5.9: Parallelograms

- Page ID

- 4993

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Find unknown angle measurements of quadrilaterals with two pairs of parallel sides.

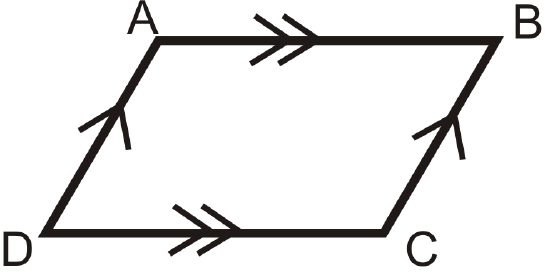

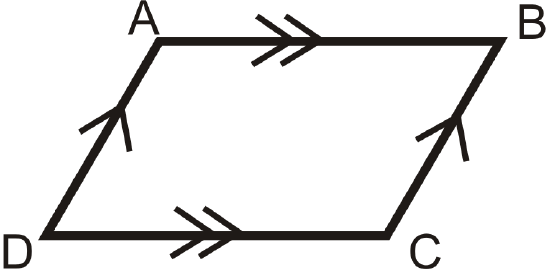

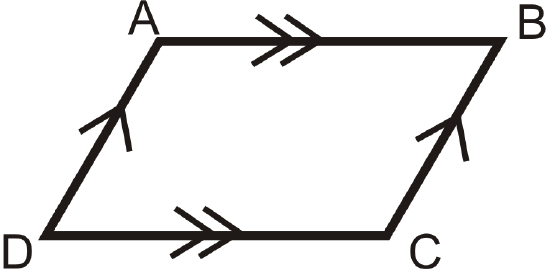

A parallelogram is a quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides.

Notice that each pair of sides is marked parallel (for the last two shapes, remember that when two lines are perpendicular to the same line then they are parallel). Parallelograms have a lot of interesting properties.

Facts about Parallelograms

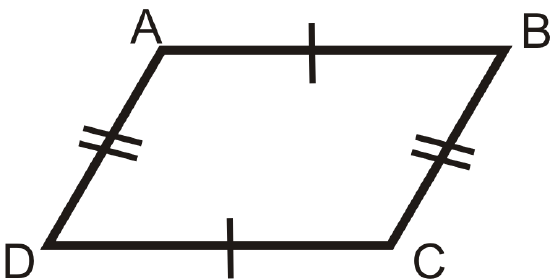

- Opposite Sides Theorem: If a quadrilateral is a parallelogram, then both pairs of opposite sides are congruent.

If

then

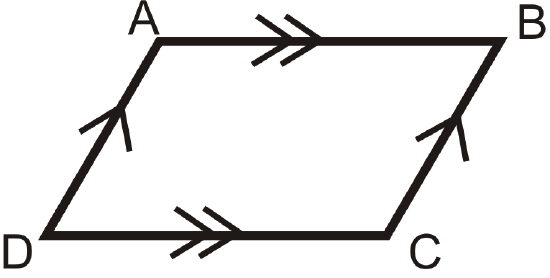

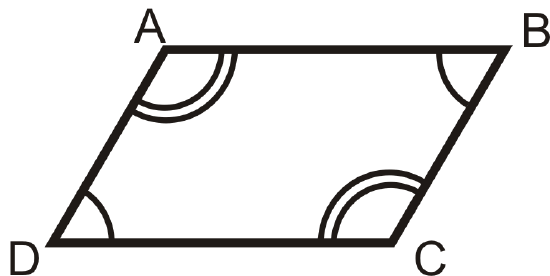

2. Opposite Angles Theorem: If a quadrilateral is a parallelogram, then both pairs of opposite angles are congruent.

If

then

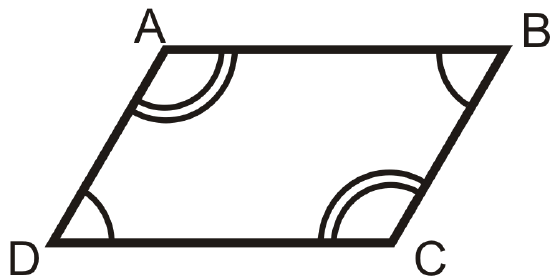

3. Consecutive Angles Theorem: If a quadrilateral is a parallelogram, then all pairs of consecutive angles are supplementary.

