4.20: Perpendicular Bisectors

- Page ID

- 4817

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Intersect line segments at their midpoints and form 90 degree angles with them.

Perpendicular Bisector Theorem

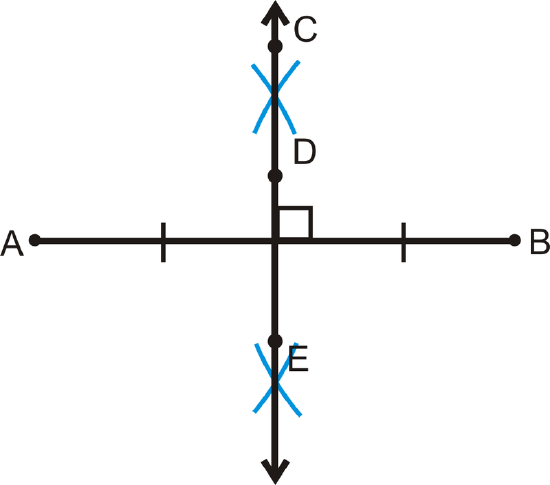

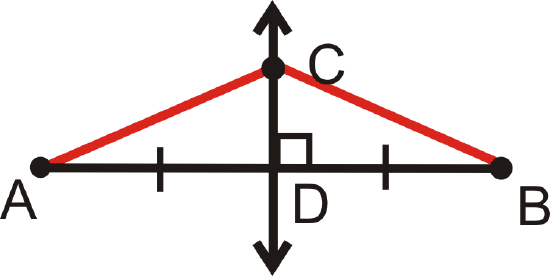

A perpendicular bisector is a line that intersects a line segment at its midpoint and is perpendicular to that line segment, as shown in the construction below.

One important property related to perpendicular bisectors is that if a point is on the perpendicular bisector of a segment, then it is equidistant from the endpoints of the segment. This is called the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem.

If \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\perp \overline{AB}\) and \(AD=DB\), then \(AC=CB\).

In addition to the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem, the converse is also true.

Perpendicular Bisector Theorem Converse: If a point is equidistant from the endpoints of a segment, then the point is on the perpendicular bisector of the segment.

Using the picture above: If \(AC=CB\), then \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\perp \overline{AB}\) and \(AD=DB\).

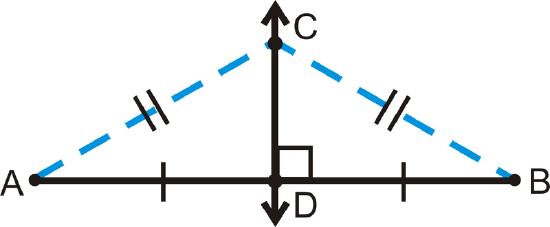

When we construct perpendicular bisectors for the sides of a triangle, they meet in one point. This point is called the circumcenter of the triangle.

What if you were given \(\Delta FGH\) and told that \(\overleftrightarrow{GJ}\) was the perpendicular bisector of \(\overline{FH}\)? How could you find the length of FG given the length of GH\)?

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

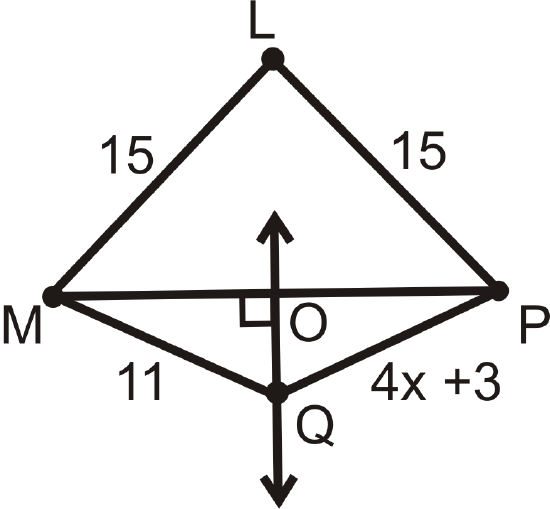

\(\overleftrightarrow{OQ}\) is the perpendicular bisector of \(\overline{MP}\).

