2.16: Parallelogram Proofs

- Page ID

- 7188

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Apply theorems to show if a quadrilateral has two pairs of parallel sides.

Quadrilaterals that are Parallelograms

Recall that a parallelogram is a quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides. Even if a quadrilateral is not marked with having two pairs of sides, it still might be a parallelogram. The following is a list of theorems that will help you decide if a quadrilateral is a parallelogram or not.

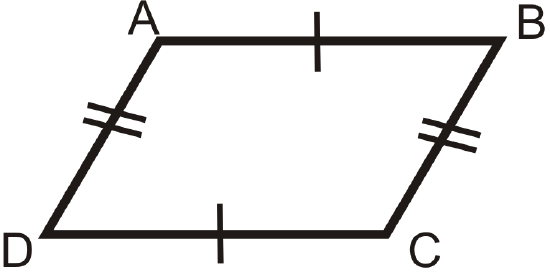

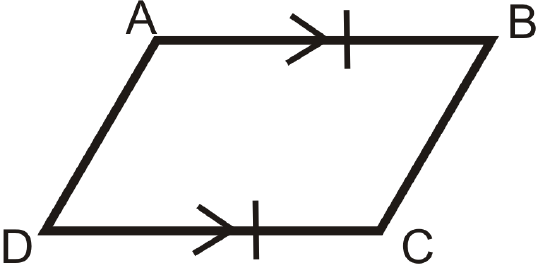

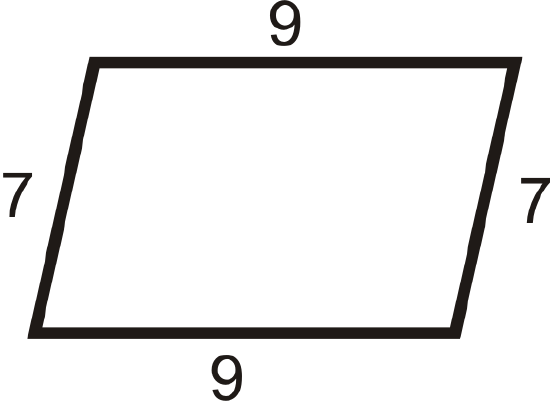

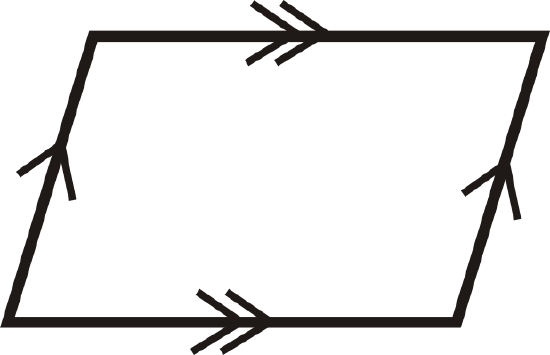

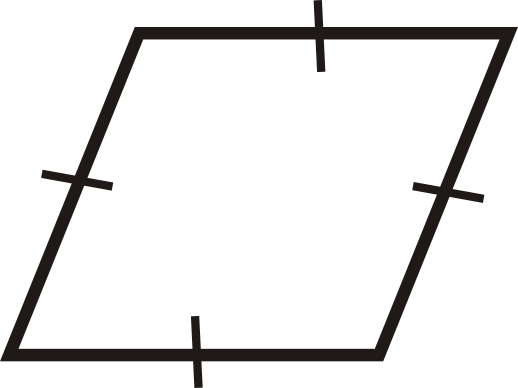

1. Opposite Sides Theorem Converse: If both pairs of opposite sides of a quadrilateral are congruent, then the figure is a parallelogram.

