3.9: Property Matters

- Page ID

- 1695

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Property Matters

Business owners have the right to own, use, and dispose of property, yet they also have the responsibility to follow government regulations. The most common form of land-use regulation is zoning. Since New York City adopted the first zoning ordinance in 1916, zoning regulations have been adopted by virtually every major urban area in the United States.

Universal Generalizations

- Land use and zoning involve the regulation of the use and development of real estate.

- Zoning regulations and restrictions are used by municipalities to control and direct the development of property within their borders.

Guiding Questions

- What are the costs and benefits of owning property and/or a business?

- How do financial institutions facilitate business operations?

- What types of governmental restrictions are made on the use of business and property?

- What ordinance and regulations apply to the establishment and operation of sole proprietorships, partnerships, and corporations?

What are Zoning Regulations?

The basic purpose and function of zoning is to divide a municipality into residential, commercial, and industrial districts (or zones), that are for the most part separate from one another, with the use of property within each district being reasonably uniform. Within these three main types of districts there will generally be additional restrictions that can be quite detailed -- including the following:

- Specific requirements as to the type of buildings allowed

- Location of utility lines

- Restrictions on accessory buildings, building setbacks from the streets and other boundaries

- Size and height of buildings

- Number of rooms

These restrictions may also cover the frontage of lots; minimum lot area; front, rear, and side yards; off-street parking; the number of buildings on a lot; and the number of dwelling units in a certain area. Regulations may restrict areas to single-family homes or to multi-family dwellings or townhouses. In areas of historic or cultural significance, zoning regulations may require that certain features be preserved.

Regulation of Development

Land-use regulation is not restricted to controlling existing buildings and uses; in large part, it is designed to guide future development. Municipalities commonly follow a planning process that ultimately results in a master plan, and in some states the creation of an official map for a municipality. The master plan is then put into effect by ordinances controlling zoning, regulation of subdivision developments, street plans, plans for public facilities, and building regulations. Future developers must plan their subdivisions in accordance with the official map or plan.

In recent years, an increasing emphasis has been placed on regional and statewide planning. Recognizing that the actions of one municipality will strongly affect neighboring cities, occasionally in conflicting and contradictory ways, these planning initiatives allow the creation of a regional plan that offers one comprehensive vision and one set of regulations.

Limits on Zoning Regulation

Because land-use and zoning regulations restrict the rights of owners to use their property as they otherwise could (and often want to), they are at times controversial. Additionally, the scope and limits of governments' ability to regulate land use is hard to define with specificity. Courts have held that a zoning regulation is permissible if it is reasonable and not arbitrary; if it bears a reasonable and substantial relation to the public health, safety, comfort, morals, and general welfare; and if the means employed are reasonably necessary for the accomplishment of its purpose.

Given the subjective nature of these factors, there is obviously a lot of room for disagreement, and on occasion litigation. One extremely difficult question presented in this area of law is how far land-use regulations may go without running into the constitutional prohibition against taking private property for public use without just compensation.

Challenges to Zoning Regulations

There are numerous other restrictions on the power of government to regulate land use, any of which may provide a basis upon which such regulations can be challenged. Zoning ordinances must be reasonable based on all factors involved, such as the need of the municipality; the purpose of the restriction; the location, size, and physical characteristics of the land; the character of the neighborhood; and its effect on the value of the property involved. The rationale behind zoning is that it promotes the good of the entire community in accordance with a comprehensive plan.

Spot zoning of individual parcels of property in a manner different from that of surrounding property, primarily for the private interests of the owner of the property so zoned, is subject to challenge unless there is a reasonable basis for distinguishing the parcel from surrounding parcels. Restrictions based solely on race or occupancy of property are not permitted, and a classification that discriminates against a racial or religious group can only be upheld if the state demonstrates an overwhelming interest that can be served no other way.

In many jurisdictions, statutes have created boards of zoning appeals to handle these issues. These are quasi-judicial bodies that can conduct hearings with sworn testimony by witnesses and whose decisions are subject to court review. Given both the complexity of zoning law and the specialized nature of zoning appeals boards, an owner who contests a zoning requirement is ill-advised to try to argue his or her case without legal assistance.