Which line segments are equal? Find \(x\). Is \(L\) on \(\overleftrightarrow{OQ}\)? How do you know?

Solution

\(ML=LP\), \(MO=OP\), and \(MQ=QP\).

\(\begin{align*} 4x+3&=11 \\ 4x&=8 \\ x&=2\end{align*} \)

Yes, \(L\) is on \(\overleftrightarrow{OQ}\) because \(ML=LP\) (the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem Converse).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

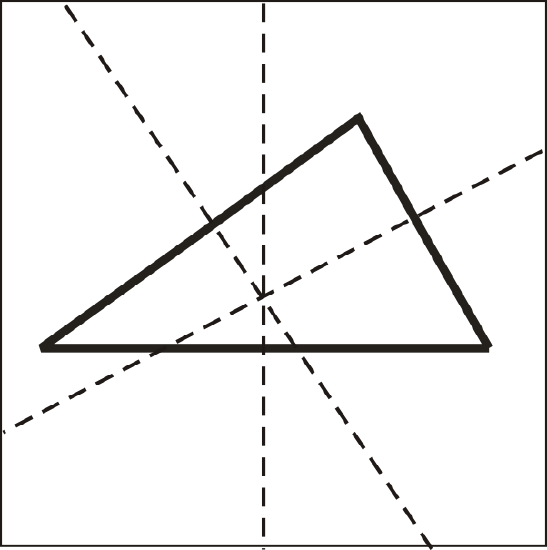

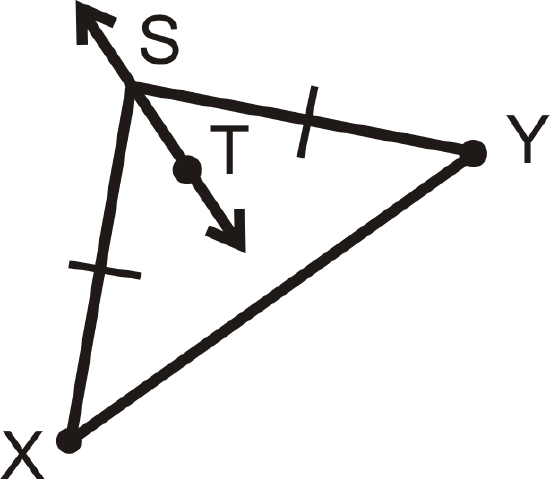

Determine if \(\overleftrightarrow{ST}\) is the perpendicular bisector of \(\overline{XY}\). Explain why or why not.

Solution

\(\overleftrightarrow{ST}\) is not necessarily the perpendicular bisector of \(\overline{XY}\) because not enough information is given in the diagram. There is no way to know from the diagram if \(\overleftrightarrow{ST}\) will extend to make a right angle with \(\overline{XY}\).

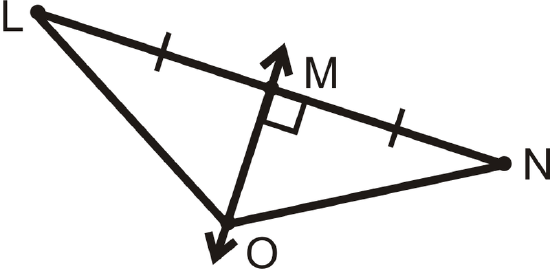

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

If \(\overleftrightarrow{MO}\)− is the perpendicular bisector of \(\overline{LN}\) and \(LO=8\), what is \(ON\)?

Solution

By the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem, \(LO=ON\). So, \(ON=8\).

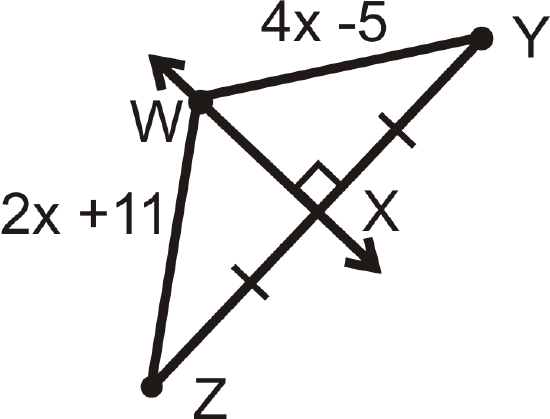

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Find \(x\) and the length of each segment.

