3.9: Parallel Lines in the Coordinate Plane

- Page ID

- 4771

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Lines with the same slope that never intersect.

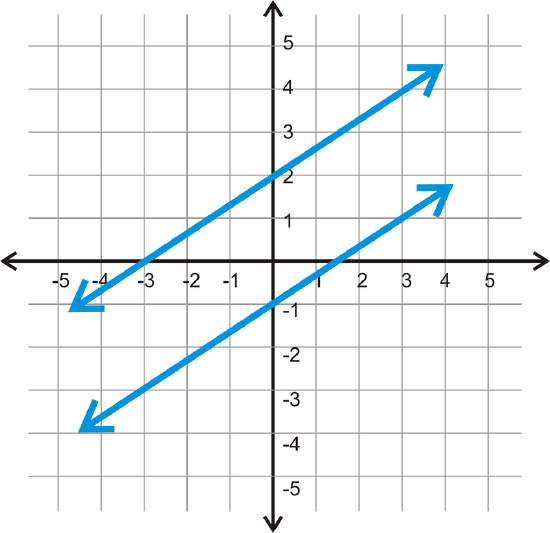

Parallel lines are two lines that never intersect. In the coordinate plane, that would look like this:

If we take a closer look at these two lines, the slopes are both \(\dfrac{2}{3}\).

This can be generalized to any pair of parallel lines. Parallel lines always have the same slope and different \(y\)−intercepts.

What if you were given two parallel lines in the coordinate plane? What could you say about their slopes?

Video

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Find the equation of the line that is parallel to \(y=\dfrac{1}{4}x+3\) and passes through \((8, -7)\).

Solution

We know that parallel lines have the same slope, so the line will have a slope of \(dfrac{1}{4}\). Now, we need to find the \(y\)−intercept. Plug in 8 for x and -7 for \(y\) to solve for the new \(y\)−intercept (b).

\(\begin{align*}−7=\dfrac{1}{4} (8)+b \\ −7&=2+b \\ −9 &=b \end{align*}\)

The equation of the parallel line is \(y=\dfrac{1}{4}x−9\).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Are the lines \(3x+4y=7\) and \(y=\dfrac{3}{4} x+1\) parallel?

Solution

First we need to rewrite the first equation in slope-intercept form.

\(\begin{align*}3x+4y &=7 \\ 4y &=−3x+7 \\ y &=−\dfrac{3}{4}x+\dfrac{7}{4} \end{align*}\).

The slope of this line is \(−\dfrac{3}{4}\) while the slope of the other line is \(\dfrac{3}{4}\). Because the slopes are different the lines are not parallel.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Find the equation of the line that is parallel to \(y=−\dfrac{1}{3} x+4\) and passes through \((9, -5)\).

Solution

Recall that the equation of a line is y=mx+b, where m is the slope and b is the \(y\)−intercept. We know that parallel lines have the same slope, so the line will have a slope of −13. Now, we need to find the \(y\)−intercept. Plug in 9 for \(x\) and -5 for \(y\) to solve for the new \(y\)−intercept (b).

\(\begin{align*}−5&=−\dfrac{1}{3} (9)+b \\ −5&=−3+b \\−2&=b\end{align*}\)

The equation of parallel line is \(y=−\dfrac{1}{3} x−2\).