Non-Government Restrictions: Restrictive Covenants and Easements

Not all land use restrictions are created by governments. Land developers may also incorporate restrictions in their developments, most commonly through the use of restrictive covenants and easements:

Restrictive covenants are provisions in a deed limiting the use of the property and prohibiting certain uses. Restrictive covenants are typically used by land developers to establish minimum house sizes, setback lines, and aesthetic requirements thought to enhance the neighborhood.

Easements are rights to use the property of another for particular purposes. Easements also are now used for public objectives, such as the preservation of open space and conservation. For example, an easement might preclude someone from building on a parcel of land, which leaves the property open and thereby preserves an open green space for the benefit of the public as a whole.

Development Plan Threatens El Paso Neighborhood

Local Preservationists are fighting to save El Paso's Barrio Duranguito from redevelopment.

Local Preservationists are fighting to save El Paso's Barrio Duranguito from redevelopment.In each Transitions section of Preservation magazine, we highlight places of local and national importance that have recently been restored, are currently threatened, have been saved from demolition or neglect, or have been lost. Here's one from Spring 2017.

The longest-occupied area in El Paso, Texas, is facing a potential threat from an arena development plan put forward by the city.

Barrio Duranguito, located within the larger Union Plaza neighborhood, was established by the early 1900s by migrants from Durango, Mexico. (The oldest existing structure dates to 1879.) The $180 million arena project was proposed in 2012, and in 2016 the city council approved its location in a section of downtown that encompasses part of Duranguito, allowing the city to use eminent domain if necessary. An estimated 150 people could face displacement, sparking an outcry from preservationists and community residents.

In December of 2016, the city council voted to rule out that location, sparing the neighborhood, but in early January it released plans for a new feasibility study that once again considered the area viable. The attraction of Duranguito is its proximity to the convention and performing arts center El Paso Live; building the new arena within 1,000 feet of it would allow the city government to take advantage of $25 million in state tax incentives for new hotels over several years.

The grassroots organization Paso del Sur has been vocal about preserving Duranguito, circulating a petition and organizing protests. As of press time, the feasibility study had been nixed, but Duranguito/Union Plaza was still the city’s preferred site for the arena project.

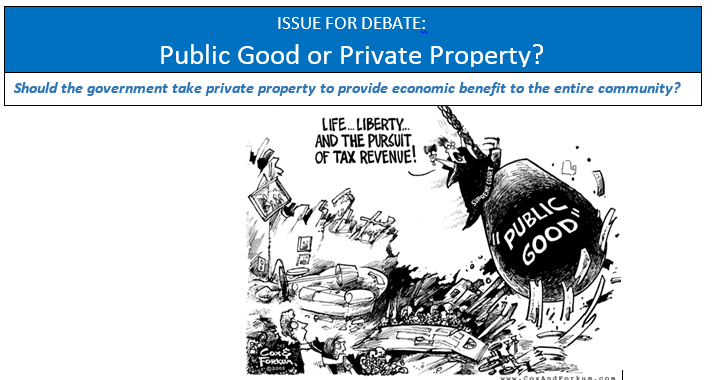

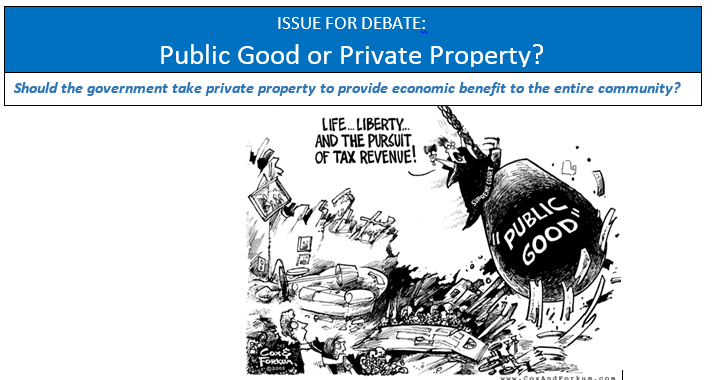

Under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the people are guaranteed, “Life, liberty, and property,” and the protection that no person’s property can be taken by the government for public use without just compensation. The Fifth Amendment does not specifically define the terms “public use” or “just compensation.” The courts have traditionally upheld the rights of the national and state governments to exercise eminent domain, which is the power of the government to take private property for public use, with the presumption that the property is to serve “the public good." This means it should provide an essential benefit to the entire community. In exchange, the rule of eminent domain requires the government to pay property owners a fair price for the land. When the rights of property owners and the power of the government are at odds, conflicts will naturally arise.