Solution

\(\overleftrightarrow{WX}\)− is the perpendicular bisector of \(\overline{XZ}\) and from the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem \(WZ=WY\).

\(\begin{align*} 2x+11&=4x−5 \\ 16&=2x \\ 8&=x \end{align*}\)

\(WZ=WY=2(8)+11=16+11=27\).

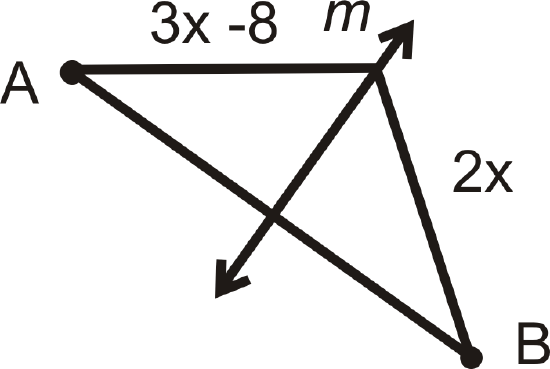

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Find the value of \(x\). \(m\) is the perpendicular bisector of \(AB\).

Solution

By the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem, both segments are equal. Set up and solve an equation.

\(\begin{align*}3x−8&=2x \\ x&=8 \end{align*} \)

Review

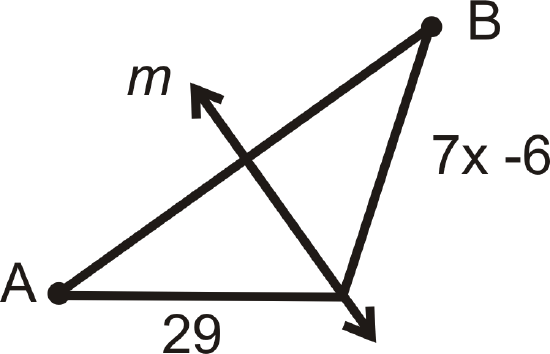

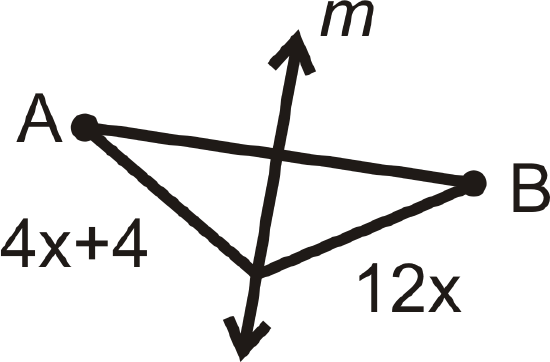

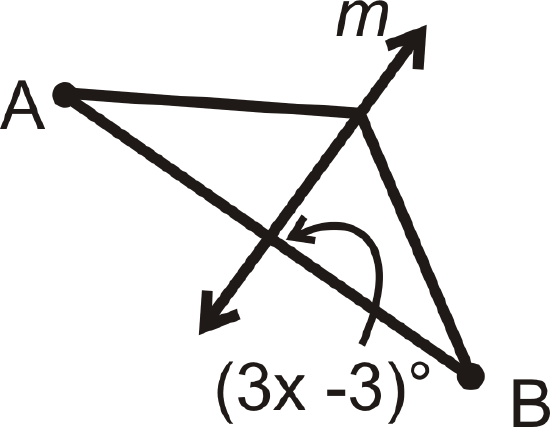

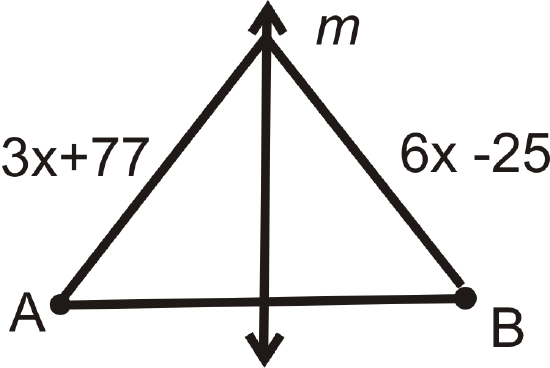

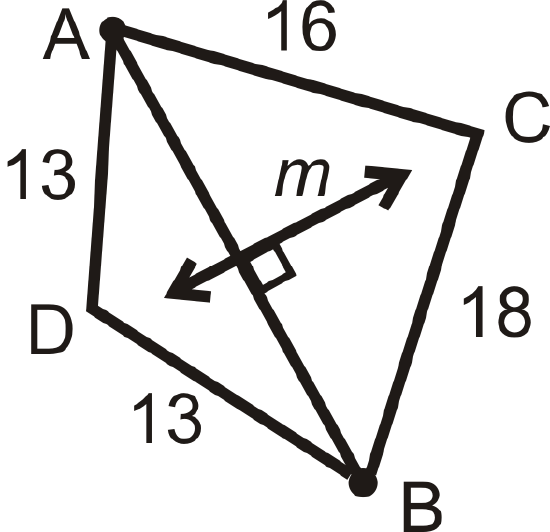

For questions 1-4, find the value of \(x\). m\) is the perpendicular bisector of\( AB\).

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)

m is the perpendicular bisector of \(\overline{AB}\).

- List all the congruent segments.

- Is \(C\) on \(m\)? Why or why not?

- Is \(D\) on \(m\)? Why or why not?

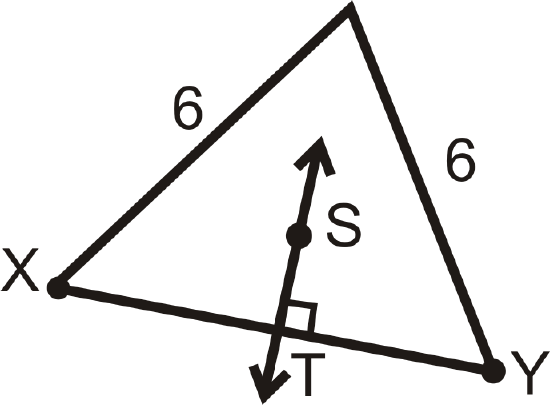

For Question 8, determine if \(\overleftrightarrow{ST}\) is the perpendicular bisector of \overline{XY}\). Explain why or why not.

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) - In what type of triangle will all perpendicular bisectors pass through vertices of the triangle?

- Fill in the blanks of the proof of the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem.

