4.21: Angle Bisectors in Triangles

- Page ID

- 4818

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Construction and properties of bisectors, which cut angles in half.

Angle Bisector Theorem

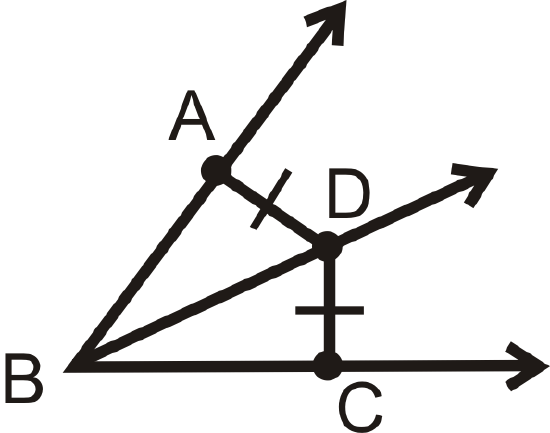

An angle bisector cuts an angle exactly in half. One important property of angle bisectors is that if a point is on the bisector of an angle, then the point is equidistant from the sides of the angle. This is called the Angle Bisector Theorem.

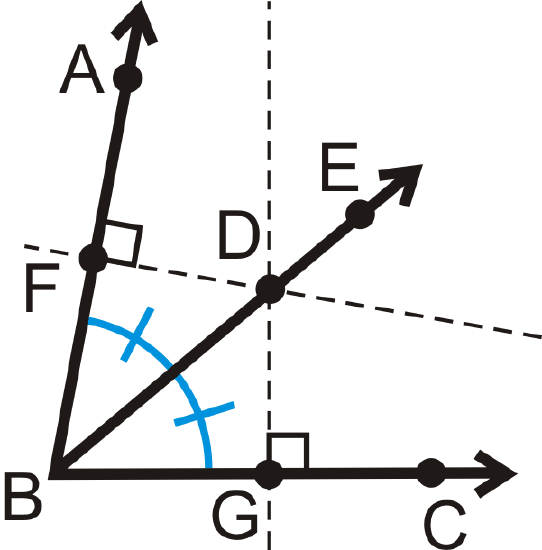

In other words, if \(\overrightarrow{BD}\) bisects \(\angle ABC\), \(\overrightarrow{BA}\perp FD\overline{AB}\), and, \(\overrightarrow{BC}\perp \overline{DG}\) then \(FD=DG\).

The converse of this theorem is also true.

Angle Bisector Theorem Converse: If a point is in the interior of an angle and equidistant from the sides, then it lies on the bisector of that angle.

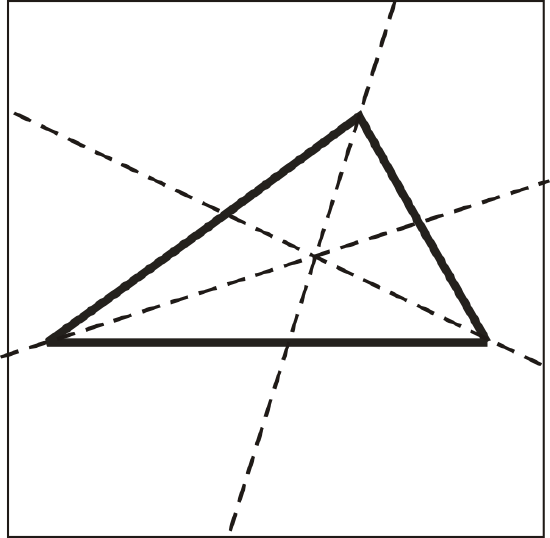

When we construct angle bisectors for the angles of a triangle, they meet in one point. This point is called the incenter of the triangle.

What if you were told that \(\overrightarrow{GJ}\) is the angle bisector of \(\angle FGH\)? How would you find the length of \(FJ\) given the length of \(HJ\)?