If

then

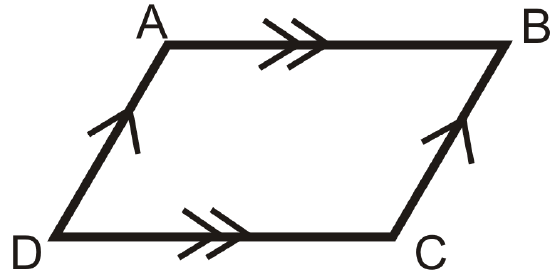

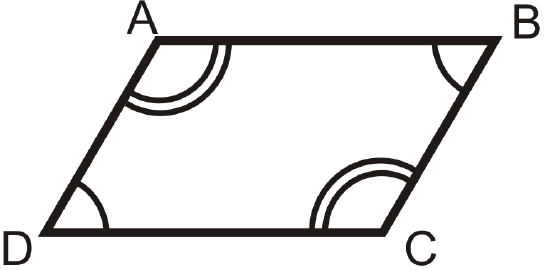

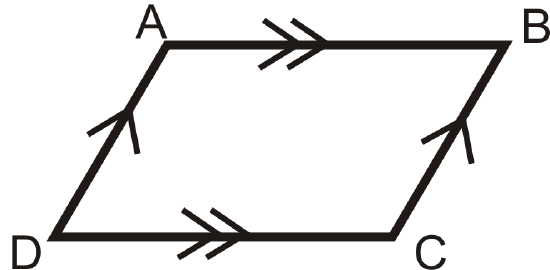

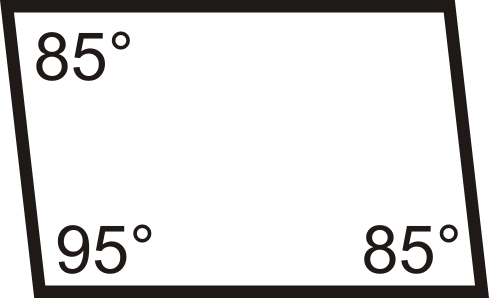

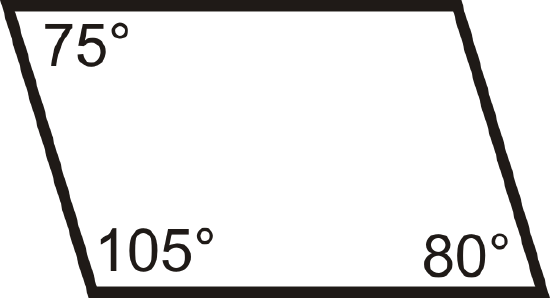

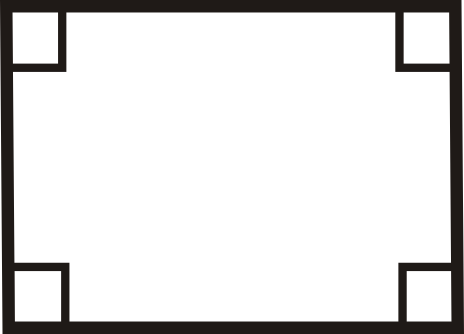

2. Opposite Angles Theorem Converse: If both pairs of opposite angles of a quadrilateral are congruent, then the figure is a parallelogram.

If

then

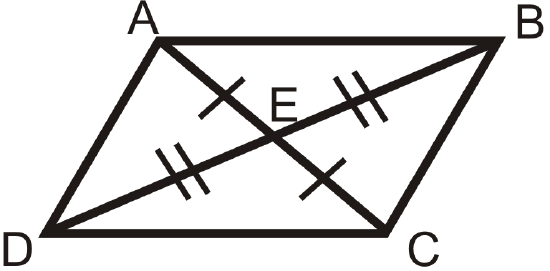

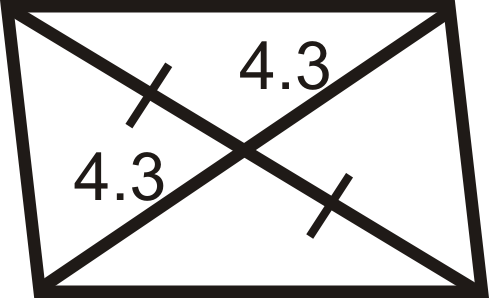

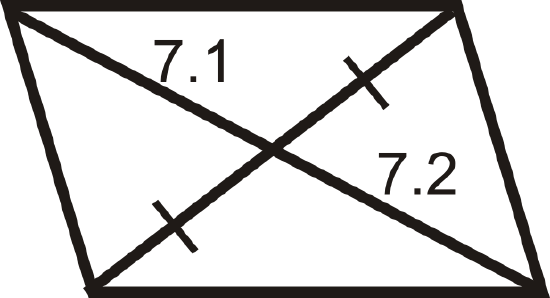

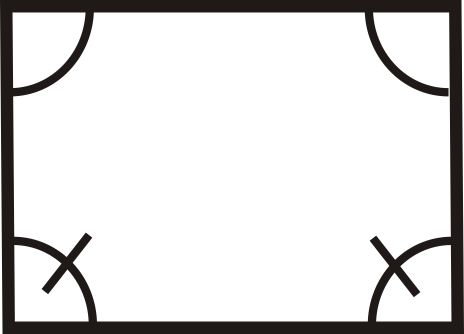

3. Parallelogram Diagonals Theorem Converse: If the diagonals of a quadrilateral bisect each other, then the figure is a parallelogram.