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

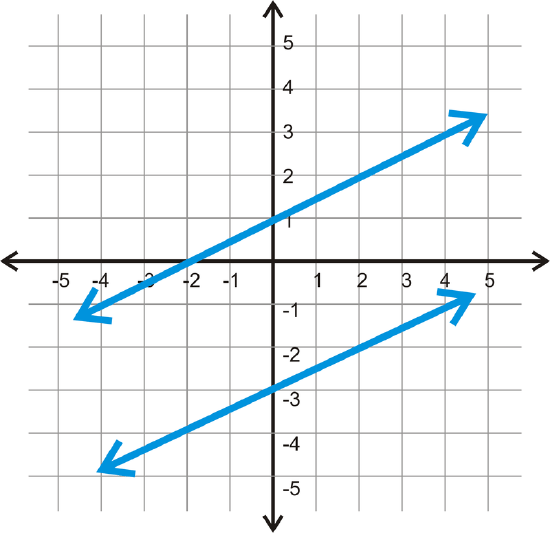

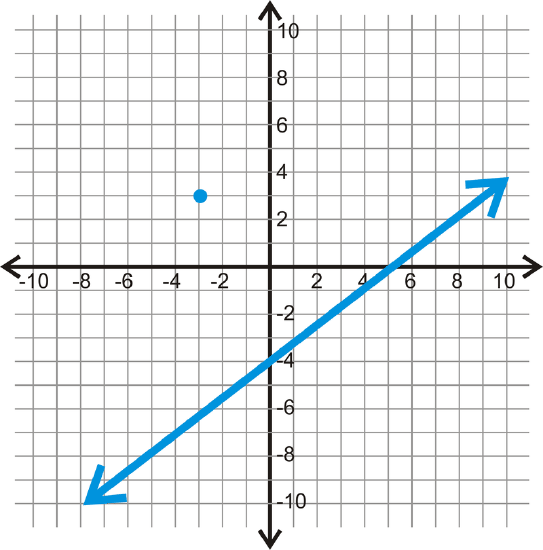

Find the equation of the lines below and determine if they are parallel.

Solution

The top line has a \(y\)−intercept of 1. From there, use “rise over run” to find the slope. From the \(y\)−intercept, if you go up 1 and over 2, you hit the line again, \(m=\dfrac{1}{2}\). The equation is \(y=\dfrac{1}{2} x+1\).

For the second line, the \(y\)−intercept is -3. The “rise” is 1 and the “run” is 2 making the slope \(\dfrac{1}{2}\). The equation of this line is \(y=\dfrac{1}{2} x−3\).

The lines are parallel because they have the same slope.

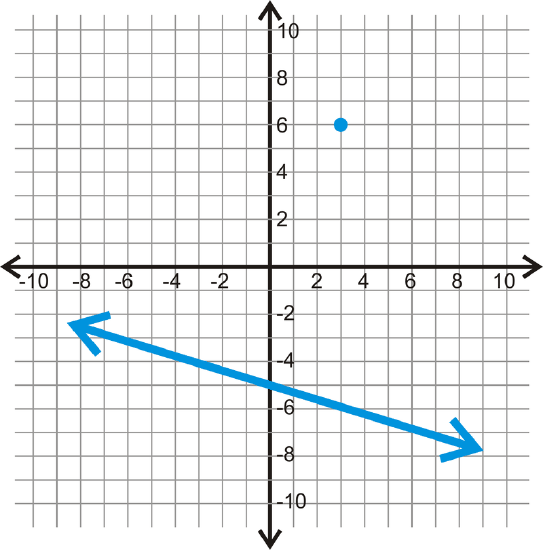

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

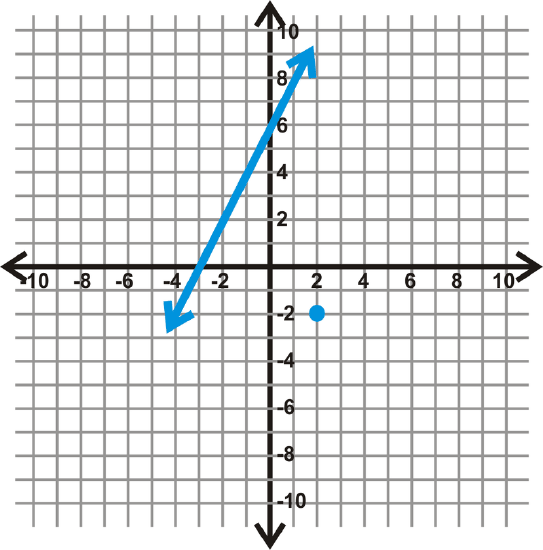

Find the equation of the line that is parallel to the line through the point marked with a blue dot.

Solution

First, notice that the equation of the line is \(y=2x+6\) and the point is \((2, -2)\). The parallel would have the same slope and pass through \((2, -2)\).

\(\begin{align*}y &=2x+b \\ −2 &=2(2)+b \\ −2&=4+b \\−6&=b \end{align*}\)

The equation of the parallel line is \(y=2x+−6\).

Review

Determine if each pair of lines are parallel. Then, graph each pair on the same set of axes.