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

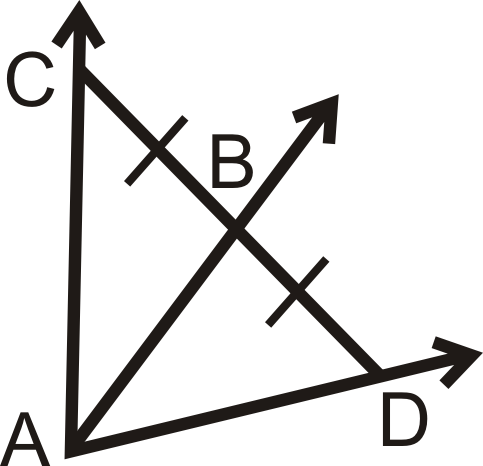

Is there enough information to determine if \(\overrightarrow{AB}\) is the angle bisector of \(\angle CAD\)? Why or why not?

Solution

No because \(B\) is not necessarily equidistant from \(\overline{AC}\) and \(\overline{AD}\). We do not know if the angles in the diagram are right angles.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

A \(108^{\circ}\) angle is bisected. What are the measures of the resulting angles?

Solution

We know that to bisect means to cut in half, so each of the resulting angles will be half of 108. The measure of each resulting angle is \(54^{\circ}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

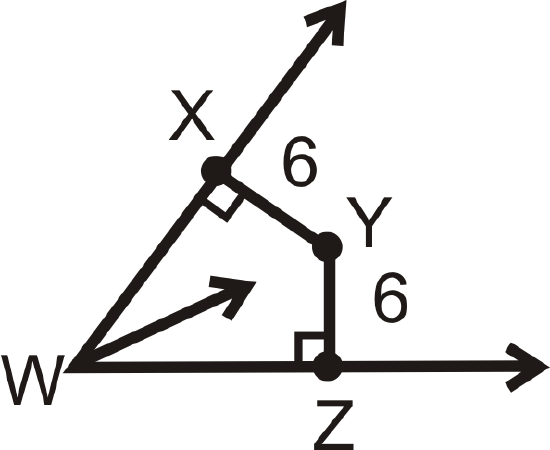

Is \(Y\) on the angle bisector of \(\angle XWZ\)?

Solution

If \(Y\) is on the angle bisector, then \(XY=YZ\) and both segments need to be perpendicular to the sides of the angle. From the markings we know \(\overline{XY}\perp \overrightarrow{WX}\) and \(\overline{ZY}\perp \overrightarrow{WZ}\). Second, \(XY=YZ=6\). So, yes, \(Y\) is on the angle bisector of \(\angle XWZ\).

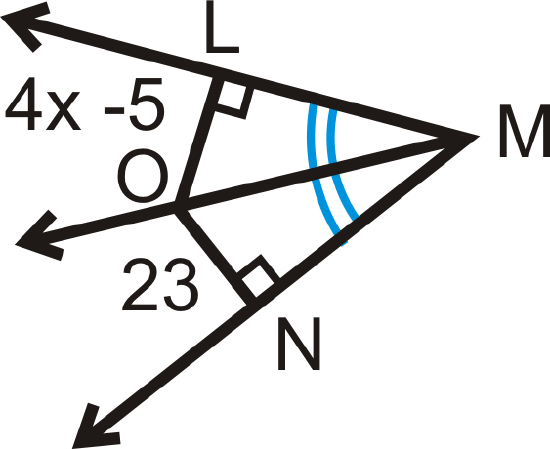

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

\(\overrightarrow{MO}\) is the angle bisector of \(\angle LMN\). Find the measure of \(x\).

Solution

\(LO=ON\) by the Angle Bisector Theorem.