If

then

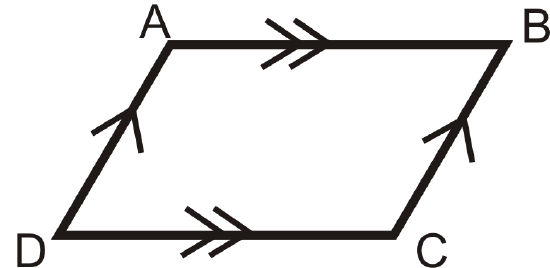

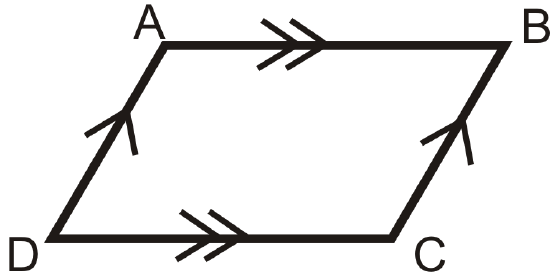

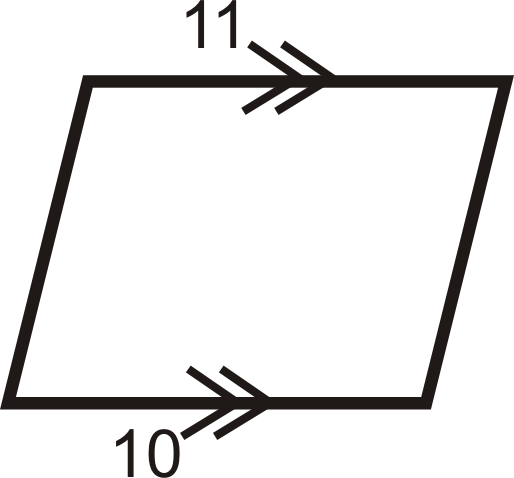

4. Parallel Congruent Sides Theorem: If a quadrilateral has one set of parallel lines that are also congruent, then it is a parallelogram.

If

then

You can use any of the above theorems to help show that a quadrilateral is a parallelogram. If you are working in the x−y plane, you might need to know the formulas shown below to help you use the theorems.

- The Slope Formula, \(\dfrac{y_2−y_1}{x_2−x_1}\). (Remember that if slopes are the same then lines are parallel).

- The Distance Formula, \(\sqrt{(x_2−x_1)^2+(y_2−y_1)^2}\). (This will help you to show that two sides are congruent).

- The Midpoint Formula, \( ( \dfrac{x_1+x_2}{2}, \dfrac{y_1+y_2}{2} )\). (If the midpoints of the diagonals are the same then the diagonals bisect each other).

What if you were given four pairs of coordinates that form a quadrilateral? How could you determine if that quadrilateral is a parallelogram?

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

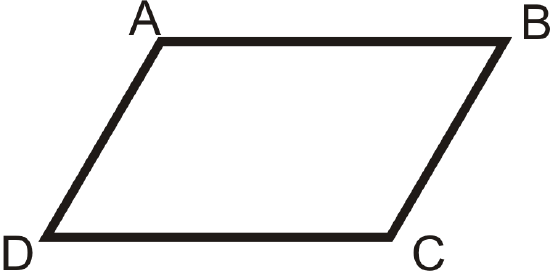

Prove the Parallel Congruent Sides Theorem.