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)

Given: \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\) is the perpendicular bisector of \(\overline{AB}\)

Prove: \(\overline{AC}\cong \overline{CB}\)

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. \(D\) is the midpoint of \(\overline{AB}\) | 2. |

| 3. | 3. Definition of a midpoint |

| 4. \(\angle CDA\) and \(\angle CDB\) are right angles | 4. |

| 5. \(\angle CDA\cong \angle CDB\) | 5. |

| 6. | 6. Reflexive PoC |

| 7. \(\Delta CDA\cong \Delta CDB\) | 7. |

| 8. \(\overline{AC}\cong \overline{CB}\) | 8. |

Review (Answers)

To see the Review answers, open this PDF file and look for section 5.2.

Vocabulary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| circumcenter | The circumcenter is the point of intersection of the perpendicular bisectors of the sides in a triangle. |

| perpendicular bisector | A perpendicular bisector of a line segment passes through the midpoint of the line segment and intersects the line segment at \(90^{\circ}\). |

| Perpendicular Bisector Theorem Converse | If a point is equidistant from the endpoints of a segment, then the point is on the perpendicular bisector of the segment. |

Additional Resources

Interactive Element

Video: Perpendicular Bisectors Principles - Basic

Activites: Perpendicular Bisectors Discussion Questions

Study Aid: Bisectors, Medians, Altitudes Study Guide

Practice: Perpendicular Bisectors

Real World: Perpendicular Bisectors