If

then

\(\begin{aligned} m\angle A+m\angle D&=180^{\circ} \\ m\angle A+m\angle B&=180^{\circ} \\ m\angle B+m\angle C&=180^{\circ} \\ m\angle C+m\angle D&=180^{\circ} \end{aligned}\)

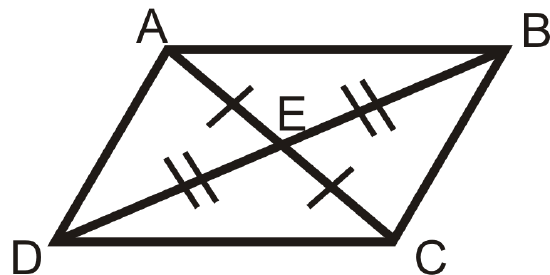

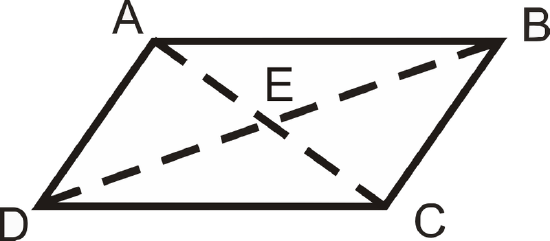

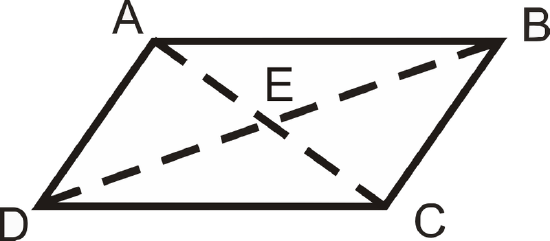

4. Parallelogram Diagonals Theorem: If a quadrilateral is a parallelogram, then the diagonals bisect each other.

If

then

What if you were told that \(FGHI\) is a parallelogram and you are given the length of FG\) and the measure of \(\angle F\)? What can you determine about \(HI\), \(\angle H\), \(\angle G\), and \(\angle I\)?

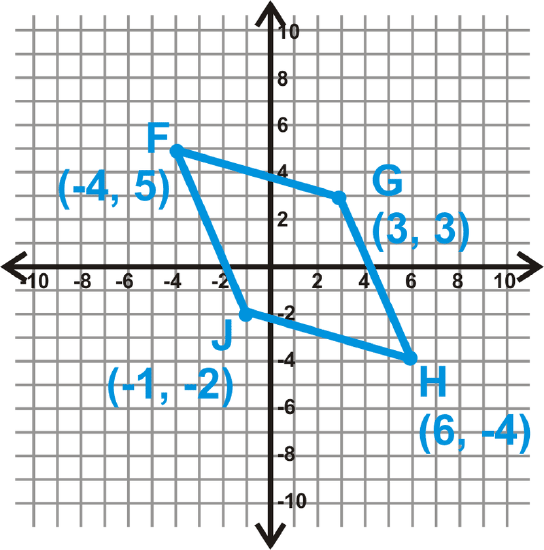

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Show that the diagonals of \(FGHJ\) bisect each other.

Solution

Find the midpoint of each diagonal.

\(\begin{aligned}\text{ Midpoint of } \overline{FH}:& \left(\dfrac{−4+6}{2}, \dfrac{5−4}{2}\right)=(1,0.5) \\ \text{ Midpoint of } of\: \overline{GJ}: & \left(\dfrac{3−1}{2}, \dfrac{3−2}{2}\tight)=(1,0.5)\end{aligned}\)

Because they are the same point, the diagonals intersect at each other’s midpoint. This means they bisect each other.

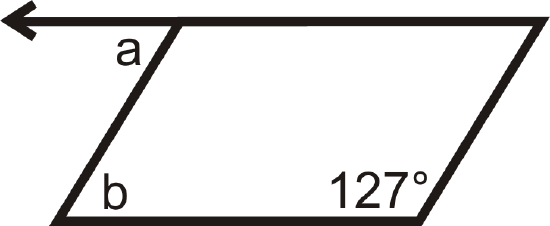

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Find the measures of a and b in the parallelogram below:

Solution

Consecutive angles are supplementary so \(127^{\circ}+m\angle b=180^{\circ}\) which means that \(m\angle b=53^{\circ}\). \(a\) and \(b\) are alternate interior angles and since the lines are parallel (since its a parallelogram), that means that \(m\angle a=m\angle b=53^{\circ}\).