- \(y=4x−2\) and \(y=4x+5\)

- \(y=−x+5\) and \(y=x+1\)

- \(5x+2y=−4\) and \(5x+2y=8\)

- \(x+y=6\) and \(4x+4y=−16\)

Determine the equation of the line that is parallel to the given line, through the given point.

- \(y=−5x+1; (−2,3)\)

- \(y=\dfrac{2}{3}x−2; (9,1)\)

- \(x−4y=12; (−16,−2)\)

- \(3x+2y=10; (8,−11)\)

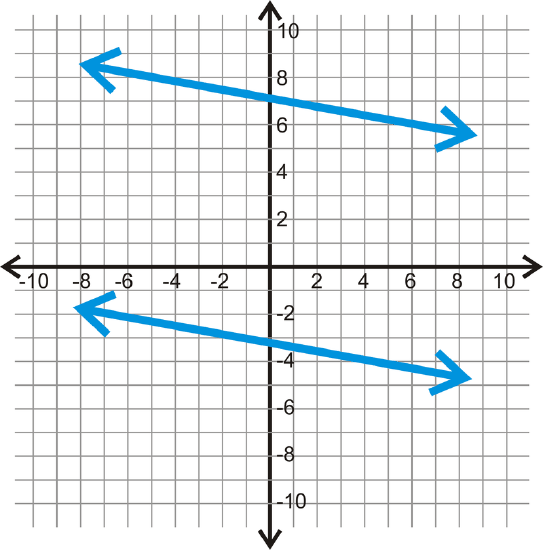

Find the equation of the two lines in each graph below. Then, determine if the two lines are parallel.

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)

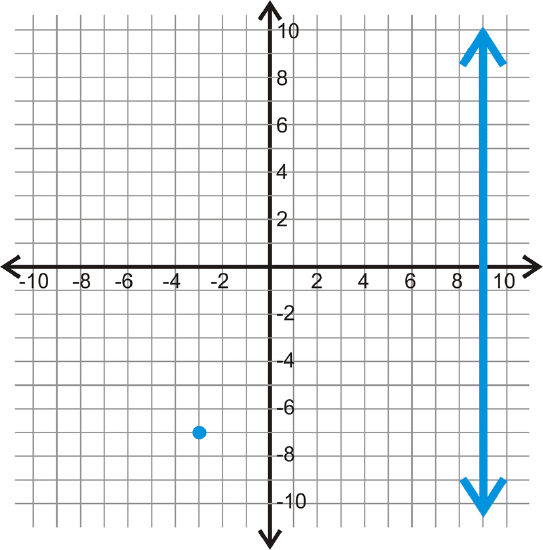

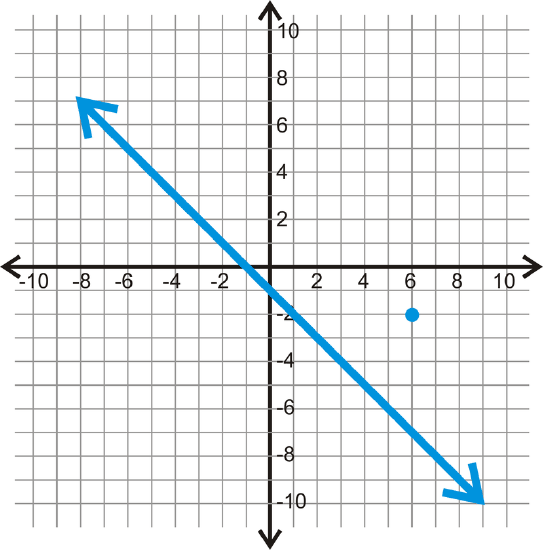

For the line and point below, find a parallel line, through the given point.

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) -

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Review (Answers)

To see the Review answers, open this PDF file and look for section 3.8.

Vocabulary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Parallel | Two or more lines are parallel when they lie in the same plane and never intersect. These lines will always have the same slope. |

Additional Resource

Interactive Element

Video: Equations of Parallel and Perpendicular Lines

Activities: Parallel Lines in the Coordinate Plane Discussion Questions

Study Aids: Lines in the Coordinate Plane

Practice: Parallel Lines in the Coordinate Plane

Real World: Parallel Lines In The Coordiante Plane