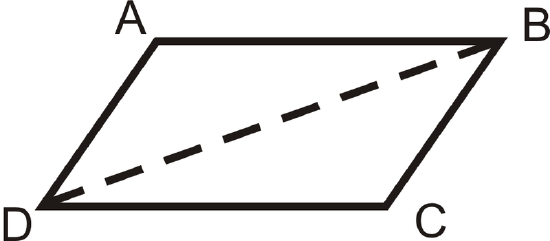

Given: \(\overline{AB}\parallel\overline{DC}\), and \(\overline{AB}\cong \overline{DC}\)

Prove: \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram

Solution

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. \(\overline{AB}\parallel\overline{DC}\), and \(\overline{AB}\cong \overline{DC}\) | 1. Given |

| 2. \(\angle ABD\cong \angle BDC\) | 2. Alternate Interior Angles |

| 3. \(\overline{DB}\cong \overline{DB}\) | 3. Reflexive \(PoC\) |

| 4. \(\Delta ABD\cong \Delta CDB\) | 4. SAS |

| 5. \(\overline{AD}\cong \overline{BC}\)\) | 5. CPCTC |

| 6. \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram | 6. Opposite Sides Converse |

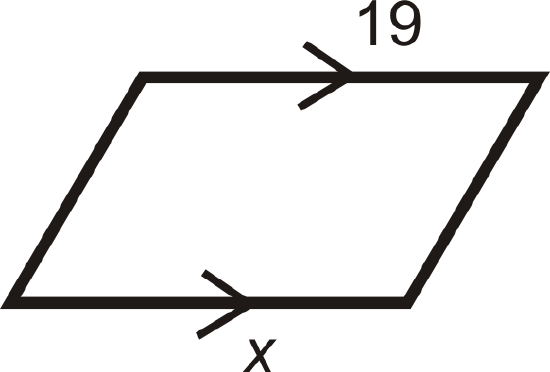

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

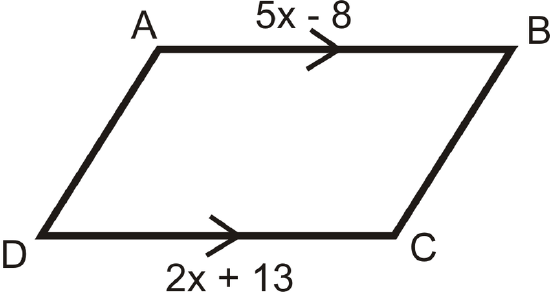

What value of \(x\) would make \(ABCD\) a parallelogram?

Solution

\(\overline{AB}\parallel\overline{DC}\). By the Parallel Congruent Sides Theorem, \(ABCD\) would be a parallelogram if \(AB=DC\).

\(\begin{align*} 5x−8 &=2x+13 \\ 3x &=21 \\ x &=7 \end{align*}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

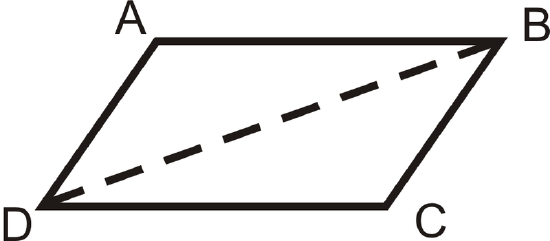

Prove the Opposite Sides Theorem Converse.

Given: \(\overline{AB}\cong \overline{DC}\), \(\overline{AD}\cong \overline{BC}\)

Prove: \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram

Solution

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. \(\overline{AB}\cong \overline{DC}\),\(\overline{AD}\cong \overline{BC}\) | 1.Given |

| 2. \(\overline{DB}\cong \overline{DB}\) | 2. Reflexive \(PoC\) |

| 3. \(\Delta ABD\cong \Delta CDB\) | 3. SSS |

| 4. \(\angle ABD\cong \angle BDC\),\(\angle ADB\cong \angle DBC\) | 4. \(CPCTC\) |

| 5. \(\overline{AB}\parallel\overline{DC}\),\(\overline{AD}\parallel\overline{BC}\) | 5. Alternate Interior Angles Converse |

| 6. \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram | 6. Definition of a parallelogram |

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

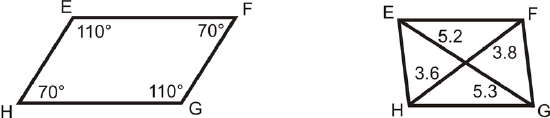

Is quadrilateral \(EFGH\) a parallelogram? How do you know?

Solution

By the Opposite Angles Theorem Converse, \(EFGH\) is a parallelogram.