\(\begin{align*} 4x−5&=23 \\ 4x&=28 \\ x&=7\end{align*} \)

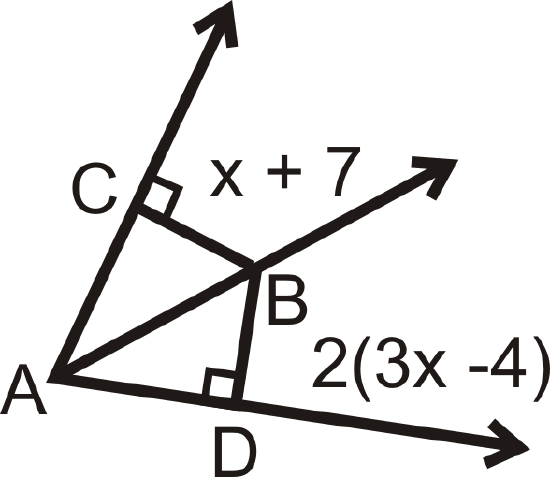

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

\(\overrightarrow{AB}\) is the angle bisector of \(\angle CAD\). Solve for the missing variable.

Solution

\(CB=BD\) by the Angle Bisector Theorem, so we can set up and solve an equation for \(x\).

\(\begin{align*} x+7&=2(3x−4) \\ x+7&=6x−8 \\ 15x&=5 \\ x&=3\end{align*}\)

Review

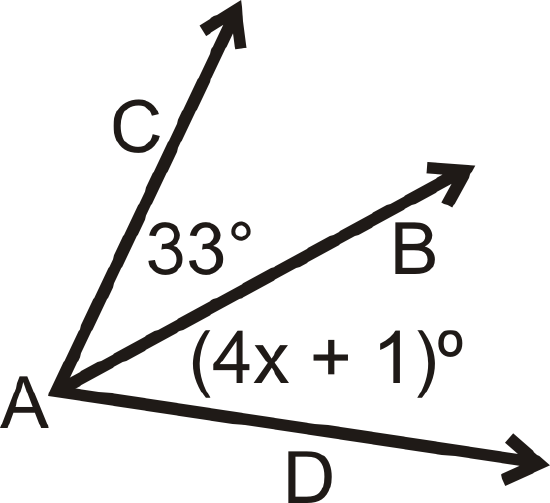

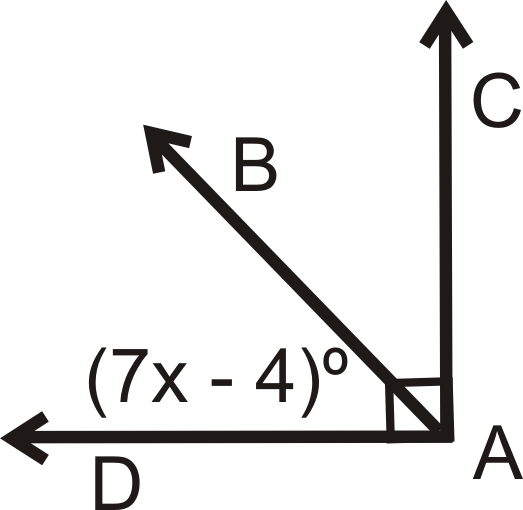

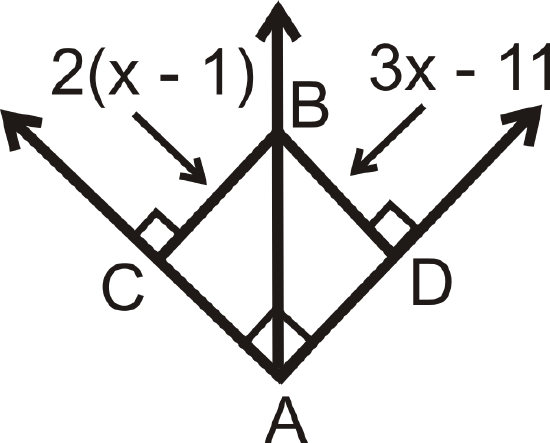

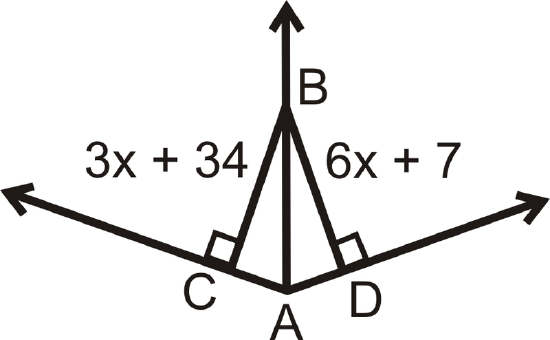

For questions 1-4, \(\overrightarrow{AB}\) is the angle bisector of \(\angle CAD\). Solve for the missing variable.