Questions for Consideration

- Who should decide what is in “the greater public good?”

- Whose rights are more important – the government or the people?

- Who determines what constitutes a fair price?

A Practical Example: Kelo v. the City of New London (2005)

Video: The Story of Susette Kelo

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TAgEgjoycQ4

Attribution: Institute for Justice ij.org/freedomflix/category/35/177?subcatid=2

In this case, the city of New London, Connecticut condemned the property of Susette Kelo and her neighbors in order to provide for a “comprehensive redevelopment plan” involving a privately funded project. The private developer was ultimately unable to obtain the financing he needed, and the land was turned into a temporary dump. Kelo sued the city of New London claiming her land was taken illegally as it was not used for the “public good.” In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court held that the general benefits a community enjoyed from economic growth qualified private redevelopment plans as permissible “public use” under the “Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment.” Recently, this decision has been used to support the condemnation of public property for a number of private projects.

| Allowing for the Use of Eminent Domain | Limiting the use of Eminent Domain |

| Should economic benefits of private development projects be considered public use under the Fifth Amendment? In Kelo v. City of New London (2005), the Supreme Court stated that condemning private residences in order to build a redevelopment project (including shops, restaurants, offices, and a hotel) qualified as “public use.” Since the Fifth Amendment does not provide a specific definition of public use, the Court held that a “broader and more natural interpretation of public use” was sufficient. The court, instead, held “the broader and more natural interpretation of public use as ‘public purpose.’” The reasoning of the Court was that because it was intended to benefit the economic development of the community, the redevelopment plan fit the definition of public use. | Following the Kelo decision, many Americans feared that this ruling gave local government too much authority for the seizure of private property. Many states have passed legislation intended to restrict the use of eminent domain and around four months following the Kelo decision, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Private Property Rights Protection Act. This law specified that public funds would be withheld from state and local governments who chose to exercise eminent domain over property intended for private economic development purposes. The bill does make allowances for public projects such as the building of roads and hospitals and in cases involving abandoned private property. |

To read an article on how eminent domain issues are affecting plans to build a border wall read follow this link: Trump’s wall needs private property. But some Texans won’t give up their land without a fight.

Answer the self check questions below to monitor your understanding of the concepts in this section.

Self Check Questions

- What are the disadvantages of government regulations on a property?

- What are the advantages of government regulations on a property?

- What types of governmental restrictions are made on the use of business and property?

Learning Extensions

Writing Assignment

If you lived in a community that could benefit from the seizure of private property in order to provide economic benefits such as jobs, shops, restaurants, and other businesses would you be willing to allow your property to be seized through eminent domain if it went to "the public good"? Why/why not?

What if it were another neighborhood in your community and it meant you might benefit from the new jobs created? How would you feel then?

Classroom Debate

Get into groups and conduct more research about the Kelo case and others that have followed it. After conducting your research, conduct a classroom debate about the positive and negative effects of the use of eminent domain for private projects.

CC BY – John M. Seymour (Author); based on case study in Fraga, Luis; The United States Government: Principles in Practice; © 2000, Holt McDougal Publishers; Pg. 13.

| Image | Reference | Attributions |

|

[Figure 1] | Credit: Katherine Flynn Source: https://savingplaces.org/stories/development-plan-threatens-el-paso-neighborhood#.Wx6ot4gvyCg License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |

|

[Figure 2] | Credit: Labeled as CC Fair Use by Google Images accessed 12/29/2014;Katherine Flynn Source: http://www.planetizen.com/files/eminent-domain-cartoon.gif ; https://savingplaces.org/stories/development-plan-threatens-el-paso-neighborhood#.Wx6ot4gvyCg License: CC BY-NC 3.0 |