\(EFGH\) is not a parallelogram because the diagonals do not bisect each other.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

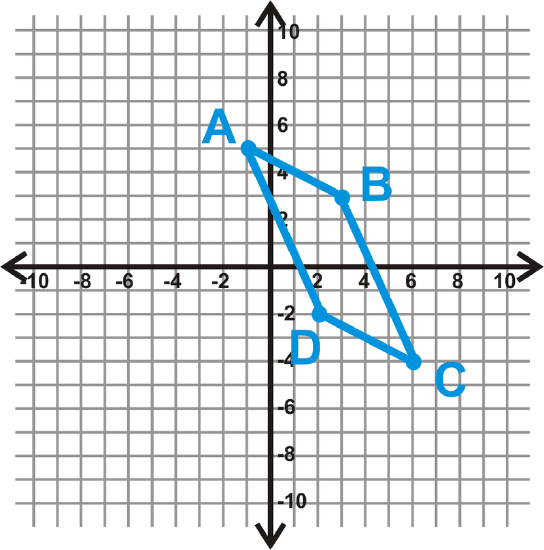

Is the quadrilateral \(ABCD\) a parallelogram?

Solution

Let’s use the Parallel Congruent Sides Theorem to see if \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram. First, find the length of AB and CD using the distance formula.

\(\begin{align*} AB &=\sqrt{(−1−3)^2+(5−3)^2} & CD &=\sqrt{(2−6)^2+(−2+4)^2} \\ &=\sqrt{(−4)^{2}+2^2} & &=\sqrt{(−4)^2+2^2} \\ &=\sqrt{16+4}=\sqrt{20} & & =\sqrt{16+4}=\sqrt{20} \end{align*}\)

Next find the slopes to check if the lines are parallel.

\(\begin{align*} Slope \: AB =\dfrac{5−3}{−1−3} =\dfrac{2}{−4} &=−\dfrac{1}{2} &Slope \: CD=\dfrac{−2+4}{2−6}=\dfrac{2}{−4}=−\dfrac{1}{2} \end{align*}\)

\(AB=CD\) and the slopes are the same (implying that the lines are parallel), so \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram.

Review

For questions 1-12, determine if the quadrilaterals are parallelograms.

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\)