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)

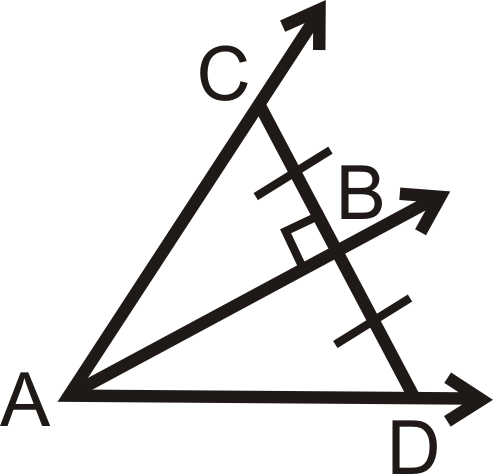

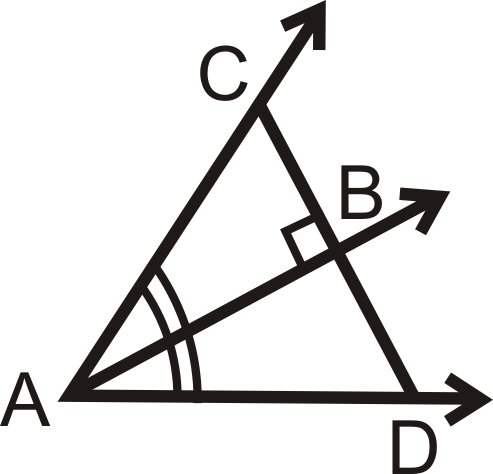

Is there enough information to determine if \(\overrightarrow{AB}\) is the angle bisector of \angle CAD? Why or why not?

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)

- In what type of triangle will all angle bisectors pass through vertices of the triangle?

- What is another name for the angle bisectors of the vertices of a square?

- Draw in the angle bisectors of the vertices of a square. How many triangles do you have? What type of triangles are they?

- Fill in the blanks in the Angle Bisector Theorem Converse.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)

Given: \(\overline{AD}\cong \overline{DC}\), such that \(AD\) and \(DC\) are the shortest distances to \(\overrightarrow{BA}\) and \(\overrightarrow{BC}\)

Prove: \(\overrightarrow{BD} bisects \angle ABC\)

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. | 2. The shortest distance from a point to a line is perpendicular. |

| 3. \(\angle DAB \)and \(\angle DCB\) are right angles | 3. |

| 4. \(\angle DAB\cong \angle DCB\) | 4. |

| 5. \(\overline{BD}\cong \overline{BD}\) | 5. |

| 6. \(\Delta ABD\cong \Delta CBD\) | 6. |

| 7. | 7. CPCTC |

| 8. \(\overrightarrow{BD}\) bisects \(\angle ABC\) | 8. |

Review (Answers)

To see the Review answers, open this PDF file and look for section 5.3.

Resources

Vocabulary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| angle bisector | An angle bisector is a ray that splits an angle into two congruent, smaller angles. |

| Angle Bisector Theorem | The angle bisector theorem states that if a point is on the bisector of an angle, then the point is equidistant from the sides of the angle. |

| Angle Bisector Theorem Converse | The angle bisector theorem converse states that if a point is in the interior of an angle and equidistant from the sides, then it lies on the bisector of that angle. |

| incenter | The incenter is the point of intersection of the angle bisectors in a triangle. |

Additional Resources

Interactive Element

Video: Examples: Solving For Unknown Values Using Properties of Angle Bisectors

Activities: Angle Bisectors in Triangles Discussion Questions

Study Aids: Bisectors, Medians, Altitudes Study Guide

Practice: Angle Bisectors in Triangles

Real World: Perpendicular Bisectors