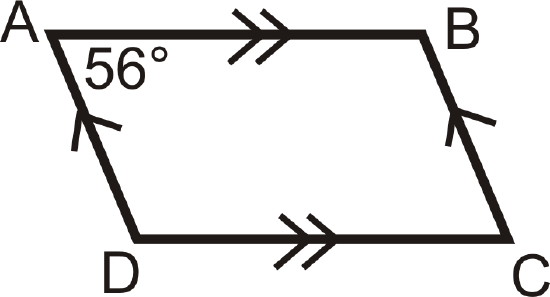

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

\(ABCD\) is a parallelogram. If \(m\angle A=56^{\circ}\), find the measure of the other angles.

Solution

First draw a picture. When labeling the vertices, the letters are listed, in order.

If \(m\angle A=56^{\circ}\), then \(m\angle C=56^{\circ}\) by the Opposite Angles Theorem.

\(\begin{aligned}

&m \angle A+m \angle B=180^{\circ} \quad \text { by the Consecutive Angles Theorem. }\\

&56^{\circ}+m \angle B=180^{\circ}\\

&m \angle B=124^{\circ} \quad m \angle D=124^{\circ} \quad \text { because it is an opposite angle to } \angle B

\end{aligned}\)

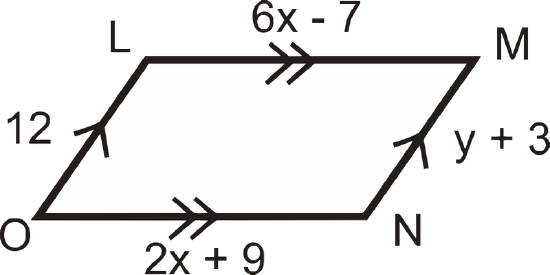

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Find the values of \(x\) and \(y\).

Solution

Remember that opposite sides of a parallelogram are congruent. Set up equations and solve.

\(\begin{aligned} 6x−7&=2x+9 \\ 4x&=16 \\ x&=4 \\ y+3&=12 \\ y&=9\end{aligned} \)

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Prove the Opposite Sides Theorem.

Solution

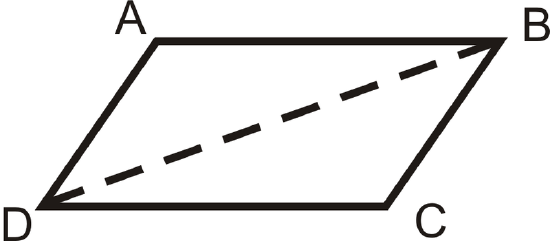

Given: \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram with diagonal \(\overline{BD}\)

Prove: \(\overline{AB}\cong \overline{DC}\), \(\overline{AD}\cong \overline{BC} \)

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram with diagonal \(\overline{BD}\) | 1. Given |

| 2. \(\overline{AB}\parallel \overline{DC}\), \(\overline{AD}\parallel \overline{BC}\) | 2. Definition of a parallelogram |

| 3. \(\angle ABD\cong \angle BDC\), \(\angle ADB\cong \angle DBC\) | 3. Alternate Interior Angles Theorem |

| 4. \(\overline{DB}\cong \overline{DB}\) | 4. Reflexive PoC |

| 5. \(\Delta ABD\cong \Delta CDB\) | 5. ASA |

| 6. \(\overline{AB}\cong \overline{DC}\), \(\overline{AD}\cong \overline{BC}\) | 6. CPCTC |

The proof of the Opposite Angles Theorem is almost identical.

Review

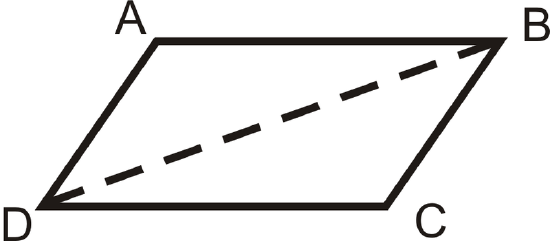

\(ABCD\) is a parallelogram. Fill in the blanks below.

