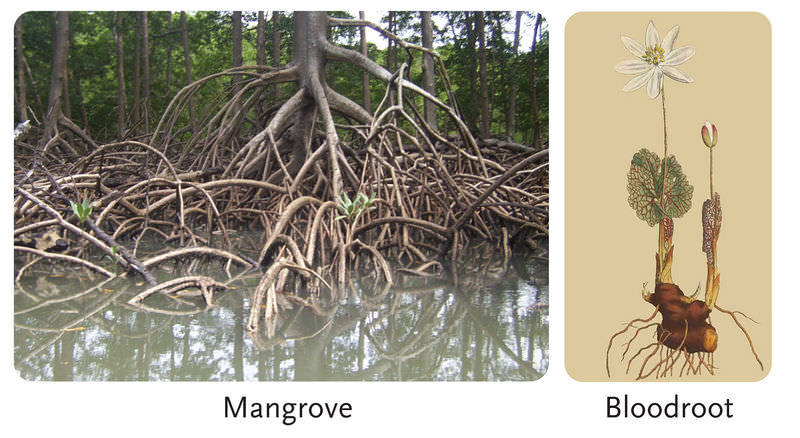

- Anchoring and supporting the plant: Root systems help anchor plants to the ground, allowing plants to grow tall without toppling over. A tough covering may replace the epidermis in older roots, making them ropelike and even stronger. As shown in Figure below, some roots have unusual specializations for anchoring plants.

- Storing food: In many plants, ground tissues in roots store food produced by the leaves during photosynthesis. The bloodroot shown in Figure below stores food in its roots over the winter.

Mangrove roots are like stilts, allowing mangrove trees to rise high above the water. The trunk and leaves are above water even at high tide. A bloodroot plant uses food stored over the winter to grow flowers in the early spring.

Mangrove roots are like stilts, allowing mangrove trees to rise high above the water. The trunk and leaves are above water even at high tide. A bloodroot plant uses food stored over the winter to grow flowers in the early spring.Root Growth

Roots have primary and secondary meristems for growth in length and width. As roots grow longer, they always grow down into the ground. Even if you turn a plant upside down, its roots will try to grow downward. How do roots “know” which way to grow? How can they tell down from up? Specialized cells in root caps are able to detect gravity. The cells direct meristem in the tips of roots to grow downward toward the center of Earth. This is generally adaptive for land plants. Can you explain why?

As roots grow thicker, they can’t absorb water and minerals as well. However, they may be even better at transporting fluids, anchoring the plant, and storing food (see Figure below).

Secondary growth of sweet potato roots provides more space to store food. Roots store sugar from photosynthesis as starch. What other starchy roots do people eat?

Secondary growth of sweet potato roots provides more space to store food. Roots store sugar from photosynthesis as starch. What other starchy roots do people eat?Science Friday: Plants in Space!

For humans to travel to the Moon and Mars, astronauts will need to understand how to grow plants in extreme climates in order to help them stay alive. In this video by Science Friday, Dr. Anna-Lisa Paul and Dr. Robert J. Ferl send weeds to space to study their behavior on a molecular level.

Summary

- Roots absorb water and minerals and transport them to stems. They also anchor and support a plant, and store food.

- A root system consists of primary and secondary roots.

- Each root is made of dermal, ground, and vascular tissues.

- Roots grow in length and width from primary and secondary meristem.

Review

- What are root hairs? What is their role?

- Identify three major functions of roots.

- Contrast a taproot system with a fibrous root system.

- Explain how roots “know” which way to grow.

| Image | Reference | Attributions |

|

[Figure 1] | Credit: Joanne Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/cuyahogajco/6251221084/ License: CC BY 2.0 |

|

[Figure 2] | Credit: Taproot: Robbie Sproule; Fibrous: Image copyright Nata-Lia, 2014 Source: Taproot: http://www.flickr.com/photos/robbie1/501522313/ ; Fibrous: http://www.shutterstock.com License: Taproot: CC BY; Fibrous: License from Shutterstock |

|

[Figure 3] | Credit: CK-12 Foundation Source: CK-12 Foundation License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |

|

[Figure 4] | Credit: Mangrove: Cesar Paes Barreto; Bloodroot: William Curtis Source: Mangrove: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roots_by_cesarpb.jpg ; Bloodroot: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bloodwort_-_Project_Gutenberg_eText_19123.jpg License: Mangrove: The copyright holder of this work allows anyone to use it for any purpose including unrestricted redistribution, commercial use, and modification; Bloodroot: Public Domain |

|

[Figure 5] | Credit: Joanne Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/cuyahogajco/6251221084/ License: CC BY 2.0 |