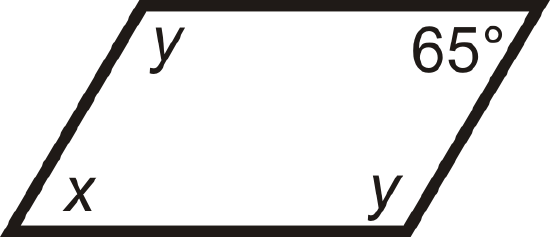

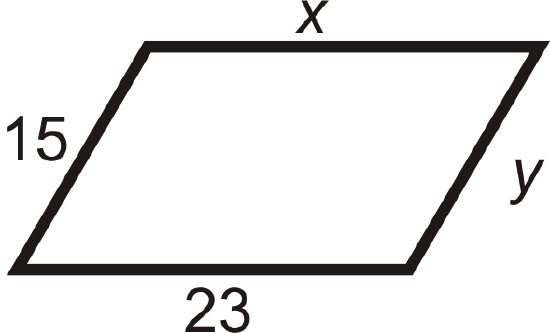

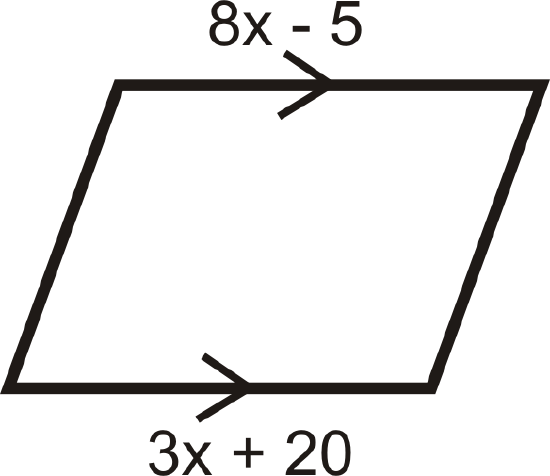

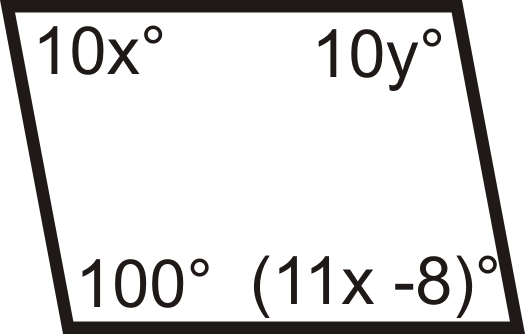

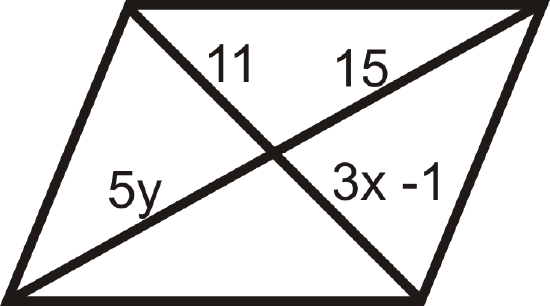

For questions 13-18, determine the value of \(x\) and \(y\) that would make the quadrilateral a parallelogram.

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{26}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{28}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{29}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{30}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{31}\)

For questions 19-22, determine if \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram.

- \(A(8,−1)\), \(B(6,5)\), \(C(−7,2)\), \(D(−5,−4)\)

- \(A(−5,8)\), \(B(−2,9)\), \(C(3,4)\), \(D(0,3)\)

- \(A(−2,6)\), \(B(4,−4)\), \(C(13,−7)\), \(D(4,−10)\)

- \(A(−9,−1)\), \(B(−7,5)\), \(C(3,8)\), \(D(1,2)\)

Fill in the blanks in the proofs below.

- Opposite Angles Theorem Converse

Given: \(\angle A\cong \angle C\), \(\angle D\cong \angle B\)

Prove: \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. \(m\angle A=m\angle C\), \(m\angle D=m\angle B\) | 2. |

| 3. | 3. Definition of a quadrilateral |

| 4. \(m\angle A+m\angle A+m\angle B+m\angle B=360^{\circ}\) | 4. |

| 5. | 5. Combine Like Terms |

| 6. | 6. Division \(PoE\) |

| 7. \(\angle A\) and \(\angle B\) are supplementary \(\angle A\) and \(\angle D\) are supplementary | 7. |

| 8. | 8. Consecutive Interior Angles Converse |

| 9. \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram | 9. |

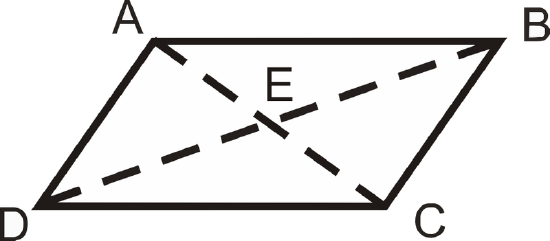

- Parallelogram Diagonals Theorem Converse

Given: \(\overline{AE}\cong \overline{EC}\), \(\overline{DE}\cong \overline{EB}\)

Prove: \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. | 2. Vertical Angles Theorem |

|

3. \(\Delta AED \cong \Delta CEB\) \(\Delta AEB\cong \Delta CED\) |

3. |

| 4. | 4. |

| 5. \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram | 5. |

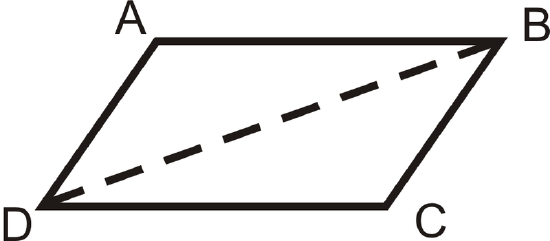

- Given: \(\angle ADB\cong \angle CBD\), \(\overline{AD}\cong \overline{BC}\)

Prove: \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. \(\overline{AD}\parallel\overline{BC}\) | 2. |

| 3. \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram | 3. |

Review (Answers)

To see the Review answers, open this PDF file and look for section 6.4.

Additional Resources

Interactive Element

Video: Proving a Quadrilateral is a Parallelogram Principles - Basic

Activities: Quadrilaterals that are Parallelograms Discussion Questions

Study Aids: Parallelograms Study Guide

Practice: Parallelogram Proofs

Real World: Quadrilaterals That Are Parallelograms