- If \(AB=6\), then \(CD= \text{______}\).

- If \(AE=4\), then \(AC= \text{______}\).

- If \(m\angle ADC=80^{\circ}\), \(m\angle DAB = \text{______}\).

- If \(m\angle BAC=45^{\circ}\), \(m\angle ACD = \text{______}\).

- If \(m\angle CBD=62^{\circ}\), \(m\angle ADB = \text{______}\).

- If \(DB=16\), then \(DE = \text{______}\).

- If\( m\angle B=72^{\circ}\) in parallelogram \(ABCD\), find the other three angles.

- If \(m\angle S=143^{\circ}\) in parallelogram \(PQRS\), find the other three angles.

- If \(\overline{AB}\perp \overline{BC}\) in parallelogram \(ABCD\), find the measure of all four angles.

- If \(m\angle F=x^{\circ}\) in parallelogram \(EFGH\), find the other three angles.

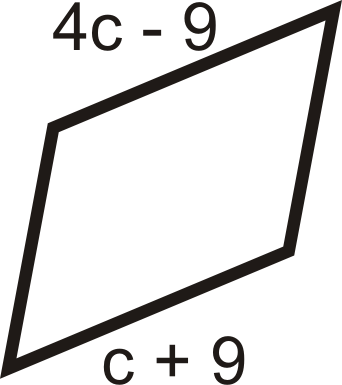

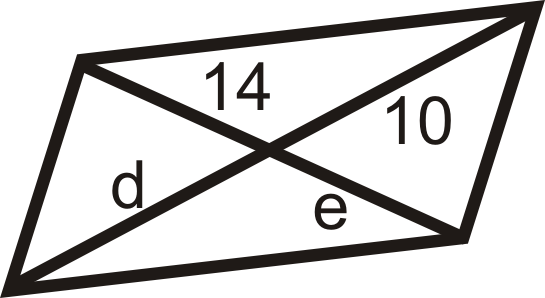

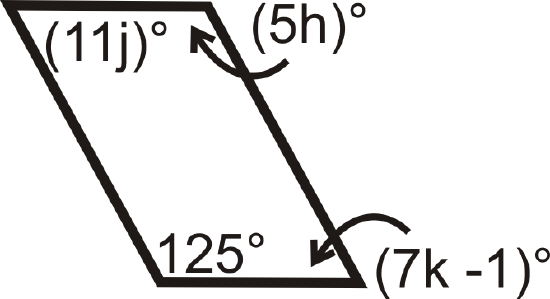

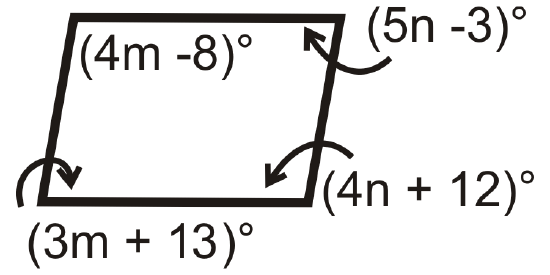

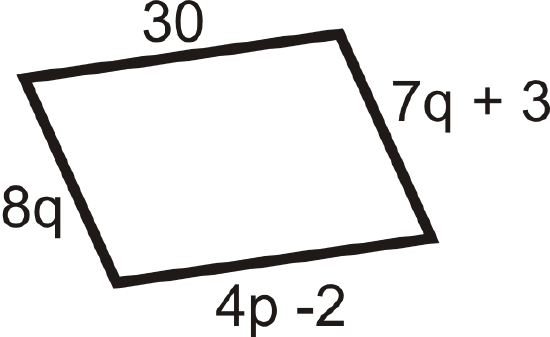

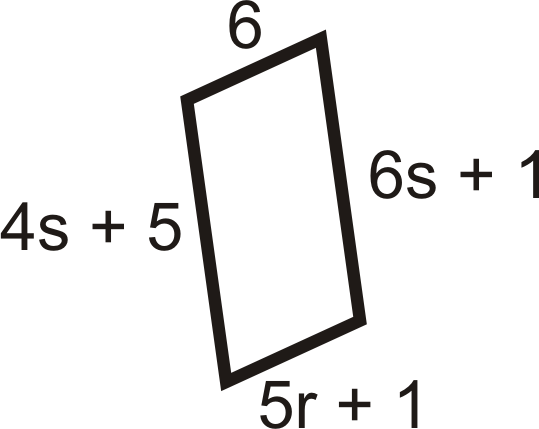

For questions 11-18, find the values of the variable(s). All the figures below are parallelograms.

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\)

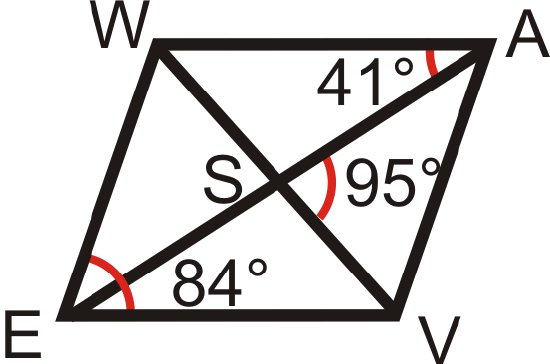

Use the parallelogram \(WAVE\) to find:

- \(m\angle AWE\)

- \(m\angle ESV\)

- \(m\angle WEA\)

- \(m\angle AVW\)

Find the point of intersection of the diagonals to see if \(EFGH\) is a parallelogram.

- \(E(−1,3), F(3,4), G(5,−1), H(1,−2)\)

- \(E(3,−2), F(7,0), G(9,−4), H(5,−4)\)

- \(E(−6,3), F(2,5), G(6,−3), H(−4,−5)\)

- \(E(−2,−2), F(−4,−6), G(−6,−4), H(−4,0)\)

Fill in the blanks in the proofs below.

- Opposite Angles Theorem

Given: \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram with diagonal \(\overline{BD}\)

Prove: \(\angle A\cong \angle C\)

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. | 1. Given |

| 2. \(\overline{AB}\parallel \overline{DC}\), \(\overline{AD}\parallel \overline{BC}\) | 2. |

| 3. | 3. Alternate Interior Angles Theorem |

| 4. | 4. Reflexive PoC |

| 5. \(\Delta ABD\cong \Delta CDB\) | 5. |

| 6. \(\angle A\cong \angle C\) | 6. |

- Parallelogram Diagonals Theorem

Given: \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram with diagonals \(\overline{BD}\) and \(\overline{AC}\)

Prove: \(\overline{AE}\cong \overline{EC}\), \(\overline{DE}\cong \overline{EB}\)

| Statement | Reason |

|---|---|

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. | 2. Definition of a parallelogram |

| 3. | 3. Alternate Interior Angles Theorem |

| 4. \(\overline{AB}\cong \overline{DC}\) | 4. |

| 5. | 5. |

| 6.\( \overline{AE}\cong \overline{EC}\),\(\overline{DE}\cong \overline{EB}\) | 6. |

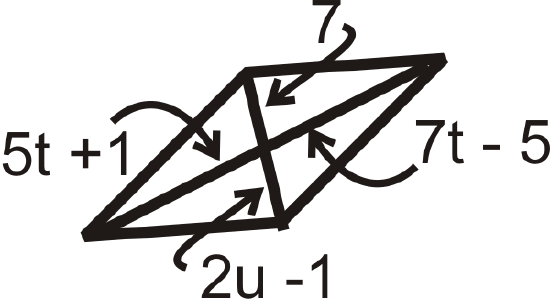

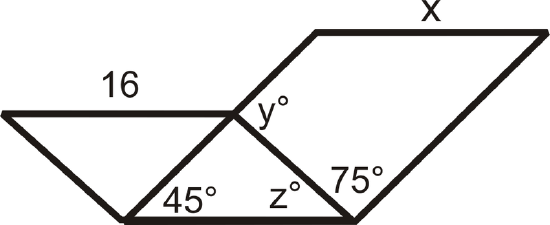

- Find \(x\), \(y^{\circ}\), and \(z^{\circ}\). (The two quadrilaterals with the same side are parallelograms.)

Vocabulary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| parallelogram | A quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides. A parallelogram may be a rectangle, a rhombus, or a square, but need not be any of the three. |

Additional Resources

Interactive Element

Video: Parallelograms Principles - Basic

Activities: Parallelograms Discussion Questions

Study Aids: Parallelograms Study Guide

Practice: Parallelograms

Real World: Parallelograms